Tarantino V. Gawker: the News, Hyperlinking, and Contributory Infringement Liability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,626,915 B2 Uchida (45) Date of Patent: Jan

US008626915B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,626,915 B2 Uchida (45) Date of Patent: Jan. 7, 2014 (54) ROUTING METHOD 2006/0059279 A1* 3/2006 KakiZaki ....................... .. 710/33 2007/0162749 A1 7/2007 Lim (75) Inventor: Yoshiaki Uchida, Kawasaki (JP) 2007/0174501 A1 * 7/2007 Lln et a1‘ """""""""""" " 710/15 (73) Assignee: Fujitsu Limited, Kawasaki (JP) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( * ) Notice: patentSubject' is to extendedany disclaimer, or adjusted the term under of this 35 JP 2002-312316 :2 10/2002 U.S.C. 15405) by 0 days. JP 2003-122615 4/2003 JP 2004-185312 7/2004 (21) Appl' NO". 12/766’017 JP 2006-0854012005-130214 3/20065/2005 . JP 3994126 10/2007 WO 00/22796 4/2000 (65) Prior Publication Data WO 2004/ 100456 A1 11/2004 Us 2010/0205300 A1 Aug. 12, 2010 OTHER PUBLICATIONS _ _ International Search Report for PCT/ J P2007/ 070796, mailed on Mar. Related US. Application Data 18, 2008' (63) Continuation of application No. PCT/JP2007/070796, Chinese Of?ce APP?“ issued Aug 24, 2012 in Corresponding Chi ?led on Oct 25 2007 nese Patent Application No. 2007801012733. ' ’ ' Chinese Of?ce Action mailed Mar. 7, 2013 for corresponding Chi (51) Int Cl nese Application No. 2007801012733. ' ' Extended European Search Report dated Feb. 17, 2012 issued in G06F 15/1 73 (200601) corresponding European Patent Application No. 078305307. (52) U-s- Cl- Chinese Of?ce Action issued May 15, 2012 issued in corresponding USPC ......................................... .. 709/225; 709/224 Chinese Patent Application No. 2007801012733. (58) Field of Classi?cation Search _ _ USPC ............... -

Volume CXXVI, Number 2, October 3, 2008

The LAWRENTIAN SPORTS FEATURes OP/ED A&E 12 VARIETY FRIDAY, OCTOBER 3 2008 Women's tennis continues Adam Brody drops by Staff ed: giving Lawrentians a Abstract artist tackles new conference dominance Lawrence experience technique THE >> page 10 >> page 3 >> page 7 >> page 9 What’s on your iPod?: Drew Baumgartner LAWRENTIAN 1. “Young Lovers in Town,” The 3. “Between the Devil and the Deep I heard their version, realized I had band comes in. It’s magic. FRIDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2008 Bottle Rockets Blue Sea,” George Harrison always loved the song, and decided Editor in Chief: This song reads more like a joke George must have been on a mis- it was about damn time. 8. “Stepfather Factory,” El-P Dorothy Wickens than any of the other Bottle Rocket’s sion to record the cutest arrange- This isn’t the greatest track, but Business Manager stuff I know. The lyrics seem totally ment of this song possible. It’s pure 6. “Bedlam,” Elvis Costello the production here is incredible. Christie McCowen mismatched with the boozy, bar- sap, from the tuba and ukulele to I might be the only Costello fan If everyone were making beats like room atmosphere until you get to the way he sings the word “twist”, who actually enjoys this album, and this, the world would be a better News Editor: that last line. but I love it. even I’ll admit it has its slow parts, place. Katy Hillbo VOL. CXXTHEVI, NO. 2 LAWRENLAWRENCE UNIVERSITY'S STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1884 TIANWWW.LAWRENTIAN.COM but it’s tracks like this that prove 2. -

Holidays? Indie Retailers Believe They'll Survive the Season

Hap Holidays? Indie Retailers Believe They'll Survive The Season By all rights, indie record store owners should be chasing Prozac with shots of gin. After all, analysts were predicting that Nov. 28 would be the Blackest Friday of them all (Billboard, Dec. 6). True, the numbers weren't good. But some of the retailers I spoke to are cautiously optimistic. Part of this may be due to the fact that indies traditionally see stronger sales closer to Christmas. "Black Friday has not been a big dynamic here," says Todd Robinson, president of the Indi- anapolis store Luna. "For us, it is closer to the holiday-when been doing well selling vinyl and record For the record: Sonic Boom (left) people start getting their lists together players, but now nontraditional stores are and Hot Poop The and stock at chain locations starts to also starting to carry them." music," McGuinn says, pointing out dwindle -that we get super busy." While Mendez is worried that bigger that his biggest sellers have been Indies "Our biggest sales will come the stores take his sales, other retailers happily Enya, II Divo and the album "Two CORTNEY week before Christmas," adds Jim report seeing the opposite. Men With the Blues" by Wynton HARDING McGuinn, owner of Hot Poop in Walla "We have more people traveling to the store now from other Marsalis and Willie Nelson. Walla, Wash. parts of Long Island," says Karl Groeger, owner of Looney Tunes Appealing to purists also seems to work for John Henderson, Let's hope he's right. -

THE TUFTS DAILY NEWS | FEATURES Wednesday, November 30, 2005

THE TUFTS Where You Read It First VOLUME L, NUMBER 55 DAILY WEDNESDAY,NOVEMBER 30, 2005 Oh, the places they will go: ROTC seniors get placements BY BRIAN MCPARTLAND Officer Qualifying Test, similar to the SAT Senior Staff Writer but with added sections for pilot and navi- gator topics. The test includes questions on As some seniors go to career fairs for spatial reasoning and asks students to draw finance and others go to fairs for communi- maps. cations, one group of students is headed Dixon took the test in February of her someplace else entirely after graduation: the sophomore year and applied for the pilot U.S. Armed Forces. and navigator programs. Her score qualified In the past couple of weeks, students in her to become a navigator, an eight-year the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) commitment. program have begun to receive their post- She applied for a position in personnel, graduation assignments. though, and received her first choice last Senior Caroline Kennedy will be going April. She was also assigned her third choice into military intelligence in the Army — her location, RAF Mildenhall which is 70 miles first choice. ROTC participants send their outside of London. “I specified that I wanted choices and applications to ROTC head- to be assigned to a base overseas,” she said. quarters for their branch of the military: Dixon applied for a postponement of her Army, Navy or Air Force. Marine Corps stu- active duty to attend graduate school in dents go through the Navy ROTC. community health, and she said she will Kennedy will spend 18 weeks in Ft. -

Firemon-Security-Automation-101

Security Automation 101: Change Management and the Complexity Gap The result is a complexity gap where emerging network and cloud technologies outpace security teams’ ability to secure and manage their expanding enterprise perimeters. Executive Summary FAST FACTS: Today’s threat landscape is constantly evolving. expanding enterprise perimeters. Organizations • The rapid pace of digital transformation demands Sophisticated cyber threats are becoming smarter find themselves at a crossroads – they must ensure error-prone network security processes be automated. and faster, leading to an increase in security that security doesn’t slow down innovation and that • It is increasingly difficult to maintain consistent, breaches and unprecedented fines for non- innovation doesn’t compromise security. Closing continuous compliance of network security compliance. Simultaneously, organizations are the complexity gap at scale requires automation of devices from multiple vendors and eliminate costly rushing to embrace digital transformation, driven network security functions to replace manual, error- misconfigurations caused by human error. by emerging technologies like mobility, cloud prone processes, maintain regulatory and internal computing, large-scale virtualization, software- compliance, and reduce overall security risk. This • Security policy enforcement points are not only a defined networking, and the hyperconnected will increase the efficiency and efficacy of security vital part of the network security architecture, they Internet of Things. Yet, organizations worldwide teams, drive business innovation, and improve the are growing in criticality as networks expand in face an inability to hire and retain skilled security bottom line. scope and complexity across multiple environments. professionals, putting additional strain on lean This eBook describes how the complexity gap • An intelligent network security platform will provide security teams and increasing their security risk. -

YDC Checks out the Occupy DC Scene Kathy Zhang in Both Movements, People Protesting Were Young D.C

In this issue Entertainment 8–9 After Penn State scandal, Lifestyle 4–7 YDC checks out laws that News 1–3 say who must report cases Breaking Dawn– On the Street 12 Is it really PG-13? Soapbox 11 of child abuse p. 8 Viewpoints 10 p. 3 Volume 21 issue 3 November 2011 YDC checks out the Occupy DC scene Kathy Zhang In both movements, people protesting were Young D.C. mistreated and called names. Protesters in each said Employees, frustrated consumers and even they were not earning fair wages. Although occupi- students have taken to the streets to rally against ers have sustainable laws protecting their right to greed. This movement has captured the spotlight free speech compared to the South during the Civil in the news, the eye of the American public, even Rights movement, protests sometimes have gotten though that was not always the case. out of hand and the police came in overreacting and The ideas of Occupy Wall Street made its way making numerous arrests. to Washington, D.C. Oct. 1, two weeks after the There are two established “occupy” locations protesters rallied and stayed in Zuccotti Park in in D.C: one on Freedom Plaza (Pennsylvania Ave- New York. The protests first started with an activist nue N.W. between 13th and 14th Streets) and the group, Adbusters, which opposes consumerism, one in McPherson Square (15th and K Streets, corporate greed and the unequal distribution of NW), both urban downtown areas. Freedom Plaza wealth. Adbusters is also the name of the group’s occupants call themselves Stop the Machine and magazine, which is published in Canada. -

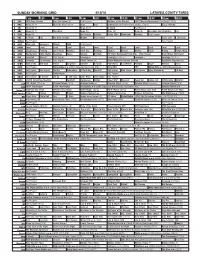

Sunday Morning Grid 4/10/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/10/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Nicklaus at the Masters 2016 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Gymnastics Pacific Rim Championships. (Taped) Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Brain Maker With David 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef Paid Program Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 3 › (1997, Comedia) Alex D. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

Cover me, men Syke takes classic rock to Myrtle Creek’s Music in the Park JULY 13-19, 2012 CURRENTS The News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/5 Movies/7 Book Review/11 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, July 12, 2012 5541-672-338341-672-3383 LARGEST FURNITURE & MATTRESS SHOWROOMS WITH PRODUCTS MADE IN THE USA! Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, July 12, 2012 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING ROSEBURG returns to Half Shell for a fourth time. Hot 100 singer REAL AP-PEAL Bell first performed there as an opener for Etta James in plays The Zoo 2006. Rock musician Uncle Since then, he has been a Kracker will perform July 21 finalist on the NBC reality at The Zoo. show “The X-Factor.” Kracker, 38, is best known All shows are free and start for the songs “Smile,” “Drift at 7 p.m. Away” and “Follow Me.” The Information: 541-677-1708 latter reached number five on or www.halfshell.org. the Billboard Top 100 in 2001. Kracker has released five albums since 2000. ROSEBURG The performance begins at Mark Chesnutt 5:30 p.m. at 2455 N.E. Dia- mond Lake Blvd., Roseburg. plays at The Zoo Tickets are $25 plus a $1.87 Country music singer Mark processing fee. Tickets can be Chesnutt will perform at The purchased through Zoo on Friday. www.zooroseburg.com. Chesnutt, 48, has recorded Information: 541-672-4488. multiple U.S. Billboard Hot Country Songs, including eight ROSEBURG No. -

Arqueologia Do

1 2 SUMÁRIO SONORIDADES NOVAS TECNOLOGIAS E ESTETICAS Introdução à arqueologia da escuta - Do som e da voz como objetos de 7 1 enunciação Ivan Capeller Sonoridades, música e mobilidade: um estudo sobre as novas práticas 16 2 tecnológicas baseadas na espacialização e nos dispositivos móveis Diego Brotas Schizophonia digital: explorações da condição da música na cibercultura 27 3 Rafael Dupim Souza O Admirável mundo da tecnologia musical: Do fonógrafo ao MP3, a 37 4 funcionalidade do gênero para a comunicação da música Nadja Vladi “Cada um com seu iPod” - A escuta de In Rainbows, do Radiohead 50 5 Jorge Cardoso Filho Por uma Economia Política do Funk Carioca - Notas sobre a teoria pós- 6 moderna e seus desdobramentos na música popular contemporânea Pablo Laignier Música Popular Brasileira no contexto das tecnologias digitais: a produção 7 independente e a emergência de novas estratégias e representações sobre as identidades musicais Thiago Pires Galletta VideoSongs da banda Pomplamoose: o que você vê é o que você ouve 88 8 Marcelo Bergamin Conter e Alexandre Rocha da Silva 3 Indústria fonográfica X novas plataformas musicais - Trânsitos sonoros na 101 9 era da Internet Tatiana Rodrigues Lima Sonoridade - elemento integrante da linguagem e cultura radiofônica 113 10 Graziela Bianchi Rádio na Web - Um novo modelo de comunicação radiofónica 124 11 Nair Silva O novo rádio: um estudo sobre a tecnologização da redação em uma 135 12 emissora comunitária de interior Debora Cristina Lopez e Roscéli Kochhann Som e complexidade urbana: apontamentos a partir de uma visão sistêmica 146 13 das sonoridades do comércio popular no Hipercentro de Belo Horizonte Juliana O. -

The New Album Sol -Angel and the Hadley St

EXCLUSIVE :°ORMATS IN FLUX New Study Tracks Format -By- LEGAL: The Fairness Doctrine: Format Impact In Initial Transition 2009 Redux? To PPM Ratings From Diary PROFILES Rubber City's Tom Mandel Gets Business Done By DIAMOND `RING' Keeping It Local Beyoncé Earns A Fourth IMAGING: Is Your On -Air Messaging No. 1 At Mainstream Authentic? r R &B /Hip -Hop, As & 'Ladies (Put A Ring RADIO RECORDS WEB: Pay Attention To Your Stream, On It)' Bounds 2 -1 Because Your Listeners Are NOVEMBER 28, 2008 NO. 1790 $6.50 www.RadioandRecords.com ADVERTISEMENT Featuring the #1 selling single "I DECIDED" . and the hot tracks "T.O.N.Y" & 'Sandcastle Disco" IOW Album Contributions by The Neptunes, Cee -Lo, Mark Ronson, Lamont Dozier, www.solongemusic.com . ßilal, and more. www.hodleystreetjournol.com a ..«. GEFFEN www.myspoce.com/solonge The New Album Sol -Angel and the Hadley St. Dreams Available Now! www.americanradiohistory.com MORE LISTENERS. MORE MONEY. MORE BUZZ. INSTANTLY. Introducing a revolutionary new way to create instant listeners, drive instant revenue and generate instant local market buzz. if.net gives your station access to super -hot national contests built for the local level. Superbowl tickets, exclusive trips to the Playboy mansion, walk -on roles in TV shows like MADtv and Bones; modeling contracts with top agencies...and much more. if.net's unique contest engine also allows you to make money by running your own turnkey contests. CBS Radio has already gotten started. You can too! Contact Henry Mowry at Radio & Records to find out how. Email hmowry @radioandrecords.com, or call him at 323 -954 -3424. -

(EW-201339) Innovative Acoustic Sensor Technologies for Leak Detection in Challenging Pipe Types

(EW-201339) Innovative Acoustic Sensor Technologies for Leak Detection in Challenging Pipe Types December 2016 This document has been cleared for public release; Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE (SF 298) OMB No. 0704-0811 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information, it if does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. -

Grayzone - Quarterly Digest - July 2002

GrayZone - Quarterly Digest - July 2002 . GrayZone Quarterly Digest July 2002 Headline News | Artist's Corner | Busts | WorldWide Update | Legal Beagle Napster Files Chapter 11 Napster, Inc., which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection recently, won final approval June 25, 2002 of a $5.13 million debtor-in-possession (DIP) agreement with Bertelsmann AG, its prospective purchaser. Napster will use $4 million of the loan to fund business operations. The remaining $1.13 million will finance a key employee retention plan, the terms of which were also approved on June 25. Napster first stirred controversy as the provider of a free Internet music service that allowed millions of music fans to download and swap copyright music for free. Eventually the legitimate music industry was able to convince the courts that Napster's business model was illegal. Napster, which currently has a staff of 18, indicated it would rehire up to 28 additional employees once it received the DIP funding. The loan includes an 8% interest rate and expires the earliest of August 30, 2002, the completion of the sale, or the termination of the sale agreement. Napster has reportedly said that Bertelsmann is its only hope for a sale in Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Bertelsmann has agreed to acquire Napster's assets for $8 million in cash plus the elimination of its alleged $83 million secured claim. Napster filed for bankruptcy protection on June 3, listing assets of $7.9 million and liabilities of $101 million, as of April 30. Those suing Napster may now seek settlement through the bankruptcy proceedings. Although it is possible that the recording industry may not recoup all or any of its losses from the blatant and widespread copyright violations that occurred at Napster on a routine basis, experts said the recording industry was victorious nonetheless.