Najm Hosain Syed: a Literary Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

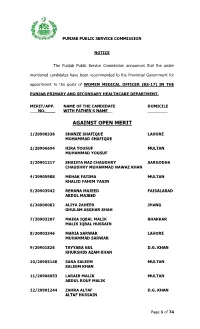

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB PRIMARY AND SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/20900338 SHANZE SHAFIQUE LAHORE MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUE 2/20906694 HIRA YOUSUF MULTAN MUHAMMAD YOUSUF 3/20901217 SHAISTA NAZ CHAUDHRY SARGODHA CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD NAWAZ KHAN 4/20905988 MEHAK FATIMA MULTAN KHALID FAHIM YASIN 5/20903942 REHANA MAJEED FAISALABAD ABDUL MAJEED 6/20900082 ALIYA ZAHEER JHANG GHULAM ASGHAR SHAH 7/20903207 MAIRA IQBAL MALIK BHAKKAR MALIK IQBAL HUSSAIN 8/20903346 MARIA SARWAR LAHORE MUHAMMAD SARWAR 9/20901826 TAYYABA GUL D.G. KHAN KHURSHID AZAM KHAN 10/20905148 SARA SALEEM MULTAN SALEEM KHAN 11/20906053 LARAIB MALIK MULTAN ABDUL ROUF MALIK 12/20901244 ZAHRA ALTAF D.G. KHAN ALTAF HUSSAIN Page 1 of 74 From Pre-page 1315 posts of Women Medical Officer (BS-17) in the Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.__ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 13/20903132 ZAHRA MUSHTAQ RAWALPINDI MUHAMMAD MUSHTAQ AHMAD 14/20901604 MARIA FATIMA OKARA QURBAN ALI 15/20901854 HAFIZA AMMARA SIDDIQI FAISALABAD MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE 16/20904115 QURAT-UL-AIN SARWAR LAHORE MANZOOR SARWAR CHAUDHARY 17/20901733 AALIA BASHIR D.G. KHAN SHEIKH DAUD ALI 18/20905234 FARVA KOMAL M. GARH GHULAM HAIDER KHAN 19/20901333 SADIA MALIK SARGODHA GHULAM MUHAMMAD 20/20904405 ZARA MAHMOOD RAWALPINDI MAHMOOD AKHTER 21/20900565 MARIA IRSHAD HAFIZABAD IRSHAD ULLAH 22/20902101 FARYAL ASIF SARGODHA ASIF ILYAS 23/20901525 MAHAM FATIMA M. -

Cultural Festivals: an Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: a Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 03, Issue No. 2, July - December 2017 Syed Ali Raza* Cultural Festivals: An Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: A Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City Abstract The Sufism has unique methodology of the purification of consciousness which keeps the soul alive. The natural corollary of its origin and development brought about religo-cultural changes in Islam which might be different from the other part of Muslim world. Sufism has been explained by many people in different ways and infect is the purification of the heart and soul as prescribed in the holy Quran by God. They preach that we should burn our hearts in the memory of God. Our existence is from God which can only be comprehended with the help of blessing of a spiritual guide in the popular sense of the world. Sufism is the way which teaches us to think of God so much that we should forget our self. Sufism is the made of religious life in Islam in which the emphasis is placed, not on the performance of external ritual but on the activities of the inner-self’ in other words it signifies Islamic mysticism. Beside spirituality, the Sufi’s contributed in the promotion of performing art, particularly the music. Pakistan has been the center of attraction for the Sufi Saints who came from far-off areas like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Arabia. The people warmly welcomes them, followed their traditions and preaching’s and even now they celebrates their anniversaries in the form of Urs. -

United Punjab: Exploring Composite Culture in a New Zealand Punjabi Film Documentary

sites: new series · vol 16 no 2 · 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11157/sites-id445 – article – SANJHA PUNJAB – UNITED PUNJAB: EXPLORING COMPOSITE CULTURE IN A NEW ZEALAND PUNJABI FILM DOCUMENTARY Teena J. Brown Pulu,1 Asim Mukhtar2 & Harminder Singh3 ABSTRACT This paper examines the second author’s positionality as the researcher and sto- ryteller of a PhD documentary film that will be shot in New Zealand, Pakistan, and North India. Adapting insights from writings on Punjab’s composite culture, the film will begin by framing the Christchurch massacre at two mosques on 15 March 2019 as an emotional trigger for bridging Punjabi migrant communi- ties in South Auckland, prompting them to reimagine a pre-partition setting of ‘Sanjha Punjab’ (United Punjab). Asim Mukhtar’s identity as a Punjabi Muslim from Pakistan connects him to the Punjabi Sikhs of North India. We use Asim’s words, experiences, and diary to explore how his insider role as a member of these communities positions him as the subject of his research. His subjectivity and identity then become sense-making tools for validating Sanjha Punjab as an enduring storyboard of Punjabi social memory and history that can be recorded in this documentary film. Keywords: united Punjab; composite culture; migrants; Punjabis; Pakistani; Muslims; Sikhs; South Auckland. INTRODUCTION The concept ‘Sanjha Punjab – United Punjab’ cuts across time, international and religious boundaries. On March 15, 2019, this image of a united Punjab inspired Pakistani Muslim Punjabis and Indian Sikh Punjabis to cooperate in support of Pakistani families caught in the terrorist attacks at Al Noor Masjid and Linwood Majid in Christchurch. -

Shah Hussain - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Shah Hussain - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Shah Hussain(1538–1599) Shah Hussain was a Punjabi Sufi poet who is regarded as a Sufi saint. He was the son of Sheikh Usman, a weaver, and belonged to the Dhudha clan of Rajputs. He was born in Lahore (present-day Pakistan). He is considered a pioneer of the Kafi form of Punjabi poetry. Shah Hussain's love for a Brahmin boy called "Madho" or "Madho Lal" is famous, and they are often referred to as a single person with the composite name of "Madho Lal Hussain". Madho's tomb lies next to Hussain's in the shrine. His tomb and shrine lies in Baghbanpura, adjacent to the Shalimar Gardens. His Urs (annual death anniversary) is celebrated at his shrine every year during the "Mela Chiraghan" ("Festival of Lights"). <b>Kafis of Shah Hussain</b> Hussain's poetry consists entirely of short poems known as Kafis. A typical Hussain Kafi contains a refrain and some rhymed lines. The number of rhymed lines is usually between four and ten. Only occasionally is a longer form adopted. Hussain's Kafis are also composed for, and have been set to, music deriving from Punjabi folk music. Many of his Kafis are part of the traditional Qawwali repertoire. His poems have been performed as songs by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Parveen and Noor Jehan, among others. Here are three examples, which draw on the love story of Heer Ranjha: "Ni Mai menoon Khedeyan di gal naa aakh Ranjhan mera, main Ranjhan di, Khedeyan noon koodi jhak Lok janey Heer kamli hoi, Heeray da var chak" "Do not talk of the Khedas to me, mother. -

Newsletter 3

MI French Interdisciplinary Mission in Sindh FS Edito The first half of the year 2009 was very busy for several reasons. The study group “History and Sufism in the Valley of the Indus” organized a one-day conference in January on Plurality of sources and interdisciplinary approach: a case study of Sehwan Sharif in Sindh. It was attended by senior scholars such as 9 Claude Markovits (CNRS-CEIAS) or Monique Kervran (CNRS), as well as doctoral students such as Annabelle Collinet and Johanna Blayac, and also 0 “post-docs” such as Frédérique Pagani (p. 4-5). The conference was also attended by Sindhis from the very small community settled in Paris. 0 In the same period, two professors working on Sufism in Pakistan were invited by the EHESS. Pnina Werbner, professor of Anthropology at Keele University, was 2 invited by IISMM, an institute centred on the Muslim world and affiliated to r EHESS. Professor Werbner delivered conferences on topics related to Sufism, e and she also headed a workshop for Ph.D. students. She wrote a seminal paper on Transnationalism and Regional Cults: The Dialectics of Sufism in the b Plurivocal Muslim World (p. 6-7) which will be put online on the forthcoming MIFS website. Professor Richard K. Wolf, professor of Ethnomusicology at Harvard University, was invited in May by the EHESS, by Marie-Claude Mahias (CNRS-CEIAS). He tem delivered four lectures, the first one devoted to Nizami Sufism in Karachi and Delhi. Professor Wolf gave a talk at the study group “History and Sufism in the p Valley of the Indus” on “Music in Shrine Sufism of Pakistan” (CEIAS, 28 May 2009). -

1. Introduction “Bhand-Marasi”

1. INTRODUCTION “BHAND-MARASI” A Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre Bhand-Marasi is a Folk-Form of Punjabi theatre. My project is based on Punjabi folk-forms. I am unable to work on all the existing folk-forms of Punjab because of limited budget & time span. By taking in concern the current situation of the Punjabi folk theatre, I together with my whole group, strongly feel that we should put some effort in preventing this particular folk-form from being extinct. Bhand-Marasi had been one of the chief folk-form of celebration in Punjabi culture. Nowadays, people don’t have much time to plan longer celebrations at homes since the concept of marriage palaces & banquet halls has arrived & is in vogue these days to celebrate any occasion in the family. Earlier, these Bhand-Marasis used to reach people’s home after they would get the wind of any auspicious tiding & perform in their courtyard; singing holy song, dancing, mimic, becoming characters of the host family & making or enacting funny stories about these family members & to wind up they would pray for the family’s well-being. But in the present era, their job of entertaining the people has been seized by the local orchestra people. Thus, the successors of these Bhand- Marasis are forced to look for other jobs for their living. 2. OBJECTIVE At present, we feel the need of “Data- Creation” of this Folk Theatre-Form of Punjab. Three regions of Punjab Majha, Malwa & Doaba differ in dialect, accent & in the folk-culture as well & this leads to the visible difference in the folk-forms of these regions. -

A Study of Educational Opportunity for Punjabi Youth. Final Report. INSTITUTION South Asian American Education Association, Stockton, CA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 236 276 UD 023 154 AUTHOR Gibson, Margaret A. TITLE Home-School-Community Linkages: A Study of Educational Opportunity for Punjabi Youth. Final Report. INSTITUTION South Asian American Education Association, Stockton, CA. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 83 GRANT NIE-G-80-0123 NOTE 270p.; Funding was provided by the Home, Community, and Work Program. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; *Cultural Influences; Educational Opportunities; *Family School Relationship; High Schools; *Immigrants; *Indians; Minority Groups; *Parent Attitudes; Religious Cultural Groups; School Community Relationship; Student Behavior; *Success IDENTIFIERS California; *Sikhs ABSTRACT This report presents findings from ethnographic research that focused on factors which promote and impede educational opportunity for Punjabi Sikh immigrants in "Valleyside," an agricultural town in California. The report is divided into two parts. Part one considers the setting and the sociocultural context for schooling ia "Valleyside." Drawing from interviews with Punjabi and non-immigrant residents, parents' views of life in America, job opportunities, family structure, social relations, and child rearing are described. Background on Punjabis in India is provided.Their reasons for immigrating to the United States, their theory of success, and their life strategies are explored. In addition, social relations between'Punjabis and members of the mainstream majority are discussed. This section closes with a comparative analysis of child rearing, emphasizing those patterns most directly related to school performance at the secondary level. The second half of the report focuses on schooling itself by examining social, structural, and cultural factors which influence educational opportunity, home-school relations, and school response patterns. -

Tona , the Folk Healing Practices in Rural Punjab

TONA, THE FOLK HEALING PRACTICES IN RURAL PUNJAB, PAKISTAN AZHER HAMEED QAMAR PhD student Norwegian Centre for Child Research (NOSEB) Norwegian University of Science and Technology Pavilion C, Dragvoll, Loholt allé 87, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Consulting religion and magic for healing is an important aspect of healing belief practices. Magical thinking provides space for culturally cognitive patterns to inte- grate belief practices. Tona, a layman’s approach to healing that describes magico- religious (fusion of magic and religion) and secular magic practices in rural Pun- jab, Pakistan, is an example of magico-religious and secular magical practice. The purpose of this study is to analyse tona as it is practiced to cure childhood diseases (sokra and sharwa) in Muslim Punjab, Pakistan. This is an ethnographic study I con- ducted using participant observation and unstructured interviews as the primary research methods. The study produced an in-depth analysis of tona as a healing belief practice in the light of Frazer’s principles of magical thinking and sympa- thetic magic. The study provides a deeper understanding of the magical thinking in magico-religious healing belief practices. KEYWORDS: childcare beliefs • folk remedies • religion • magic • magico-reli- gious healing • magical thinking INTRODUCTION Healthcare beliefs as an elementary component of the basic human instinct of survival exist in all cultures. Consulting religion and magic to control and manipulate nature and contact divine power is an important aspect of healing belief practices. These belief practices are religious, non-religious or may present a fused picture of religious/non- religious beliefs. -

Historical Constructions of Ethnicity: Research on Punjabi Immigrants in California

Historical Constructions of Ethnicity: Research on Punjabi Immigrants in California KAREN LEONARD IMMIGRANTS FROM the Punjab province of India came to California at the turn of the twentieth century and settled in the state's major agricultural valleys. About five hundred of these men married Mexican and Mexican-American women, creating a Punjabi Mexican second generation which thought of itself as "Hindu" (the name given to immi grants from India in earlier decades). This biethnic community poses interesting questions about the construction and transformation of ethnic identity, and the interpretations of outsiders contrast with those of the pioneers and their descendants. These interpretations direct attention to the historical contingency of ethnic identity and to the many voices which participate in its definition. Punjabi Immigrants and the Punjabi-Mexican Families The community of immigrants from South Asia has changed dramati cally over time. Table 1 shows the small numbers of Asian Indians and their concentration in rural California in the first half of the twentieth century. While the figures do not indicate place of origin in South Asia, the overwhelming majority of the pre-1946 immigrants were men from the Punjab in northwestern India.1 This table also shows the effect of later changes in citizenship and immigration laws: a large increase in numbers, diffusion throughout the United States, and a shift to urban centers. In 1946, the Luce-Celler Bill made Asian Indians eligible for citizenship, and the oldtimers were allowed to sponsor a small number of new immigrants (the 1924 National Origins Act, applicable once Indians could become citizens, established an annual quota of 100 for India). -

E:\2019\Other Books\Final\Darshan S. Tatla\New Articles\Final Articles.Xps

EXPLORING ISSUES AND PROJECTS FOR COOPERATION BETWEEN EAST AND WEST PUNJAB WORLD PUNJABI CENTRE Monographs and Occasional Papers Series The World Punjabi Centre was established at Punjabi University, Patiala in 2004 at the initiative of two Chief Ministers of Punjabs of India and Pakistan. The main objective of this Centre is to bring together Punjabis across the globe on various common platforms, and promote cooperation across the Wagah border separating the two Punjabs of India and Pakistan. It was expected to have frequent exchange of scholarly meetings where common issues of Punjabi language, culture and trade could be worked out. This Monograph and Occasional Papers Series aims to highlight some of the issues which are either being explored at the Centre or to indicate their importance in promoting an appreciation and understanding of various concerns of Punjabis across the globe. It is hoped other scholars will contribute to this series from their respective different fields. Monographs 1. Exploring Possibilities of Cooperation among Punjabis in the Global Context – (Proceedings of the Conference held in 2006), Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 63pp. 2. Bhagat Singh and his Legend, (Papers Presented at the Conference in 2007) Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 280pp. Occasional Papers Series 1. Exploring Issues and Projects For Cooperation between East and West Punjab, Balkar Singh & Darshan S. Tatla, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. 1, 2019 2. Sikh Diaspora Archives: An Outline of the Project, Darshan S. Tatla & Balkar Singh, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. -

In the Name of Allah, Themostbeneficent

* n Z IN THE NAME OFALLAH, THE MOSTBENEFICENT, THE MOSTMERCIFUL IMPACTS OF ENGLISH CRITICISM ON PUNJABI CRITICISM 1947-2005 (An analytical and critical study) (Session 2003-2004) (Thesis Ph.D Punjabi) BB k$ SUBMITTED BY NAHEED QADIR Lecturer, Govt. Islamia College for women, Faisalabad SUPERVISOR Dr. NAHEED ZAMAN KHAN Associate Prof. Department of Punjabi, PUNJABI DEPARTMENT PUNJAB UNIVERSITY ORIENTAL COLLEGE LAHORE 2010 IMPACTS OF ENGLISH CRITICISM ON PUNJABI CRITICISM 1947-2005 (An analytical and critical study) (Session 2003-2004) (Thesis Ph.D Punjabi) aa Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirement of degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Punjabi, from Punjabi Department, in the University of the Punjab, for the year 2003 - 2004 SUBMITTED BY NAHEED QADIR Lecturer, Govt. Islamia College for women, Faisalabad SUPERVISOR Dr. NAHEED ZAMAN KHAN Associate Prof. Department of Punjabi. PUNJABI DEPARTMENT PUNJAB UNIVERSITY, ORIENTAL COLLEGE LAHORE 2010 Permission has been granted by the University of the Punjab, reference No. I/735-ACAD, Dated. 15.02.2010 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is a result of my individual research andIhave not submitted this thesis concurrently to any other University for any degree whatsoever.I NAHEED QADIR TOMYPARENTS WHO TAUGHTME TO CAREANDREASON AND TO TAYYABA FATIMA WHO PUTITALL TOGETHER AND MORE Contents Title Page No. Preface i-iv Chapter 1 Literary criticism: an over view 1. Introduction 1 2. Criticism and literature 4 3. Critical theory 7 4. types of literary criticism 9 o Legislative criticism o Judicial criticism o Theoretical criticism o Evaluative criticism o Historical criticism o Biographical criticism o Comparative criticism o Descriptive criticism o Impressionistic criticism o Textual criticism o Psychological criticism o Sociological and Marxist Criticism o Archetypal criticism 5. -

Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth

Winner List Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth Multan Division NIC ApplicantName GuardianName Address WinOrder Distt. Khanewal Jahanian (Bolan) Key Used: aghakhurm 3610102439763 ABDUL HAFEEZ M. HANIF 105/10R JAHANIAN DIST. 1 3610102595791 LIAQAT HUSSAIN ABDUL HAMEED THATA SADIQABAD, TEH JAHANIA, 2 DISTT. KHANWALA 3610102707797 GHAZANFAR HASSAN MOHAMMAD SHAKAR H NO. 225, BLOCK NO. 5, JAHANIAN 3 DISTT. KHANEWAL. 3610180513779 WASEEM ALI M. SARWAR CHAK NO. 121/10-R TEH. JAHANIA 4 DISTT. KHANEWAL 3520227188361 MOHAMMAD JAVED MOHAMMAD SHAFI FLAT NO 752C BLOCK Q MODEL TOWN 5 LAHORE 3610141795247 Muhammad Shahid Shahzada Zahid Raza Rahim Shah Road H/NO.164/A Jinnah 6 Abdil Jahanian D 3610132117859 MUHAMMAD DILSHAD ALI JAMSHAD ALI CHAK NO. 135/10R, TEHSEEL 7 JAHANIAN DISTT. KHANEWAL 3610102391383 TAHIR ABBAS AZIZ AHMED CHAK KHRIA POST 99-10R RAHEEM 8 SHAH 3610180588801 SOHAIL IJAZ IAJZ AHMED CHAK NO 116/10-R NEW TEH 9 JAHANIAN KHANEWAL 3610112010659 MOHAMMAD RIAZ FALIK SHER CHAK NO 157/10-R P/O JUNGLE 10 MARYALA JHASIL JAHANIA 3610166557189 MUHAMMAD THIR MUHAMMAD SLEEM CAHK NO 135/10R 11 3610171420543 TOQEER HUSSAIN SAEED SAEED AKHTAR CHAK NO. 132/10R, P.O. THATHA 12 SADIQ ABAD TEH JHANI 3610102461071 MUHAMMAD NASRULLAH KHUSHI MUHAMMAD BLOCK # 4 JAHANIAN KWL 13 3610181422213 HAFIZ ASIF JAVED ABDUL GHAFAR CHAK NO. 107/10-R TEH. JAHANIAN 14 DISTT. KHANEWAL 3610115748627 MUHAMMAD ASIF MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO 114-10R JAHIANIAN DIST 15 KHANEWAL 3610154828857 ASIF BASHIR BASHIR AHMAD MAMTAZ LAKR MANDI TEH. JAHANIAN DISTT. 16 KHANEWAL 3610102391373 MUHAMMAD SARWAR MUHAMMAD NAZIR AHMED OPP BHATTI SERVICE STATION SIAL 17 TOWN JHN TEH JHN D 3610102750511 ASIF ISMAIL LIAQAT ALI CH.