1 Media Statement by Dr. Lim Chee Han, Senior Researcher at Penang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Producingtopeyehealthexperts

THE STAR, THURSDAY 6 MAY 2021 EDUCATION GUIDE Producing top eye health experts THE study of optometry opens the optometry has gone well beyond door to a healthcare profession spectacles and contact lenses. where the practitioner becomes “This philosophy is well embed- the first professional personnel to ded within SEGi’s Optometry prog- detect and diagnose visual disor- ramme, where students are trained ders and manages the functional in the examination of eye health in disorders of the visual system with generating prescriptions for cor- corrective optical prescriptions and recting their patients’ vision.” vision therapy. “Some graduates decide to re- To answer this need, SEGi examine or further their under- University (SEGi) offers one of the standing in some aspects of clinical most modern optometry degrees in vision science upon graduation. Malaysia, and is one of the few “With this understanding, many institutions to offer the optometry students are deciding to further programme at both the bachelor their studies by undertaking and masters degree levels. SEGi’s Masters of Science in Vision The Bachelor of Optometry Science by Research upon comple- (Hons) programme provides tion of their first degree in optome- knowledge and expertise in sub- try.” jects related to the identification The Master of Science (Vision and treatment of dysfunctions and Science) by Research programme disorders of vision, as well as the at SEGi aims to provide students vision system. with firm grounding in scholarly To ensure the highest quality of research work in clinical vision sci- education, SEGi’s Bachelor of ence, which encompasses a range Optometry (Hons) programme is of areas in clinical optometry. -

14Th Surgical Nursing & Nurse Education Conference

P Thamilselvam, Surgery Curr Res 2016, 6:5(Suppl) conferenceseries.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2161-1076.C1.022 14th Surgical Nursing & Nurse Education ConferenceOctober 10-11, 2016 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia P Thamilselvam Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia, Malaysia Complications of laparoscopic surgery aparoscopic cholecystectomy and appendicectomy remains one of the most common laparoscopic surgeries being Lperformed throughout the world in the present era. The advantages of laparoscopic surgery over open surgery have already been proven. Since the first documented laparoscopic cholecystectomy by Proffesor Muhe in 1985, over the years, it has become the gold standard for cholecystectomy. The advantages of laparoscopic surgery have been questioned recently due to reports of some complications inherent to the approach. These complications may be due to: Induction of pneumoperitoneum; insertion of trocars; use of thermal instruments and; lack of experience and expertise. Complications like bowel perforation and vascular injury may not be recognized intraoperatively and are the main cause of procedure specific morbidity and mortality related to laparoscopic surgery. Biography P Thamilselvam is working in National Defence University of Malaysia (UPNM). He specialized in General Surgery in 1987 (Madras Medical college –University of Madras ) and subsequently worked as Lap and General Surgeon in Chennai Apollo Hospitals, Maldives and various Universities in Malaysia-AIMST University International Medical University and Perdana University -

AIMST Newsletter

AIMST Newsletter (AIMST) Asian Institute of Medicine, Science and Technology This Newsletter is Intended for AIMST University’s Community and its Stakeholders VolumeVolume 1,2, Issue Issue 4 2 July-SeptemberNovember 2018 2019 Collaboration with the Royal College of Physi- cians of Ireland On the 1st July 2019, the President of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI), Prof. Dr Mary Horgan (3rd from left in the snap) visited AIMST Uni- versity accompanied by its regional repre- sentative, late Prof Datuk Seri Dr Jeyain- dran, and a physician from Hospital Sultan Abdul Halim Sg. Petani, Dr Tharmalin- gam. They were welcomed by Vice-Chancellor and Chief Executive of AIMST University, Emeritus Prof. Dr Harcharan Sing Sidhu (3rd from right in pic); and Dean Faculty of Medicine, Prof. Dr K.R. Sethuraman. The delegation had an exploratory discussion on various potential areas of collaborations in the health sciences. Collaboration with Indonesian Vocational (Nursing) Schools Association On the 11th July 2019, a delega- tion of 23 guests from various nursing colleges of Indonesia led by Prof. Teuku Shahrul Reza vis- ited AIMST Uni- versity to explore the possibility of collaboration. Emeritus Prof. Dr Harcharan Sing Sidhu, Vice-Chancellor and Chief Executive, together with the senior management team of AIMST University, welcomed them. Dr Yu Chye Wah briefed them on the nursing programmes and showed the facilities and laboratories. The Inbound AIMST Mobility Programme for their students and outbound elective posting for AIMST students will be initiated in due time. Published by: AIMST Sdn. Bhd (496741-P), Semeling, 08100 Bedong, Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia. -

SEASN Strategic Planning 2019-2021

SOUTH EAST ASIA SUSTAINABILITY NETWORK STRATEGIC PLANNING 2019-2021 i © South East Asia Sustainability Network (SEASN), Centre for Global Sustainability Studies (CGSS) 2019 All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from South East Asia Sustainability Network (SEASN), Centre for Global Sustainability Studies (CGSS), Universiti Sains Malaysia. Published by South East Asia Sustainability Network (SEASN) Centre for Global Sustainability Studies (CGSS) Level 5, Hamzah Sendut Library Universiti Sains Malaysia 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia Penang, Malaysia. Website: http://cgss.usm.my Email: [email protected] Editors Dr. Ng Theam Foo Dr. Suzyrman Sibly Dr. Mohd Sayuti Hassan Dr. Noor Adelyna Mohammed Akib Dr. Radieah Mohd Nor Dr. Normaliza Abdul Manaf Dr. Hamoon Khelghat-Doost Mohd Abdul Muin Md Akil Siti Izaidah Azmi Marlinah Muslim Sharifah Nurlaili Farhana Syed Azhar Shalini Velaithum Contributors Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Malaysia Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Malaysia Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia (USIM), Malaysia World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Malaysia Chulalongkorn University (CU), Thailand Corporate Responsibility & Ethics Association for Thai Enterprise (CREATE), Thailand Far Eastern University (FEU), Philippines Regional Centre of Expertise (RCE), Southern Vietnam Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka (UteM), Malaysia Regional Centre of Expertise (RCE), Penang, Malaysia Penang Water Watch, Malaysia Language Works Sdn. Bhd., Malaysia Aker Solution Asia Pacific Sdn. Bhd., Malaysia Penang Women’s Development Corporation (PWDC), Malaysia Design and Layout Siti Fairuz Mohd Radzi ii TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Global and Regional Challenges of Sustainability 1 2. -

AIMST Newsletter

e re F AIMST Newsletter THE NEWSLETTER OF THE ASIAN INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY THIS NEWSLETTER IS INTENDED FOR AIMST UNIVERSITY’S COMMUNITY AND STAKEHOLDERS Volume 2, Issue 3 October-December 2019 Educating Tomorrow's Leaders TUN SAMY VELLU: ARCHITECT OF AIMST UNIVERSITY Page 3 1 Page 2 AIMST Newsletter Contents Editorial Board Editor’s Note ....................................................................................................................... 3 Editor-in-Chief: Subhash J Bhore Tun Samy Vellu: Architect of AIMST University ................................................................. 3 Sectional Editors Message from the MIED Chairman .................................................................................... 6 Pharmacy: Mohd. Baidi Bahari The Ministry of Health Malaysia and AIMST University Launched KOSPEN Plus Program .6 Medicine: Matiullah Khan AIMST Received Excellence Award in Education from Chief Minister of Penang on Sin Dentistry: Durga Prasad Mudrakola Chew Daily’s 90th Anniversary........................................................................................... 9 Applied Sciences: Lee Su Yin Japanese Students at AIMST University ............................................................................ 9 Business & Management: Sham Abdulrazak 21st Century Trends in Medical Education and Sciences–2019 ........................................ 10 Engineering&Computer: Ravandran Muttiah Crowning of a Worthy Career for Dental Technology Graduates ...................................... -

Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Frgs) (Amendment Year 2021)

DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION GUIDELINES OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH GRANT SCHEME (FRGS) (AMENDMENT YEAR 2021) BAHAGIAN KECEMERLANGAN PENYELIDIKAN IPT JABATAN PENDIDIKAN TINGGI KEMENTERIAN PENGAJIAN TINGGI ARAS 7, NO. 2, MENARA 2 JALAN P5/6, PRESINT 5 62200 PUTRAJAYA TEL. NO.: 03-8870 6974/6975 FAX NO.: 03-8870 6867 TABLE OF CONTENTS Vision and Mission of Fundamental Research 3 PART 1 (INTRODUCTION) 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Philosophy 4 1.3 Definition 4 1.4 Purpose 4 PART 2 (APPLICATION) 2.1 General terms of application 5 2.2 Research priority areas 6 2.3 Research duration 8 2.4 Ceiling of fund 8 2.5 Research output 9 2.6 Application rules 10 PART 3 (ASSESSMENT) 3.1 Application assessment 11 3.2 Assessment criteria 12 PART 4 (MONITORING) 4.1 Research implementation 13 4.2 Monitoring 13 PART 5 (FINANCIAL REGULATIONS) 5.1 Expenditure codes 15 5.2 Use of provisions 16 PART 6 (RESULTS) 6.1 Result announcement and fund distribution 18 6.2 Agreement document and contract 18 APPENDICES 19 Application Flow Chart Monitoring Flow Chart Scheduled Monitoring Cycle List of Higher Education Institutions (Appendix A) 2 VISION AND MISSION OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH Vision Competitive fundamental research for knowledge transformation and national excellence. Mission Cultivate, empower and preserve high impact research capacity to generate knowledge that can contribute to talent development, intellectual growth, new technology invention and dynamic civilization. 3 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Amendment Year 2021 document is prepared as a reference and guide for application of research grant under the Department of Higher Education (JPT), Ministry of Higher Education (KPT). -

MERGED LIST from Scival and Incites Names Arranged

T1ABLE 24.3 - MERGED LIST FROM SCiVAL and InCites Names arranged alphabetically by MQA Registry SV=SciVal; IC is InCItes PUBLICATION RANKINGS SETARA TYPE 1 INSTITUTION SOURCE SV IC Tier Abbreviation Asia Metropolitan U was Master kill 2 College of Nursing & Health SV 67 Universiti Multimedia or University 2 Multimedia B 13 12 T 5 MMU AIMST-Asian Institute of Medicine, 2 Science & Technology B 39 36 T 4 Asia Pacific University of Technology and 2 Innovation SV 42 T 5 AP UTI Binary University of Management & 2 Entrepreneurship SV 63 BUCME 2 Curtin University , Sarawak MY IC 34 T 5 CMYS Cyberjaya University College of Medical 2UC Sciences SV 47 T 5 CSM GOV Forest Research Centre - Sandakan SV 46 FRC Forest Research Institute Malaysia (Inst GOV Penyelidikan Perhutanan) B 33 29 FRIM 2 Help University IC 41 T 4 2UC Heriot-Watt University Malaysia SV 60 HWUM GOV Hospital Pulau Pinang SV 44 Institute for Medical Research (Institut GOV Penyelidikan Perubatan) B NOTE 2 31 23 Institute Jantung Negara (Ntl Heart Inst. Corp with IJN College) IC 46 IJN Institute Penyelidikan Getah MY (part of GOV MY Rubber Board) IC 45 International Islamic University MY (Uni 1 Islam Antarabangsa ) B 7 9 T 5 IIUM 2 International Medical University B 21 22 T 5 IUM 2 INTI International University SV 41 T 5 INTIUI GOV Jabatan Hutan Sarawak (Forest Dep) IC 48 2UC KDU University College SV 66 KDUJP Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia GOV (Ministry of Health) B 34 33 2 C Kolej Teknologi Pulau(Island College) SV 64 MY 5 KCI 2UC Kolej Universiti Poly-Tech MARA SV 62 MY 4 KUPTM GOV -

How to Make the Most out of University

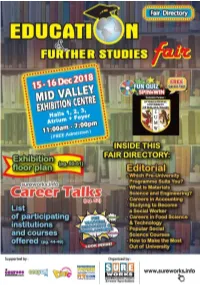

PROGRAMMES OFFERED PRE-U Pre-University Studies Pharmacy Foundation in Science Pharmacy Foundation in Business Dentistry Medicine and Biomedical Science Dental Technology Medical Laboratory Technology Dental Surgery (DDS) Biomedical Sciences IT IS TIME TO SET YOUR FUTURE Medicine & Surgery (MBBS) Nursing and Midwifery Nursing Health and Sport Sciences Midwifery WITH US Environmental Health Paediatric Nursing Medical Imaging Hospital Management Physiotherapy Health Care Practice Environmental Health and Safety Business, Finance and Engineering & Information S Hospitality S Technology Marketing Mechanical Engineering Restaurant Management Civil Engineering Hotel Management Electrical and Electronic Engineering Human Resource Management Accounting Business Administration PRE-U Islamic Finance WHAT’S AFTER SPM? 1-2 years ? Pre-U (A-Level, STPM, etc.) el v ? e L - Optional Scholarships O M / P for 2018 S 1 year 4 years Foundation Degree Employment Postgraduate Studies are You available Option 1: Option 2: now! Enter 2nd year of degree Straight to work 3 years Diploma 24 1800 88 0300 Follow us on: MAHSA University Bandar Saujana Putra Campus /MAHSAUniversity +603 5102 2200 Jalan SP 2, Bandar Saujana Putra, www.mahsa.edu.my /mahsauniversity [email protected] 42610 Jenjarom Selangor /MAHSAedu 4 Inside this fair directory Visit www.Sureworks.info for more information on courses and careers. 5 CONTENTS ADVERTISERS in this directory Message from 5 Welcome Message Datin Jercy Choo Which Pre-University Programme 6-7 Suits You? ACCA (The Association -

Social Media Monitoring Dashboard for University by Dicken Tan

SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 UNIVERSITI TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN REPORT STATUS DECLARATION FORM Title: SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY Academic Session: JAN 2020 I DICKEN TAN (CAPITAL LETTER) declare that I allow this Final Year Project Report to be kept in Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman Library subject to the regulations as follows: 1. The dissertation is a property of the Library. 2. The Library is allowed to make copies of this dissertation for academic purposes. Verified by, _________________________ _________________________ (Author’s signature) (Supervisor’s signature) Address: 146, JALAN PASIR PUTEH 31650 IPOH DR. PRADEEP ISAWASAN PERAK (Supervisor’s name) Date: 24 APRIL 2020 Date: 24 APRIL 2020 TITLE PAGE SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this report entitled “SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY” is my own work except as cited in the references. The report has not been accepted for any degree and is not being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signature : _________________________ Name : DICKEN TAN Date : 24 APRIL 2020 BCS (Hons) Computer Science Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus), UTAR. -

Curriculum Vitae

MM/SDNB/FEB2021 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME : DR. MARAN MARIMUTHU DESIGNATION : ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT : MANAGEMENT AND HUMANITIES E-MAIL ADDRESS : [email protected] UTP URL : https://www.utp.edu.my/directories/Pages/academic.aspx?persondetail=3221 CONTACT NO : 605-368-7770/016-3151025 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES Maran Marimuthu is an Associate Professor at the Department of Management and Humanities, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS. Maran Marimuthu holds a doctorate in Finance from University of Malaya in 2011. His Phd work is on capital structure involving GLCs and Non-GLCs in Malaysia. He obtained his MBA in Finance from University of Malaya in 2000 and his BBA (Hons) from Universiti Utara Malaysia in 1994. He teaches Financial Management, Engineering Economics, Corporate Finance and Research Methods in Business & Finance. To date, he has graduated 9 Masters and three PhD Scholars by research and 7 PhD. Dr. Maran has published more than 100 international refereed journals (including Q1, Q2 -ISI/SCOPUS journals) and conference proceedings (local and overseas). He has co-authored books on Financial Management, International Finance and contributed articles for both local and international magazines. He has served as a Trainer/Consultant in O&G industry including PETRONAS especially on socio- economic and cost analysis. In relation to academic contribution, he has been actively involved in the development of new degree programmes, including Finance Degree Programmes for Higher Learning Institutions. Dr. Maran Marimuthu is currently holding internal and external research grants as Principal and Co-Researcher and supervising doctoral and masters students in the related area. He also has a special interest in the multidisciplinary work. -

Our Partner Institutions List Study Abroad, Study Locally Or Both : the Choice Is Yours

SELSET Education Centre : Our Partner Institutions List Study Abroad, Study Locally or Both : The Choice is Yours NEW ZEALAND________________________________________________________________ Universities: - University of Auckland - AUT University - University of Waikato - Massey University - Victoria University of Wellington - University of Canterbury - Lincoln University - University of Otago Institute of Technology: - Toi Ohomai - ARA Institute of Canterbury - Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) - Manukau Institute of Technology (MIT) - Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (NMIT) - Open Polytechnic of New Zealand - Otago Polytechnic - Southern Institute of Technology (SIT) - Universal College of Learning (UCOL) - Unitec Institute of Technology - Waikato Institute of Technology (WINTEC) - Wellington Institute of Technology (WELTEC) - Whitireia New Zealand Private Institutions: - Aspire2 Group - New Zealand Tertiary College (NZTC) - Whitecliffe College of Arts & Design - Media Design School, Auckland - New Zealand School of Education - Pacific International Hotel Management School (PIHMS) - IPC Tertiary Institute - International Travel College (ITC) - Queenstown Resort College (QRC) - New Zealand School of Education (NZSE) - AGI Education - Royal Business College - Eagle Flight Training School - Air New Zealand Aviation Institute - Wellpark School of Natural Therapies Colleges and Schools: - ACG College Groups – For Foundation Studies, Secondary and Primary schools, Vocational Programs including New Zealand Careers College, NZMA, -

Garis Panduan Permohonan Application Guideline

APPLICATION GUIDELINE/REQUIREMENT GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN TERTIARY EDUCATION SPONSORSHIP PROGRAMME (TESP 2020) Open to all full-time student who are currently pursuing First Degree Programme at selected field and selected Local Higher Learning Institution. APPLICATIONS REQUIREMENTS • Application must be made online thru MARA Portal via: www.mara.gov.my starting 13th April 2020 (Monday) 10.00am until 4th May 2020 (Monday) 12.00pm. • Applicant must meet the general requirements and academic requirements. • If false information given by the applicant, MARA reserves the right to terminate or withdraw the loan offer. GENERAL REQUIREMENTS • Malaysian. • Applicant and either one parents is Bumipuera. • Meet the family Sosio Economy Status (SES) eligibility requirements set by MARA. • Parents total taxable income is not more than RM180,000 a year. If parents are self- employed or work at oversea, their average gross income must be less than RM 15,000 per month • Parents/Guardians and applicant are not blacklisted by MARA. • Applicant do not receive any financial support/sponsorship from any agency for current study programme (double sponsor). • Sponsorship is not given to applicant taking same programme level. • Free from any chronic/ contagious disease/ disease that require follow-up treatment. • Applicant age limit should not exceed 40 years old at the time of application. ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS New Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in Asasi/ Matriculation/ Persediaan/ STPM and equivalent. Existing Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in previous semester; AND • Their balance study is not less than a year. Others • Pass SPM with credit Bahasa Melayu. • Academic requirement for medicine, dentistry and pharmacy programme must be meet the criteria set by professional board.