Report on the Inquiry Into Aspects of Petitioning Security and Accessibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Can Download the NSW Caring Fairly Toolkit Here!

A TOOLKIT: How carers in NSW can advocate for change www.caringfairly.org.au Caring Fairly is represented in NSW by: www.facebook.com/caringfairlycampaign @caringfairly @caringfairly WHO WE ARE Caring Fairly is a national campaign led by unpaid carers and specialist organisations that support and advocate for their rights. Launched in August 2018 and coordinated by Mind Australia, Caring Fairly is led by a coalition of over 25 carer support organisations, NGOs, peak bodies, and carers themselves. In NSW, Caring Fairly is represented by Mental Health Carers NSW, Carers NSW and Flourish Australia. We need your support, and invite you to join the Caring Fairly coalition. Caring Fairly wants: • A fairer deal for Australia’s unpaid carers • Better economic outcomes for people who devote their time to supporting and caring for their loved ones • Government policies that help unpaid carers balance paid work and care, wherever possible • Politicians to understand what’s at stake for unpaid carers going into the 2019 federal election To achieve this, we need your help. WHY WE ARE TAKING ACTION Unpaid carers are often hidden from view in Australian politics. There are almost 2.7 million unpaid carers nationally. Over 850,000 people in Australia are the primary carer to a loved one with disability. Many carers, understandly, don’t identify as a ‘carer’. Caring Fairly wants visibility for Australia’s unpaid carers. We are helping to build a new social movement in Australia to achieve this. Unpaid carers prop up Australian society. Like all Australians, unpaid carers have a right to a fair and decent quality of life. -

Election Inquiry to Hold Hearings in Brisbane and Tweed Heads

MEDIA RELEASE 5 July 2005 JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL MATTERS Chair: Tony Smith MP Deputy Chair: Michael Danby MP Inquiry into the conduct of the 2004 federal election Inquiry to probe conduct of federal election campaign An inquiry into the conduct of the 2004 federal election continues this week with public hearings in Brisbane and Tweed Heads on 6 and 7 July. Federal parliament’s Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters has a brief to examine the conduct of the 2004 federal election and any other matters related to Australia’s electoral law. Already the committee, which comprises members of the Government, Opposition and the Australian Democrats, has held hearings in regional Queensland to gather evidence of the major problems with postal voting that occurred in that area. The committee will continue its hearings program throughout July and August, starting in Brisbane (6 July) and Tweed Heads (7 July) before heading to Melbourne (25 July) and Adelaide (26 July), and Perth, Canberra and Sydney in August. In Brisbane, the committee will hear from several people who have made submissions to the inquiry, before heading to Tweed Heads, far north NSW, to examine the election campaign in the electorate of Richmond. Richmond was the fourth-closest election result in the country, with Labor’s Justine Elliot winning the seat from incumbent Larry Anthony (The Nationals) by 301 votes. The committee will explore some of the issues that submissions to its inquiry have raised about the election in Richmond, including party how-to-vote cards and the high rate of provisional voting. -

List of Senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 19.1 – 20 September 2021 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7860 Minister for Home Affairs QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7. -

Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of Personal Ideology in Politician's

Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of personal ideology in politician's speeches on Same Sex Marriage Preliminary and incomplete 2020-09-17 Current Version: http://eamonmcginn.com/papers/Same_Sex_Marriage.pdf. By Eamon McGinn∗ There is an emerging consensus in the empirical literature that politicians' personal ideology play an important role in determin- ing their voting behavior (called `partial convergence'). This is in contrast to Downs' theory of political behavior which suggests con- vergence on the position of the median voter. In this paper I extend recent empirical findings on partial convergence by applying a text- as-data approach to analyse politicians' speech behavior. I analyse the debate in parliament following a recent politically charged mo- ment in Australia | a national vote on same sex marriage (SSM). I use a LASSO model to estimate the degree of support or opposi- tion to SSM in parliamentary speeches. I then measure how speech changed following the SSM vote. I find that Opposers of SSM be- came stronger in their opposition once the results of the SSM na- tional survey were released, regardless of how their electorate voted. The average Opposer increased their opposition by 0.15-0.2 on a scale of 0-1. No consistent and statistically significant change is seen in the behavior of Supporters of SSM. This result indicates that personal ideology played a more significant role in determining changes in speech than did the position of the electorate. JEL: C55, D72, D78, J12, H11 Keywords: same sex marriage, marriage equality, voting, political behavior, polarization, text-as-data ∗ McGinn: Univeristy of Technology Sydney, UTS Business School PO Box 123, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia, [email protected]). -

Marginal Seat Analysis – 2019 Federal Election

Australian Landscape Architects Vote 2019 Marginal Seat Analysis – 2019 Federal Election Prepared by Daniel Bennett, Fellow, AILA The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) classifies seats based on the percentage margin won on a ‘two candidate preferred’ basis, which creates a calculation for the swing to change hands. Further, the AEC classify seats based on the following terms: • Marginal (less than 6% swing or 56% of the vote) • Fairly safe (between 6-10% swing or 56-60% of the vote) • Safe (more than 10% swing required and more than 60% of the vote) As an ardent follower of all elections, I offer the following analysis to assist AILA in preparing pre- election materials and perhaps where to focus efforts. As the current Government is a Coalition of the Liberal and National Party, my focus is on the fairly reliable (yet not completely correct) assumption that they have the most to lose and will find it hard to retain the treasury benches. Polls consistently show the Coalition on track to lose from 8 up to 24 seats, which is in plain terms a landslide to the ALP. However polls are just that and have been wrong so many times. So lets focus on what we know. The Marginals. According to the latest analysis by the AEC and the ABC’s Antony Green, the Coalition has 22 marginal seats, there are now 8 cross bench seats, of which 3 are marginal and the ALP have 24 marginal seats. This is a total of 49 marginal seats – a third of all seats! With a new parliament of 151 seats, a new government requires 76 seats to win a majority. -

Record of Proceedings

ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-assembly/hansard Email: [email protected] Phone (07) 3406 7314 Fax (07) 3210 0182 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT Tuesday, 5 May 2015 Subject Page SPEAKER’S STATEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 269 School Group Tour............................................................................................................................................ 269 Vacancy in Senate of Commonwealth of Australia ......................................................................................... 269 Tabled paper: Letter, dated 17 April 2015, from His Excellency the Governor to the Speaker advising of a vacancy in the Senate. ................................................................................................. 269 Tabled paper: Letter, dated 15 April 2015, from the President of the Senate, Mr Stephan Parry, to His Excellency the Governor advising of a vacancy in the Senate................................................. 269 PRIVILEGE ........................................................................................................................................................................... 269 Alleged Deliberate Misleading of the House by a Member ............................................................................. 269 REPORTS ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

List of Members 46Th Parliament Volume 6.4 – 03 June 2020

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 6.4 – 03 June 2020 No. Name Electorate, Party Electorate office details, E-mail address Parliament House State/Territory telephone, fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422, Fax: N/A 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517, Fax: (08) 9409 9361 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7070 Minister for Industry, Science and QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Technology Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. -

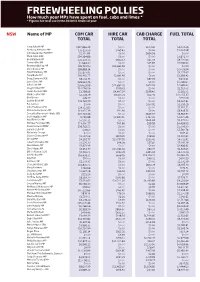

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00 -

• NGT-1012-8-13.Indd

Minister Howard government will result in a censoring undertaken. attacked the rights of public debate unlike anything I was one of the Labor members and legitimate role we have seen since the previous of Parliament who pushed this Janelle’s Page of the NFP sector Federal Coalition Government, issue in Caucus. From day one and diminished when Prime Minister Howard when I first heard of this rapacious by Janelle Saffin, MP A strong, its capacity to made gag clauses mandatory in all proposal I voiced my opposition independent and represent and funding contracts, which also led to to it, to concerned locals, senior I’m pleased to report that the innovative NFP advocate for its significant defunding of community ministers and the media. Federal Government is to legislate to sector is essential members. organisations. We were told that this floating ban gag-clauses in Commonwealth for the functioning In 2008 the We can only hope the O’Farrell fish factory, able to suck in mega contracts with the not-for-profits of our society and Federal Labor Coalition Government doesn’t catches, was sustainable but I (NFP) sector. good for our way of Government follow the Queensland Government was not convinced that a vessel I believe in free speech, even if at life. The people who removed the gag- down this track, but given what it of this size would operate in a times, it can be uncomfortable, and work in this sector as clauses imposed by is doing to education and health we sustainable way. And, who wants a our NFP sector must be able to employees and volunteers contribute the Coalition that had restricted the need to be on guard. -

Impact Analysis Legislative and Policy Achievements of EMILY's List

When Women Support Women, Emily’s LIST Women Win AUSTRALIA Impact analysis Legislative and policy achievements of EMILY’s List women in power Federal Parliament 2007-2013 Emily’s LIST AUSTRALIA When Women EMILY’s List Australia Phone (03) 8668 8120 Fax (03) 8668 8125 Support Women, [email protected] www.emilyslist.org.au Women Win 1/3/14 9:01:26 PM Contents Foreword 2 Introduction 3 EMILY’s List - a snapshot 4 Legislative reform 5 EMILY’s List in Federal Parliament 7 Case study: Julia Gillard 8 Legislative Achievements 9 Choice 9 Case study: Jenny Macklin 10 Child Care 11 Diversity 12 Equity 13 When Women Equal Pay 14 Case study: Tanya Plibersek 14 Support Women, Conclusion 16 Women Win Acknowledgments 16 Appendix 1: EMILY’s List supported women MPs 2007-2013 18 Appendix 2: EMILY’s List supported women in ministries, 2007-2013 19 Appendix 3: Legislation and policy initiatives 2007-2013 20 References 25 Background Note: This impact analysis was commissioned by the EMILY’s List National Committee and prepared by Sophie Arnold as part of a Bachelor of Legal Studies (Latrobe University) placement with EMILY’s List Australia. We gratefully acknowledge contributions from EL’s National Co-Convenors Tanja Kovac and Senator Anne McEwen, EL’s National Coordinator, Lisa Carey and Leonie Morgan, as well as all of our EMILY’s List MPs in the preparation of this report. Contents Foreword 2 Introduction 3 EMILY’s List - a snapshot 4 Legislative reform 5 EMILY’s List in Federal Parliament 7 Case study: Julia Gillard 8 Legislative Achievements -

4 December 2011

As at 24/11/11 46th National Conference 2 – 4 December 2011 Delegates and Proxies President and Vice Presidents To be advised Federal Parliamentary Leaders Delegates Proxy Delegates Julia Gillard Wayne Swan Chris Evans Stephen Conroy Federal Parliamentary Labor Party Representatives Delegates Doug Cameron David Feeney Gavin Marshall Anne McEwen Amanda Rishworth Matt Thistlethwaite Australian Young Labor Delegates Sarah Cole David Latham Mem Suleyman Australian Capital Territory Delegates & Proxies Katy Gallagher – Chief Minister Delegates Proxy Delegates Andrew Barr Meegan Fitzharris Dean Hall Amy Haddad Luke O'Connor Klaus Pinkas Alicia Payne Kristin van Barneveld Athol Williams Elias Hallaj, Non-voting Territory Secretary New South Wales Delegates and Proxies John Robertson - Leader of the Opposition Linda Burney – Leader’s Proxy Delegates Proxy Delegates Anthony Albanese Ed Husic Rob Allen Gerry Ambroisine Veronica Husted George Barcha Kirsten Andrews Rose Jackson Susai Benjamin Mark Arbib Johno Johnson Danielle Bevins-Sundvall Louise Arnfield Michael Kaine Alex Bukarica Timothy Ayres Graeme Kelly Meredith Burgmann Stephen Bali Grahame Kelly Michael Butterworth Paul Bastian Janice Kershaw Tony Catanzariti Derrick Belan Judith Knight Brendan Cavanagh Sharon Bird Michael Lee Jaime Clements Stephen Birney Mark Lennon Jeff Condron David Bliss Sue Lines Sarah Conway Phillip Boulten Rita Mallia Anthony D’Adam Christopher Bowen Maurice May Michael Daley Mark Boyd Jennifer McAllister Jo-Ann Davidson Corrine Boyle Robert McClelland Felix Eldridge -

List of Members 46Th Parliament Volume 12.3 – 23 December 2020

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 12.3 – 23 December 2020 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7070 Minister for Industry, Science and QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Technology Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7.