Filmmakers' Biography Filming 'Shahbaz Qalandar': From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ultimate Dimension of Life’ During His(RA) Lifetime

ABOUT THE BOOK This book unveils the glory and marvellous reality of a spiritual and ascetic personality who followed a rare Sufi Order called ‘Malamatia’ (The Carrier of Blame). Being his(RA) chosen Waris and an ardent follower, the learned and blessed author of the book has narrated the sacred life style and concern of this exalted Sufi in such a profound style that a reader gets immersed in the mystic realities of spiritual life. This book reflects the true essence of the message of Islam and underscores the need for imbibing within us, a humane attitude of peace, amity, humility, compassion, characterized by selfless THE ULTIMATE and passionate love for the suffering humanity; disregarding all prejudices DIMENSION OF LIFE and bias relating to caste, creed, An English translation of the book ‘Qurb-e-Haq’ written on the colour, nationality or religion. Surely, ascetic life and spiritual contemplations of Hazrat Makhdoom the readers would get enlightened on Syed Safdar Ali Bukhari (RA), popularly known as Qalandar the purpose of creation of the Pak Baba Bukhari Kakian Wali Sarkar. His(RA) most devout mankind by The God Almighty, and follower Mr Syed Shakir Uzair who was fondly called by which had been the point of focus and Qalandar Pak(RA) as ‘Syed Baba’ has authored the book. He has been an all-time enthusiast and zealous adorer of Qalandar objective of the Holy Prophet Pak(RA), as well as an accomplished and acclaimed senior Muhammad PBUH. It touches the Producer & Director of PTV. In his illustrious career spanning most pertinent subject in the current over four decades, he produced and directed many famous PTV times marred by hatred, greed, lust, Plays, Drama Serials and Programs including the breathtaking despondency, affliction, destruction, and amazing program ‘Al-Rehman’ and the magnificient ‘Qaseeda Burda Sharif’. -

New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab

Asia Society and CaravanSerai Present New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab Saturday, April 28, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 2 hours with no intermission New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan Performers Arooj Afab lead vocals Bhrigu Sahni acoustic guitar Jorn Bielfeldt percussion Arif Lohar lead vocals/chimta Qamar Abbas dholak Waqas Ali guitar Allah Ditta alghoza Shehzad Azim Ul Hassan dhol Shahid Kamal keyboard Nadeem Ul Hassan percussion/vocals Fozia vocals AROOJ AFTAB Arooj Aftab is a rising Pakistani-American vocalist who interprets mystcal Sufi poems and contemporizes the semi-classical musical traditions of Pakistan and India. Her music is reflective of thumri, a secular South Asian musical style colored by intricate ornamentation and romantic lyrics of love, loss, and longing. Arooj Aftab restyles the traditional music of her heritage for a sound that is minimalistic, contemplative, and delicate—a sound that she calls ―indigenous soul.‖ Accompanying her on guitar is Boston-based Bhrigu Sahni, a frequent collaborator, originally from India, and Jorn Bielfeldt on percussion. Arooj Aftab: vocals Bhrigu Sahni: guitar Jorn Bielfeldt: percussion Semi Classical Music This genre, classified in Pakistan and North India as light classical vocal music. Thumri and ghazal forms are at the core of the genre. Its primary theme is romantic — persuasive wooing, painful jealousy aroused by a philandering lover, pangs of separation, the ache of remembered pleasures, sweet anticipation of reunion, joyful union. Rooted in a sophisticated civilization that drew no line between eroticism and spirituality, this genre asserts a strong feminine identity in folk poetry laden with unabashed sensuality. -

A Drama of Saintly Devotion Performing Ecstasy and Status at the Shaam-E-Qalandar Festival in Pakistan Amen Jaffer

A Drama of Saintly Devotion Performing Ecstasy and Status at the Shaam-e-Qalandar Festival in Pakistan Amen Jaffer Figure 1. Dancing the dhama\l in Sehwan in front of Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb, 7 February 2011. (Photo by Saad Hassan Khan) On the evening of 16 February 2017, the dhamal\ 1 ritual at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan, Pakistan, was tragically cut short when a powerful bomb ripped through a crowd of devotees, killing 83 and injuring hundreds (Khan and Akbar 2017).2 Seven years prior, in January 2010, I was witness to another dhama\l performance in the same courtyard of this 13th- century Sufi saint’s shrine (fig. 2). On that evening, the courtyard, which faces Qalandar’s tomb, 1. Dhama\l is a ritualized expression of love, desire, and connection with a saint as well as a celebration of the saint’s powers and miracles. It can take the form of dance or music. For treatments of the ritual sensibilities of this genre see Frembgen (2012) and Abbas (2002:33–35). For an analysis of its musical form and style see Wolf (2006). 2. Sehwan is a small city in the southeast province of Sindh that is best known as the site for Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb and shrine. TDR: The Drama Review 62:4 (T240) Winter 2018. ©2018 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 23 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram_a_00791 by guest on 24 September 2021 was also crowded with human bodies — but those bodies were very much alive. -

Budget Execution Report 2Nd QUARTER 2020-21

Budget Execution Report 2nd QUARTER 2020-21 31th December, 2020 Government of Sindh Finance Department Table of contents: Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Table 1 Interim Fiscal Statement .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Table 2 Revenue by Object .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 3 Revenue by Department........................................................................................................................................... 7 Table 4 Expenditure by Department .................................................................................................................................... 9 Table 5 Recurrent Expenditure by Department, Grant and Object ............................................................................... 20 Table 6 Provincial ADP by Sector and Sub-sector .......................................................................................................... 41 Table 7 Development Expenditure by Sector, Subsector and Scheme ....................................................................... 42 Table 8 Current Capital Expenditure ............................................................................................................................... -

Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No

FINAL REPORT Mid-Term Evaluation /' " / " kku / Kondioro k I;sDDHH1 (Koo1,, * Nowbshoh On$ Hyderobcd Bulei Pt.ochi 7 godin Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No. 391-0480 Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development Islamabad, Pakistan IOC PDC-0249-1-00-0019-00 * Delivery Order No. 23 prepared by DE LEUWx CATHER INTERNATIONAL LIMITED May 26, 1993 Table of Contents Section Pafle Title Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables and Figures iv List of Abbieviations, Acronyms vi Basic Project Identification Data Sheet ix AID Evaluation Summary x Chapter 1 - Introduction 1-1 Chapter 2 - Background 2-1 Chapter 3 - Road Maintenance 3-1 Chapter 4 - Road Rehabilitation 4-1 Chapter 5 - Training Programs 5-1 Chapter 6 - District Revenue Sources 6-1 Appendices: - A. Work Plan for Mid-term Evaluation A-1 - B. Principal Officers Interviewed B-1 - C. Bibliography of Documents C-1 - D. Comparison of Resources and Outputs for Maintenance of District Roads in Sindh D-1 - E. Paved Road System Inventories: 6/89 & 4/93 E-1 - F. Cost Benefit Evaluations - Districts F-1 - ii Appendices (cont'd.): - G. "RRM" Road Rehabilitation Projects in SINDH PROVINCE: F.Y.'s 1989-90; 1991-92; 1992-93 G-1 - H. Proposed Training Schedule for Initial Phase of CCSC Contract (1989 - 1991) H-1 - 1. Maintenance Manual for District Roads in Sindh - (Revised) August 1992 I-1 - J. Model Maintenance Contract for District Roads in Sindh - August 1992 J-1 - K. Sindh Local Government and Rural Development Academy (SLGRDA) - Tandojam K-1 - L. -

PMD # Amount Date Name of Sponsors Amount Date Name of Scheme Cost Expenditure Savings % Utilization 1 357 100 9/25/2012 Dr

PM Directives Funds Released Sr. # Executing Agency Detail of Scheme Approved / Executed Under PMDs Financial Progress Name of PMD # Amount Date Amount Date Name of Scheme Cost Expenditure Savings sponsors % Utilization 1 402 200 10/16/2012 Dr. Fahmida Highway Division Badin 50 10/30/2012 Construction of Golarchi by pass road 289.864 187.545 0 64.7 Urban water supply scheme Shaheed Fazal 67.3 2 221 50 9/17/2012 Dr. Fahmida XEN PHE Division Badin 200 12/17/2012 90.127 60.652 14.348 Mirza, MNA Rahu Golarchi 50.6 Urban drainage Scheme Shaheed Fazal Rahu 107.85 54.58 10.42 Improvent & extention of Rural water supply 38.9 15.367 5.984 9.383 scheme Lawari Sharif 3 785 50 1/8/2013 Ghulam Ali DG Rural Development Department 50 2/14/2013 5.3 Construction of CC block in Mosque Qadir 4 0.21 3.79 Nizamani, Bux Colony District Badin MNA Construction of CC block at village Andhani 5.3 4 0.21 3.79 Nizamani district Badin Construction of CC block at village jaffar khan 100.0 4 4 0 chandio Reconditioning of metallic road Dargha 53.7 4 2.148 1.852 Jumman shah Construction of metallic road for Dargha 55.0 1.187 0.653 0.534 bukhair to zafarabad Construction of metallic road for village Kazi 49.2 10.377 5.102 5.275 Ibrahim 52.3 At village Dewani faqeer to Ghulam shah road 2.505 1.311 1.194 Village Pir Bux chandio 1.398 1.387 0.011 99.2 In village Ali Akber Paryal 1.398 1.398 0 100.0 Village Allahdino jamali 1.398 1.398 0 100.0 Village Urs Rahimoon 1.398 1.18 0.218 84.4 Village haji allah warayo 1.398 1.179 0.219 84.3 Village allahdino Notkani 1.398 1.398 -

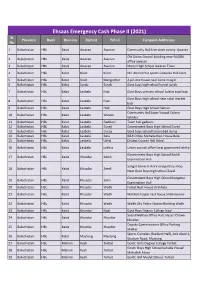

UPDATED CAMPSITES LIST for EECP PHASE-2.Xlsx

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Phase II (2021) Sr. Province Bank Division Distrcit Tehsil Campsite Addresses No. 1 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Community Hall Live stock colony Awaran Old Union Council building near NADRA 2 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran office awaran 3 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Model High School Awaran Town 4 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Kalat Mir Ahmed Yar sports Complex Hall kalat 5 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Mangochar A private house near Jame masjid 6 Balochistan HBL Kalat Surab Surab Govt boys high school hostel surab 7 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys primary school Adalat road hub Govt Boys high school near sabzi market 8 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub hub 9 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys High School Sakran Community Hall Jaam Yousuf Colony 10 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Winder Winder 11 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Gaddani Town hall gaddani 12 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Government Boys High School Dureji 13 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Govt boys school hasanabad dureji 14 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Bela B&R Office Mohalla Rest House Bela 15 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Uthal District Council Hall Uthal 16 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Lakhra Union council office local goverment lakhra Government Boys High School Karkh 17 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Karkh Examination Hall Sangat General store and poltary shop 18 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zeedi Near Govt Boys high school Zeedi Government Boys High School Norgama 19 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zehri Examination Hall 20 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Forest Rest House Drakhala 21 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Mohbat Faqeer rest house Shahnoorani 22 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Wadh City Police Station Building Wadh 23 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Naal Govt Boys Degree College Naal Social Welfare Office Hall, Hazari Chowk 24 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Khuzdar khuzdar. -

Sufism in South Punjab, Pakistan: from Kingdom to Democracy

132 Journal of Peace, Development and Communication Volume 05, Issue 2, April-June 2021 pISSN: 2663-7898, eISSN: 2663-7901 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.36968/JPDC-V05-I02-12 Homepage: https://pdfpk.net/pdf/ Email: [email protected] Article: Sufism in South Punjab, Pakistan: From kingdom to democracy Dr. Muzammil Saeed Assistant Professor, Department of Media and Communication, University of Author(s): Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Maria Naeem Lecturer, Department of Media and Communication, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Published: 30th June 2021 Publisher Journal of Peace, Development and Communication (JPDC) Information: Saeed, M., & Naeem, M. (2021). Sufism in South Punjab, Pakistan: From kingdom to To Cite this democracy. Journal of Peace, Development and Communication, 05(02), 132–142. Article: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36968/JPDC-V05-I02-12. Dr. Muzammil Saeed is serving as Assistant Professor at Department of Media and Communication, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Corresponding Author’s Email: [email protected] Author(s) Note: Maria Naeem is serving as Lecturer at Department of Media and Communication, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] From kingdom to democracy 133 Abstract Sufism, the spiritual facet of Islam, emerged in the very early days of Islam as a self- awareness practice and to keep distance from kingship. However, this institution prospered in the times of Muslim rulers and Kings and provided a concrete foundation to seekers for spiritual knowledge and intellectual debate. Sufism in South Punjab also has an impressive history of religious, spiritual, social, and political achievements during Muslim dynasties. -

SUFIS and THEIR CONTRIBUTION to the CULTURAL LIFF of MEDIEVAL ASSAM in 16-17"' CENTURY Fttasfter of ^Hilojiopl)?

SUFIS AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE CULTURAL LIFF OF MEDIEVAL ASSAM IN 16-17"' CENTURY '•"^•,. DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fttasfter of ^hilojiopl)? ' \ , ^ IN . ,< HISTORY V \ . I V 5: - • BY NAHIDA MUMTAZ ' Under the Supervision of DR. MOHD. PARVEZ CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2010 DS4202 JUL 2015 22 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh-202 002 Dr. Mohd. Parwez Dated: June 9, 2010 Reader To Whom It May Concern This is to certify that the dissertation entitled "Sufis and their Contribution to the Cultural Life of Medieval Assam in 16-17^^ Century" is the original work of Ms. Nahida Muxntaz completed under my supervision. The dissertation is suitable for submission and award of degree of Master of Philosophy in History. (Dr. MoMy Parwez) Supervisor Telephones: (0571) 2703146; Fax No.: (0571) 2703146; Internal: 1480 and 1482 Dedicated To My Parents Acknowledgements I-11 Abbreviations iii Introduction 1-09 CHAPTER-I: Origin and Development of Sufism in India 10 - 31 CHAPTER-II: Sufism in Eastern India 32-45 CHAPTER-in: Assam: Evolution of Polity 46-70 CHAPTER-IV: Sufis in Assam 71-94 CHAPTER-V: Sufis Influence in Assam: 95 -109 Evolution of Composite Culture Conclusion 110-111 Bibliography IV - VlU ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of my teachers and friends from whose help and advice I have benefited. It is a rare obligation to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Mohd. -

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated List of Campsites and Bank Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments Campsites Ehsaas Emergency Cash List of campsites for biometrically enabled payments in all 4 provinces including GB, AJK and Islamabad AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR SR# District Name Tehsil Campsite 1 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 2 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 3 Bagh Bagh Boys inter college Rera Dhulli Bagh 4 Bagh Harighal BISP Tehsil Office Harigal 5 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 6 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 7 Hattain Hattian Girls Degree Collage Hattain 8 Hattain Hattian Boys High School Chakothi 9 Hattain Chakar Boys Middle School Chakar 10 Hattain Leepa Girls Degree Collage Leepa (Nakot) 11 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 12 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 13 Haveli Khurshidabad Boys Inter Collage Khurshidabad 14 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Post Graduate College Kotli 15 Kotli Kotli Inter Science College Gulhar 16 Kotli Kotli Govt. Girls High School No. 02 Kotli 17 Kotli Kotli Boys Pilot High School Kotli 18 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Middle School Tatta Pani 19 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Girls High School Sehnsa 20 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Boys High School Sehnsa 21 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Govt. Boys Degree College Fatehpur Thakyala 22 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Local Govt. Office 23 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Charhoi 24 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Middle School Gulpur 25 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Higher Secondary School Rajdhani 26 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Naar 27 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Boys High School Khuiratta 28 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Girls High School Khuiratta 29 Bhimber Bhimber Govt. -

The Sticky Shia Sonics of Sehwan by Omar Kasmani

Audible Spectres: The Sticky Shia Sonics of Sehwan by Omar Kasmani This text draws on three inter-related sound recordings from two affiliated saints’ shrines in Sehwan, a renowned place of pilgrimage on the banks of the river Indus in Pakistan[1]. The shrine of Bodlo, though much smaller, is second only to that of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, the principal saint of Sehwan, and of whom Bodlo is the penultimate disciple. The two sites are materially and © Omar Kasmani discursively conversant with each other amid flows of legend, ritual, relics and people, also sound. The sources I discuss here are sonic- lyrical offerings[2] performed by pilgrims facing saints’ tombs at the two shrines. Though of varied emotional tenors and composed in different languages, these offerings move pilgrims and saints alike evoke related Islamic holy figures and point to shared scenes and spheres of affect. The first one – recorded at the shrine of Bodlo in 2013 – documents a pilgrim’s lyrical tribute to Hussain, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad martyred at the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE. Hussain remains a key figure of devotion for Muslims, especially the Shia in Pakistan. The Punjabi song "like Allah listens, listens Hussain” recounts his miraculous attributes and projects him as a figure of petition, one who is attentive and ever-listening. To the childless, he grants children, the man sings, and to the needy, a patron, their saviour. Hussain is as much admired for his willingness to battle against odds in these verses as he is remembered for his ultimate act of sacrifice. -

PERSONS • of the YEAR • Muslimthe 500 the WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2018 •

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • MuslimThe 500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2018 • MuslimThe 500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2018 • C The Muslim 500: 2018 Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer The World’s 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2018 Deputy Chief Editor: Ms Farah El-Sharif ISBN: 978-9957-635-14-5 Contributing Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary Editor-at-Large: Mr Aftab Ahmed Jordan National Library Deposit No: 2017/10/5597 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour © 2017 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, PO BOX 950361 Zeinab Asfour, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN http://www.rissc.jo Consultant: Simon Hart All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced Typeset by: M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanic, including photocopying or recording or by any in- formation storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courtesy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi • Contents • page 1 Introduction 5 Persons of the Year—2018 7 Influence and The Muslim 500 9 The House of Islam 21 The Top 50 89 Honourable Mentions 97 The 450 Lists 99 Scholarly