A Few Good Men? Don't Look in the Movies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

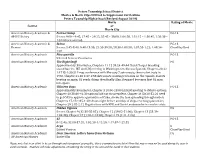

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

Scene and Heard: a Profile of Laura Colella

Scene and Heard: A Profile of Laura Colella She sits quietly in a coffee shop, waiting. She is of small stature, and fine boned. She has striking eyes and a beautiful face, one that easily could be in front of the camera. Providence born and raised, no one she knew ever talked about becoming a filmmaker. She is definitely under the radar – but is soaring very high. This is Laura Colella. In her 44 years, she has managed to impress some very important people in the film world. One of those folks is Paul Thomas Anderson – the same Paul Thomas Anderson who wrote and directed The Master, There Will Be Blood, Boogie Nights and my personal favorite (and I believe his), Magnolia. Last February, he hosted a screening of her film Breakfast with Curtis in LA, and held a lengthy Q & A session afterward. In the same month, at the Independent Spirit Awards, the film was nominated for the John Cassavetes Award for Best Feature made for under $500,000, and won a $50,000 distribution grant from Jameson. Her love of film started early. She grew up heavily involved in theater, was in a few productions at Trinity Rep, and worked there as a production assistant. “My first year in college at Harvard, my boyfriend took me to the end-of-year film screenings at RISD, which opened up that world of possibility for me. I discovered the excellent film department at Harvard, which centered on 16MM production, became totally immersed in it, and never looked back.” Laura now has three features under her belt – Tax Day, her first, for which she received a special equipment grant through the Sundance Institute, portrays two women on their way to the post office on that dreaded day, April 15. -

Law and Resistance in American Military Films

KHODAY ARTICLE (Do Not Delete) 4/15/2018 3:08 PM VALORIZING DISOBEDIENCE WITHIN THE RANKS: LAW AND RESISTANCE IN AMERICAN MILITARY FILMS BY AMAR KHODAY* “Guys if you think I’m lying, drop the bomb. If you think I’m crazy, drop the bomb. But don’t drop the bomb just because you’re following orders.”1 – Colonel Sam Daniels in Outbreak “The obedience of a soldier is not the obedience of an automaton. A soldier is a reasoning agent. He does not respond, and is not expected to respond, like a piece of machinery.”2 – The Einsatzgruppen Case INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 370 I.FILMS, POPULAR CULTURE AND THE NORMATIVE UNIVERSE.......... 379 II.OBEDIENCE AND DISOBEDIENCE IN MILITARY FILMS .................... 382 III.FILM PARALLELING LAW ............................................................. 388 IV.DISOBEDIENCE, INDIVIDUAL AGENCY AND LEGAL SUBJECTIVITY 391 V.RESISTANCE AND THE SAVING OF LIVES ....................................... 396 VI.EXPOSING CRIMINALITY AND COVER-UPS ................................... 408 VII.RESISTERS AS EMBODIMENTS OF INTELLIGENCE, LEADERSHIP & Permission is hereby granted for noncommercial reproduction of this Article in whole or in part for education or research purposes, including the making of multiple copies for classroom use, subject only to the condition that the name of the author, a complete citation, and this copyright notice and grant of permission be included in all copies. *Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba; J.D. (New England School of Law); LL.M. & D.C.L. (McGill University). The author would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in reviewing, providing feedback and/or making suggestions: Drs. Karen Crawley, Richard Jochelson, Jennifer Schulz; Assistant Professor David Ireland; and Jonathan Avey, James Gacek, Paul R.J. -

An Analysis of Boogie Nights and Magnolia Andrew C

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2009 "New" Hollywood Narratives: an Analysis of Boogie Nights and Magnolia Andrew C. Cate Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cate, Andrew C., ""New" Hollywood Narratives: an Analysis of Boogie Nights and Magnolia" (2009). Honors Projects Overview. 23. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/23 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “NEW” HOLLYWOOD NARRATIVES: AN ANALYSIS OF BOOGIE NIGHTS AND MAGNOLIA By Andrew C. Cate An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of Film Studies The School of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2009 Cate 1 “New” Hollywood Narratives: An Analysis of Boogie Nights and Magnolia Introduction To discuss Paul Thomas Anderson the filmmaker is to consider the current age of Hollywood filmmaking and the idea of the “new” Hollywood narrative. As writer- director of such acclaimed films as Magnolia (1999) and There Will Be Blood (2007), Anderson was praised for appearing to have “arrived at his mastery virtually overnight” with his first major release, the 1997 ensemble film Boogie Nights (Gleiberman). Anderson has long been compared to veteran filmmaker Robert Altman, whose take on the typical Hollywood narrative format has clearly influenced Anderson’s films. -

Phantom Thread (2017)

PHANTOM THREAD (2017) ● Released on January 18th, 2018 ● Released on December 25th, 2017 (Limited) ● 2 Hours 10 minutes ● $35,000,000 (estimated) ● Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson ● Written by Paul Thomas Anderson ● Annapurna Pictures, Focus Features, Ghoulardi Film Company ● Rated R for language QUICK THOUGHTS ● Marisa Serafini ● Phil Svitek ● Demetri Panos DEVELOPMENT ● “I remember that I was very sick, just with the flu, and I looked up and my wife (Maya Rudolph) looked at me with tenderness that made me think, “I wonder if she wants to keep me this way, maybe for a week or two.” I was watching the wrong movies when I was in bed, during this illness. I was watching Rebecca, The Story of Adele H., and Beauty and the Beast, and I really started to think that maybe she was poisoning me. So, that kernel of an idea, I had in my mind when I started working on writing something.” ● “Paul will talk about the project early on,” says Sellar. “He’ll show me rough drafts. He’ll show me scenes. I’ll comment. We’ll go back and forth on stuff. We’ll start doing research together. And when he’s got a draft we all feel is good enough to send out to financiers, usually between him and his agent we’ll come up with where we’re going to send it.” - JoAnne Sellar WRITING (Paul Thomas Anderson) ● National Board of Review award for best original screenplay ● Anderson was especially intrigued by a photograph of Dior in a workroom of women dressed in white coats. -

A Few Good Men

A Few Good Men It is perhaps one of the most familiar movie catchphrases in recent history. Jack Nicholson, in full military regalia, sitting in a courtroom, shouting at Tom Cruise. “You can’t handle the truth,” he says. The truth is, the well-known movie A Few Good Men was a stage play first. And it’s back on an area stage at Little Theater of Fall River. Director Kathy Castro notes that she fell in love with the story when the movie came out. “I thought the story was sensational and so relevant; and the acting was great! It would be difficult to say how many times I’ve seen it since. Twenty-plus, easily, and each time, I learn something new. It is a masterful piece of writing, and Aaron Sorkin is a masterful storyteller.” A few years ago, Castro learned of the play version and right away wanted to direct it, putting it before the play selection committee in 2010. She notes that the play comes with great name-recognition, partly due to that already-mentioned catchphrase. The playwright also has something to do with it. Castro notes, “In these ensuing 20 years since the film, Aaron Sorkin has also become quite famous through his work on the TV series, The West Wing and his many Academy-Award nominations and wins for film screenplays. Last year he won for Social Network, and this year he was nominated again for Moneyball.” Having spent more than a year researching in preparation, Castro says she has read everything she could find on the original production of the play in 1988. -

The Golden Age of Porn: Nostalgia and History in Cinema Susanna Paasonen and Laura Saarenmaa

Pornification 19/7/07 10:56 am Page 23 –2– The Golden Age of Porn: Nostalgia and History in Cinema Susanna Paasonen and Laura Saarenmaa The mainstreaming of pornography is indebted to the success of feature-length hardcore films of the 1970s. Shot on 35 mm film, productions such as Deep Throat (1972), Behind the Green Door (1972), The Devil in Miss Jones (1973), The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976) and Debbie Does Dallas (1978) were widely screened both in the USA and internationally. These films have since been estab- lished as classics (Buscombe 2004: 30) and milestones in both scholarly and popular porn historiographies. While some identify the so-called ‘golden age of porn’ through North American legislation and as ranging from 1957 from 1973 (Lane 2000: 22–3), it was in the 1970s and early 1980s that porn shifted towards the mainstream. In a trend titled by the New York Times as porno chic, pornography became fashionable, gained mainstream publicity and popularity (McNair 2002: 62–3; Schaefer 2004: 371; Wyatt 1999). During the past decade, this golden age has been reminisced in films such as People Vs. Larry Flynt (1996), Boogie Nights (1997) and Rated X (2000), numerous documentaries – including the critically acclaimed Inside Deep Throat (2005) – and books.1 This body of popular porn historiography depicts the decade as one of quality films with real stories, personal performers and talented directors, in contrast to the 1980s of video distribution, inflation of the porn industry, rise of AIDS and conservative backlash. With notable exceptions such as the French Le pornographe (2001) and the Spanish–Danish co-production Torremolinos 73 (2003), European histories have not been reminisced to the same degree. -

WHAT I LEARNED at the MOVIES ABOUT LEGAL ETHICS and PROFESSIONALISM by Anita Modak-Truran

WHAT I LEARNED AT THE MOVIES ABOUT LEGAL ETHICS AND PROFESSIONALISM By Anita Modak-Truran HOW I GOT HERE I’ve been fortunate. I practice law. I make movies. I write about both. I took up my pen and started writing a film column for The Clarion-Ledger, a Gannett-owned newspaper, back in the late 90s, when I moved from Chicago, Illinois, to Jackson, Mississippi. (It was like a Johnny Cash song… “Yeah, I’m going to Jackson. Look out Jackson Town….”) I then turned my pen to writing for The Jackson Free Press, an indie weekly newspaper, which provided me opportunities to write about indie films and interesting people. I threw down the pen, as well as stopped my public radio movie reviews and the television segment I had for an ABC affiliate, when I moved three years ago from Jackson to Nashville to head Butler Snow’s Entertainment and Media Industry Group. During my journey weaving law and film together in a non-linear direction with no particular destination, I lived in the state where a young lawyer in the 1980s worked 60 to 70 hours a week at a small town law practice, squeezing in time before going to the office and during courtroom recesses to work on his first novel. John Grisham writes that he would not have written his first book if he had not been a lawyer. “I never dreamed of being a writer. I wrote only after witnessing a trial.” See http://www.jgrisham.com/bio/ (last accessed January 24, 2016). My law partners at Butler Snow have stories about the old days when Mr. -

AFGM Program

JOIN US FOR OUR NEXT PRODUCTION SUNNYBANK THEATRE GROUP PRESENTS sunnybank IN ASSOCIATION WITH ORiGiN THEATRICAL theatre group presents in association with ORiGiN Theatrical box office opens Aug 24 - 10am Sep 20 to Oct 5 A FEW directed by Anne Ross GOOD no sexplease, we’re MENBY AARON SORKIN DIRECTED BY LESLEY DAVIS BRITfor ticketsI Sph 3345H 3964 or www.stg.org.au JULY 26 - AUGUST 11, 2013 e Crew Broadway Production Presented by Brad Wyeth David Brown, Lewis Allen Stage Manager L Robert Whitehead, Roger L. Stevens, Kathy Levin Suntory International Corporation, The Schubert Organisation Stage Manager R Laura May Stinton Stage Crew The Cast Lighting Design Joanne Sephton David Gemmell ** Please be aware that this production contains loud noises, adult themes and language not suitable Costumes Rex Wigney for children Jenny Marshall Pam Cooper Betty Peisley Cathy O’Dowd * Patrons seeking support and information about suicide prevention can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224636. Lighting & Sound Lana Perrin Joanne Sephton Audio Recording Laura May Stinton Set Design Lesley Davis Set Construction Mark Westby Stuart Sephton The action takes place in various locations in Chris O’Leary Washington D.C., and on the United States Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Photography Kayleen Gibson It is Summer, 1986 Erin O’Sheil Program & Media Chris O’Leary Green Room Our wonderful volunteers About the playwright and the play… We would like to thank the following for helping to bring Aaron Benjamin Sorkin (born June 9, 1961) is an Academy and Emmy-award this show to life: winning American screenwriter, producer, and playwright, whose works include A Few Good Men, The American President, The West Wing, Sports Night, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Charlie Wilson's War, The Social Network, Training Ship Norfolk, Wellington Point Moneyball and The Newsroom. -

P. T. Anderson‟S Dilemma: the Limits of Surrogate Paternity

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Sydney Studies P.T. Anderson's Dilemma P. T. Anderson‟s Dilemma: the Limits of Surrogate Paternity JULIAN MURPHET A while ago now, Fredric Jameson located the Utopian dimension of Coppola‟s first Godfather film (1972) in „the fantasy message projected by the title of this film, that is, in the family itself, seen as a figure of collectivity and as the object of a Utopian longing‟.1 In a late-capitalist America beset by an irreversible „deterioration of the family, the growth of permissiveness, and the loss of authority of the father‟, Coppola‟s Sicilians „project an image of social reintegration by way of the patriarchal and authoritarian family of the past‟. (33) To be sure, the ethnic group may preserve within its anachronistic familial webs a relatively untarnished „Name of the Father‟, that can be trotted out for nostalgic wish-fulfilment on celluloid; but it goes without saying that commercial American cinema has always turned on the institution of the family, to the extent that „in a typical Hollywood product, everything, from the fate of the Knights of the Round Table through the October Revolution up to asteroids hitting the earth, is transposed into an Oedipal narrative‟. 2 Jameson‟s Utopian account of the „ineradicable drive towards collectivity‟ (34) betokened by the family drama in American mass culture surely overlooks that most stubborn obstacle to its realization, both within any given plot, and more practically in everyday life: namely, the father himself. -

A Few Words on Word Play by Kenn Finkel

Wordplay Page 1 of 5 A Few Words on Word Play By Kenn Finkel If you’re going to write headlines that attempt to show how hip you are, the pop culture significance has to be connected. That brings up the key to good word play in headlines: It’s that subtle second reference. Using a popular (or ancient) phrase isn’t clever without another level of meaning. It doesn’t take much wit to reach for a word or phrase that you’ve heard on television or in a film or at church or synagogue (or anyplace in the popular lexicon) and to attach it to a headline you’re trying to write — just because that word or phrase (or a variation or oblique reference) appears in the story. Real word play is more subtle than that — and subtlety is one of several keys to writing good headlines. This headline and the first few paragraphs of a commentary piece ran a few years ago: TV networks keep faith in movies about Jesus NEW YORK — When ABC televised the classic Old Testament movie The Ten Commandments on Easter Sunday 1998, some irate viewers complained about the network airing a so-called Jewish movie on the holiest of Christian days. Clearly, religion is not a subject that fosters consensus. Yet, network television — a medium that thrives only by building a consensus of the largest number of viewers possible — is set to broadcast two movies this season that take on the most sensitive of all religious topics, the life of Jesus, and a third on the life of Jesus’ mother, Mary.