Effects of Earthflows on Stream Channel and Valley Floor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Landslides.Indd

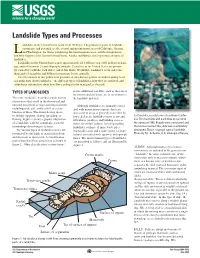

Landslide Types and Processes andslides in the United States occur in all 50 States. The primary regions of landslide occurrence and potential are the coastal and mountainous areas of California, Oregon, Land Washington, the States comprising the intermountain west, and the mountainous and hilly regions of the Eastern United States. Alaska and Hawaii also experience all types of landslides. Landslides in the United States cause approximately $3.5 billion (year 2001 dollars) in dam- age, and kill between 25 and 50 people annually. Casualties in the United States are primar- ily caused by rockfalls, rock slides, and debris flows. Worldwide, landslides occur and cause thousands of casualties and billions in monetary losses annually. The information in this publication provides an introductory primer on understanding basic scientific facts about landslides—the different types of landslides, how they are initiated, and some basic information about how they can begin to be managed as a hazard. TYPES OF LANDSLIDES porate additional variables, such as the rate of movement and the water, air, or ice content of The term “landslide” describes a wide variety the landslide material. of processes that result in the downward and outward movement of slope-forming materials Although landslides are primarily associ- including rock, soil, artificial fill, or a com- ated with mountainous regions, they can bination of these. The materials may move also occur in areas of generally low relief. In by falling, toppling, sliding, spreading, or low-relief areas, landslides occur as cut-and- La Conchita, coastal area of southern Califor- flowing. Figure 1 shows a graphic illustration fill failures (roadway and building excava- nia. -

South Fork Coquille Watershed Analysis

DOCUMENT A 13.66/2: COQUILLE fiVE, LOWER S.F. 17 10 03 00* I C 66x 1 COQUILLE RIVER, UPPER S.F 17 1:-03 01* ' United States Q, '0) Departimnt of Agriculture THIS PUBLICATION Forest Serilce CMN FE CHECKED OUT Pacific Northwest Region 1995 JA* fSouth Fork Coquille Wate1hed Analysis Iteration 1.0 Powers Ranger Distric, Slsklyou National Forest September 1995 SOUTHERN OREGON UNWVERSiTY LIBRARY ASHLAND, OREGON 97520 United Stat. Depaenent of Agnculure Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region 1995 SOUTH FORK COQUILLE WATERSHED ANALYSIS ITERATION 1.0 I have read this analysis and it meets the Standards and Guidelines for watershed analysis required by an amendment to the Forest Plan (Record of Decision dated April 1994). Any additional evidence needed to make a decision will be gathered site-specifically as part of a NEPA document or as an update to this document. SIGNED CoQ 4 DATE q 1T2 letE District Ranger Powers Ranger District Siskiyou National Forest South Fork Coquille Watershed Analysis - September 1995 Developed by Interdisciplinary Team Members: Steve Harbert Team leader Betsy Howell Wildlife Biologist Dave Shea Botantist, Wildlife Biologist Ruth Sisko Forester Cindy Ricks Geologist Chris Parks Hydrologist Max Yager Fish Biologist Kathy Helm Writer-Editor (March-April 1995), BLM Tina Harbert Writer-Editor (May-July 1995), Powers R.D. Joe Hallett Cultural Resource Key Support: Joel King Forest Planner, Siskiyou National Forest Sue Olson Acting District Ranger, Powers R.D. (Jan-May 1995) Carl Linderman District Ranger, Powers R.D. Marshall Foster GIS, Powers R.D. Jodi Shorb Computer Assistant Linda Spencer Computer Support For Further Information, contact: Powers Ranger District Powers, OR 97466 (503) 439-3011 The policy of the United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, religion, sex, or disability, familial status, or political affiliation. -

Engineering Geologic Assessment of the Slope Movements And

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 13, 1113–1126, 2013 Natural Hazards Natural Hazards www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/13/1113/2013/ doi:10.5194/nhess-13-1113-2013 and Earth System and Earth System © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Engineering geologic assessment of the slope movements and Discussions Open Access Open Access liquefaction failures of the 23 October 2011 Van earthquakeAtmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement M = ( w 7.2) Techniques Techniques A. Karakas¸, O.¨ Coruk, and B. Dogan˘ Discussions Open Access Open Access Kocaeli University, Engineering Faculty, Department of Geological Engineering, Izmit,˙ Kocaeli, Turkey Biogeosciences Correspondence to: A. Karakas¸([email protected]) Biogeosciences Discussions Received: 30 October 2012 – Published in Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: – Revised: 29 January 2013 – Accepted: 18 April 2013 – Published: 26 April 2013 Open Access Open Access Climate Climate Abstract. On 23 October 2011, a M = 7.2 earthquake oc- 1 Introduction w of the Past of the Past curred in the Van Province in eastern Turkey, killing 604 peo- Discussions ple. The earthquake was triggered by a thrust fault due to a Earthquakes are natural events that have different effects on compression stress in the region, and caused extensive dam- the earth. Some effects severely affect humans, man-made Open Access Open Access age over a large area. Many structures in the earthquake re- structures, and nature. -

Mass Movements General Anatomy

CE/SC 10110-20110: Planet Earth Mass Movements Earth Portrait of a Planet Fifth Edition Chapter 16 Mass movement (or mass wasting) is the downslope motion of rock, regolith (soil, sediment, and debris), snow, and ice. General Anatomy Discrete slump blocks Head scarp Bulging toe Road for scale Disaster in the Andes: Yungay, Peru, 1970 Fractures rock, loosens soil particles. Seismic energy overstresses the system. Yungay, Peru, in the Santa River Valley beneath the heavily glaciated Nevado Huascarán (21,860 feet). May, 1970, earthquake occurred offshore ~100 km away - triggered many small rock falls. An 800-meter-wide block of ice was dislodged and avalanched downhill, scooping out small lakes and breaking off large masses of rock debris. Disaster in the Andes: Yungay, Peru, 1970 More than 50 million cubic meters of muddy debris traveled 3.7 km (12,000 feet) vertically and 14.5 km (9 miles) horizontally in less than 4 minutes! Main mass of material traveled down a steep valley, blocking the Santa River and burying ~18,000 people in Ranrachirca. A small part shot up the valley wall, was momentarily airborne before burying the village of Yungay. Estimated death toll = 17,000. Disaster in the Andes: Yungay, Peru, 1970 Before After Whats Left of Yungay. Common Mass Movements Rockfalls and Slides Slow Fast Debris Flows Slumping Lahars and Mudflows Solifluction and Creep These different kinds of mass movements are arranged from slowest (left) to fastest (right). Types of Mass Movement Different types of mass movement based on 4 factors: 1) Type of material involved (rock, regolith, snow, ice); 2) Velocity of the movement (slow, intermediate, fast); 3) Character of the movement (chaotic cloud, slurry, coherent mass; 4) Environment (subaerial, submarine). -

The Mink Creek Earthflow March, 1995

Forest Sciences Prince Rupert Forest Region Extension Note # 04 The Mink Creek Earthflow March, 1995 Research Issue Groups: Forest Biology Forest Growth Soils Wildlife Habitat Silviculture Timber Harvesting Ecosystem Inventory and Classification Biodiversity Figure 1. The Mink Creek earthflow retrogressed about 600 meters. Ecosystem Management Background Hydrology (sediments of glacial origin deposited We generally associate slope failures in the sea) flowed and slid rapidly Geomorphology with steep, mountainous areas. Flat into Mink Creek, near Terrace, BC. to rolling, subdued terrain is thought Spoil from the earthflow crater filled the incised channel of Mink Creek, Extension of as having a relatively low risk of landslide occurrence. This is not extending downstream approximately always the case. Sometime, between one kilometer. The debris dammed Forest Engineering mid-December, 1993 and early the creek, raised the water level by 10 January, 1994, approximately 23 meters and backed water upstream hectares of glaciomarine sediments 1200 meters. Forest Sciences, Prince Rupert Forest Region Bag 5000, Smithers, BC V0J 2N0 847-7500 (FAX 847-7217) ocean water filled the valley, creating a fjord. Glacial retreat up the Kitsumkalum-Kitimat Trough was relatively rapid, although there were several periods when the ice front was stable. During one such period, the snout of the stable, calving glacier was situated near the present location of Thornhill. Sediment- laden meltwaters poured from the ice front. Gravels and sands were deposited near the snout of the glacier forming a large sandur, or outwash plain (Terrace Airport). Smaller clay and silt particles remained suspended in the sea much longer and were deposited further from the ice front, forming silty-clay deposits such as those found at Mink Creek. -

North and South Forks Little Butte Creek Key Watershed Water Quality

Water Quality Restoration Plan Southern Oregon Coastal Basin North and South Forks Little Butte Creek Key Watershed Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Medford District Ashland Resource Area Butte Falls Resource Area Lakeview District Klamath Falls Resource Area May 2006 North and South Forks Little Butte Creek Key Watershed at a Glance Hydrologic Unit Code Number (Little 1710030708 Butte Creek) WQRP Area/Ownership Total: 125,778 acres BLM: 26,959 acres (21%) U. S. Forest Service: 59,875 acres (48%) Bureau of Reclamation: 5 acres (<.01%) Private: 38,939 acres (31%) 303(d) Stream Miles Assessed Total: 65.4 miles BLM Ownership: 15.7 miles 303(d) Listed Parameters Temperature, Sedimentation, E. Coli, pH Key Resources and Uses Salmonids, domestic, aesthetic Known Human Activities Agriculture, forestry, roads, recreation, rural residential development Natural Factors Geology: volcanic Soils: various series and complexes Statement of Purpose This water quality restoration plan is prepared to meet the requirements of Section 303(d) of the 1972 Federal Clean Water Act. Table of Contents Page Element 1 Condition Assessment and Problem Description 1 A. Introduction 1 B. Watershed Characterization 4 C.Temperature 16 D. Sedimentation 23 E.E.Coli 31 F.pH 34 Element 2 Goals and Objectives 36 Element 3 Proposed Management Measures 39 Element 4 Time Line for Implementation 40 Element 5 Responsible Parties 41 Element 6 Reasonable Assurance of Implementation 41 Element 7 Monitoring and Evaluation 42 Element 8 Public Involvement 44 Element 9 Costs and Funding 44 Element 10 Citation to Legal Authorities 45 References 46 List of Preparers 48 List of Tables Page 1. -

Sediment Yield, Spatial Characteristics, and the Long-Term

Sediment yield, spatial characteristics, and the long-term evolution of active earthfl ows determined from airborne LiDAR and historical aerial photographs, Eel River, California Benjamin H. Mackey†, and Joshua J. Roering Department of Geological Sciences, 1272 University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403, USA ABSTRACT period, equating to a regional yield of 1100 by sliding along transient shear surfaces with t km–2 yr–1 (~0.45 mm/yr) if distributed across a degree of internal deformation or fl ow. They In mountainous landscapes with weak, the study area. As such, a small fraction of span a range of landslide failure styles and have fi ne-grained rocks, earthfl ows can dominate the landscape can account for half of the re- been variably described as landslide complexes erosion and landscape evolution by supply- gional denudation rate estimated from sus- (Iverson, 1986a), landslides (Schulz et al., ing sediment to channels and controlling pended sediment records (2200 t km–2 yr–1 or 2009b), earth slides (Cruden and Varnes, 1996), hillslope morphology. To estimate the con- ~0.9 mm/yr). We propose a conceptual model and mudslides (Chandler and Brunsden, 1995; tribution of earthfl ows to regional sediment for long-term earthfl ow evolution wherein Glastonbury and Fell, 2008). Hereafter, we budgets and identify patterns of landslide ac- earthfl ows experience intermittent activity use the term earthfl ow as advocated by Hungr tivity, earthfl ow movement needs to be quan- and long periods of dormancy when limited et al. (2001) to describe large, slow-moving tifi ed over signifi cant spatial and temporal by the availability of readily mobilized sedi- landslides with macroscale, fl ow-like morphol- scales. -

Landslide Types and Processes

Chapter Three Landslide Types and Processes David J. Varnes3 It is the purpose of this chapter to re- geology, and hence lie outside the prov- view the whole range of earth move- ince of the committee. ments that may properly be regarded as landslides and to classify these move- Types of Landslides ments according to factors that have some bearing on prevention or control. CLASSIFICATION As defined for use in this volume the term "landslide" denotes downward and Many classifications have already been outward movement of slope-forming ma- proposed for earth movements, based terials composed of natural rock, soils, variously on the kind of . material, type artificial fills, -or combinations of these of movement, causes, and many other materials. The moving mass may pro- factors. There are, in. fact, so many such ceed by any one of three principal types schemes embedded with varying degrees of movement: falling, sliding, or flowing, of firmness in geological and engineering or by their combinations. Parts of a literature that the committee has ap- landslide may move upward while other proached the question of a "new" classi- parts move downward. The lower limit fication with considerable misgivings. As of the rate of movement of landslide ma- Terzaghi has stated (1950, p. 88), "A terial is restricted in this book by the phenomenon involving such a multitude economic aspect to that actual or po- of combinations between materials and tential rate of movement which provokes disturbing agents opens unlimited vistas correction or maintenance. Normal sur- for the classification enthusiast. The re- ficial creep is excluded. -

Mass Wasting

Frank Press, Raymond Siever, John Grotzinger, and Thomas H. Jordan Mass Wasting Understanding Earth Process by which Fourth Edition material moves downslope under Chapter 12: Mass the force of gravity Wasting Copyright © 2004 by W. H. Freeman & Company 1 2 Factors Influencing Mass Movement Mass Movement is Classified on the Basis of: • Nature of slope materials • Nature of material • Steepness of slope • Velocity of movement • Water content • Nature of movement • Slope stability 3 4 Mass Movement Depends on Water Content 5 6 Water Content Lose of Steep slopes vegetations and in damp sand root systems maintained by increases moisture susceptibility of between soils to erosion grains and mass movement 7 8 Types of Rock Mass Movement • Rock fall • Rock slide • Rock avalanche 9 10 Rock Fall Rockfall in Zion National Park 11 12 Rockslide Rockslide The rapid movement of large blocks of detached bedrock sliding more or less as a unit 13 14 Rockslide Rock Avalanche The rapid* mass movement of broken rock material, often riding on a cushion of trapped air. Usually triggered b y an earthquake. *10’s to 100’s of km/hr 15 16 Rock Avalanches Triggered by an Rock Avalanche Earthquake (Nov. 3, 2002) in Alaska 17 18 Types of Unconsolidated Mass Creep Movement Unconsolidated Flows The downhill movement of soil and other debris, typically at rates of Creep about 1 to 10 mm/year Earth Flow Increased velocity Debris Flow Earth Flow 19 20 Evidence of Creep 21 22 Earthflow Earthflow A fluid movement of relatively fine‐ grained material, e.g. soil, weathered shale, and clay. -

Landslide Types and Processes

Landslide Types and Processes andslides in the United States occur in all 50 States. The primary regions of landslide occurrence and potential are the coastal and mountainous areas of California, Oregon, Land Washington, the States comprising the intermountain west, and the mountainous and hilly regions of the Eastern United States. Alaska and Hawaii also experience all types of landslides. Landslides in the United States cause approximately $3.5 billion (year 2001 dollars) in dam- age, and kill between 25 and 50 people annually. Casualties in the United States are primar- ily caused by rockfalls, rock slides, and debris flows. Worldwide, landslides occur and cause thousands of casualties and billions in monetary losses annually. The information in this publication provides an introductory primer on understanding basic scientific facts about landslides—the different types of landslides, how they are initiated, and some basic information about how they can begin to be managed as a hazard. TYPES OF LANDSLIDES porate additional variables, such as the rate of movement and the water, air, or ice content of The term “landslide” describes a wide variety the landslide material. of processes that result in the downward and outward movement of slope-forming materials Although landslides are primarily associ- including rock, soil, artificial fill, or a com- ated with mountainous regions, they can bination of these. The materials may move also occur in areas of generally low relief. In by falling, toppling, sliding, spreading, or low-relief areas, landslides occur as cut-and- La Conchita, coastal area of southern Califor- flowing. Figure 1 shows a graphic illustration fill failures (roadway and building excava- nia. -

Comparison of Two Landslides and Related Outburst

COMPARISON OF LANDSLIDES AND THEIR RELATED OUTBURST FLOOD DEPOSITS, OWYHEE RIVER, SOUTHEASTERN OREGON _________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Geology _________________________________________________ by Shannon Marian Othus May 2008 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Shannon Marian Othus Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY _________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Lisa L. Ely, Committee Chair _________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Beth Pratt-Sitaula _________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Karl Lillquist _________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Wendy Bohrson, Geology Department Chair _________________ ________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT COMPARISON OF LANDSLIDES AND THEIR RELATED OUTBURST FLOOD DEPOSITS, OWYHEE RIVER, SOUTHEASTERN OREGON by Shannon Marian Othus May 2008 Numerous landslides have entered the Owyhee River canyon north of Rome, Oregon. As the river flows through different lithologic units, the style of mass wasting changes from large slump events and small rock falls to large earthflows. The change in mechanism of mass wasting from upstream to downstream seems to depend on several factors: (1) the ratio of the -

Earth Flows: Rc Ij&O

BU~': ·· ' ~.X-t~ .:1 kt..-. .--~~ Earth Flows: rc iJ&O. "' ~,. Morphology, Mobilization, and Movement G E 0 L 0 G I C A L S U R V E Y P R 0 F E S S I 0 N A L P A P E R 1 2 6 4 ~~ .BURtAU OF MIN.fiS LIBRARY; SPOKANE. WASH. MAR 151984 PltA!)f '<ETURN lO LIBRARY Earth Flows: Morphology, Mobilization, and Movement By DAVID K. KEEFER and ARVID M. JOHNSON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1264 A study of the factors controlling earth-flow occurrence and the velocity of an active earth flow UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1983 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Keefer, David Knight Earth flows: Morphology, mobilization, and movement. (Geological Survey professional paper 1264) Bibliography: p. 53-56 Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16:1264 1. Earthflows. 2. Earthflows-California. I. Johnson, Arvid M. II. Title. III. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Pro fessional Paper 1264. QE599.A2K43 1983 551.3 83--600499 For ~ale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 The Davilla Hill earth-flow complex-Continued I ntrod ucti on --------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Studies of active earth flows and ground-water conditions, Previous studies -------------------------------------------------------- 2 1974-78--Continued Classification