The Destino Animatic, and the Fate of Assembling Artistic Truths Into a Greater Whole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

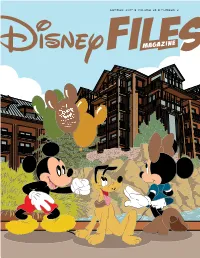

Summer 2017 • Volume 26 • Number 2

sUMMER 2017 • Volume 26 • Number 2 Welcome Home “Son, we’re moving to Oregon.” Hearing these words as a high school freshman in sunny Southern California felt – to a sensitive teenager – like cruel and unusual punishment. Save for an 8-bit Oregon Trail video game that always ended with my player dying of dysentery, I knew nothing of this “Oregon.” As proponents extolled the virtues of Oregon’s picturesque Cascade Mountains, I couldn’t help but mourn the mountains I was leaving behind: Space, Big Thunder and the Matterhorn (to say nothing of Splash, which would open just months after our move). I was determined to be miserable. But soon, like a 1990s Tom Hanks character trying to avoid falling in love with Meg Ryan, I succumbed to the allure of the Pacific Northwest. I learned to ride a lawnmower (not without incident), adopted a pygmy goat and found myself enjoying things called “hikes” (like scenic drives without the car). I rafted white water, ate pink salmon and (at legal age) acquired a taste for lemon wedges in locally produced organic beer. I became an obnoxiously proud Oregonian. So it stands to reason that, as adulthood led me back to Disney by way of Central Florida, I had a special fondness for Disney’s Wilderness Lodge. Inspired by the real grandeur of the Northwest but polished in a way that’s unmistakably Disney, it’s a place that feels perhaps less like the Oregon I knew and more like the Oregon I prefer to remember (while also being much closer to Space Mountain). -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: a Study of the Walt Disney Company’S Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: A Study of The Walt Disney Company's Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11 Lindsay Goddard Senior Thesis presented to the faculty of the American Studies Department at the University of California, Davis March 2021 Abstract Since its founding in October 1923, The Walt Disney Company has en- dured as an influential preserver of fantasy, traditional American values, and folklore. As a company created to entertain the masses, its films often provide a sense of escapism as well as feelings of nostalgia. The company preserves these sentiments by \Disneyfying" danger in its media to shield viewers from harsh realities. Disneyfication is also utilized in the company's responses to cultural shocks and tragedies as it must carefully navigate maintaining its family-friendly reputation, utopian ideals, and financial interests. This paper addresses The Walt Disney Company's responses to two attacks on US soil: the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the attacks on September 11, 200l and examines the similarities and differences between the two. By utilizing interviews from Disney employees, animated film shorts, historical accounts, insignia, government documents, and newspaper articles, this paper analyzes the continuity of Disney's methods of dealing with tragedy by controlling the narrative through Disneyfication, employing patriotic rhetoric, and reiterat- ing the original values that form Disney's utopian image. Disney's respon- siveness to changing social and political climates and use of varying mediums in its reactions to harsh realities contributes to the company's enduring rep- utation and presence in American culture. 1 Introduction A young Walt Disney craftily grabbed some shoe polish and cardboard, donned his father's coat, applied black crepe hair to his chin, and went about his day to his fifth-grade class. -

A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum Alan Bowers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Alan, "FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1921. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1921 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum by ALAN BOWERS (Under the Direction of Daniel Chapman) ABSTRACT In my dissertation inquiry, I explore the need for utopian based curriculum which was inspired by Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center. Theoretically building upon such works regarding utopian visons (Bregman, 2017, e.g., Claeys 2011;) and Disney studies (Garlen and Sandlin, 2016; Fjellman, 1992), this work combines historiography and speculative essays as its methodologies. In addition, this project explores how schools must do the hard work of working toward building a better future (Chomsky and Foucault, 1971). Through tracing the evolution of EPCOT as an idea for a community that would “always be in the state of becoming” to EPCOT Center as an inspirational theme park, this work contends that those ideas contain possibilities for how to interject utopian thought in schooling. -

Heritage Auctions | Winter 2020-2021 $7.9 9

HERITAGE AUCTIONS | WINTER 2020-2021 $7.9 9 BOB SIMPSON Texas Rangers Co-Owner Releases Sweet Nostalgia Enduring Charm Auction Previews Numismatic Treasures Yes, Collectibles Bright, Bold & Playful Hank Williams, Provide Comfort Luxury Accessories Walt Disney, Batman features 40 Cover Story: Bob Simpson’s Sweet Spot Co-owner of the Texas Rangers finds now is the time to release one of the world’s greatest coin collections By Robert Wilonsky 46 Enduring Charm Over the past 12 months, collectors have been eager to acquire bright, bold, playful accessories By The Intelligent Collector staff 52 Tending Your Delicates Their fragile nature means collectible rugs, clothing, scarfs need dedicated care By Debbie Carlson 58 Sweet, Sweet Nostalgia Collectibles give us some degree of comfort in an otherwise topsy-turvy world By Stacey Colino • Illustration by Andy Hirsch Patek Philippe Nautilus Ref. 5711/1A, Stainless Steel, circa 2016, from “Enduring Charm,” page 46 From left: Hank Williams, page 16; Harrison Ellenshaw, page 21; The Donald G. Partrick collection, page 62 Auction Previews Columns 10 21 30 62 How to Bid Animation Art: The Arms & Armor: The Bill Coins: Rare Offering The Partrick 1787 New York-style 11 Ellenshaw Collection Bentham Collection Disney artist and son worked California veterinarian’s Civil Brasher doubloon is one of only seven- Currency: The Del Monte Note on some of Hollywood’s War artifacts include numerous known examples Banana sticker makes bill one greatest films fresh-to-market treasures By David Stone of the most famous -

“I'm Not Walt Disney Anymore!”

hundred competitors, for a special project run jointly by the University Religious Conference and the Ford Foundation 5 to combat the negative image of America in India. It was called, simply, “Project India.” Beginning in 1952, Project India sent twelve students of diverse ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds for nine summer weeks to India, “I’M NOT WALT DISNEY meeting college students, living with their hosts in villages and cities, and hopefully making friends for America. It was ANYMORE!” a kind of precursor to the Peace Corps, which began in the early 1960s. In 1955 I truly felt that I had earned the right to be the second Jewish student selected—to join my friend Sandy Ragins, who later became a rabbi. But I was not chosen, and I wished the ambassadors well as they prepared to depart for India. Less than a week later, I received a call at the ZBT fra- ternity house. It was that “Las Vegas dealer,” Card Walker, At the end of 1965, Walt celebrated his sixty-fourth birthday, asking if I could come to the Walt Disney Studio for the and Roy O. Disney, age seventy-two, began to plan for his interview that would change my life. Surely that trip to India own retirement. The presumptive future CEO, Card Walker, would never have had such a lifelong effect. called me and the Studio’s graphics leader, Bob Moore, to his office. “We have to let the media, our fans, and the enter- tainment industry know that as great a talent as Walt is, he’s not the only creative person at Disney,” Card told us. -

Newsletter. Issue 35 September 2004

Newsletter. Issue 35 September 2004 Inside The Newsletter Welcome to Issue 35 of the club newsletter. th Saturday 25 September 7:30pm Latest Australian Disney News Meeting Join us at this meeting as we look at the many aspects of the World of Disney from Animation, Theme Parks, and The Wonderful World of Disney now on Saturday collectibles. A special look at Disneyland and much more. evenings on Channel 7 at 7.30pm. Come and join us for this exciting meeting. Disney’s Home on the Range – the next Animated feature opens in cinemas on September 23rd. Location: St. Marks Anglican Church Hall. Disney’s The Three Musketeers – Starring Mickey, Cnr. Auburn Rd and Hume Hwy Yagoona. (Near Donald and Goofy is being released on DVD in this month. Bankstown.) Just 150m from the Yagoona Railway Station. Upcoming Club Events The Down Under Disneyana Newsletter is a publication of the Down Under Disneyana Club. th The newsletter is published quarterly and distributed Saturday 25 September 7.30pm to members. Contributions to our newsletter are Join us at this meeting as we look at the wonderful worlds welcome. of Disney. Bring your favourite Disney memory to share. The club address is: Down Under Disneyana Club. PO Box 502 St Marks Anglican Church hall Regents Park, NSW 2143. Cnr Auburn Rd and Hume Hwy Yagoona only 1km along Australia. Auburn Rd from our old meeting location. Down Under Disneyana Club is the Australian Chapter of the National Fantasy Fan Club of the USA, In this newsletter read about the upcoming 50th birthday of and our club is not associated with The Walt Disney Disneyland celebrations. -

Winter 2008 Vol. 17 No. 4

Winter 2008 vol. 17 no. 4 Jada and Lawrence Smith of Florida, Members since 2005, cruise past the construction site of the Treehouse Villas at Disney’s Saratoga Springs Resort & Spa. Illustration by Keelan Parham Disney Files Magazine is published by the good people at Disney Vacation Club If I were to list what I love most about living in Florida P.O. Box 10350 and working for the Mouse, “employer’s liberal use of Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 code names” would have to make my top 10, somewhere behind “sunscreen in January” and slightly ahead of All dates, times, events and prices “humidity in January.” (Just missing the cut: “saltiness of printed herein are subject to turkey legs” and “abundance of white pants.”) change without notice. (Our lawyers Nothing delights middle managers more than sitting do a happy dance when we say that.) around a conference table acting like the room is bugged. MOVING? The rapid dropping of names like “Project Quasar” (Disney’s Update your mailing address Animal Kingdom Villas) and “Project Crystal” (Bay Lake Tower online at www.dvcmember.com at Disney’s Contemporary Resort) can transform any meeting into a scene from Windtalkers (albeit with more nametags and less Nicolas Cage). Of course, not MEMBERSHIP QUESTIONS? all codes are tough to decipher. Case in point: our cloaking of the Treehouse Villas at Disney’s Contact Member Services from Saratoga Springs Resort & Spa with the code name “Project Tarzan.” Not very subtle, but I 9 a.m.-5:30 p.m. Eastern daily at suppose it beats “Project Treehouse.” (800) 800-9800 or (407) 566-3800 You’ll read more about “Project Tarzan” in this edition of your magazine (pages 2-4), but allow me to first introduce a few other key features by revealing their rejected code names. -

THE SORCERER's APPRENTICES: AUTHORSHIP and SOUND AESTHETICS in WALT DISNEY's FANTASIA by Daniel Fernandez a Thesis Submitted

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICES: AUTHORSHIP AND SOUND AESTHETICS IN WALT DISNEY’S FANTASIA by Daniel Fernandez A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2017 Copyright by Daniel Fernandez 2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for all of their guidance and support, especially to my advisor Anthony Guneratne for his helpful suggestions during the writing of this manuscript. I am also grateful to a number of archival collections, particularly those of Yale University for providing me with some of the primary sources used for this manuscript. Likewise, I would like to acknowledge Stephanie Flint for her contribution to the translation of German source material, as well as Richard P. Huemer, Didier Ghez, Jennifer Castrup, the Broward County Library, the University of Maryland, the Fales Library at New York University, and Zoran Sinobad of the Library of Congress, for the advice, material assistance, and historical information that helped shape this project. iv ABSTRACT Author: Daniel Fernandez Title: The Sorcerer’s Apprentices: Authorship and Sound Aesthetics in Walt Disney’s Fantasia Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Anthony Guneratne Degree: Masters of Arts in Communications Year: 2017 This thesis makes three claims new to the critical literature on Walt Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia. Setting the scene by placing a spotlight on the long-serving Philadelphia Orchestra conductor Leopold Stokowski, it contextualizes his pervasive influence, as well as contributions by others that shaped Fantasia and defined the film’s stylistic elements. -

Kent Bingham's History with Disney

KENT BINGHAM’S HISTORY WITH DISNEY This history was started when a friend asked me a question regarding “An Abandoned Disney Park”: THE QUESTION From: pinpointnews [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Tuesday, March 22, 2016 3:07 AM To: Kent Bingham Subject: Photographer Infiltrates Abandoned Disney Park - Coast to Coast AM http://www.coasttocoastam.com/pages/photographer-infiltrates-abandoned-disney-park Could the abandoned island become an OASIS PREVIEW CENTER??? NOTE I and several of my friends have wanted to complete the EPCOT vision as a city where people could live and work. We have been looking for opportunities to do this for the last 35 years, ever since we completed EPCOT at Disney World on October 1, 1983. We intend to do this in a small farming community patterned after the life that Walt and Roy experienced in Marceline, Missouri, where they lived from 1906-1910. They so loved their life in Marceline that it became the inspiration for Main Street in Disneyland. We will call our town an OASIS VILLAGE. It will become a showcase and a preview center for all of our OASIS TECHNOLOGIES. We are on the verge of doing this, but first we had to invent the OASIS MACHINE. You can learn all about it by looking at our website at www.oasis-system.com . There you will learn that the OM provides water and energy (at minimum cost) that will allow people to grow their own food. This machine is a real drought buster, and will be in demand all over the world. This will provide enough income for us to build our OVs in many locations. -

Celebrations-Issue-23-DV24865.Pdf

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World Issue 23 Spaceship Earth 42 Contents all year long with Letters ..........................................................................................6 Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 Celebrations MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic Disney and by Tim Foster............................................................................16 Conservation 52 Explorer Emporium magazine! by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 Receive 6 issues for Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 $29.99* (save more than Interview with Pin Trading & Collecting 56 by John Rick .............................................................................24 15% off the cover price!) Ridley Pearson Disney Cuisine by Allison Jones ......................................................................26 *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United Travel Tips States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. by Beci Mahnken ...................................................................28 Disneyland Magic Oswald the by J Darling...............................................................................30 Lucky Rabbit -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues.