Hollywood's Hero-Lawyer: a Liminal Character and Champion of Equal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

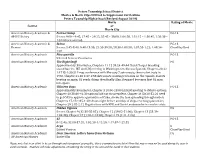

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

Book Review in the Novel- the Firm by John Grisham

Republic of the Philippines Surigao Del Sur State University Tandag, Surigao Del Sur BOOK REVIEW IN LITERATURE 2 ( THE FIRM ) Submmited by: Ermie Jane R. Otagan (BEED-IV) Submmited to: Ms. Lady Sol Azarcon-Suazo (Instructor) OCTOBER 2011 Title : THE FIRM About the Author John Ray Grisham, Jr. (born February 8, 1955) is an American author, best known for his popular legal thrillers. John Grisham graduated from Mississippi State University before attending the University of Mississippi School of Law in 1981 and practiced criminal law for about a decade. He also served in the House of Representatives in Mississippi from January 1984 to September 1990. Beginning writing in 1984, he had his first novel A Time To Kill published in June 1989. As of 2008, his books had sold over 250 million copies worldwide. A Galaxy British Book Awards winner, Grisham is one of only three authors to sell two million copies on a first printing, the others being Tom Clancy and J. K. Rowling. Early life and education John Grisham, the second oldest of five siblings, was born in Jonesboro, Arkansas, to Wanda Skidmore Grisham and John Grisham. His father worked as a construction worker and a cotton farmer, while his mother was a homemaker. When Grisham was four years old, his family started traveling around the South, until they finally settled in Southaven in DeSoto County, Mississippi. As a child, Grisham wanted to be a baseball player. Despite the fact that Grisham's parents lacked formal education, his mother encouraged her son to read and prepare for college. -

Book Review on the Novel the Firm Written by John Grisham

BOOK REVIEW ON THE NOVEL THE FIRM WRITTEN BY JOHN GRISHAM A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For S-1 Degree in American Studies In English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Novin Nur Pratiwi NIM: 13020111120006 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2018 PRONOUNCEMENT I honestly confirm that I compile this book review project by myself and without taking any results from other researchers in S-1, S-2, S-3 and in diploma degree of any university. I ascertain also that I do not quote any material from other publications or someone’s paper except from the references mentioned. Semarang, July 2018 Novin Nur Pratiwi MOTTO AND DEDICATION “Jika Allah menolong kamu, maka tidak akan ada yang mengalahkan kamu” (TQS.Ali Imran : 160) This final project is dedicated to people who support me in every single moment, especially my beloved grandmother and my mother. BOOK REVIEW ON THE NOVEL THE FIRM WRITTEN BY JOHN GRISHAM Written by Novin Nur Pratiwi NIM : 13020111120006 is approved by project advisor on 24 July 2018 Project Advisor Dra. Christina Resnitriwati, M. Hum NIP. 195602161983032001 The Head of the English Department Dr. Agus Subiyanto, M.A. NIP. 196408141990011001 VALIDATION Approved by Strata 1 Thesis Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University on August 2018 Chair Person First Member Retno Wulandari, S.S.,M.A Drs. Jumino, M.Lib.,M.Hum NIP. 19750525 200501 2 002 NIP. 19620703 199001 1 001 Second Member Third Member Rifka Pratama, S.Hum.,M.A Dwi Wulandari, S.S.,M.A NPPU. H. -

CHAPTER 3 MITCH's ARTFULNESS This Chapter Will Discuss About

M a d z k u r | 15 CHAPTER 3 MITCH’S ARTFULNESS This chapter will discuss about Mitch’s characteristic which is focused on Mitch’s artfulness portrayed in the novel, then how his artfulness helps him to solve his problems. But, before the researcher tries to find out Mitch’s artfulness which can help him to solve the problems, the researcher would like to understand first how he is described in the novel. From the description, the researcher would be able to understand how Mitch solves the problems in the story by his characteristic and personality. 3.1.The Description of Mitch’s Artfulness Rule in his Character Evidence stated that character consists of the individual patterns of behavior and characteristics which make up and distinguish one person from another (1). Therefore, it can be understood that each person has a different character, because the main function of the character is to distinguish between one people to another. Such like the main character in Grisham’s The Firm, Mitchell Y. McDeere. digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id M a d z k u r | 16 Mitchell Y. McDeere, or used to call as Mitch is the male main character in the novel. He was introduced as an artful person. Definitely, there are some indications or visible image about him which made him looked like an artful person. Therefore, in this section the researcher tries to find out those indications. -

Law and Resistance in American Military Films

KHODAY ARTICLE (Do Not Delete) 4/15/2018 3:08 PM VALORIZING DISOBEDIENCE WITHIN THE RANKS: LAW AND RESISTANCE IN AMERICAN MILITARY FILMS BY AMAR KHODAY* “Guys if you think I’m lying, drop the bomb. If you think I’m crazy, drop the bomb. But don’t drop the bomb just because you’re following orders.”1 – Colonel Sam Daniels in Outbreak “The obedience of a soldier is not the obedience of an automaton. A soldier is a reasoning agent. He does not respond, and is not expected to respond, like a piece of machinery.”2 – The Einsatzgruppen Case INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 370 I.FILMS, POPULAR CULTURE AND THE NORMATIVE UNIVERSE.......... 379 II.OBEDIENCE AND DISOBEDIENCE IN MILITARY FILMS .................... 382 III.FILM PARALLELING LAW ............................................................. 388 IV.DISOBEDIENCE, INDIVIDUAL AGENCY AND LEGAL SUBJECTIVITY 391 V.RESISTANCE AND THE SAVING OF LIVES ....................................... 396 VI.EXPOSING CRIMINALITY AND COVER-UPS ................................... 408 VII.RESISTERS AS EMBODIMENTS OF INTELLIGENCE, LEADERSHIP & Permission is hereby granted for noncommercial reproduction of this Article in whole or in part for education or research purposes, including the making of multiple copies for classroom use, subject only to the condition that the name of the author, a complete citation, and this copyright notice and grant of permission be included in all copies. *Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba; J.D. (New England School of Law); LL.M. & D.C.L. (McGill University). The author would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in reviewing, providing feedback and/or making suggestions: Drs. Karen Crawley, Richard Jochelson, Jennifer Schulz; Assistant Professor David Ireland; and Jonathan Avey, James Gacek, Paul R.J. -

Domestication in Contemporary Polish Dubbing Urszula Leszczyńska, University of Warsaw, and Agnieszka Szarkowska, University of Warsaw/University College London

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 30 – July 2018 “I don't understand, but it makes me laugh.” Domestication in contemporary Polish dubbing Urszula Leszczyńska, University of Warsaw, and Agnieszka Szarkowska, University of Warsaw/University College London ABSTRACT Despite being (in)famous for its use of voice-over in fiction films, Poland also has a long- standing dubbing tradition. Contemporary Polish dubbing is largely domesticated: culture- bound items from the original are often replaced with elements of Polish culture, which is supposed to increase viewers’ enjoyment of the film. In this study, we examined whether Polish viewers can identify references to Polish culture in the contemporary Polish dubbing of foreign animated films and whether they enjoy them. With this goal in mind, we conducted an online survey and tested 201 participants. Given that many references relate to items from the near or distant past, we predicted that viewers may not fully understand them. The results show that, paradoxically, although viewers do not fully recognise references to Polish culture in contemporary Polish dubbing, they welcome such allusions, declaring that they make films more accessible. The most difficult category of cultural references to identify in our study turned out to be allusions to the canon of Polish literature, whereas the best scores were achieved in the case of references to social campaigns and films. Younger participants had more difficulties in recognising cultural allusions dating from before the 1990s compared to older participants. The vast majority of participants declared they enjoy domestication in contemporary Polish dubbing. KEYWORDS Dubbing, domestication, invisibility, ageing of translation, animated films, audiovisual translation, cultural references. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). -

Tone Parallels in Music for Film: the Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra By

TONE PARALLELS IN MUSIC FOR FILM: THE COMPOSITIONAL WORKS OF TERENCE BLANCHARD IN THE DIEGETIC UNIVERSE AND A NEW WORK FOR STUDIO ORCHESTRA BY BRIAN HORTON Johnathan B. Horton B.A., B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Richard DeRosa, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Murphy, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Jazz Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Horton, Johnathan B. Tone Parallels in Music for Film: The Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra by Brian Horton. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 46 pp., 1 figure, 24 musical examples, bibliography, 49 titles. This research investigates the culturally programmatic symbolism of jazz music in film. I explore this concept through critical analysis of composer Terence Blanchard's original score for Malcolm X directed by Spike Lee (1992). I view Blanchard's music as representing a non- diegetic tone parallel that musically narrates several authentic characteristics of African- American life, culture, and the human condition as depicted in Lee's film. Blanchard's score embodies a broad spectrum of musical influences that reshape Hollywood's historically limited, and often misappropiated perceptions of jazz music within African-American culture. By combining stylistic traits of jazz and classical idioms, Blanchard reinvents the sonic soundscape in which musical expression and the black experience are represented on the big screen. -

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year