Indigenous Subjectivities, Inequalities and Kinship Under the Peruvian Family Planning Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primera Legislatura Ordinaria De 2014 17.ª Sesión

Estamos para servirlo de lunes a viernes de 09:00 a 17:00 horas Av. Abancay 251 - Piso 10 Teléfono 311-7777 anexos 5152 - 5153 - 5154 http://www.congreso.gob.pe E-mail: [email protected] PRIMERA LEGISLATURA ORDINARIA DE 2014 17.ª SESIÓN (Matinal) JUEVES 13 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2014 PRESIDENCIA DEL SEÑOR NORMAN DAVID LEWIS DEL ALCÁZAR Y DE LA SEÑORA ANA MARÍA SOLÓRZANO FLORES SUMARIO Se pasa lista.— Se abre la sesión.— Admitidas a debate, se inicia la discusión de las mociones de orden del día 11785 y 11890; la primera, mediante la cual se propone constituir una comisión investigadora, por un lapso de 180 días, encargada de investigar las denuncias periodísticas sobre las presuntas actividades ilícitas del prófugo Martín Belaunde Lossio; la segunda, por la cual se propone constituir una comisión especial investigadora multipartidaria encargada de investigar, por un plazo de 180 días, contados desde su instalación, la gestión de intereses particulares en la Administración Pública durante el período 2006-2014, tales como el presunto favorecimiento a las empresas Exalmar y Fénix Power y la participación del señor Martín Belaunde Lossio en el IPD para adjudicar contratos a la empresa española Antalsis; luego de un largo debate, los autores de las sendas mociones presentan un texto de consenso de ambas mociones, mediante el cual se propone constituir una comisión especial investigadora multipartidaria encargada de investigar por un plazo de 180 días contados desde su instalación, la gestión de intereses particulares en la Administración -

Artist and Entrepreneur

Artist and Entrepreneur Identifying and developing key qualifications pertaining cultural entrepreneurship for musical acts Eskil Immanuel Holm Jessen Master thesis at the Institute of Musicology UNIVERSITY OF OSLO May 2018 II Foreword I would like to thank my supervisor Per Ole Hagen for all his encouragement, inspiration and initiative, without which I would have been in a sorry state. I would like to thank my respondents for their participation, without which this thesis would never have seen the light of day. They have been eager to share of their knowledge of the music industries and their thoughts and perspectives regarding artists they work with, I will be forever grateful to them. A great deal of gratitude is sent in the direction of my good friend Milad Amouzegar, who has been a great team player through this entire endeavor, I thank you for all our long nights and early mornings of writing, proofreading and discussing our theses. To all my friends and family whom has been unrelenting in their belief and support these last two years, my deepest and most sincere thanks, you are all a part of this. Lastly, I would like to thank the institute of musicology for the opportunity to realize this thesis and especially Associate Professor Kyle Devine who made me realize just how exiting musicology can be at its best. Oslo, May 1st 2018 Eskil Immanuel Holm Jessen III IV Identifying and developing key qualifications pertaining cultural entrepreneurship for musical acts Eskil Immanuel H. Jessen Institute of Musicology V Copyright Eskil Immanuel H. Jessen 2018 Artist and Entrepreneur: Identifying and developing key qualifications pertaining cultural entrepreneurship for musical acts Eskil Immanuel H. -

To Israelite

From ‘Proud Monkey’ to Israelite Tracing Kendrick Lamar’s Black Consciousness Thesis by Romy Koreman Master of Arts Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Supervisor: Dr. Maria Boletsi Leiden University, April 2019 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Chapter 1: Theoretical framework ............................................................................................................. 9 W.E.B. Du Bois’ double-consciousness ............................................................................................... 9 Regular and critical double-consciousness ......................................................................................... 13 Chapter 2: To Pimp A Butterfly ................................................................................................................... 17 “Wesley’s Theory”.................................................................................................................................. 18 “Institutionalized” .................................................................................................................................. 20 “Alright” .................................................................................................................................................. 23 “Complexion” ........................................................................................................................................ -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1952-01-19

~ The Weather On The Inside ContiDlled mild w.,. wiUJ. _uloDaI .bowen. tram Other eou.q. Sancla,. coWer -.nil ..... Pav- I alble IDOW. Rlab 1Oday. Former UN l)eleqcne Speaks 50; low. 30. Rlfb Frlcta7 • . Pd9. S 41; low, n. Iowa Prepares for MlDDetIOta • at • • • paqe 4 Est. 1868 - AP Leased Wire, AP Wirephoto - Five Centa Outsiders Called NATO Naval Command, I • To Aid In CI,eanup WASHINGTON (JP) - Attorney To Go To An America'n' General McGrath said Friday Bills fo, letty as - nilht he will use "outside attor neys" as special assistants in a England To Get drive to sweep wrongdoers out of Balm Denied for Cows' .Sore Feel the federal government. • Tots Swell LITTLETON, COLO. (JP) - Damages for mental sufferi ng cannot In his flrst public comment on be claimed because your cows hove sore feet, District Judge Harold J . Davies l"Uled Thur'day. 1 Million Tons the ' task to wh ich Presidllnt Tru Gleen and Ado Pog chatged their neighbor, W. H. Lane, built a man has assigned him. McGrath Polio Fund "spite" rence along hiS ploperty, callsing them to drive their dairy said the outside attorneys will be herd over a longer route to pasture, resulting I n loss of mHk produc Of u.s: Steel selected on a basis or merit and tion, sore feei fOl' the cows ond mental ongulsh ror the owners. qualification "without any parti A one-dollar* *blll *doesn't last Judge Davies threw out the mental anguish charge on which they WASHINGTON (JP) - Prime san consideration." long any more when It comes to asked $15,000 damages. -

Comisiones Investigadoras Periodo Legislativo 2011 - 2016

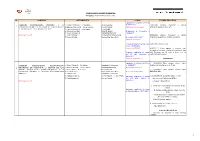

COMISIONES INVESTIGADORAS PERIODO LEGISLATIVO 2011 - 2016 N° COMISIÓN INTEGRANTES PLAZO ESTADO PROCESAL Aprobado en la Sesión del Pleno 1. Rogelio Canches G. - Presidente Unión Regional el 08/09/2011 27/04/2012 Informe Preliminar y solicita 1 COMISIÓN INVESTIGADORA REFERIDA A LA RECONSTRUCCIÓN DE LAS ZONAS AFECTADAS POR EL 2. Eduardo Cabrera G. - Vicepresidente Fuerza Popular Plazo 6 meses calendario ampliación de plazo de un año TERREMOTO DEL 15 DE AGOSTO DE 2007 3. Carmen Omonte D. - Secretaria Perú Posible 4. Humberto Lay Sun Unión Regional Designación de integrantes el 5. Vicente Zeballos S. Solidaridad Nacional 13/10/2011 Mociones 71 y 204 6. Elías Rodriguez Z. Concertación Parlamentaria 07/05/2013 Informe Preliminar y solicita 7. Manuel Zerrillo. Nacionalista Gana Perú Se instaló el 02/11/2011 ampliación de plazo de 30 días calendario. Vence el 02/05/2012 Primera ampliación de plazo por 06/06/2013 Informe Final 1 año el 03/05/2012 Vence el 02/05/2013 06/06/13 El Pleno aprobó el Informe Final, retirando el extremo referido al exministro José Segunda ampliación de plazo Luis Carranza, por 82 votos a favor, cero en por 30 días calendario el contra y 6 abstenciones. 09/05/2013 Vence el 17/06/2013 TERMINADO Aprobado en la Sesión del Pleno 1_ 19/06/2014 Pleno aprobó informe sobre COMISIÓN INVESTIGADORA MULTIPARTIDARIA 1. Sergio Tejada G. - Presidente Dignidad y Democracia el 14/09/2011 Indultos y Conmutaciones de Pena. 2 ENCARGADA DE INVESTIGAR LA GESTIÓN DE ALAN 2. Enrique Wong P. - Vicepresidente Solidaridad Nacional Plazo 365 días hábiles GABRIEL GARCÍA PÉREZ, COMO PRESIDENTE DE LA 3. -

Orienting Fandom: the Discursive Production of Sports and Speculative Media Fandom in the Internet Era

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository ORIENTING FANDOM: THE DISCURSIVE PRODUCTION OF SPORTS AND SPECULATIVE MEDIA FANDOM IN THE INTERNET ERA BY MEL STANFILL DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications with minors in Gender and Women’s Studies and Queer Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor CL Cole, Co-Chair Associate Professor Siobhan Somerville, Co-Chair Professor Cameron McCarthy Assistant Professor Anita Chan ABSTRACT This project inquires into the constitution and consequences of the changing relationship between media industry and audiences after the Internet. Because fans have traditionally been associated with an especially participatory relationship to the object of fandom, the shift to a norm of media interactivity would seem to position the fan as the new ideal consumer; thus, I examine the extent to which fans are actually rendered ideal and in what ways in order to assess emerging norms of media reception in the Internet era. Drawing on a large archive consisting of websites for sports and speculative media companies; interviews with industry workers who produce content for fans; and film, television, web series, and news representations from 1994-2009 in a form of qualitative big data research—drawing broadly on large bodies of data but with attention to depth and texture—I look critically at how two media industries, speculative media and sports, have understood and constructed a normative idea of audiencing. -

Medienmitteilung (Quelle: Open Air Gampel)

Programm-Release III Open Air Gampel 14.-17.08.2014 «The best party of my life» Mit den bisherigen Bestätigungen hat ‚Gampel‘ mit Volbeat, Marilyn Manson, Mandio Diao und anderen bereits einige heisse Perlen angekündigt. Das mittlerweile dritte Bandpaket steht nun für das, was ‚Gampel‘ gross macht: nämlich «Ischi Party»! Und um dem gerecht zu werden, musste der ultimative Partykracher her – überraschend und exklusiv! Einfach Scooter! Scooter mit «20 years of hardcore» verkauften weltweit über 30 Millionen Tonträger und waren während über 500 Wochen in den Charts vertreten. In Kürze erscheint mit «The fifth chapter» das brandneue Album. In dieselbe Kerbe schlagen Clean Bandit. Mit ihrem Nummer-Eins-Hit «Rather be» gehören sie in den Charts, Clubs und auch auf den Bühnen zu den grossen Newcomern dieses Jahres. Auch die Band American Authors hat eine grosse Chartpräsenz. Ihr Folk-Song «Best day of my life» steht rund um den Globus praktisch überall in den Top10. In Amerika wurde der Track bereits über 1 Million mal verkauft. Auch das diesjährige DJ-Line-up ist vollgespickt mit vielen Chartstürmern; unter ihnen Faul & Wad AD, Remady & Manu L, DJ ZsuZsu und Alex Price. Ergänzt wird dieses Bandpaket mit Bear Hands, einer Indie-Rock-Band mit grosse Zukunft, den Tessinern von Sinplus, den experimentierfreudigen Yokko, den Top-5-Rappern von Lo & Leduc, dem unverwüstlichen Plüsch-Urgetier Ritschi und vor allem mit den mysteriösen Kadebostany. Es ist dies wohl eine der derzeit spannendsten Bands schweizweit mit einem riesigen internationalen Potential. Freuen darf man sich auch auf die Verpflichtung der Kyle Gass Band, der einen Hälfte des sensationellen Duos Tenacious D. -

Scooter Am 28. August 2015 Open Air Auf Der Trabrennbahn Bahrenfeld

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 21.10.2014 Hyper Hyper – dritte Bestätigung für den Hamburger Kultursommer 2015: Scooter am 28. August 2015 Open Air auf der Trabrennbahn Bahrenfeld Der nächste Hamburger Kultursommer wird heiß – Scooter ist bestätigt! Die Techno- Pioniere bilden nicht nur eine der erfolgreichsten deutschen Bands überhaupt. Das Trio um Tausendsassa H.P. Baxxter ist die Garantie dafür, dass alle abgehen werden wie eine Rakete. Wenn die Hamburger Lokalmatadoren im nächsten Jahr am 28. August auf die Bühne der Trabrennbahn Bahrenfeld treten werden, wird die Stadt zu Beben beginnen! Am 26. September erschien das neue Album von Scooter, „The Fifth Chapter“. Darauf wagt die Band im 20. Jahr ihres Bestehens noch einmal alles. Die Platte klingt durchweg modern, es ist ein von subtiler, bisweilen dadaistischer Selbstironie durch- drungenes Album, bei dem nicht, wie so oft in der Vergangenheit, von Single zu Single geschritten wird, sondern das wie ein klassisches Pop-Album einen echten Spannungsbogen besitzt – die Band bleibt sich bei ihrem mittlerweile 17. Studioalbum natürlich trotzdem treu. Eine Generalüberholung ist nötig gewesen. Der Abschied von Gründungsmitglied Rick J. Jordan hatte eine klaffende Lücke im Bandgefüge hinterlassen. H.P. Baxxter sah sich als „Maximo Leader“ und einziges verbliebenes Mitglied der Ur-Besetzung mit einem Mal mit noch größerer musikalischer Autorität ausgestattet als zuvor. 23 Top Ten-Hits, 30 Millionen verkaufte Tonträger und über 90 Gold- und Platin-Awards weltweit – besser geht es eigentlich nicht, was soll da noch kommen? H.P. fand mit Phil Speiser als dritten im Bunde und an den Synthesizern einen neuen Mitstreiter, der sich so stark in der Gegenwart der Produktionstechnik bewegte, dass jedes Arbeiten an einem neuen Track zu einem Sparring wie beim Boxen wurde. -

Un Intento De Diálogo. Los Relatos De Inkarri Y Del Pishtaco En Rosa Cuchillo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cybertesis UNMSM UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL MAYOR DE SAN MARCOS FACULTAD DE LETRAS Y CIENCIAS HUMANAS UNIDAD DE POSGRADO Un intento de diálogo. Los relatos de Inkarri y del pishtaco en Rosa cuchillo TESIS Para optar el Grado Académico de Magíster en Literatura Peruana y Latinoamericana AUTOR Hardy ROJAS PRUDENCIO ASESOR Gonzalo ESPINO RELUCÉ Lima – Perú 2017 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN…………………………………………………………………………4 CAPÍTULO I ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN…………………………………………………………….7 1.1 El aspecto mítico y mesiánico en Rosa Cuchillo……………………………….....9 1.2 La integración y el conflicto en Rosa Cuchillo…………………………………....13 1.3 El Informe sobre Uchuraccay y Lituma en los Andes…………………………...19 CAPÍTULO II MARCO TEÓRICO………………………………………………………………………31 2.1. La identidad cultural………………………………………………………………..31 2.2. La etnicidad…………………………………………………………………………37 2.3. La construcción del Otro…………………………………………………………...41 2.4. El cuerpo como objeto de castigo………………………………………………...45 2.5. La racionalidad andina…………………………………………………………….49 2.5.1. La relacionalidad andina……………………………………………………53 2.5.2. La complementariedad……………………………………………………...54 2.5.3. La reciprocidad……………………………………………………………….56 2.5.4. Categorías andinas…………………………………………………………58 2.5.4.1. Runa…………………………………………………………………..58 2.5.4.2. Tinkuy…………………………………………………………………61 2.5.4.3. Yanantin………………………………………………………………65 2 2.5.4.4. Pachacuti……………………………………………………………..69 CAPÍTULO III INKARRI Y EL NAKAQ.….……………………………………………………………..73 3.1. Inkarri………………………………………………………………………………...75 3.1.1. La utopía andina………………………………………………………………75 3.1.2. La formación del mito de Inkarri……………………………………………..79 3.1.2.1. Juan Santos Atahualpa………………………………………………..93 3.1.2.2. Túpac Amaru II…………………………………………………………97 3.1.3. La separación en el mito de Inkarri……………………………………….102 3.2. -

Staging Lo Andino: the Scissors Dance, Spectacle, and Indigenous Citizenship in the New Peru

Staging lo Andino: the Scissors Dance, Spectacle, and Indigenous Citizenship in the New Peru DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason Alton Bush, MA Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Co-Advisor Katherine Borland, Co-Advisor Ana Puga Copyright by Jason Bush 2011 Abstract “Staging Lo Andino: Danza de las Tijeras, Spectacle, and Indigenous Citizenship in the New Peru,” draws on more than sixteen months of fieldwork in Peru, financed by Ohio State‟s competitive Presidential Fellowship for dissertation research and writing. I investigate a historical ethnography of the Peruvian scissors dance, an acrobatic indigenous ritual dance historically associated with the stigma of indigeneity, poverty, and devil worship. After the interventions of Peruvian public intellectual José María Arguedas (1911-1969), the scissors dance became an emblem of indigenous Andean identity and valued as cultural patrimony of the nation. Once repudiated by dominant elites because it embodied the survival of indigenous spiritual practices, the scissors dance is now a celebrated emblem of Peru‟s cultural diversity and the perseverance of Andean traditions in the modern world. I examine the complex processes whereby anthropologists, cultural entrepreneurs, cosmopolitan artists, and indigenous performers themselves have staged the scissors dance as a symbolic resource in the construction of the emergent imaginary of a “New Peru.” I use the term “New Peru” to designate a flexible repertoire of utopian images and discourses designed to imagine the belated overcoming of colonial structures of power and the formation of a modern nation with foundations in the Pre-Columbian past. -

La Figura Del Pishtaco Andino Como

Estudios Latinoamericanos 39 (2019) 131–141 https://doi.org/10.36447/Estudios2019.v39.art8 La fi gura del pishtaco andino como expresión simbólica de trauma social, aculturación y confl icto (ss. XVI-XXI) Mirosław Mąka , Elżbieta Jodłowska Resumen El pishtaco andino es una de las fi guras más intrigantes y difíciles de defi nir dentro del imaginario po- pular. No cabe en ninguna de las categorías de seres sobrenaturales presentes en el universo de las creen- cias de los pueblos andinos. Crea su categoría propia, autónoma, que genéticamente radica tanto en la realidad histórica de las primeras décadas de la conquista, como en la mitología autóctona. Constituye una conceptualización y visualización de la trauma cultural muy profunda y fruto de su tratamiento sicológico que ha atribuido una cara y una fi gura a las amenazas existenciales nuevas. El temor ante lo desconocido implicaría un estado de desamparo y, en cambio, el temor ante un enemigo conocido permite elaborar una estrategia de defensa. En la mitología milenarista andina del periodo siguiente a la Conquista el pishtaco apareció como una fi gura simbólica personalizando al enemigo que va a desa- parecer solo cuando se reaviva el imperio Inca idealizado. El pishtaco no viene dotado de una sola cara o un solo aspecto. En los últimos 500 años aparecía llevando vestido de convento, del hacendado cruel, de un soldado, de un médico o cualquiera otro a quien los campesinos hubiesen reconocido como „ajeno”. Las visualizaciones más antiguas que se han descrito ya en el siglo XVI siguen siendo vivas y le suceden, sobreponiéndose a ellas, las visualizaciones siguientes, creadas más tarde. -

Un Intento De Diálogo. Los Relatos De Inkarri Y Del Pishtaco En Rosa Cuchillo

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL MAYOR DE SAN MARCOS FACULTAD DE LETRAS Y CIENCIAS HUMANAS UNIDAD DE POSGRADO Un intento de diálogo. Los relatos de Inkarri y del pishtaco en Rosa cuchillo TESIS Para optar el Grado Académico de Magíster en Literatura Peruana y Latinoamericana AUTOR Hardy ROJAS PRUDENCIO ASESOR Gonzalo ESPINO RELUCÉ Lima – Perú 2017 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN…………………………………………………………………………4 CAPÍTULO I ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN…………………………………………………………….7 1.1 El aspecto mítico y mesiánico en Rosa Cuchillo……………………………….....9 1.2 La integración y el conflicto en Rosa Cuchillo…………………………………....13 1.3 El Informe sobre Uchuraccay y Lituma en los Andes…………………………...19 CAPÍTULO II MARCO TEÓRICO………………………………………………………………………31 2.1. La identidad cultural………………………………………………………………..31 2.2. La etnicidad…………………………………………………………………………37 2.3. La construcción del Otro…………………………………………………………...41 2.4. El cuerpo como objeto de castigo………………………………………………...45 2.5. La racionalidad andina…………………………………………………………….49 2.5.1. La relacionalidad andina……………………………………………………53 2.5.2. La complementariedad……………………………………………………...54 2.5.3. La reciprocidad……………………………………………………………….56 2.5.4. Categorías andinas…………………………………………………………58 2.5.4.1. Runa…………………………………………………………………..58 2.5.4.2. Tinkuy…………………………………………………………………61 2.5.4.3. Yanantin………………………………………………………………65 2 2.5.4.4. Pachacuti……………………………………………………………..69 CAPÍTULO III INKARRI Y EL NAKAQ.….……………………………………………………………..73 3.1. Inkarri………………………………………………………………………………...75 3.1.1. La utopía andina………………………………………………………………75 3.1.2. La formación del mito de Inkarri……………………………………………..79 3.1.2.1. Juan Santos Atahualpa………………………………………………..93 3.1.2.2. Túpac Amaru II…………………………………………………………97 3.1.3. La separación en el mito de Inkarri……………………………………….102 3.2. El pishtaco o nakaq: formación y análisis……………………………………...112 CAPÍTULO IV INKARRI ANTE LA IDEOLOGIA DEL NAKAQ EN ROSA CUCHILLO………….120 4.1.