Full Text (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

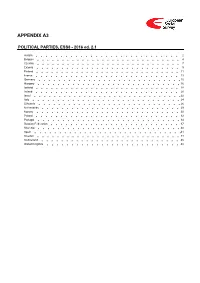

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

7. Political Development and Change

F. Yaprak Gursoy 1 Democracy and Dictatorship in Greece Research Question: From its independence in 1821 until 1974 democracy in Greece witnessed several different types of military interventions. In 1909, the military initiated a short-coup and quickly returned to its barracks, allowing democracy to function until the 1920s. During the 1920s, the armed forces intervened in politics frequently, without establishing any form of dictatorship. This trend has changed in 1936, when the Greek military set up an authoritarian regime that lasted until the Second World War. In 1967, again, the Generals established a dictatorship, only to be replaced by democracy in 1974. Since then, the Armed Forces in Greece do not intervene in politics, permitting democracy to be consolidated. What explains the different behaviors of the military in Greece and the consequent regime types? This is the central puzzle this paper will try to solve. Studying Greece is important for several reasons. First, this case highlights an often understudied phenomenon, namely military behavior. Second, analyzing Greece longitudinally is critical: military behavior varied within the country in time. What explains the divergent actions of the same institution in the same polity? Looking at Greece’s wider history will allow showing how the same coalitional partners and how continuous economic growth led to different outcomes in different circumstances and what those different circumstances were. Finally, studying the divergent behavior of the Greek military helps to understand democratic consolidation in this country. Even though Greece has a record of military interventions and unstable democracies, since 1974, it is considered to have a consolidated democracy. -

The Decline of the Military's Political Influence in Turkey

The decline of the military’s political influence in Turkey By Anwaar Mohammed A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Philosophy Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham August 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The political role of Turkey’s military has been declining with the strengthening of the civilian institutions and the introduction of new political factors. Turkey’s political atmosphere has changed towards civilian control of the military. The research focuses on analysing the various political factors and their impact on the political role of the military. The military’s loss of political influence in handling political challenges will be assessed against the effectiveness of the military’s political ideology. The shift in civil-military relations will be detected through the AKP’s successful political economy and popular mandate. The EU as an external factor in dismantling the military’s political prerogatives will be assessed. Greece’s route toward democratization of its civil-military relations compared to Turkey. -

Expressions of Euroscepticism in Political Parties of Greece Eimantas K* Master’S in Political Science, Kaunas, Lithuania

al Science tic & li P Eimantas, J Pol Sci Pub Aff 2016, 4:2 o u P b f l i o c DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000202 l A a Journal of Political Sciences & f n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Public Affairs Research Article Open Access Expressions of Euroscepticism in Political Parties of Greece Eimantas K* Master’s in Political Science, Kaunas, Lithuania Abstract Eimantas Kocanas ‘Euroscepticism in political parties of Greece’, Master’s Thesis. Paper supervisor Prof. Doc. Mindaugas Jurkynas, Kaunas Vytautas Magnus University, Department of Diplomacy and Political Sciences. Faculty of Political Sciences. Euroscepticism (anti-EUism) had become a subject of analysis in contemporary European studies due to its effect on governments, parties and nations. With Greece being one of the nations in the center of attention on effects of Euroscepticism, it’s imperative to constantly analyze and research the Eurosceptic elements residing within the political elements of this nation. Analyzing Eurosceptic elements within Greek political parties, the goal is to: detect, analyze and evaluate the expressions of Euroscepticism in political parties of Greece. To achieve this: 1). Conceptualization of Euroscepticism is described; 2). Methods of its detection and measurement are described; 3). Methods of Euroscepticism analysis are applied to political parties of Greece in order to conclude what type and expressions of Eurosceptic behavior are present. To achieve the goal presented in this paper, political literature, on the subject of Euroscepticism: 1). Perception of European integration; 2) Measurement of Euroscepticism; 3). Source of eurosceptic behavior; 4). Application of Euroscepticism; is presented in order to compile a method of analysis to be applied to current active Greek political parties in a duration of 2014-2015 period. -

A Decade of Crisis in the European Union: Lessons from Greece

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Katsanidou, Alexia; Lefkofridi, Zoe Article — Published Version A Decade of Crisis in the European Union: Lessons from Greece JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies Provided in Cooperation with: John Wiley & Sons Suggested Citation: Katsanidou, Alexia; Lefkofridi, Zoe (2020) : A Decade of Crisis in the European Union: Lessons from Greece, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, ISSN 1468-5965, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, Vol. 58, pp. 160-172, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13070 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/230239 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ www.econstor.eu JCMS 2020 Volume 58. -

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2019 Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann. 2021. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2019. Zurich: Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich. These (former) assistants have made major contributions to the dataset, without which CPDS would not exist. In chronological and descending order: Angela Odermatt, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, Sarah Engler, David Weisstanner, Panajotis Potolidis, Marlène Gerber, Philipp Leimgruber, Michelle Beyeler, and Sarah Menegal. -

Investing in the Roots of Your Political Ancestors

This is a repository copy of Investing in the roots of your political ancestors. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/174651/ Version: Published Version Monograph: Kammas, P., Poulima, M. and Sarantides, V. orcid.org/0000-0001-9096-4505 (2021) Investing in the roots of your political ancestors. Working Paper. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series, 2021004 (2021004). Department of Economics, University of Sheffield , Sheffield. ISSN 1749-8368 © 2021 The Author(s). For reuse permissions, please contact the Author(s). Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Department Of Economics Investing in the roots of your political ancestors Pantelis Kammas, Maria Poulima and Vassilis Sarantides Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series SERPS no. 2021004 ISSN 1749-8368 April 2021 Investing in the roots of your political ancestors Pantelis Kammasa, Maria Poulimab and Vassilis Sarantidesc a Athens University of Economics and Business, Patission 76, Athens 10434, Greece. -

The Territorial Politics of Welfare

The Territorial Politics of Welfare Nicola McEwen and Luis Moreno (eds.) Contents Chapter 1 Luis Moreno and Nicola McEwen: Exploring the Territorial Politics of Welfare Chapter 2 Nicola McEwen and Richard Parry: Devolution and the Preservation of the British Welfare State Chapter 3 Jörg Mathias: Welfare Management in the German Federal System: the Emergence of Welfare Regions? Chapter 4 Alistair Cole: Territorial Politics and Welfare Development in France Chapter 5 Raquel Gallego, Ricard Gomà and Joan Subirats: Spain, From State Welfare to Regional Welfare? Chapter 6 Valeria Fargion: From the Southern to the Northern Question. Territorial and Social Politics in Italy Chapter 7 Pierre Baudewyns and Régis Dandoy: The Preservation of Social Security as a National Function in the Belgian Federal State Chapter 8 Kaisa Lähteenmäki-Smith: Changing Political Contexts in the Nordic Welfare States. The central-local relationship in the 1990s and beyond Chapter 9 Daniel Béland and André Lecours: Nationalism and Social Policy in Canada and Quebec Chapter 10 Steffen Mau: European Social Policies and National Welfare Constituencies: Issues of Legitimacy and Public Support Chapter 11 Maurizio Ferrera: European Integration and Social Citizenship. Changing Boundaries, New Structuring? PREFACE Writing in 1979, Robert Pinker expressed dismay at the lack of analysis within the social sciences literature of the ‘...positive links between social policy and the recovery of a sense of national purpose’ (1979: 29). It is only now, over two decades later, that literature is beginning to emerge to explore the ways in which the welfare state informs, and is informed by, territorial identity and the politics of regionalism. -

Politics and Education

1 POLITICS AND EDUCATION: THE DEMOCRATISATION OF THE GREEK EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM by Apostolos Markopoulos Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 1986 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ABBREVIATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 CHAPTER I DEMOCRACY AND EDUCATION 8 CHAPTER II GREEK EDUCATION 1828-1949 17 Section 1 Greek Education 1828-1832 17 Section 2 Greek Education 1832-1862 18 Section 3 Greek Education 1863-1909 26 Section 4 Greek Education 1910-1935 29 Section 5 Greek Education 1936-1940 40 Section 6 Greek Education 1941-1943 41 Section 7 Greek Education 1944-1949 44 Section 8 Summary 48 CHAPTER III EDUCATION AND STABILITY 50 Section 1 The Liberal Parties in Power (1950-1952) 50 Section 2 The Conservative Party in Power (1953-1963) 53 Section 3 The Ideology and Programmes of the Political Parties 59 Section 4 Politics in Education 63 Section 5 Summary 95 CHAPTER IV THE LIGHT OF RENAISSANCE: THE REFORM OF 1964 97 Section 1 Introduction 97 Section 2 The Socio-econirnic Situation in Greek Society 97 Section 3 Political Conflicts: The Liberal Party in Power 100 Section 4 Debates Outside Parliament on the Educationan Reform of 1964 103 Section 5 Debates Inside Parliament on the Educationan Reform of 1964 110 Section 6 The Education Act of 1964 113 Section 7 Description of the Educational System after the Reforms of 1964 114 Section 8 Responses to the Implementation of the Reform 116 Section 9 Evaluation of the 1964 Reform 123 CHAPTER V EDUCATION ON A BACKWARD COURSE: THE PERIOD -

SYRIZA's Electoral Rise in Greece

Tsakatika, M. (2016) SYRIZA’S electoral rise in Greece: protest, trust and the art of political manipulation. South European Society and Politics, (doi:10.1080/13608746.2016.1239671) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/128645/ Deposited on: 20 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk33640 SYRIZA’s electoral rise in Greece: protest, trust and the art of political manipulation Abstract Between 2010 and 2015, a period of significant political change in Greece, the Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA), a minor party, achieved and consolidated major party status. This article explores the role of political strategy in SYRIZA’s electoral success. It argues that contrary to accepted wisdom, targeting a ‘niche’ constituency or protesting against the establishment will not suffice for a minor party to make an electoral breakthrough. SYRIZA’s case demonstrates that unless a minor party is ready to claim that it is willing and able to take on government responsibility, electoral advancement will not be forthcoming. The success of SYRIZA’s strategy can be attributed to favourable electoral demand factors and apt heresthetic manipulation of issue dimensions. Keywords: SYRIZA, Tsipras, Memorandum, minor parties, radical left, Greek party system, heresthetics Word count: 11,947 From a party lifespan perspective (Pedersen 1982), over the course of the last half century a swathe of minor parties have managed to cross both the threshold of representation and that of relevance, meaning that they have become parties with an established presence in legislative politics as well as parties with coalition potential or ‘blackmail’ potential if in opposition (Sartori 1976). -

Populism in the Baltic States a Research Report

Tallinn University Institute of Political Science and Governance / Open Estonia Foundation Populism in the Baltic States A Research Report Mari-Liis Jakobson, Ilze Balcere, Oudekki Loone, Anu Nurk, Tõnis Saarts, Rasa Zakeviciute November, 2012 “Populism in the Baltic States” is a research project funded by Open Estonia Foundation and conducted by Tallinn University Institute of Political Science and Governance, and partners. Research team: Project coordinator: Mari-Liis Jakobson Local research assistants: Ilze Balcere, University of Latvia Anu Nurk, Merilin Kreem, Miko Nukka, University of Tallinn Rasa Zakeviciute, University of Jyväskylä Advisory board: Leif Kalev, Oudekki Loone, Jane Matt, Tõnis Saarts, Peeter Selg 2 POPULISM IN BALTIC STATES: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project “Populism in the Baltic States” is a small-scale research project which aims to give an overview of the populist dimension of politics in the Baltic States and the successfulness of this political strategy, based on the experience from the previous general elections and social media. Theoretical background Even if widely used, populism is a very contested concept in political science, with rather vague meaning, “populist” sign could be attached on almost anything. This study and analytical elaborateness is based on Edward Shils’ classical definition, according to which populism means the supremacy of the will of the people and the direct relationship between the people and the government. More widely, we claim populism to be a “action/thought that puts people in the center of political life”. For conceptualisation sometimes more narrow explanation is used, seeing populist politics as political action or thought that is responding to elite/people cleavage. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions.