The Name of the Island of Annet, Isles of Scilly, Cornwall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking in the Isles of Scilly

WALKING IN THE ISLES OF SCILLY 11 WALKS AND 4 BOAT TRIPS EXPLORING THE BEST OF THE ISLANDS by Paddy Dillon JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Paddy Dillon 2021 CONTENTS Fifth edition 2021 ISBN 978 1 78631 104 7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................5 Location ..........................................................6 Fourth edition 2015 Geology ..........................................................6 Third edition 2009 Ancient history .....................................................7 Second edition 2006 Later history .......................................................9 First edition 2000 Recent history .....................................................10 Getting to the Isles of Scilly ..........................................11 Getting around the Isles of Scilly ......................................13 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper on behalf of Latitude Press. Boat trips ........................................................15 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Tourist information and accommodation ................................15 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Maps of the Isles of Scilly ............................................17 The walks ........................................................18 Guided walks .....................................................19 Island flowers .....................................................20 © Crown copyright -

Sabrina Times July 2007 Editorial Library This Issue Is a Short One and It's Late

E 17 July 2007 Severnside Branch SSaabbrriinnaa TTiimmeess Branch Organiser's Bit I have just reviewed my last piece for the newsletter and find I made a comment about how the weather would surely be better for our May fieldtrip. How wrong I was! Although the day before had been lovely, Sunday 13th May was very overcast and wet. The Cat's Back was not visible through the cloud but I was impressed by the number of members who turned out in such weather. It was great to see you all. Also, well done and thank you to Duncan who was able to offer us an alternative, lower route, avoiding the cloud if not the rain, and still filled the day with interesting Ever wonder where the exposures. “Sabrina” name comes Our trip to Flat Holm in June was fully booked; from? Here's your answer. as is the week’s trip to Kindrogan in July. Unlike One of a series of carved the Cat's Back trip, the weather for Flat Holm oak statues near the Old was good. It was an excellent day out, and I'd Railway Station, Tintern, like to thank Chris Lee for guiding us. it is dedicated to the Jan and Linda are running a shoestring trip to legend of the Celtic the Sierras in Central Spain in September. goddess, whose latinised There are still spaces on this. In addition to the name is Sabrina. The geology there are many medieval towns in the inset is of the signboard area to explore; not to mention Madrid. -

Natural Phonetic Tendencies and Social Meaning: Exploring the Allophonic Raising Split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly

This is a repository copy of Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133952/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, E.F. and Carter, P. (2018) Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. Language Variation and Change, 30 (3). pp. 337-360. ISSN 0954-3945 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157 This article has been published in a revised form in Language Variation and Change [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Title: Natural phonetic tendencies -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Flat Holm Island

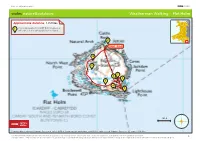

bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles 1 This walk begins in Cardiff Bay where you will catch the boat across to the island. 2 Start / End 10 9 7 8 6 3 4 5 N 500 ft W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to the TV programme only. Routes and conditions may have changed since the programme was made. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check weather conditions before heading out. 1 bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles A race against the tide to look at wartime relics and a stunning lighthouse on this beautiful island in the Bristol Channel. 1. The Cardiff Bay Barrage 4. Flat Holm Lighthouse This is where you will catch the boat to the The first light on the island was a simple island. The Barrage lies across the mouth brazier mounted on a wooden frame, which of Cardiff Bay between Queen Alexandra stood on the high eastern part of the island. Dock and Penarth Head and was one of The construction of a tower lighthouse with the largest civil engineering projects in lantern light was finished in 1737. Europe during the 1990s. Today it’s solar powered and the light from its three 100 watt bulbs can be seen up to 16 miles away. -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Existing Use of Pendrethen Quarry 2003 to 2015

Mulciber Ltd Lunnon Farm, St Mary's Isles of Scilly, TR21 0NZ Diccon Rogers Tel: 0845 5143123 / 07785 520274 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Vat Reg No 900 9655 28 Existing Use of Pendrethen Quarry 2003 to 2015 Quarter (Q) dates: Q1 – January 1st – March 31st ; Q2 –April; 1st – June 30th; Q3 –July 1st – September 30th; Q4 – October 1st –December 31st. Year Date Activities/Key Information Mulciber Invoice No. or other Evidence Please note: this is a table of activities based principally on issued and paid invoices. For every sale of recycled aggregates and materials from Pendrethen Quarry, there will also be extensive processing works ongoing throughout to produce the material. 2003 Q2 – Deposit of inert C&D waste in pit of quarry for future recycling by DoC Photographs Q3 2004 Importation to site, stockpiling, processing, exporting to local markets throughout the year Q1 28th January Chestnut paling fence to be erected around Pendrethen Quarry by Duchy Contractors, working alongside Mulciber 30th March Clearance work begins by Mulciber Work & production records Q2 4th June Scrap metal clearance and recycling at Quarry by Mulciber Ltd 143 & 145 onwards First supplies of local recycled ram and sand from Quarry from Mulciber Ltd, recovered from old stockpiles and cleaned, graded and supplied for new building at St Mary’s Riding Centre. 154 Q3 Clearance and recycling operations continue Q4 November Crusher unit salvaged from redundant quarry plant, refurbished and converted to mobile crusher by Mulciber Ltd. On Correspondence hire around St Mary’s, including at Star Castle Hotel providing crushing and recycling services. -

To Be Opened on Receipt AS GCE APPLIED TRAVEL and TOURISM G720/01/CS Introducing Travel and Tourism

To be opened on receipt AS GCE APPLIED TRAVEL AND TOURISM G720/01/CS Introducing Travel and Tourism PRE-RELEASE CASE STUDY JUNE 2014 *1106235075* INSTRUCTIONS TO TEACHERS • This Case Study must be opened and given to candidates on receipt. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • You must make yourself familiar with the Case Study before you sit the examination. • You must not take notes into the examination. • A clean copy of the Case Study will be given to you with the Question Paper. • This document consists of 16 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. © OCR 2014 [M/102/8242] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (CW/SW) 72956/5 Turn over 2 The following stimulus material has been adapted from published sources. It is correct at the time of publication, and all statistics are taken directly from the published material. Document 1 Tourism on the Isles of Scilly 85% of the Isles of Scilly’s economy is tourism-related with 37% of the employees on the islands working in the tourism sector. Tourism attracts about 90 000–100 000 visitors per year, around 50 times the resident population of the islands. Repeat visitors account for 65%–75% of tourists, the majority of whom are over 45 years old. The main attractions for visitors are: • walking (95%) • inter-island boat trips (85%) • eating out (80%) • wildlife/bird-watching (60%) • arts/crafts (30%) • sailing/water sports (20%). 64% of visitors choose the Isles of Scilly as their main holiday; of these 48% stay 5–7 days, 9% for 8–10 days and 25% for 11 days or more. -

Isles of Scilly Information Sheet

Isles of Scilly information sheet Welcome to the Isles of Scilly... 28 miles south west of Land’s End in clear, blue Atlantic water, fabled in distant legend to be indeed the last remnant of the magical land of Lyonesse, these beautiful islands of low hills exude a timeless peace and natural tranquillity. But don’t think timeless islands need to be behind the times. All the inhabited islands offer excellent amenities, safe sandy beaches, pubs and opportunities for outdoor sport. There are many sites of historical interest throughout the islands. The bird watching and scuba diving are renowned. In spring the early flowering of daffodils and narcissi carpet the islands’ small fields and in the autumn there is the opportunity to spot rare and wonderful birds as they make their way to the warmer climes of southern Europe or have been blown across from America. There are good communications. Aeroplane and ferry services connect the islands to the mainland and regular launch services, seven days a week, link the islands to each other. The islands also enjoy superfast broadband and 4G mobile data coverage. There is also a fast postal service with Royal Mail deliveries often reaching the islands the next day. Other deliveries through couriers reach the islands with a short delay following transport on the regular freight ship. So, welcome to unique Scilly. Enjoy the peace and the tranquillity of one of the world’s most beautiful archipelagos. Life on the Islands... the Isles of Scilly are much more than a group of beautiful islands complete with glorious beaches, wonderful views, magnificent seascape and abundant wildlife. -

Isles of Scilly, United Kingdom

Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery. 2019, 3(4): 393-395 © 2019 GCdataPR DOI:10.3974/geodp.2019.04.13 Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository www.geodoi.ac.cn Global Change Data Encyclopedia Isles of Scilly, United Kingdom 1 1* 1 2 Zhang, Y. H. Liu, C. Shi, R. X. Chen, L. J. 1. Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; 2. National Geomatics Center of China, Beijing 100830, China Keywords: Isles of Scilly; England; Cornwall; data encyclopedia The Isles of Scilly, also called Scilly Isles, is lying southwest of Cornwall, England, 40 to 58 km off Land’s End. It’s geo-location is 49°51′48″N–49°58′ 58″N, 6°26′45″W – 6°14′34″W [1– 5] (Figures 1, 2). There are 265 islands and islets in the Isles of Scilly, but only five of the islands are inhabited, St. Mary’s Island, Tresco Island, St Martin’s Island, Bryher Island and St. Agnes-Gugh Island. The Bryher Figure 1 Map of the Isles of Scilly (.shp format) Island (49°57′12″N, 6°21′22″W) is the smallest inhabited island with the area of 1.61 km2 and the coastline of 13.32 km. Bishop Rock (49°52′23″N, 6°26′44″W), with an area of 2,447 m2, is located at the western end of the Isles of Scilly, with a notable lighthouse of civil engineer- ing built in November, 1858[6]. The big- gest island is the St. Mary’s Island with 2 the area of 7.37 km and the coastline of 23.48 km. -

Island Futures: a Strategic Economic Plan for the Isles of Scilly (2014)

Island Futures A strategic economic plan for the Isles of Scilly May 2014 A thriving, vibrant community rooted in nature, ready for change and excited about the future Contents Page Introduction 3 Context 4 Risk and Realism 5 Evidence 6 Vision for the Future 11 Aims and Objectives 12 Essential Conditions 14 Objectives 18 Transport Tourism Branding Diversification Collaboration Self-sufficiency Leadership and Delivery 27 References and Consultation 29 ! Annex 1. KEY ACTIONS Annex 2. BUSINESS SURVEY ! Linked documents: HOUSING GROWTH PLAN INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN !! "2 !!!!! Island Futures - a strategic economic plan Introduction The Isles of Scilly, 28 miles off the coast of Lands End, are remarkably beautiful and wild islands that are home to entrepreneurial and resilient communities. With a long history, an independent spirit and rich wildlife, Scilly has attracted adventurers, settlers and holidaymakers for centuries. ! In January 2014, Ash Futures, together with Three Dragons, was asked to produce a Strategic Economic Plan for the Isles of Scilly, supported by Housing and Infrastructure Plans. These plans stand alone but are linked. They look at the key priorities for strengthening and diversifying the economy of the islands over the long term, and how these priorities might be delivered. The work has been supported by the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership. We have met with a range of stakeholders and businesses on the islands and key partners off the islands. We have read the many reports, research documents and strategies that have been produced for the Council over the past ten years. These Plans, build on those discussions and the previous reports, setting out clear proposals for housing, I’ve lived here for four years now infrastructure and economic development. -

The Development of Key Characteristics of Welsh Island Cultural Identity and Sustainable Tourism in Wales

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 3, No 1, (2017), pp. 23-39 Copyright © 2017 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.192842 THE DEVELOPMENT OF KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF WELSH ISLAND CULTURAL IDENTITY AND SUSTAINABLE TOURISM IN WALES Brychan Thomas, Simon Thomas and Lisa Powell Business School, University of South Wales Received: 24/10/2016 Accepted: 20/12/2016 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper considers the development of key characteristics of Welsh island culture and sustainable tourism in Wales. In recent years tourism has become a significant industry within the Principality of Wales and has been influenced by changing conditions and the need to attract visitors from the global market. To enable an analysis of the importance of Welsh island culture a number of research methods have been used, including consideration of secondary data, to assess the development of tourism, a case study analysis of a sample of Welsh islands, and an investigation of cultural tourism. The research has been undertaken in three distinct stages. The first stage assessed tourism in Wales and the role of cultural tourism and the islands off Wales. It draws primarily on existing research and secondary data sources. The second stage considered the role of Welsh island culture taking into consideration six case study islands (three with current populations and three mainly unpopulated) and their physical characteristics, cultural aspects and tourism. The third stage examined the nature and importance of island culture in terms of sustainable tourism in Wales. This has involved both internal (island) and external (national and international) influences.