Sin2014.Pdf (1.587Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14Th Surgical Nursing & Nurse Education Conference

P Thamilselvam, Surgery Curr Res 2016, 6:5(Suppl) conferenceseries.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2161-1076.C1.022 14th Surgical Nursing & Nurse Education ConferenceOctober 10-11, 2016 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia P Thamilselvam Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia, Malaysia Complications of laparoscopic surgery aparoscopic cholecystectomy and appendicectomy remains one of the most common laparoscopic surgeries being Lperformed throughout the world in the present era. The advantages of laparoscopic surgery over open surgery have already been proven. Since the first documented laparoscopic cholecystectomy by Proffesor Muhe in 1985, over the years, it has become the gold standard for cholecystectomy. The advantages of laparoscopic surgery have been questioned recently due to reports of some complications inherent to the approach. These complications may be due to: Induction of pneumoperitoneum; insertion of trocars; use of thermal instruments and; lack of experience and expertise. Complications like bowel perforation and vascular injury may not be recognized intraoperatively and are the main cause of procedure specific morbidity and mortality related to laparoscopic surgery. Biography P Thamilselvam is working in National Defence University of Malaysia (UPNM). He specialized in General Surgery in 1987 (Madras Medical college –University of Madras ) and subsequently worked as Lap and General Surgeon in Chennai Apollo Hospitals, Maldives and various Universities in Malaysia-AIMST University International Medical University and Perdana University -

Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Frgs) (Amendment Year 2021)

DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION GUIDELINES OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH GRANT SCHEME (FRGS) (AMENDMENT YEAR 2021) BAHAGIAN KECEMERLANGAN PENYELIDIKAN IPT JABATAN PENDIDIKAN TINGGI KEMENTERIAN PENGAJIAN TINGGI ARAS 7, NO. 2, MENARA 2 JALAN P5/6, PRESINT 5 62200 PUTRAJAYA TEL. NO.: 03-8870 6974/6975 FAX NO.: 03-8870 6867 TABLE OF CONTENTS Vision and Mission of Fundamental Research 3 PART 1 (INTRODUCTION) 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Philosophy 4 1.3 Definition 4 1.4 Purpose 4 PART 2 (APPLICATION) 2.1 General terms of application 5 2.2 Research priority areas 6 2.3 Research duration 8 2.4 Ceiling of fund 8 2.5 Research output 9 2.6 Application rules 10 PART 3 (ASSESSMENT) 3.1 Application assessment 11 3.2 Assessment criteria 12 PART 4 (MONITORING) 4.1 Research implementation 13 4.2 Monitoring 13 PART 5 (FINANCIAL REGULATIONS) 5.1 Expenditure codes 15 5.2 Use of provisions 16 PART 6 (RESULTS) 6.1 Result announcement and fund distribution 18 6.2 Agreement document and contract 18 APPENDICES 19 Application Flow Chart Monitoring Flow Chart Scheduled Monitoring Cycle List of Higher Education Institutions (Appendix A) 2 VISION AND MISSION OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH Vision Competitive fundamental research for knowledge transformation and national excellence. Mission Cultivate, empower and preserve high impact research capacity to generate knowledge that can contribute to talent development, intellectual growth, new technology invention and dynamic civilization. 3 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Amendment Year 2021 document is prepared as a reference and guide for application of research grant under the Department of Higher Education (JPT), Ministry of Higher Education (KPT). -

MERGED LIST from Scival and Incites Names Arranged

T1ABLE 24.3 - MERGED LIST FROM SCiVAL and InCites Names arranged alphabetically by MQA Registry SV=SciVal; IC is InCItes PUBLICATION RANKINGS SETARA TYPE 1 INSTITUTION SOURCE SV IC Tier Abbreviation Asia Metropolitan U was Master kill 2 College of Nursing & Health SV 67 Universiti Multimedia or University 2 Multimedia B 13 12 T 5 MMU AIMST-Asian Institute of Medicine, 2 Science & Technology B 39 36 T 4 Asia Pacific University of Technology and 2 Innovation SV 42 T 5 AP UTI Binary University of Management & 2 Entrepreneurship SV 63 BUCME 2 Curtin University , Sarawak MY IC 34 T 5 CMYS Cyberjaya University College of Medical 2UC Sciences SV 47 T 5 CSM GOV Forest Research Centre - Sandakan SV 46 FRC Forest Research Institute Malaysia (Inst GOV Penyelidikan Perhutanan) B 33 29 FRIM 2 Help University IC 41 T 4 2UC Heriot-Watt University Malaysia SV 60 HWUM GOV Hospital Pulau Pinang SV 44 Institute for Medical Research (Institut GOV Penyelidikan Perubatan) B NOTE 2 31 23 Institute Jantung Negara (Ntl Heart Inst. Corp with IJN College) IC 46 IJN Institute Penyelidikan Getah MY (part of GOV MY Rubber Board) IC 45 International Islamic University MY (Uni 1 Islam Antarabangsa ) B 7 9 T 5 IIUM 2 International Medical University B 21 22 T 5 IUM 2 INTI International University SV 41 T 5 INTIUI GOV Jabatan Hutan Sarawak (Forest Dep) IC 48 2UC KDU University College SV 66 KDUJP Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia GOV (Ministry of Health) B 34 33 2 C Kolej Teknologi Pulau(Island College) SV 64 MY 5 KCI 2UC Kolej Universiti Poly-Tech MARA SV 62 MY 4 KUPTM GOV -

Social Media Monitoring Dashboard for University by Dicken Tan

SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 UNIVERSITI TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN REPORT STATUS DECLARATION FORM Title: SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY Academic Session: JAN 2020 I DICKEN TAN (CAPITAL LETTER) declare that I allow this Final Year Project Report to be kept in Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman Library subject to the regulations as follows: 1. The dissertation is a property of the Library. 2. The Library is allowed to make copies of this dissertation for academic purposes. Verified by, _________________________ _________________________ (Author’s signature) (Supervisor’s signature) Address: 146, JALAN PASIR PUTEH 31650 IPOH DR. PRADEEP ISAWASAN PERAK (Supervisor’s name) Date: 24 APRIL 2020 Date: 24 APRIL 2020 TITLE PAGE SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY BY DICKEN TAN A REPORT SUBMITTED TO Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE (HONS) Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus) JAN 2020 i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this report entitled “SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING DASHBOARD FOR UNIVERSITY” is my own work except as cited in the references. The report has not been accepted for any degree and is not being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signature : _________________________ Name : DICKEN TAN Date : 24 APRIL 2020 BCS (Hons) Computer Science Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (Kampar Campus), UTAR. -

Our Partner Institutions List Study Abroad, Study Locally Or Both : the Choice Is Yours

SELSET Education Centre : Our Partner Institutions List Study Abroad, Study Locally or Both : The Choice is Yours NEW ZEALAND________________________________________________________________ Universities: - University of Auckland - AUT University - University of Waikato - Massey University - Victoria University of Wellington - University of Canterbury - Lincoln University - University of Otago Institute of Technology: - Toi Ohomai - ARA Institute of Canterbury - Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) - Manukau Institute of Technology (MIT) - Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (NMIT) - Open Polytechnic of New Zealand - Otago Polytechnic - Southern Institute of Technology (SIT) - Universal College of Learning (UCOL) - Unitec Institute of Technology - Waikato Institute of Technology (WINTEC) - Wellington Institute of Technology (WELTEC) - Whitireia New Zealand Private Institutions: - Aspire2 Group - New Zealand Tertiary College (NZTC) - Whitecliffe College of Arts & Design - Media Design School, Auckland - New Zealand School of Education - Pacific International Hotel Management School (PIHMS) - IPC Tertiary Institute - International Travel College (ITC) - Queenstown Resort College (QRC) - New Zealand School of Education (NZSE) - AGI Education - Royal Business College - Eagle Flight Training School - Air New Zealand Aviation Institute - Wellpark School of Natural Therapies Colleges and Schools: - ACG College Groups – For Foundation Studies, Secondary and Primary schools, Vocational Programs including New Zealand Careers College, NZMA, -

Garis Panduan Permohonan Application Guideline

APPLICATION GUIDELINE/REQUIREMENT GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN TERTIARY EDUCATION SPONSORSHIP PROGRAMME (TESP 2020) Open to all full-time student who are currently pursuing First Degree Programme at selected field and selected Local Higher Learning Institution. APPLICATIONS REQUIREMENTS • Application must be made online thru MARA Portal via: www.mara.gov.my starting 13th April 2020 (Monday) 10.00am until 4th May 2020 (Monday) 12.00pm. • Applicant must meet the general requirements and academic requirements. • If false information given by the applicant, MARA reserves the right to terminate or withdraw the loan offer. GENERAL REQUIREMENTS • Malaysian. • Applicant and either one parents is Bumipuera. • Meet the family Sosio Economy Status (SES) eligibility requirements set by MARA. • Parents total taxable income is not more than RM180,000 a year. If parents are self- employed or work at oversea, their average gross income must be less than RM 15,000 per month • Parents/Guardians and applicant are not blacklisted by MARA. • Applicant do not receive any financial support/sponsorship from any agency for current study programme (double sponsor). • Sponsorship is not given to applicant taking same programme level. • Free from any chronic/ contagious disease/ disease that require follow-up treatment. • Applicant age limit should not exceed 40 years old at the time of application. ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS New Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in Asasi/ Matriculation/ Persediaan/ STPM and equivalent. Existing Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in previous semester; AND • Their balance study is not less than a year. Others • Pass SPM with credit Bahasa Melayu. • Academic requirement for medicine, dentistry and pharmacy programme must be meet the criteria set by professional board. -

Lead in Medicine

Appointment of: Perdana University – Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (PU-RCSI) Lead in Medicine RCSI is delighted to invite applications for the position of Lead in Medicine for the PU-RCSI Undergraduate Medical Programme. Based at our Perdana University campus in the lively, multi-cultural and invigorating city of Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, this role offers the successful candidate a working opportunity of a lifetime. Contents: Job Description: Pages 2 - 5 PU-RCSI Programme Overview: Page 6 About Perdana University: Pages 6 – 9 The Curriculum – Page 10 About RCSI: Page 11 About Malaysia and Kuala Lumpur – Pages 12 - 15 1 Job Description: Job Title: RCSI Lead – Medicine Location: Perdana University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Reporting to: Dean, Perdana University-RCSI School of Medicine, with responsibility for the discipline area of Medicine to the Head of the Department of Medicine in RCSI Dublin Term of office: Whole time/3 year appointment, with potential for renewal 1.1 Objective The PU-RCSI Lead in Medicine will lead and participate in the development, direction, teaching, facilitation and examining of the undergraduate Medical teaching programmes at Perdana University – RCSI School of Medicine (“PU- RCSI”) in the area of Medicine. 1.2 The Position The role holder will deliver the RCSI curriculum in the diverse, multi-cultural environment of Kuala Lumpur and will liaise with RCSI Dublin on curriculum delivery, examinations and research matters, ensuring academic quality and consistency across the RCSI campuses. RCSI delivers the same medical degree programme and academic degrees across its campuses in Ireland, Bahrain and Malaysia. The PU-RCSI Lead in Medicine is responsible for delivering this same course and assessments, and for contribution to the continual renewal of this common programme. -

1 Media Statement by Dr. Lim Chee Han, Senior Researcher at Penang

Media Statement by Dr. Lim Chee Han, Senior Researcher at Penang Institute in Kuala Lumpur on the 21st of July, 2017 Ways to keep afloat with the housemanship programme in Malaysia Medical graduates in Malaysia having to wait for a year, sometimes more, before they can be placed for their housemanship training has been putting a heavy burden on the Ministry of Health as well as these aspiring doctors. The long queue for housemanship positions is driven by a number of factors namely: (i) A significant increase in the number of medical graduates from local private colleges and universities and an increase in the number of medical graduates from overseas driven by an increase in the number of overseas medical institutions which are recognized by the Malaysian Medical Council (MMC) (ii) The inability of the public health system to expand to keep up with the increasing number of medical graduates (iii) The declining rates of graduation within the stipulated period experienced by those undergoing the housemanship training programs with an especially high rate of non- graduation coming from medical graduates from certain overseas institutions The number of medical house officers i.e. those who have taken up their housemanship positions from local public universities increased from 496 in 2001 to 1245 in 2014, an increase of approximately 2.5 times. For local private institutions, the number of medical house officers increased from a mere 43 in 2001, when only the Penang Medical College was offering medical degrees, to 1125 in 2014, when 11 private institutions were offering medical degrees. This represents a 26-fold increase (See Appendix 1 below). -

Utpannualreport2014

Annual Report for the period 1 January to 31 December 2014. CONCEPT RATIONALE UTP’s Annual Report 2014 is a reflection of the future direction of the university. It is simple, yet bold and captivating, making a statement in itself. As Malaysia progresses towards the year 2020, UTP is marching forward as a contemporary institution, embracing the changes that come along our way to ensure that what we offer remains relevant to industry and society. The gold letters of our name against the pristine white background is reflective of our prominence in the education arena. We are bold, we are strong, we are contemporary and we hold firmly to strong corporate and social values. CONTENTS Corporate Profile • University Profile 4 • Vision and Mission 6 • Logo Rationale 7 The University Team • Chancellor 10 • Pro Chancellor 12 • Vice Chancellor 16 • Board of Directors 18 • Management Committee 20 • Senate 22 • Academic Advisory Council 24 • Research Advisory Council 25 • Student Development Advisory Council 26 • International External Examiners 27 • Industry Advisory Panel 28 The Reports • Chairman’s Review 32 • Vice Chancellor’s Report 38 • Academic 62 • Research and Innovation 76 • Student Affairs and Alumni 92 • Corporate Social Responsibility 104 Annual Report 2014 | 2 Corporate PROFILE • University Profile • Vision and Mission • Logo Rationale Annual Report 2014 | 3 Annual Report 2014 | 4 UNIVERSITY PROFILE Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP) is built UTP presently sees industry participation from more on a 400-hectare (1,000 acre) site strategically than 400 companies offering internship placements located 30 km southwest of Ipoh City at Seri for its students, including overseas companies. -

Exhibitors Booth No

Exhibitors Booth No. AIMST UNIVERSITY T29 - T30 ASA OVERSEAS A1 - A8 EDUCATION SPECIALIST ASIA METROPOLITAN T9 - T12 UNIVERSITY ASIA PACIFIC T1 - T4 UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION (APU) ATIC INTERNATIONAL H29 - H34 COLLEGE BERJAYA UNIVERSITY E15 - E20 COLLEGE OF HOSPITALITY BRITISH COUNCIL T34 BUTTER & OLIVE BAKING S6 ACADEMY KLMU & COSMOPOINT S1 CURTIN UNIVERSITY T21 - T22 DASEIN ACADEMY OF ART U29 DESPARK COLLEGE V1 - V2 DISTED COLLEGE H19 - H24 EDUCATION IRELAND F13 - F14 EDUCATION USA - MACEE S10 EQUATOR ACADEMY OF H7 - H12 ART FAIRVIEW S5 INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL PENANG GERMAN-MALAYSIAN U30 INSTITUTE GOON INSTITUTION SDN R6 - R8 BHD HAN CHIANG COLLEGE B9 - B14 HELP UNIVERSITY T17 - T20 HERIOT-WATT U31 UNIVERSITY HOLIDAY TOURS & U28 TRAVEL INFRASTRUCTURE U34 UNIVERSITY KL (IUKL) INNOVATIVE S3 ENGINEERING DESIGN COLLEGE INTER EXCEL TOURISM F15 - F20 ACADEMY INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE V3 - V4 OF AUTOMOTIVE (ICAM) INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL A9 - A14 UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL U35 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA WALES STUDY IN UK, IRELAND, U33 USA, AUS, NZ & S’PORE INTI INTERNATIONAL C1 - C12 UNIVERSITY & COLLEGES JMECC - AUS, NZ, UK, US, U26 CANADA & SG KBU INTERNATIONAL S12 COLLEGE KDU COLLEGE D1 - D16 KEMAYAN ATC E11 - E14 KLC PLACEMENT L1 - L2 PATHWAY TO SUCCESS LASALLE COLLEGE OF THE R1 ARTS LIMKOKWING UNIVERSITY OF CREATIVE E1 - E10 TECHNOLOGY MAHSA UNIVERSITY H1 - H6 MALAYSIAN INSTITUTE U36 OF ART (MIA) MANAGEMENT & SCIENCE A15 - A20 UNIVERSITY (MSU) MANIPAL U21 - U23 INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MEDIC ED CONSULTANTS B15 - B18 SDN BHD MEDIC PRO LINK SDN -

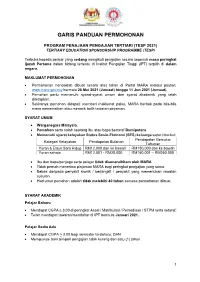

Garis Panduan Permohonan

GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN PROGRAM PENAJAAN PENGAJIAN TERTIARI (TESP 2021) TERTIARY EDUCATION SPONSORSHIP PROGRAMME (TESP) Terbuka kepada pelajar yang sedang mengikuti pengajian secara sepenuh masa peringkat Ijazah Pertama dalam bidang tertentu di Institut Pengajian Tinggi (IPT) terpilih di dalam negara. MAKLUMAT PERMOHONAN • Permohonan hendaklah dibuat secara atas talian di Portal MARA melalui pautan: www.mara.gov.my bermula 28 Mei 2021 (Jumaat) hingga 11 Jun 2021 (Jumaat). • Pemohon perlu memenuhi syarat-syarat umum dan syarat akademik yang telah ditetapkan. • Sekiranya pemohon didapati memberi maklumat palsu, MARA berhak pada bila-bila masa menamatkan atau menarik balik tawaran pinjaman. SYARAT UMUM • Warganegara Malaysia. • Pemohon serta salah seorang ibu atau bapa bertaraf Bumiputera • Memenuhi syarat kelayakan Status Sosio-Ekonomi (SES) keluarga seperti berikut: Pendapatan Bercukai Kategori Kelayakan Pendapatan Bulanan Tahunan Yuran & Elaun Sara Hidup RM12,000 dan ke bawah RM150,000 dan ke bawah Yuran sahaja RM12,001 - RM20,000 RM150,001 – RM250,000 • Ibu dan bapa/penjaga serta pelajar tidak disenaraihitam oleh MARA. • Tidak pernah menerima pinjaman MARA bagi peringkat pengajian yang sama. • Bebas daripada penyakit kronik / berjangkit / penyakit yang memerlukan rawatan susulan. • Had umur pemohon adalah tidak melebihi 40 tahun semasa permohonan dibuat. SYARAT AKADEMIK Pelajar Baharu • Mendapat CGPA > 3.00 di peringkat Asasi / Matrikulasi / Persediaan / STPM serta setaraf; • Telah mendapat tawaran/mendaftar di IPT bermula Januari 2021. Pelajar Sedia Ada • Mendapat CGPA > 3.00 bagi semester terdahulu; DAN • Mempunyai baki tempoh pengajian tidak kurang dari satu (1) tahun. 1 Lain-Lain Syarat • Lulus dengan kepujian dalam subjek Bahasa Melayu di peringkat SPM. • Kelayakan akademik bagi program Perubatan, Pergigian dan Farmasi mestilah memenuhi kriteria yang ditetapkan oleh Badan-Badan Profesional. -

Senarai Institusi Pengajian Tinggi Swasta

Lampiran B SENARAI INSTITUSI PENGAJIAN TINGGI SWASTA NO UNIVERSITI 1 ALLIANZE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES (A 2 AL-MADINAH INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY (MEDIU) 3 ASIA E UNIVERSITY (AEU) 4 ASIA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY 5 ASIA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION 6 BINARY UNIVERSITY OF MANAGEMENT & ENTREPRENEURSHIP 7 CITY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY (C 8 CURTIN UNIVERSITY, SARAWAK 9 DRB-HICOM UNIVERSITY OF AUTOMOTIVE MALAYSIA 10 FIRST CITY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE 11 GLOBALNXT UNIVERSITY 12 HERIOT-WATT UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA (HWUM) 13 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL UNIVERSITY (IMU) 14 INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIEN 15 INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA WALES (IUMW) 16 KDU UNIVERSITY COLLEGE 17 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI AGROSAINS MALAYSIA 18 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI BESTARI 19 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI BORNEO UTARA (KUBU) 20 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI GEOMATIKA 21 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI HOSPITALITI BERJAYA 22 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM ANTARABANGSA SELANGOR (KUIS 23 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM INSANIAH (KUIN) 24 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM MELAKA (KUIM) 25 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM PAHANG SULTAN AHMAD SHAH (K 26 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM PERLIS 27 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM SAINS DAN TEKNOLOGI (KUIST) 28 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM SULTAN AZLAN SHAH (KUISAS) 29 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI KDU PENANG 30 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI KPJ HEALTHCARE (KPJ HEALTHCARE UN 31 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI LINCOLN 32 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI LINTON (LINTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE 33 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI POLY-TECH MARA KUALA LUMPUR (KUPT 34 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI SAINS KESIHATAN MASTERSKILLS 35 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI SAINS PERUBATAN CYBERJAYA 36 KOLEJ