Shakespeare and the Actor's Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Sydney Theatre Award Nominations

2015 SYDNEY THEATRE AWARD NOMINATIONS MAINSTAGE BEST MAINSTAGE PRODUCTION Endgame (Sydney Theatre Company) Ivanov (Belvoir) The Present (Sydney Theatre Company) Suddenly Last Summer (Sydney Theatre Company) The Wizard of Oz (Belvoir) BEST DIRECTION Eamon Flack (Ivanov) Andrew Upton (Endgame) Kip Williams (Love and Information) Kip Williams (Suddenly Last Summer) BEST ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE Paula Arundell (The Bleeding Tree) Cate Blanchett (The Present) Jacqueline McKenzie (Orlando) Eryn Jean Norvill (Suddenly Last Summer) BEST ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE Colin Friels (Mortido) Ewen Leslie (Ivanov) Josh McConville (Hamlet) Hugo Weaving (Endgame) BEST ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Blazey Best (Ivanov) Jacqueline McKenzie (The Present) Susan Prior (The Present) Helen Thomson (Ivanov) BEST ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Matthew Backer (The Tempest) John Bell (Ivanov) John Howard (Ivanov) Barry Otto (Seventeen) BEST STAGE DESIGN Alice Babidge (Suddenly Last Summer) Marg Horwell (La Traviata) Renée Mulder (The Bleeding Tree) Nick Schlieper (Endgame) BEST COSTUME DESIGN Alice Babidge (Mother Courage and her Children) Alice Babidge (Suddenly Last Summer) Alicia Clements (After Dinner) Marg Horwell (La Traviata) BEST LIGHTING DESIGN Paul Jackson (Love and Information) Nick Schlieper (Endgame) Nick Schlieper (King Lear) Emma Valente (The Wizard of Oz) BEST SCORE OR SOUND DESIGN Stefan Gregory (Suddenly Last Summer) Max Lyandvert (Endgame) Max Lyandvert (The Wizard of Oz) The Sweats (Love and Information) INDEPENDENT BEST INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION Cock (Red -

Comedy, Tragedy, Life: an Interview with Nadia Tass and David Parker

FINN (KODI SMIT-MCPHEE) AND JACK (TOM RUSSELL) IN MATCHING JACK AN INTERVIEW WITH NADIA TASS AND DAVID PARKER TASS AND PARKER'S LATEST FILM, MATCHING JACK. SKILFULLY MINES three years ago, we were in Film Finance THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE. BRIAN MCFARLANE TALKS TO THE PAIR Corporation being assessed for this film ABOUT THE FILM, AS WELL AS DELVING INTO THE INTRICACIES OF SOME we've just done. Matching Jack. The two OF THE FILMMAKERS' EARLIER WORK. people considering this film at that time did not assess it accurately. One of them said, 'The father needs to be a nicer person.' Now, BRIAN MCFARLANE: You've been making we prefer to be going down the feature film I don't know where that person's judgement films together regularly for twenty-five route, but it's terrific when, say, Disney or was coming from and why he was sitting in years now. How difficult has it been to Warner Bros, come to Nadia saying, 'We'd that chair. His opinion was completely wrong: maintain a career like that in Australia? like you to direct this or that piece.' if we'd followed his suggestion we'd have NADIA TASS: Oh, impossible. It's the tough- NT: It's the material, too. I'd much rather do had no film. The woman assessing it also est thing. That's why we work overseas so a really good high-end television story than wanted the female lead to be a battered wife. much. We've made both features and televi- some crappy feature. -

Sugar Babies - the Quintessential Burlesque Show

SEPTEMBER,1986 Vol 10 No 8 ISSN 0314 - 0598 A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Sugar Babies - The Quintessential Burlesque Show personality and his own jokes. Not all the companies, however, lived up to the audience's expectations; the comedians were not always brilliant and witty, the girls weren't always beautiful. This proved to be Ralph Allen's inspiration for SUGAR BABIES. "During the course of my research, one question kept recurring. Why not create a quintessen tial Burlesque Show out of authentic materials - a show of shows as I have played it so often in the theatre of my mind? After all, in a theatre of the mind, nothing ever disappoints. " After running for seven years in America - both in New York and on tour - the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust will mount SUGAR BABIES in Australia, opening in Sydney at Her Majesty's Theatre on October 30. In February it will move to Melbourne and other cities, including Adelaide, Perth and Auckland. The tour is expected to last about 39 weeks. Eddie Bracken, who is coming from the USA to star in the role of 1st comic in SUGAR BABIES, received rave reviews from critics in the USA. "Bracken, with his rolling eyes, rubber face and delightful slow burns, is the consummate performer, " said Jim Arpy in the Quad City Times. Since his debut in 1931 on Broadway, Bracken has appeared in Sugar Babies from the original New York production countless movies and stage shows. Garry McDonald will bring back to life one of Harry Rigby, happened to be at the con Australia's greatest comics by playing his SUGAR BABIES, conceived by role as "Mo" (Roy Rene). -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture. -

LESLEY VANDERWALT Make-Up and Hair Designer

LESLEY VANDERWALT Make-Up And Hair Designer FILM PROMETHEUS 2 Make-Up and Hair Designer Filming Begins April 2016 Director: Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox GODS OF EGYPT Make-Up and Hair Designer Summit Entertainment Director: Alex Proyas MAD MAX: FURY ROAD Make-Up and Hair Designer Village Roadshow Pictures Director: George Miller Winner: Academy Award for Best Make-Up and Hairstyling Winner: BAFTA for Best Make-up and Hair Winner: Critics’ Choice Award for Best Hair & Make-Up Winner: Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild Awards for Best Period and/or Character Make-Up THE GREAT GATSBY Make-Up and Hair Supervisor – Additional Design Warner Bros. Director: Baz Luhrmann Winner of the M.A.C Austrailia APDG Award for Make-up shared with Kerry Warn and Maritzio Silvi. Nominated for Hollywood Make-up Artists and Hairstylists Guild Award Best Character Make-Up SLEEPING BEAUTY Make-Up and Hair Designer / Make-Up Department Head Magic Films Director: Julia Leigh Cast: Emily Browning, Rachael Blake, Ewen Leslie, Eden Falk, Mirrah Folks, Chris Haywood, Hugh Keays-Byrne, Tammy Macintosh, Tracy Mann, Sarah Snook, Matthew Whittet Winner of the M.A.C Austrailia APDG Award for Make-up KNOWING Make-Up and Hair Designer Summit Entertainment Director: Alex Proyas Cast: Rose Byrne, Ben Mendelsohn AUSTRAILIA Make-Up and Hair Supervisor – Additional Design 20th Century Fox Director: Baz Lurmann Cast: Jack Thompson, Ben Mendelsohn, Jacek Koman, Sandy Gore, Wah Yuen, Ursula Yovich, GHOST RIDER Make-Up and Hair Designer Columbia Pictures Director: Mark Stephan -

© 2018 Mystery Road Media Pty Ltd, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Create NSW, Screenwest (Australia) Ltd, Screen Australia

© 2018 Mystery Road Media Pty Ltd, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Create NSW, Screenwest (Australia) Ltd, Screen Australia SUNDAYS AT 8.30PM FROM JUNE 3, OR BINGE FULL SEASON ON IVIEW Hotly anticipated six-part drama Mystery Road will debut on ABC & ABC iview on Sunday, 3 June at 830pm. Because just one episode will leave audiences wanting for more, the ABC is kicking off its premiere with a special back-to-back screening of both episodes one and two, with the entire series available to binge on iview following the broadcast. Contact: Safia van der Zwan, ABC Publicist, 0283333846 & [email protected] ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Filmed in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, Aaron Pedersen and Judy Davis star in Mystery Road – The Series a six part spin-off from Ivan Sen’s internationally acclaimed and award winning feature films Mystery Road and Goldstone. Joining Pedersen and Davis is a stellar ensemble casting including Deborah Mailman, Wayne Blair, Anthony Hayes, Ernie Dingo, John Waters, Madeleine Madden, Kris McQuade, Meyne Wyatt, Tasia Zalar and Ningali Lawford-Wolf. Directed by Rachel Perkins, produced by David Jowsey & Greer Simpkin, Mystery Road was script produced by Michaeley O’Brien, and written by Michaeley O’Brien, Steven McGregor, Kodie Bedford & Tim Lee, with Ivan Sen & the ABC’s Sally Riley as Executive Producers. Bunya Productions’ Greer Simpkin said: “It was a great honour to work with our exceptional cast and accomplished director Rachel Perkins on the Mystery Road series. Our hope is that the series will not only be an entertaining and compelling mystery, but will also say something about the Australian identity.” ABC TV Head of Scripted Sally Riley said: “The ABC is thrilled to have the immense talents of the extraordinary Judy Davis and Aaron Pedersen in this brand new series of the iconic Australian film Mystery Road. -

Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections

University of Wollongong Research Online Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections 11-1977 Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Robert Page Editor Lucy Wagner Editor Bruce Knappett Associate Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia Recommended Citation Page, Robert; Wagner, Lucy; and Knappett, Bruce, (1977), Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977, Theatre Publications Ltd., New Lambton Heights, 66p. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia/14 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Description Contents: Departments 2 Comments 4 Quotes and Queries 5 Letters 6 Whispers, Rumours and Facts 62 Guide, Theatre, Opera, Dance 3 Spotlight Peter Hemmings Features 7 Tracks and Ways - Robin Ramsay talks to Theatre Australia 16 The Edgleys: A Theatre Family Raymond Stanley 22 Sydney’s Theatre - the Theatre Royal Ross Thorne 14 The Role of the Critic - Frances Kelly and Robert Page Playscript 41 Jack by Jim O’Neill Studyguide 10 Louis Esson Jess Wilkins Regional Theatre 12 The Armidale Experience Ray Omodei and Diana Sharpe Opera 53 Sydney Comes Second best David Gyger 18 The Two Macbeths David Gyger Ballet 58 Two Conservative Managements William Shoubridge Theatre Reviews 25 Western Australia King Edward the Second Long Day’s Journey into Night Of Mice and Men 28 South Australia Annie Get Your Gun HMS Pinafore City Sugar 31 A.C.T. -

STC Macbeth's.Idml

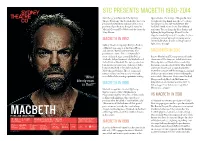

STC PRESENTS MACBETH 1980-2014 Over the 34-year-history of the Sydney Opera House. The design of the production Theatre Company “the Scottish play” has been brought the play fi rmly into the 20th century produced seven times, making it STC’s most by taking on a desolate World War I-like performed production, alongside Away by battlefi eld with actors dressed in military Michael Gow and Two Weeks with the Queen by uniforms. The set design by John Gunter and Mary Morris. lighting by Nigel Levings allowed for the stage to seamlessly morph from place to place creating a sinister atmosphere using arrow MACBETH IN 1982 slits in walls where shards and fragments of light shone through. Sydney Theatre Company’s fi rst production of Macbeth was staged at the Opera House and directed by Richard Wherrett. The MACHOMER IN 2010 performance starred three of Australia’s most celebrated stage actors, John Bell as In 2010 Macbeth at STC was performed by the Macbeth, Robyn Nevin as Lady Macbeth and characters of The Simpsons, titled MacHomer. Colin Friels as Macduff. The 1982 production This adaptation of Macbeth was created by had directorial references of character links Canadian comedian Rick Miller who in his between Macbeth and Hamlet and Lady one man show took on 50 characters Macbeth and Ophelia. The set design had from the cartoon while wearing traditional terracotta hues and was a series of rough, Shakespearean costume and mimicking the “What monolithic slabs creating a primitive setting. voices of the characters. Homer was Macbeth, bloody man Marge was Lady Macbeth, Mr Burns was MACBETH IN 1996 King Duncan and Barney was Macduff. -

COLIN FRIELS | Actor

COLIN FRIELS | Actor FILM Year Production / Character Director Company 2013 THE TURNING Various Arenamedia Narrator. Segment “Ash Wednesday” 2011 THE EYE OF THE STORM Fred Schepisi The Eye of The Storm Productions Athol Shreve 2010 A HEARTBEAT AWAY Gale Edwards Heartbeat Productions Pty Ltd Mayor Riddick 2009 TOMORROW WHEN THE WAR Stuart Beattie Tomorrow When The War Began BEGAN Productions P/L Dr Clement 2009 MATCHING JACK Nadia Tass Love & Mortar Productions Professor Nelson 2007 THE INFORMANT Peter Andrikidis Screentime Doug Lamont 2007 THE NOTHING MEN Mark Fitzpatrick Alchemy Film Productions Pty Ltd Jack 2005 SOLO Morgan O’Neill Miramax/Project Greenlight Barrett 2005 THE BOOK OF REVELATION Ana Kokkinos Wildheart Zizani Pty Ltd Olsen 2003 THE ILLUSTRATED FAMILY Kriv Stenders POD IFD Pty Ltd DOCTOR Ray 2003 MAX’S DREAMING Sandra Sciberras Prod: Greg Parish Mark Bryce Shanahan Management Pty Ltd Level 3 | Berman House | 91 Campbell Street | Surry Hills NSW 2010 PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] 2003 TOM WHITE Alkinos Tsilimidos Rescued Films Tom 2003 NATALIE WOOD Peter Bogdanovich Cypress Point Productions Nick Gurdin 2001 BLACK & WHITE Craig Lahiff B&W Productions Father Tom Dixon 2001 THE MAN WHO SUED GOD Mark Joffe Gannon Films David Myers 1996 DARK CITY Alex Proyas Dark City Productions Det. Eddie Walenski 1995 MR RELIABLE Nadia Tass Hayes McElroy Productions Wally 1995 COSI Mark Joffe Smiley Films Errol 1994 BACK OF BEYOND -

Australian Cinema Umbrella Australian Cinema

20152017 UMBRELLAUMBRELLA CATALOGUECATALOGUE AUSTRALIAN CINEMA UMBRELLA AUSTRALIAN CINEMA DVD DVD DCP DVD BD THE ADVENTURES OF BARRY MCKENZIE ANGEL BABY AUTOLUMINESCENT Reviled by the critics! This year marks the 20th Anniversary of this Containing a selection of rare footage and moving interviews Adored by fair-dinkum Aussies! landmark Australian Drama. with Rowland S. Howard, Nick Cave, Wim Wenders, Mick Harvey, Lydia Lunch, Henry Rollins, Thurston Moore, In this fan-bloody-tastic classic, directed by Bruce Beresford Winner of 7 AFI Awards, including Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Actress. Bobby Gillespie, and Adalita, AUTOLUMINESCENT traces (his first feature) Australia’s favourite wild colonial boy, the life of Roland S. Howard, as words and images etch Barry McKenzie (Barry Crocker), journeys to the old country Written and directed by Michael Rymer (Hannibal) and light into what has always been ‘the mysterious dark’. accompanied by his Aunt Edna Everage (Barry Humphries) starring Jacqueline McKenzie (Romper Stomper), John to take a Captain Cook and further his cultural and intellectual Lynch (In the Name of the Father) and Colin Friels (Malcolm), “ IF YOU MAKE SOMETHING THAT IS SO MAGICAL, SO UNIQUE education. this multi-award winning drama tells a tragic tale of love YOU WILL PAY THE PRICE... IT’S THE DEVIL’S BARGAIN.” between two people with schizophrenia as they struggle with LYDIA LUNCH life without medication. “ HEARTBREAKINGLY GOOD AND FILLED WITH A DESPERATE INTENSITY.” JANET MASLIN, THE NEW YORK TIMES FOR ALL ENQUIRIES REGARDING UMBRELLA’S THEATRICAL CATALOGUE umbrellaent.films @Umbrella_Films PLEASE CONTACT ACHALA DATAR – [email protected] | 03 9020 5134 AUSTRALIAN CINEMA BP SUPER SHOW DVD LOUIS ARMSTRONG One of the greatest musical talents of all time, Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong raised his trumpet and delivered a sensational concert for the BP Supershow, recorded at Australia’s Television City (GTV 9 Studios) in 1964. -

Filthy Rich & Homeless MEDIA KIT 15.5.17

PRESS KIT PRODUCTION CONTACT Blackfella Films Darren Dale & Jacob Hickey Tel: +61 2 9380 4000 Email: [email protected] www.blackfellafilms.com.au FILTHY RICH & HOMELESS 1 © 2017 Screen Australia, Special Broadcasting Service Corporation and Blackfella Films Pty Ltd PRODUCTION NOTES Producer Darren Dale Series Producer & Writer Jacob Hickey Mark Dooley, Celeste Geer, David Grusovin, Robert Hayward, Location Directors Mariel Thomas Vaughn Dagnell, Craig Donaldson, Claire Leeman, Mike Shooter Directors Polson, Aaron Smith Production Company Blackfella Films Pty Ltd Genre Documentary Series Language English Aspect Ratio 16 x 9 Durations EP 1 00:53:41:08 EP 2 00:56:02:21 EP 3 00:49:31:08 Sound Stereo Canon EOS C300 MKII, Sony Alpha A75 II, Canon EOS C300 Shooting Gauges / Cameras MKI. ALEXA mini. LOGLINE Five wealthy Australians give up their lavish lifestyles for ten days to discover what life is like for the nation’s 105,000 homeless people. FILTHY RICH & HOMELESS 2 © 2017 Screen Australia, Special Broadcasting Service Corporation and Blackfella Films Pty Ltd SERIES SYNOPSIS There’s a crisis in Australia. More than 100,000 people have no place to call home. 1 And with house and rent prices rocketing - homelessness is a frightening possibility for more of us than ever before. 2 For five wealthy volunteers, it’s about to become a terrifying reality. They’ve all agreed to swap their lavish lifestyles for 10 days living on the streets of Melbourne. They’re going to find out what it’s like to go from having everything to having absolutely nothing. Preparing to live amongst Australia’s homeless are: Self-made millionaire Tim Guest, daughter of boxing champion Kayla Fenech, rags to riches beauty entrepreneur Jellaine Dee, third generation pub baron Stu Laundy and model & Sydney socialite Christian Wilkins. -

MEDIA KIT As at 22.8.16

Screen Australia and Seven Network present A Screentime Production MEDIA KIT As at 22.8.16 NETWORK PUBLICIST Elizabeth Johnson T 02 8777 7254 M 0412 659 052 E [email protected] ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Screen Australia and Seven Network present a Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production The Secret Daughter produced with the assistance of Screen Australia and Screen NSW. The major new drama for Channel Seven - THE SECRET DAUGHTER starring Jessica Mauboy, was filmed in Sydney and country NSW. The ARIA and AACTA award-winning singer and actress leads the cast as Billie Carter, a part- time country pub singer whose life changes forever after a chance meeting with wealthy city hotelier Jack Norton, played by acting great Colin Friels. Bonnie Sveen (Home and Away) plays Billie’s best friend Layla. The feel-good drama also stars Matt Levett (A Place To Call Home, Devil’s Playground), David Field (Catching Milat, No Activity), Rachel Gordon (Winter, The Moodys, Blue Heelers), Salvatore Coco (Catching Milat, The Principal), Jared Turner (The Almighty Johnsons, The Shannara Chronicles) and outstanding newcomer Jordan Hare. Supporting cast members include former Miss World Australia Erin Holland, J.R. Reyne (Neighbours), Libby Asciak (Here Come The Habibs), Johnny Boxer (Fat Pizza vs Housos), Terry Serio (Janet King), Jeremy Ambrum (Cleverman, Mabo) and Amanda Muggleton (City Homicide, Prisoner). Seven’s Director of Network Production, Brad Lyons, said: “Seven is the home of Australian drama and we’re immensely proud to be bringing another great Australian story to the screen. Jessica Mauboy is an amazing talent and this is a terrific yarn full of warmth, humour and music and we can’t wait to share it with everyone.” Screentime CEO Rory Callaghan, added: "We are delighted that this heart-warming production has attracted a cast of such depth and calibre.” THE SECRET DAUGHTER is a Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production for Channel Seven produced with the financial assistance of Screen Australia and Screen NSW.