The Frontier in the Imperial Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Analyzing Mythical Characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh

WALIA journal 31(S4): 121-125, 2015 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2015 WALIA Compare and analyzing mythical characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh Mohammadtaghi Fazeli 1, Behrooze Varnasery 2, * 1Department of Archaeology, Shushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shushtar, Iran 2Department of Persian literature Shoushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shoushtar Iran Abstract: The content difference in both works are seen in rhetorical Science, the unity of epic tone ,trait, behavior and deeds of heroes and Kings ,patriotism in accordance with moralities and their different infer from epic and mythology . Their similarities can be seen in love for king, obeying king, theology, pray and the heroes vigorous and physical power. Comparing these two works we concluded that epic and mythology is more natural in the Epic of the king than Garshaseb Nameh. The reason that Ferdowsi illustrates epic and mythological characters more natural and tangible is that their history is important for him while Garshaseb Nameh looks on the surface and outer part of epic and mythology. Key words: The epic of the king;.Epic; Mythology; Kings; Heroes 1. Introduction Sassanid king Yazdgerd who died years after Iran was occupied by muslims. It divides these kings into *Ferdowsi has bond thought, wisdom and culture four dynasties Pishdadian, Kayanids, Parthian and of ancient Iranian to the pre-Islam literature. sassanid.The first dynasties especially the first one Garshaseb Nameh has undoubtedly the most shares have root in myth but the last one has its roots in in introducing mythical and epic characters. This history (Ilgadavidshen, 1999) ballad reflexes the ethical and behavioral, trait, for 4) Asadi Tusi: The Persian literature history some of the kings and Garshaseb the hero. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales by Aali Mirjat B.A., (Hons., History), Lahore University of Management Sciences, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Aali Mirjat 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Aali Mirjat Degree: Master of Arts Title: Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales Examining Committee: Chair: Evdoxios Doxiadis Assistant Professor Luke Clossey Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Bidisha Ray Co-Supervisor Senior Lecturer Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor Tara Mayer External Examiner Instructor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: July 16, 2018 ii Abstract This thesis examines Sindhi Sufi folktales as retold by five “modern” individuals: the nineteenth- century British explorer Richard Burton and four Sindhi intellectuals who lived and wrote in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Lilaram Lalwani, M. M. Gidvani, Shaikh Ayaz, and Nabi Bakhsh Khan Baloch). For each set of retellings, our purpose will be to determine the epistemological and emotional sympathy the re-teller exhibits for the plot, characters, sentiments, and ideas present in the folktales. This approach, it is hoped, will provide us a glimpse inside the minds of the individual re-tellers and allow us to observe some of the ways in which the exigencies of a secular western modernity had an impact, if any, on the choices they made as they retold Sindhi Sufi folktales. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

List of Stations

Sr # Code Division Name of Retail Outlet Site Category City / District / Area Address 1 101535 Karachi AHMED SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI EAST DADABHOY NOROJI ROAD AKASHMIR ROAD 2 101536 Karachi CHAND SUPER SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI WEST PSO RETAIL DEALERSST/1-A BLOCK 17F 3 101537 Karachi GLOBAL PETROLEUM SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI EAST PLOT NO. 234SECTOR NO.3, 4 101538 Karachi FAISAL SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI WEST ST 1-A BLOCK 6FEDERAL B AREADISTT K 5 101540 Karachi RAANA GASOLINE N/V CF KARACHI WEST SERVICE STATIONPSO RETAIL DEALERAPWA SCHOOL LIAQA 6 101543 Karachi SHAHGHAZI P/S N/V DFA MALIR SURVEY#81,45/ 46 KM SUPER HIGHWAY 7 101544 Karachi GARDEN PETROL SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI SOUTH OPP FATIMA JINNAHGIRLS HIGH SCHOOLN 8 101545 Karachi RAZA PETROL SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI SOUTH 282/2 LAWRENCE ROADKARACHIDISTT KARACHI-SOUTH 9 101548 Karachi FANCY SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI WEST ST-1A BLOCK 10FEDERAL B AREADISTT KARACHI WEST 10 101550 Karachi SIDDIQI SERVIC STATION S/S DFB KARACHI EAST RASHID MINHAS ROADKARACHIDISTT KARACHI EAST 11 101555 Karachi EASTERN SERIVCE STN N/V DFA KARACHI WEST D-201 SITEDIST KARACHI-WEST 12 101562 Karachi AL-YASIN FILL STN N/V DFA KARACHI WEST ST-1/2 15-A/1 NORTHKAR TOWNSHIP KAR WEST 13 101563 Karachi DUREJI FILLING STATION S/S DFA LASBELA KM-4/5 HUB-DUREJI RDPATHRO HUBLASBE 14 101566 Karachi R C D FILLING STATION N/V DFA LASBELA HUB CHOWKI LASBELADISTT LASBELA 15 101573 Karachi FAROOQ SERVICE CENTRE N/V CF KARACHI WEST N SIDDIQ ALI KHAN ROADCHOWRANGI NO-3NAZIMABADDISTT 16 101577 Karachi METRO SERVICE STATION -

Ca' Foscari and Pakistan Thirty Years of Archaeological Surveys And

150 Years of Oriental Studies at Ca’ Foscari edited by Laura De Giorgi and Federico Greselin Ca’ Foscari and Pakistan Thirty Years of Archaeological Surveys and Excavations in Sindh and Las Bela (Balochistan) Paolo Biagi (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Abstract This paper regards the research carried out by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Sindh and Las Bela province of Balochistan (Pakistan). Until the mid ’80s the prehistory of the two regions was known mainly from the impressive urban remains of the Bronze Age Indus Civilisation and the Pal- aeolithic assemblages discovered at the top of the limestone terraces that estend south of Rohri in Up- per Sindh. Very little was known of other periods, their radiocarbon chronology, and the Arabian Sea coastal zone. Our knowledge radically changed thanks to the discoveries made during the last three decades by the Italian Archaeological Mission. Thanks to the results achieved in these years, the key role played by the north-western regions of the Indian Subcontinent in prehistory greatly improved. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Archaeological Results. – 3 Discussion. – 3.1 The Chert Outcrops. – 3.2 The Late (Upper) Palaeolithic and Mesolithic sites. – 3.3 The Shell Middens of Las Bela Coast. – 3.4 The Indus Delta Country. – 4 Conclusion. Keywords Sindh. Las Bela. Indus delta. Prehistoric sites. Radiocarbon chronology. 1 Introduction Due to its location midway between the Iranian uplands, in the west, and the Thar or Great Indian Desert, in the east, the Indus Valley and Sindh have always played a unique role in the prehistory of south Asia, and the Indian Subcontinent in particular. -

Shahnameh) and Balder (Scandinavian Epic)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Revista Amazonia Investiga Florencia, Colombia, Vol. 6 Núm. 10 /enero-junio 2017/ 151 Artículo de investigación Interpretation and analysis of epic thinking in Iran and Scandinavia emphasizing the story of Esfandiar (Shahnameh) and Balder (Scandinavian epic) Interpretación y análisis del pensamiento épico en Irán y Escandinavia enfatizando la historia de Esfandiar (Shahnameh) y Balder (épica escandinava) Interpretação e análise do pensamento épico no Irã e na Escandinávia enfatizando a história de Esfandiar (Shahnameh) e Balder (épico escandinavo) Recibido: 9 de abril de 2017. Aceptado: 30 de mayo de 2017 Escrito por: Shahrbanoo Ganjeh39 Alimohammad Moazzeni2* Tofigh Sobhani3 Mohammed Reza Shad Manamen4 Abstract Resumen Apart from the impact and impact of the two Además del impacto y el impacto de las dos lands, a way can be opened in There is a special tierras, se puede abrir una vía en Hay un tema subject that there is a shared point of content in especial en el que hay un punto de contenido it and it is a source of analogy A topic, a tendency compartido y es una fuente de analogía Un tema, and a special content of common interest in two una tendencia y un contenido especial de común different territories. Question one of the most interés en dos territorios diferentes. Pregunta important and frequent points in the history of uno de los puntos más importantes y frecuentes the literatures and beliefs of different lands It is en la historia de las literaturas y creencias de on the side of history and on the side of human diferentes países. -

Report on the Administration of the Local Boards in the Bombay

1 Reports on the Administration of the Local ~oards in the Bombay Presidency including :sind ior the year 1932--33. GOVERNMENT OF BOl\IBAY. GENERAL DEPARTMENT. · ' · Resolution No. P. 52. \..__ Bombay Castle, 4th April 1934. Read reportS. from the Commissioner in Sind, the Commissioners, Northern Division, -Central Division and Southern Division, on the adminiRtration of Local Boards in their -respective charges during the year 1932--33. · REsoLUTION.-Number of Local Boarils.--The number of Local Boards remained the same. · · _ - 2. ·Area and p:>pulation.-The increase or decrease in the figlires of population of Local Boards in Sind as compared with those of the preceding year is due to rectification of errors by reference to the census report of 1931. 3: Oonstitutwn.-The constitution of the Local Boards remained unchanged. 4. Electwns.-In the Central and Northern Divisions no triennial elections were held during the year under report. The general electionS of all the Boards in Sind and in the Southern Division were held during this year with the results shown in Appendix A.* Interest in the elections varied from district to district and from taluka to ~luka. In some places elections were very keenly contested, while in others they excited little public interest. · In Sind the number of con stituencies which were uncontested was large in proportion to the total number _of seats. Of 156 constituencies in .eight District· Boards in only 49 were there contests. -' 5. Meetings.-The Taluka Local Boatds of Shahdadpur, Sinjhoro and Moro in Sind, Igatpuri and Man in the Central Division, Dahanu and Murbad in the Northern Division and Dharwar, Karajgi, Shiggaon and Gadag in Southern Division, failed to comply with the provisions of section 35 (1) of the Bombay Local Boards Act, 1923, as they did not hold the requisite nUll\ber of quarterly general' meetings. -

Educación, Política Y Valores

1 Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores. Http://www.dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/ Año: VII Número: 2 Artículo no.:119 Período: 1ro de enero al 30 de abril del 2020. TÍTULO: Un análisis empírico de la cerámica esmaltada del sitio de Mansurah. AUTORES: 1. Assist. Prof. Muhammad Hanif Laghari. 2. Dr. Mastoor Fatima Bukhari. RESUMEN: Mansurah fue la primera ciudad árabe establecida en el subcontinente indio entre 712–1025 dC por el gobernador omeya Amr Thaqafi Construido en el Shahdadpur del distrito de Sanghar, Sindh. Durante este período, los gobernantes árabes extendieron el comercio nacional e internacional desde Sindh. La espectroscopia fue utilizada para examinar el material de cultivo excavado y para encontrar el origen de la cerámica esmaltada. Las evidencias empíricas extraídas del material cultural resaltan la composición de la pasta de color utilizada en estos vasos rotos y se preparan utilizando la arena de dos tipos diferentes de rocas como la volcánica y la metamórfica. Este estudio resalta las relaciones árabe-sindh y otros aspectos culturales de esta fase específica de la historia de Sindh, Pakistán. PALABRAS CLAVES: Arqueología, Historia, Geografía, cerámica esmaltada, relación y comercio. TITLE: An empirical analysis of glazed pottery from the site of Mansurah. 2 AUTHORS: 1. Assist. Prof. Muhammad Hanif Laghari. 2. Dr. Mastoor Fatima Bukhari. ABSTRACT: Mansurah was the first Arab city established in the Indian sub-continent between 712–1025 AD by the Umayyad governor ‘Amr Thaqafi Built in the Shahdadpur of District Sanghar, Sindh. During this period, the Arab rulers extended national and international trade from Sindh. The spectroscopy was used to examine the excavated culture material and to find the origin of the glazed pottery. -

Did-Islam-Spread-By-The-Sword -A

2 | Did Islam Spread by the Sword? A Critical Look at Forced Conversions Author Biography Hassam Munir lives in Toronto, Canada, and has a BA in History and Communication Studies (2017). He has experience in the fields of public history and journalism, and was recognized as an Emerging Historian at the 2017 Heritage Toronto Awards. Hassam is currently considering an offer of admission to the MA program in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern History at the University of Toronto. Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2018. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Did Islam Spread by the Sword? A Critical Look at Forced Conversions Abstract The question of forced conversions to Islam in history is a cornerstone of the centuries-old “spread-by-the-sword” narrative that has been (and continues to be) used to demonize Islam and Muslims. However, many leading present-day historians have challenged this narrative. They recognize that there have been cases of forced conversion, but also that these were rare, exceptional, occurred in particular contexts, and in violation of the Qur’anic prohibition of this practice. This article provides a cursory perusal of some of the arguments that have been used to discredit this narrative and examines three cases of forced conversion to Islam in history: the spread of Islam in South Asia, the Ottomans’ devshirme system, and Imam Yahya’s “Orphans’ Decree” in Yemen. -

In Yohanan Friedmann (Ed.), Islam in Asia, Vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1984), P

Notes INTRODUCTION: AFGHANISTAN’S ISLAM 1. Cited in C. Edmund Bosworth, “The Coming of Islam to Afghanistan,” in Yohanan Friedmann (ed.), Islam in Asia, vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1984), p. 13. 2. Erica C. D. Hunter, “The Church of the East in Central Asia,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 78 (1996), pp. 129–42. On Herat, see pp. 131–34. 3. On Afghanistan’s Jews, see the discussion and sources later in this chapter and notes 163 to 169. 4. Bosworth (1984; above, note 1), pp. 1–22; idem, “The Appearance and Establishment of Islam in Afghanistan,” in Étienne de la Vaissière (ed.), Islamisation de l’Asie Centrale: Processus locaux d’acculturation du VIIe au XIe siècle, Cahiers de Studia Iranica 39 (Paris: Association pour l’Avancement des Études Iraniennes, 2008); and Gianroberto Scarcia, “Sull’ultima ‘islamizzazione’ di Bāmiyān,” Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli, new series, 16 (1966), pp. 279–81. On the early Arabic sources on Balkh, see Paul Schwarz, “Bemerkungen zu den arabischen Nachrichten über Balkh,” in Jal Dastur Cursetji Pavry (ed.), Oriental Studies in Honour of Cursetji Erachji Pavry (London: Oxford Univer- sity Press, 1933). 5. Hugh Kennedy and Arezou Azad, “The Coming of Islam to Balkh,” in Marie Legen- dre, Alain Delattre, and Petra Sijpesteijn (eds.), Authority and Control in the Countryside: Late Antiquity and Early Islam (London: Darwin Press, forthcoming). 6. For example, Geoffrey Khan (ed.), Arabic Documents from Early Islamic Khurasan (London: Nour Foundation/Azimuth Editions, 2007). 7. Richard W. Bulliet, Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quan- titative History (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979); Derryl Maclean, Re- ligion and Society in Arab Sind (Leiden: Brill, 1989); idem, “Ismailism, Conversion, and Syncretism in Arab Sind,” Bulletin of the Henry Martyn Institute of Islamic Studies 11 (1992), pp. -

Additional Catalogue Entries

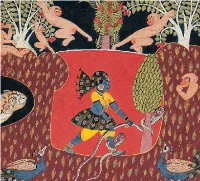

EPIC TALES from ANCIENT INDIA 1 2 EPIC TALES from ANCIENT INDIA 3 Note: need to add SDMA and Yale to title page This book is published in conjunction with the exhi- bition [Exhibition title], presented at [Museum] from [date] to [date]. Copyright © 2016 __________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, record- ing, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [please provide or L|M will apply] ISBN 978-0-300-22372-9 Published by The San Diego Museum of Art Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London 302 Temple Street P.O. Box 209040 New Haven, CT 06520-9040 yalebooks.com/art Produced by Lucia | Marquand, Seattle www.luciamarquand.com Edited by _______ Designed by Zach Hooker Typeset in Quadraat by Brynn Warriner Proofread by TK TK Color management by iocolor, Seattle Printed and bound in China by Artron Art Group 4 toc TK 5 Director’s Foreword The San Diego Museum of Art is blessed to have one of the great collections of Indian painting, the bequest of one of the great connoisseurs of our time, Edwin Binney 3rd. This collection of over 1,400 paintings has, over the years, provided material for a number of exhibitions that have examined the subject of Indian painting from many different angles, as only a collection of this breadth and depth can do. Our latest exhibition, Epic Tales from Ancient India, aims to approach the topic from yet another per- spective, by considering the paintings alongside the classics of literature that they illustrate.