Social Welfare Functions of the Shrine of Bari Imam How the Shrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

The Ultimate Dimension of Life’ During His(RA) Lifetime

ABOUT THE BOOK This book unveils the glory and marvellous reality of a spiritual and ascetic personality who followed a rare Sufi Order called ‘Malamatia’ (The Carrier of Blame). Being his(RA) chosen Waris and an ardent follower, the learned and blessed author of the book has narrated the sacred life style and concern of this exalted Sufi in such a profound style that a reader gets immersed in the mystic realities of spiritual life. This book reflects the true essence of the message of Islam and underscores the need for imbibing within us, a humane attitude of peace, amity, humility, compassion, characterized by selfless THE ULTIMATE and passionate love for the suffering humanity; disregarding all prejudices DIMENSION OF LIFE and bias relating to caste, creed, An English translation of the book ‘Qurb-e-Haq’ written on the colour, nationality or religion. Surely, ascetic life and spiritual contemplations of Hazrat Makhdoom the readers would get enlightened on Syed Safdar Ali Bukhari (RA), popularly known as Qalandar the purpose of creation of the Pak Baba Bukhari Kakian Wali Sarkar. His(RA) most devout mankind by The God Almighty, and follower Mr Syed Shakir Uzair who was fondly called by which had been the point of focus and Qalandar Pak(RA) as ‘Syed Baba’ has authored the book. He has been an all-time enthusiast and zealous adorer of Qalandar objective of the Holy Prophet Pak(RA), as well as an accomplished and acclaimed senior Muhammad PBUH. It touches the Producer & Director of PTV. In his illustrious career spanning most pertinent subject in the current over four decades, he produced and directed many famous PTV times marred by hatred, greed, lust, Plays, Drama Serials and Programs including the breathtaking despondency, affliction, destruction, and amazing program ‘Al-Rehman’ and the magnificient ‘Qaseeda Burda Sharif’. -

New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab

Asia Society and CaravanSerai Present New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab Saturday, April 28, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 2 hours with no intermission New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan Performers Arooj Afab lead vocals Bhrigu Sahni acoustic guitar Jorn Bielfeldt percussion Arif Lohar lead vocals/chimta Qamar Abbas dholak Waqas Ali guitar Allah Ditta alghoza Shehzad Azim Ul Hassan dhol Shahid Kamal keyboard Nadeem Ul Hassan percussion/vocals Fozia vocals AROOJ AFTAB Arooj Aftab is a rising Pakistani-American vocalist who interprets mystcal Sufi poems and contemporizes the semi-classical musical traditions of Pakistan and India. Her music is reflective of thumri, a secular South Asian musical style colored by intricate ornamentation and romantic lyrics of love, loss, and longing. Arooj Aftab restyles the traditional music of her heritage for a sound that is minimalistic, contemplative, and delicate—a sound that she calls ―indigenous soul.‖ Accompanying her on guitar is Boston-based Bhrigu Sahni, a frequent collaborator, originally from India, and Jorn Bielfeldt on percussion. Arooj Aftab: vocals Bhrigu Sahni: guitar Jorn Bielfeldt: percussion Semi Classical Music This genre, classified in Pakistan and North India as light classical vocal music. Thumri and ghazal forms are at the core of the genre. Its primary theme is romantic — persuasive wooing, painful jealousy aroused by a philandering lover, pangs of separation, the ache of remembered pleasures, sweet anticipation of reunion, joyful union. Rooted in a sophisticated civilization that drew no line between eroticism and spirituality, this genre asserts a strong feminine identity in folk poetry laden with unabashed sensuality. -

Cultural Festivals: an Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: a Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 03, Issue No. 2, July - December 2017 Syed Ali Raza* Cultural Festivals: An Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: A Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City Abstract The Sufism has unique methodology of the purification of consciousness which keeps the soul alive. The natural corollary of its origin and development brought about religo-cultural changes in Islam which might be different from the other part of Muslim world. Sufism has been explained by many people in different ways and infect is the purification of the heart and soul as prescribed in the holy Quran by God. They preach that we should burn our hearts in the memory of God. Our existence is from God which can only be comprehended with the help of blessing of a spiritual guide in the popular sense of the world. Sufism is the way which teaches us to think of God so much that we should forget our self. Sufism is the made of religious life in Islam in which the emphasis is placed, not on the performance of external ritual but on the activities of the inner-self’ in other words it signifies Islamic mysticism. Beside spirituality, the Sufi’s contributed in the promotion of performing art, particularly the music. Pakistan has been the center of attraction for the Sufi Saints who came from far-off areas like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Arabia. The people warmly welcomes them, followed their traditions and preaching’s and even now they celebrates their anniversaries in the form of Urs. -

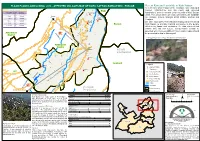

Recent Rain and Landslide in Kotli Sattian

FLASH FLOOD/LANDSLIDING 2016 - AFFECTED VILLAGES MAP OF KOTLI SATTIAN,RAWALPINDI - PUNJAB Recent Rain and Landslide in Kotli Sattian Recent rains which triggered the Landslide have damaged List of Affected Village !> houses, infrastructure and link roads and uprooted !> Bagh !> SN Villages Tehsil District !> Chhajana!> hundreds of trees in several union councils of Kotli Sattian 1 Chaniot Kotli Rawalpindi !> ! Sattian !> !> !> !> !> !> tehsil. The areas which are most affected by the landslide 2 Kamra Kotli Rawalpindi Murree !> !> Sattian !> are Chaniot, Kamra, Wahgal, Malot Sattian, Burhad and 3 Wahgal Kotli Rawalpindi _ !> Malot "' Sattian !> Sattian !> !> Chajana. 4 Malot Kotli Rawalpindi !> !> !> ! Sattian Sattian !> Wahgal ! On 26th April 2016 Prime Minister Nawaz Shareef visited !>!> 5 Burhad Kotli Rawalpindi !> ! Sattian !> !> Poonch !> !> !> Kotli Sattian to provide financial assistance to the people 6 Chhajana Kotli Rawalpindi ! !> Sattian ! affected by floods and landslides. He also directed that Kotli Chijan Road Kotli Chijan Road Patriata Road Patriata Road !> victims who did not receive compensation should be "'!> !> !> !> provided with cheques within 24 hours and a report should Á !> !> !> Abbottabad !> !> Kotli Sattain To Mureee 40 KM !> be presented to him in this regard. District !> !> !>!> ! !> To Murree To A Damaged House View in Village Malot Sattian,Tehsil Kotli Sattain Islamabad-MureeIslamabad-Muree ExpresswayExpressway !> !> !> !> !> 4ö !> !>!> Rawalpindi ! District Kotli ! "' "'Sattian "'! A Z A D "'_ A Z A D !> -

A Drama of Saintly Devotion Performing Ecstasy and Status at the Shaam-E-Qalandar Festival in Pakistan Amen Jaffer

A Drama of Saintly Devotion Performing Ecstasy and Status at the Shaam-e-Qalandar Festival in Pakistan Amen Jaffer Figure 1. Dancing the dhama\l in Sehwan in front of Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb, 7 February 2011. (Photo by Saad Hassan Khan) On the evening of 16 February 2017, the dhamal\ 1 ritual at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan, Pakistan, was tragically cut short when a powerful bomb ripped through a crowd of devotees, killing 83 and injuring hundreds (Khan and Akbar 2017).2 Seven years prior, in January 2010, I was witness to another dhama\l performance in the same courtyard of this 13th- century Sufi saint’s shrine (fig. 2). On that evening, the courtyard, which faces Qalandar’s tomb, 1. Dhama\l is a ritualized expression of love, desire, and connection with a saint as well as a celebration of the saint’s powers and miracles. It can take the form of dance or music. For treatments of the ritual sensibilities of this genre see Frembgen (2012) and Abbas (2002:33–35). For an analysis of its musical form and style see Wolf (2006). 2. Sehwan is a small city in the southeast province of Sindh that is best known as the site for Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb and shrine. TDR: The Drama Review 62:4 (T240) Winter 2018. ©2018 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 23 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram_a_00791 by guest on 24 September 2021 was also crowded with human bodies — but those bodies were very much alive. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-For-Tat Violence

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Paper Series Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence Hassan Abbas September 22, 2010 1 2 Preface As the first decade of the 21st century nears its end, issues surrounding militancy among the Shi‛a community in the Shi‛a heartland and beyond continue to occupy scholars and policymakers. During the past year, Iran has continued its efforts to extend its influence abroad by strengthening strategic ties with key players in international affairs, including Brazil and Turkey. Iran also continues to defy the international community through its tenacious pursuit of a nuclear program. The Lebanese Shi‛a militant group Hizballah, meanwhile, persists in its efforts to expand its regional role while stockpiling ever more advanced weapons. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi‛a has escalated in places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bahrain, and not least, Pakistan. As a hotbed of violent extremism, Pakistan, along with its Afghan neighbor, has lately received unprecedented amounts of attention among academics and policymakers alike. While the vast majority of contemporary analysis on Pakistan focuses on Sunni extremist groups such as the Pakistani Taliban or the Haqqani Network—arguably the main threat to domestic and regional security emanating from within Pakistan’s border—sectarian tensions in this country have attracted relatively little scholarship to date. Mindful that activities involving Shi‛i state and non-state actors have the potential to affect U.S. national security interests, the Combating Terrorism Center is therefore proud to release this latest installment of its Occasional Paper Series, Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence, by Dr. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Shah Hussain - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Shah Hussain - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Shah Hussain(1538–1599) Shah Hussain was a Punjabi Sufi poet who is regarded as a Sufi saint. He was the son of Sheikh Usman, a weaver, and belonged to the Dhudha clan of Rajputs. He was born in Lahore (present-day Pakistan). He is considered a pioneer of the Kafi form of Punjabi poetry. Shah Hussain's love for a Brahmin boy called "Madho" or "Madho Lal" is famous, and they are often referred to as a single person with the composite name of "Madho Lal Hussain". Madho's tomb lies next to Hussain's in the shrine. His tomb and shrine lies in Baghbanpura, adjacent to the Shalimar Gardens. His Urs (annual death anniversary) is celebrated at his shrine every year during the "Mela Chiraghan" ("Festival of Lights"). <b>Kafis of Shah Hussain</b> Hussain's poetry consists entirely of short poems known as Kafis. A typical Hussain Kafi contains a refrain and some rhymed lines. The number of rhymed lines is usually between four and ten. Only occasionally is a longer form adopted. Hussain's Kafis are also composed for, and have been set to, music deriving from Punjabi folk music. Many of his Kafis are part of the traditional Qawwali repertoire. His poems have been performed as songs by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Parveen and Noor Jehan, among others. Here are three examples, which draw on the love story of Heer Ranjha: "Ni Mai menoon Khedeyan di gal naa aakh Ranjhan mera, main Ranjhan di, Khedeyan noon koodi jhak Lok janey Heer kamli hoi, Heeray da var chak" "Do not talk of the Khedas to me, mother. -

Newsletter 3

MI French Interdisciplinary Mission in Sindh FS Edito The first half of the year 2009 was very busy for several reasons. The study group “History and Sufism in the Valley of the Indus” organized a one-day conference in January on Plurality of sources and interdisciplinary approach: a case study of Sehwan Sharif in Sindh. It was attended by senior scholars such as 9 Claude Markovits (CNRS-CEIAS) or Monique Kervran (CNRS), as well as doctoral students such as Annabelle Collinet and Johanna Blayac, and also 0 “post-docs” such as Frédérique Pagani (p. 4-5). The conference was also attended by Sindhis from the very small community settled in Paris. 0 In the same period, two professors working on Sufism in Pakistan were invited by the EHESS. Pnina Werbner, professor of Anthropology at Keele University, was 2 invited by IISMM, an institute centred on the Muslim world and affiliated to r EHESS. Professor Werbner delivered conferences on topics related to Sufism, e and she also headed a workshop for Ph.D. students. She wrote a seminal paper on Transnationalism and Regional Cults: The Dialectics of Sufism in the b Plurivocal Muslim World (p. 6-7) which will be put online on the forthcoming MIFS website. Professor Richard K. Wolf, professor of Ethnomusicology at Harvard University, was invited in May by the EHESS, by Marie-Claude Mahias (CNRS-CEIAS). He tem delivered four lectures, the first one devoted to Nizami Sufism in Karachi and Delhi. Professor Wolf gave a talk at the study group “History and Sufism in the p Valley of the Indus” on “Music in Shrine Sufism of Pakistan” (CEIAS, 28 May 2009). -

Spiritual Rituals at Sufi Shrines in Punjab: a Study of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif Vol

Global Regional Review (GRR) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/grr.2019(IV-I).23 Spiritual Rituals at Sufi Shrines in Punjab: A Study of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif Vol. IV, No. I (Winter 2019) | Page: 209 ‒ 214 | DOI: 10.31703/grr.2019(IV-I).23 p- ISSN: 2616-955X | e-ISSN: 2663-7030 | ISSN-L: 2616-955X Abdul Qadir Mushtaq* Muhammad Shabbir† Zil-e-Huma Rafique‡ This research narrates Sufi institution’s influence on the religious, political and cultural system. The masses Abstract frequently visit Sufi shrines and perform different rituals. The shrines of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi of Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif have been taken as case study due to their religious importance. It is a common perception that people practice religion according to their cultural requirements and this paper deals rituals keeping in view cultural practices of the society. It has given new direction to the concept of “cultural dimensions of religious analysis” by Clifford Geertz who says “religion: as a cultural system” i.e. a system of symbols which synthesizes a people’s ethos and explain their words. Eaton and Gilmartin have presented same historical analysis of the shrines of Baba Farid, Taunsa Sharif and Jalalpur Sharif. This research is descriptive and analytical. Primary and secondary sources have been consulted. Key Words: Khanqah, Dargah, SajjadaNashin, Culture, Esoteric, Exoteric, Barakah, Introduction Sial Sharif is situated in Sargodha region (in the center of Sargodha- Jhang road). It is famous due to Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, a renowned Chishti Sufi.