The Earliest Known Sailing Directions in English Ward, Robin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sabrina Times July 2007 Editorial Library This Issue Is a Short One and It's Late

E 17 July 2007 Severnside Branch SSaabbrriinnaa TTiimmeess Branch Organiser's Bit I have just reviewed my last piece for the newsletter and find I made a comment about how the weather would surely be better for our May fieldtrip. How wrong I was! Although the day before had been lovely, Sunday 13th May was very overcast and wet. The Cat's Back was not visible through the cloud but I was impressed by the number of members who turned out in such weather. It was great to see you all. Also, well done and thank you to Duncan who was able to offer us an alternative, lower route, avoiding the cloud if not the rain, and still filled the day with interesting Ever wonder where the exposures. “Sabrina” name comes Our trip to Flat Holm in June was fully booked; from? Here's your answer. as is the week’s trip to Kindrogan in July. Unlike One of a series of carved the Cat's Back trip, the weather for Flat Holm oak statues near the Old was good. It was an excellent day out, and I'd Railway Station, Tintern, like to thank Chris Lee for guiding us. it is dedicated to the Jan and Linda are running a shoestring trip to legend of the Celtic the Sierras in Central Spain in September. goddess, whose latinised There are still spaces on this. In addition to the name is Sabrina. The geology there are many medieval towns in the inset is of the signboard area to explore; not to mention Madrid. -

Flat Holm Island

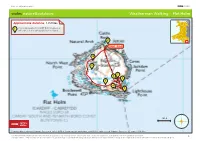

bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles 1 This walk begins in Cardiff Bay where you will catch the boat across to the island. 2 Start / End 10 9 7 8 6 3 4 5 N 500 ft W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to the TV programme only. Routes and conditions may have changed since the programme was made. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check weather conditions before heading out. 1 bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles A race against the tide to look at wartime relics and a stunning lighthouse on this beautiful island in the Bristol Channel. 1. The Cardiff Bay Barrage 4. Flat Holm Lighthouse This is where you will catch the boat to the The first light on the island was a simple island. The Barrage lies across the mouth brazier mounted on a wooden frame, which of Cardiff Bay between Queen Alexandra stood on the high eastern part of the island. Dock and Penarth Head and was one of The construction of a tower lighthouse with the largest civil engineering projects in lantern light was finished in 1737. Europe during the 1990s. Today it’s solar powered and the light from its three 100 watt bulbs can be seen up to 16 miles away. -

The Development of Key Characteristics of Welsh Island Cultural Identity and Sustainable Tourism in Wales

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 3, No 1, (2017), pp. 23-39 Copyright © 2017 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.192842 THE DEVELOPMENT OF KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF WELSH ISLAND CULTURAL IDENTITY AND SUSTAINABLE TOURISM IN WALES Brychan Thomas, Simon Thomas and Lisa Powell Business School, University of South Wales Received: 24/10/2016 Accepted: 20/12/2016 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper considers the development of key characteristics of Welsh island culture and sustainable tourism in Wales. In recent years tourism has become a significant industry within the Principality of Wales and has been influenced by changing conditions and the need to attract visitors from the global market. To enable an analysis of the importance of Welsh island culture a number of research methods have been used, including consideration of secondary data, to assess the development of tourism, a case study analysis of a sample of Welsh islands, and an investigation of cultural tourism. The research has been undertaken in three distinct stages. The first stage assessed tourism in Wales and the role of cultural tourism and the islands off Wales. It draws primarily on existing research and secondary data sources. The second stage considered the role of Welsh island culture taking into consideration six case study islands (three with current populations and three mainly unpopulated) and their physical characteristics, cultural aspects and tourism. The third stage examined the nature and importance of island culture in terms of sustainable tourism in Wales. This has involved both internal (island) and external (national and international) influences. -

ESC in WALES, United Kingdom Flat Holm Island Volunteer

ESC IN WALES, United Kingdom Flat Holm Island Volunteer Role Description: Trainee Assistant Warden March 2021 for 10 months Volunteers from Estonia, Germany, France, Spain, Czech Republic, Belgium and Austria are eligible to apply __________________________________________________________________ Host project Cardiff Council is a local authority employing approx. 15000 employees. Cardiff Harbour Authority is a department within Cardiff Council that manages Flat Holm Island. Flat Holm is a small island 5 miles off the Cardiff coast and is a Site of Special Scientific Interest, Local Nature Reserve, Historic site and visitor destination. Its main aim is to conserve the natural habitats, plants and wildlife, historic features and provide opportunities for people in its widest sense including volunteering and learning new skills. We welcome volunteers on our long term Voluntary Assistant Warden Scheme where training in heritage management, habitat management and nature conservation, wildlife monitoring/surveys and environmental education/visitor management is offered. The island welcomes day trippers to our visitor centre in the Victorian barracks (grey stone building in the photo) who are provided with guided tours and there is also dormitory accommodation, camping and a converted Lighthouse keeper’s cottage available for overnight stays for visitors which include individuals, families, youth groups, special interest groups etc who can get involved in activities such as conservation, retreats, education survival skills and more. Whilst on the Island, volunteers live in a converted World War 2 accommodation block during summer (white building shown in the above photo) and in the farmhouse dormitories during winter (photo on left). The island is also supported by a voluntary ‘Friends of’ group called the Flat Holm Society. -

Marine Protected Areas for the UK's Seabirds

Safeguarding Our Seabirds: Marine Protected Areas for the UK’s Seabirds 2 Marine Protected Areas for the UK’s seabirds Executive summary As an island nation, we have enjoyed This report is designed to capitalise the riches of the UK’s marine resources, on these opportunities by setting out but this has been at considerable cost the RSPB’s recommendations for the to marine wildlife. Now time is running next steps towards comprehensive out. Despite the many and increasing marine protection throughout UK seas. threats known to be facing our seas, We have identifi ed over 70 nearshore and the proven benefi ts of marine marine areas worthy of protection protected areas (MPAs), we have so far due to their importance at the UK managed to establish only a handful of level for breeding seabirds. This is an Razorbills. Andy Hay (rspb-images.com) protected areas in UK waters. To date important fi rst step towards identifying less than 0.001% of our sea area has a complete network to protect seabirds been fully protected from all damaging throughout UK waters, though it will activities. also be necessary to identify areas further offshore that birds might use The UK Government and the devolved for feeding purposes, as well as areas administrations have many and varied important to concentrations of wintering commitments to protecting the marine and migrating birds. environment, but we still lack suitable site protection legislation in the UK. The much needed work to identify and The UK Government is committed designate internationally important to introducing a Marine Bill in the life sites for seabirds must not be of this Parliament, and the Scottish overlooked, but the main focus of the Government has promised legislation recommendations presented here is for to cover its waters by 2010. -

Analysing Clipped Sea-Level Records for Harmonic Tidal Constituents

ANALYSING CLIPPED SEA-LEVEL RECORDS FOR HARMONIC TIDAL CONSTITUENTS by J.J. EVANS and D.T. PUGHUI Coastal sea-level measurements must sometimes be made at sites where the gauge dries out at low levels. By progressively removing the lower part of a tidal record, and analysing the remainder with the conventional least-squares criteria, we have obtained stable values of the principal constants until only half of the original range remained. This stability has implications for the definitions of tidal constants and of mean sea level in regions of very shallow water and drying banks. INTRODUCTION As part of a recent survey of tidal conditions in the Severn Estuary and Bristol Channel (Alcock and Pu g h ) [1], it was necessary to install a sea-level recorder on the island of Flat Holm, with a zero level 2.8 m above Lowest Astronomical Tide. The gauge therefore dried out for the lowest part of the large spring range (10.5 m) which occurs in the area. In order to compare the data from Flat Holm with those from contemporary bottom pressure records at Lavernock Point and Steep Holme, 4.0 km northwest and 5.0 km south of Flat Holm respectively, harmonic tidal analyses were made of the data at all three sites. ANALYSES Following the usual practice, harmonic constituents were determined by fitting the function : T(t) = Zo + iNHnfn COS (ant ~ g„ + V n + U„) (*) Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Bidston Observatory, Birkenhead, Merseyside, U.K. where Zo is mean sea level or pressure, H„ and g„ are the amplitude and phase of the constituent, 'Tr, is the constituent speed, and V,„ u„ and f„ are astronomical arguments (See, for example, M lrra y )[5], [6], The parameters were fitted subject to the conditions that ER2(t) is a minimum, where R(t) = 0(t) - T(t) and 0(0 is the observed level or pressure. -

CCC-News-March-2021 Web

NEWSLETTER Spring Portside 2021 Cabot Cruising Club I am sorry but once again you are receiving an e-mail only version of the newsletter. Whilst the Club remains closed it does not seem appropriate to warrant the printed version whilst the sites they are normally available from remain closed. Please feel free to forward it to anybody you think might like to know more about Cabot Cruising Club and the ‘John Sebastian’. I am sure by now all of us had hoped the situation would have improved, however we must just continue to be patient and sensible a bit longer, I know we all want to get back out on the water again as soon as possible. Hopefully we are at least approaching the time when we can start de-winterising and preparing our boats. So far it has certainly felt like a double whammy with us all being not only in lockdown but also In this issue: Page landlocked! Opening Comment 1 Circumstances have once again left me very short on Christmas Lights 2 CCC news due to the closure so I hope the interesting Commodore’s Message 2 but not necessarily Club related stories will suffice. Bristol Floating Harbour 3 The Committee are still meeting thanks to the use of Cabot News 4 Zoom and even I have managed to use this medium although I can’t say I like seeing my own representation A Very Shaggy Dog Story 4 on screen. I’m sure the software must purposely age Looking Back 5 the image in some way! Lightvessel News 6 Stay safe and hope to see you all again soon. -

Welsh Sea Kayaking Welsh

Front Cover - View from Porth Dinllaen Back Cover - Skerries Lighthouse Welsh Sea Kayaking Welsh Jim Krawiecki & Andy Biggs Welsh Sea Kayaking fifty great sea kayak voyages Welshfifty great Sea sea kayak Kayaking voyages From the Dee Estuary to the Bristol Channel, the Welsh coastline in all its varied guises provides a fantastic Jim playground for the sea kayaker. These select fifty journeys cover all of the interesting parts of the coast and provide & Krawiecki easy sheltered paddles, testing offshore trips for the adventurous and everything in between. Illustrated with superb colour photographs and useful maps throughout, this book is a practical guide to help you select Biggs Andy and plan trips. It will provide inspiration for future voyages and a souvenir of journeys undertaken. As well as providing essential information on where to start and finish, distances, times and tidal information, the book does much to stimulate and inform our interest in the environment we are passing through. It is full of facts and anecdotes about local history, geology, scenery, seabirds and sea mammals. 15 12 13 14 11 10 4 2 1 9 8 7 3 5 6 16 17 22 23 18 21 20 19 24 25 26 27 28 30 29 31 32 34 36 33 35 37 38 40 43 39 44 42 41 45 46 47 49 48 50 Welsh Sea Kayaking fifty great sea kayak voyages Jim Krawiecki & Andy Biggs Pesda Press www.pesdapress.com First published in Great Britain 2006 by Pesda Press Reprinted with minor updates 2009 Reprinted 2013 Tan y Coed Canol Ceunant Caernarfon Gwynedd LL55 4RN Wales Copyright © 2005 Jim Krawiecki and Andy Biggs ISBN 0-9547061-8-8 ISBN 13 9780954706180 The Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work. -

The Geology of the Severn Barrage Area

NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL Institute of Geological Sciences The geology of the Severn barrage area A report prepared by the Institute of Geological Sciences 621.49 for the Department of Energy 157 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL Institute of Geological Sciences SUNDERLAND POLYTECHNIC POLYTECHNIC LIBRARY 800K No .................~ 1. I : ...........4-'i .......:C.... 5r... -p"5 O{~ ACCESS NO .... .......... ............... DUE ~ RETURN ON. THE LAST DATE STAMPED IELCW The geology of the Severn barrage area "'f ,, ,., . - 8• C.; • 1'}J,.1 by G. W. Green and B. N. Fletcher • • O• • • • •' • • • o ,o • •' • •• ' ' • o"' ' ' o • • •" •o • o • ' •' ' • ~' •,• o •• • • • • • • o o • • 0•" 0• •' o ,o • • o "o • • • • • ,o o • o o oo ,o •o •• • • o o • o • • • ++ o " • ••I• • •• • o .................................... .. ... ····· ·· ··································· ....... , .. ;,, , ., ......................... ..... .. ... .............................................. ...... 1 ..... ... ...................................... .. SU N E 'L·I D POLYTiC, ~IC ........... ... ............. ... .... .......................... ........ .........., ..................... ...... ................ ' : Priestman Library,~ MSD 2211 Institute of Geological Sciences Ring Road Halton and 5 Princes Gate Leeds LSI5 8TQ London SW7 IQN A report prepared b y t he Institute of Geological Sciences for the Department of Energy May 1976 CONTENTS Page Onshore geology 1 Notes on succession 1 Notes on the structure 2 Offshore geology 2 Geological information along the line of the barrage 4 The Institute of Geological Sciences was formed by the Engineering geology notes 4 incorporation of the Geological Survey of Great Britain and the Museum of Practical Geology with Recommendations for additional offshore work 8 Overseas Geological Surveys and is a constituent body References 8 of the Natural Environment Research Council. ILL UST RATI ONS © NERC copyright 1977 Fig. 1. Bathymetry of the Severn Estuary between Lavernock Point and Weston- super-Mare 3 Fig. -

Weston Super Mare Or Ilfracombe Minehead 1730 Penarth 1500 Clevedon 1900 in Glorious Devon

Sailing from MINEHEAD Harbour Porlock Bay WEDNESDAY June 5 Leave 3.45pm back 4.45pm 2010 WEDNESDAY June 19 Leave 2.15pm back 3.15pm Great Days Out Fare: Cruise Porlock Bay £13 SC £11 aboard the famous Lundy Island THURSDAY June 13 Leave 10am back 8.30pm Fare: Visit Lundy Island £39 Paddle Steamer Waverley! Ilfracombe THURSDAY June 13 Leave 10am back 8.30pm Glorious Devon MONDAY June 17 Leave 1pm back 6.45pm Fare: Visit Ilfracombe £27 SC £25 Jun 17: Coach return from Ilfracombe SAILING Sailing from ILFRACOMBE Harbour June 5 until June 25 Lundy Island SUNDAYS June 9 & June 23 THURSDAY June 13 Leave 12.15 back 6.30pm Fare: Visit Lundy Island £35 Exmoor Coast SATURDAY June 15 Leave 2.30pm back 4.45pm Fare: Cruise Exmoor Coast £17 Atlantic Coast THURSDAY June 6 SATURDAY June 22 Leave 1.45pm back 3.15pm Fare: Cruise Atlantic Coast £15 WAVERLEY’s BRISTOL CHANNEL sailings in 2013 WEDNESDAY June 5 SUNDAYS FRIDAY June 14 TUESDAY June 18 Clevedon 1230 June 9 & 23 Porthcawl 1000 Clevedon 0930 Penarth 1400 Jun 9 : Lundy Church Service Ilfracombe 1130/1830 Penarth 1045 Minehead 1545 Jun 8-15: Ilfracombe Victorian Week Porthcawl 2000 Welsh Mountains Cruise Porlock Bay Clevedon 0830 SATURDAY June 15 Welcome Aboard by Steam Train Penarth 0930 Discover the Coasts, Rivers & Islands of the Bristol Minehead 1645/1700 Newport 1000 Ilfracombe 1345/1445 Penarth 1845 Ilfracombe 1215 Penarth 1130 Channel on a magical Day, Afternoon or Evening Cruise. Clevedon 2000 Lundy Island 1400/1630 Ilfracombe 1415/1430 Penarth 1745 Ilfracombe 1830 Cruise Exmoor Coast Clevedon -

Seascape Character Assessment Report

Seascape Character Assessment for the South West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the South West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2016 Marshall Maria Grant 1.0 Sally Updated draft final report following stakeholder Marshall/ consultation, August 2018 Kate Ahern 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Kate Ahern Final Report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

The Name of the Island of Annet, Isles of Scilly, Cornwall

73 RICHARD COATES UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST OF ENGLAND THE NAME OF THE ISLAND OF ANNET, ISLES OF SCILLY, CORNWALL The three earliest attestations of the Scillonian island-name Annet (UK Ordnance Survey NGR SV 860088) are in Assize Rolls of 1302, 1306 and 1336 (Padel 1988: 50). The spellings are respectively Anec (with commonplace confusion of <c> and <t> in medieval hands), Anete and Anet. The name has proved intractable. Thomas (1985: 43) explains it as deriving from Cornish anneth ‘dwelling’,1 but that should result in a modern name of the same pronunciation. I suggest instead that it derives from Old Irish andóit, a solution which has the merit of consistency with a minor emerging pattern in the toponymy of England, as I shall explain below. Following an original suggestion by Stokes (1893: 43; see also MacBain 1911, s.v. annaid, annoid), the word andóit is generally reckoned to be a borrowing from the postclassical Latin anttte(m)2 < antquitte(m) in the sense ‘ancient foundation’, and to have been mediated by Brittonic (see DIL s.v. andóit, following Vendryes).3 That being so, we should consider first whether our Cornish place- name could simply be a Brittonic survival. The form of the borrowed word would have changed by the expected battery of sound-changes up to about 600 CE as follows:4 1 See Padel (1985: 8) on this rare element, probably compounded with *bod, itself meaning ‘dwelling’, in both names in which it occurs. 2 This reduced form is found in Du Cange. 3 On the vowel stressed in British Latin, see also Jackson (1953: especially 124, 132), McManus (1983: 61-65), Etchingham (1993: 154).