Bayview-Hunters Point Historic Context Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space

IV. Environmental Setting and Impacts H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space Environmental Setting The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department maintains more than 200 parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the City. The City’s park system also includes 15 recreation centers, nine swimming pools, five golf courses as well as tennis courts, ball diamonds, athletic fields and basketball courts. The Recreation and Park Department manages the Marina Yacht Harbor, Candlestick (Monster) Park, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Lake Merced Complex. In total, the Department currently owns and manages roughly 3,380 acres of parkland and open space. Together with other city agencies and state and federal open space properties within the city, about 6,360 acres of recreational resources (a variety of parks, walkways, landscaped areas, recreational facilities, playing fields and unmaintained open areas) serve San Francisco.172 San Franciscans also benefit from the Bay Area regional open spaces system. Regional resources include public open spaces managed by the East Bay Regional Park District in Alameda and Contra Costa counties; the National Park Service in Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties as well as state park and recreation areas throughout. In addition, thousands of acres of watershed and agricultural lands are preserved as open spaces by water and utility districts or in private ownership. The Bay Trail is a planned recreational corridor that, when complete, will encircle San Francisco and San Pablo Bays with a continuous 400-mile network of bicycling and hiking trails. It will connect the shoreline of all nine Bay Area counties, link 47 cities, and cross the major toll bridges in the region. -

Western Legal History

WESTERN LEGAL HISTORY THE JOURNAL OF THE NINTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT HISTORiCAL SOCIETY VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 SUMMER/FALL 1988 Western Legal History is published semi-annually, in spring and fall, by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, P.O. Box 2558, Pasadena, California 91102-2558, (818) 405-7059. The journal explores, analyzes, and presents the history of law, the legal profession, and the courts - particularly the federal courts - in Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Western Legal History is sent to members of the Society as well as members of affiliated legal historical societies in the Ninth Circuit. Membership is open to all. Membership dues (individuals and institutions): Patron, $1,000 or more; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499; Sustaining, $100-$249; Advocate, $50-$99; Subscribing (non- members of the bench and bar, attorneys in practice fewer than five years, libraries, and academic institutions), $25-$49. Membership dues (law firms and corporations): Founder, $3,000 or more; Patron, $1,000-$2,999; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499. For information regarding membership, back issues of Western Legal History, and other Society publications and programs, please write or telephone. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to: Western Legal History P.O. Box 2558 Pasadena, California 91102-2558. Western Legal History disclaims responsibility for statements made by authors and for accuracy of footnotes. Copyright 1988 by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society. ISSN 0896-2189. The Editorial Board welcomes unsolicited manuscripts, books for review, reports on research in progress, and recommendations for the journal. -

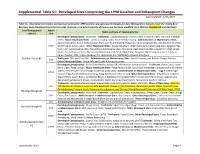

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015 Table S1. Developed sites (name and type) comprising the 1998 baseline and subsequent changes per Bear Management Subunit inside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone (Developed sites that are new, removed, or in which capacity of human-use has been modified since 1998 are highlighted and italicized). Bear Management Admin Name and type of developed sites subunit Unit Developed Campgrounds: Cave Falls. Trailheads: Coyote Meadows, Hominy Peak, S. Boone Creek, Fish Lake, Cascade Creek. Major Developed Sites: Loll Scout Camp, Idaho Youth Services Camp. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Squirrel Meadows Guard Station/Cabin, Porcupine Guard Station, Badger Creek Seismograph Site, and Squirrel Meadows CTNF GS/WY Game & Fish Cabin. Other Developed Sites: Grassy Lake Dam, Tillery Lake Dam, Indian Lake Dam, Bergman Res. Dam, Loon Lake Disperse sites, Horseshoe Lake Disperse sites, Porcupine Creek Disperse sites, Gravel Pit/Target Range, Boone Creek Disperse Sites, Tillery Lake O&G Camp, Calf Creek O&G Camp, Bergman O&G Camp, Granite Creek Cow Camp, Poacher’s TH, Indian Meadows TH, McRenolds Res. TH/Wildlife Viewing Area/Dam. Bechler/Teton #1 Trailheads: 9K1 and Cave Falls. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: South Entrance and Bechler Ranger Stations. YNP Other Developed Sites: Union Falls and Snake River picnic areas. Developed Campgrounds: Grassy Lake Road campsites (8 individual car camping sites). Trailheads: Glade Creek, Lower Berry Creek, Flagg Canyon. Major Developed Sites: Flagg Ranch (lodge, cabins and Headwater Campground with camper cabins, remote cistern and sewage treatment plant sites). Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Flagg Ranch Ranger GTNP Station, Flagg Ranch employee housing, Flagg Ranch maintenance yard. -

Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

SDMS DOCID# 1137835 BAY FILL IN SAN FRANCISCO: A HISTORY OF CHANGE A thesis submitted to the faculty of California State University, San Francisco in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Gerald Robert Dow Department of Geography July 1973 Permission is granted for the material in this thesis to be reproduced in part or whole for the purpose of education and/or research. It may not be edited, altered, or otherwise modified, except with the express permission of the author. - ii - - ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Maps . vi INTRODUCTION . .1 CHAPTER I: JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES OF SAN FRANCISCO’S TIDELANDS . .4 Definition of Tidelands . .5 Evolution of Tideland Ownership . .5 Federal Land . .5 State Land . .6 City Land . .6 Sale of State Owned Tidelands . .9 Tideland Grants to Railroads . 12 Settlement of Water Lot Claims . 13 San Francisco Loses Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 14 San Francisco Regains Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 15 The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Port of San Francisco . 18 CHAPTER II: YERBA BUENA COVE . 22 Introduction . 22 Yerba Buena, the Beginning of San Francisco . 22 Yerba Buena Cove in 1846 . 26 San Francisco’s First Waterfront . 26 Filling of Yerba Buena Cove Begins . 29 The Board of State Harbor Commissioners and the First Seawall . 33 The New Seawall . 37 The Northward Expansion of San Francisco’s Waterfront . 40 North Beach . 41 Fisherman’s Wharf . 43 Aquatic Park . 45 - iii - Pier 45 . 47 Fort Mason . 48 South Beach . 49 The Southward Extension of the Great Seawall . -

Appendix 3-‐1 Historic Resources Evaluation

Appendix 3-1 Historic Resources Evaluation HISTORIC RESOURCE EVALUATION SEAWALL LOT 337 & Pier 48 Mixed-Use Development Project San Francisco, California April 11, 2016 Prepared by San Francisco, California Historic Resource Evaluation Seawall Lot 337 & Pier 48 Mixed-Use Project, San Francisco, CA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Methods ................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Regulatory Framework ....................................................................................................... 3 IV. Property Description ................................................................................................... ….....6 V. Historical Context ....................................................................................................... ….....24 VI. Determination of Eligibility.................................................................................... ……....44 VII. Evaluation of the Project for Compliance with the Standards ............................. 45 VIII. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 58 IX. Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ 59 April 11, 2016 Historic Resource Evaluation Seawall -

DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial

State of California & The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial Page 1 of 32 *NRHP Status Code *Resource Name or # (Assigned by recorder) Potrero Point Historic District D1. Historic Name Potrero Point/Lower Potrero D2. Common Name: Central Waterfront *D3. Detailed Description (Discuss coherence of the district, its setting, visual characteristics, and minor features. List all elements of district.): The Potrero Point Historic District (also referred to as the Central Waterfront) is located in the Potrero Hill district of San Francisco on the western side of San Francisco Bay in the City of San Francisco between Mission Creek on the north and Islais Creek to the south. The approximately 500-acre area is more precisely described as a roughly rectangular district bounded by Sixteenth Street to the north, San Francisco Bay to the east, Islais Creek to the south, and U.S. Interstate 280 to the west. The area measures approximately 1.3 miles from north to south, and approximately 0.6 miles wide from east to west. (See Continuation Sheet, Pg. 2) *D4. Boundary Description (Describe limits of district and attach map showing boundary and district elements.): The Potrero Point (Central Waterfront) area is enclosed within a rectangle formed by the following streets and natural features: Beginning at the northwest corner of Pennsylvania and Sixteenth streets, the northern boundary of the area extends east along Sixteenth Street into San Francisco Bay. The boundary turns ninety degrees and heads south through the bay encompassing the entirety of Piers 70 and 80. At Islais Creek Channel, the boundary makes a ninety degree turn and heads west along the southern shore of the channel. -

R This Dissertation Has Been 63-4676 M Icrofilm Ed Exactly As Received

r This dissertation has been 63-4676 microfilmed exactly as received LORD, Georgianna Wuletich, 1931— THE ANNIHILATION OF ART IN THE POETRY OF WALLACE STEVENS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1962 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan significant value. All of its efforts, therefore, are to make the un real— that in which the imagination desires to believe— real and therefore worthy of belief. Stevens’ poetry and thought, then,springs from a dialectic between the imagination and reality, both of which are, in their most basic sense, internalized in the mind as wish (aspiration) and reason. Wish Implies the urge toward pleasure; reason, toward common sense and logic. Wish is the impulse toward grace; reason, toward gravity. Stevens believed that the dialectic between reality and the imagination is endless, that there is a war in the mind that will never end because the mind's desire to satisfy itself will never be fulfilled. Indeed, the major premise of Stevens' thought is that the wish of the imagination will never be ful filled. Underlying that major premise is a clash of irreconcilable desires: the desire to achieve fulfillment; the desire to be discon tent. Put another way, it is the desire to believe and the inability to (desire not to) believe. The imagination and reality enjoy a temporary armistice whenever each new wish postulated by the imagination is momentarily refined and sanctioned by reason, instead of being denied categorically. Ihat tem porary armistice is, as Stevens writes in "The Necessary Angel," a bal ance of imagination and reality (imagination and reason). -

India Basin Survey

INDIA BASIN SURVEY SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA FINAL REPORT REPORT PREPARED FOR BAYVIEW HISTORICAL SOCIETY May 1, 2008 KELLEY & VERPLANCK HISTORICAL RESOURCES CONSULTING 2912 DIAMOND STREET #330, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94131 415.337.5824 // WWW.KVPCONSULTING.COM Historic Context Statement India Basin Survey San Francisco, California TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 1 A. PURPOSE................................................................................................................................ 1 B. DEFINITION OF GEOGRAPHICAL AREA ................................................................................ 1 C. IDENTIFICATION OF HISTORIC CONTEXTS AND PERIODS OF SIGNIFICANCE .....................2 II. METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................. 3 III. IDENTIFICATION OF EXISTING HISTORIC STATUS............................................................... 4 A. HERE TODAY.........................................................................................................................4 B. 1976 CITYWIDE ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY ............................................................................4 C. SAN FRANCISCO ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE......................................................................4 D. ARTICLE 10 OF THE SAN FRANCISCO PLANNING CODE .......................................................5 -

Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey Summary Report and Draft Context Statement

Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey San Francisco Planning Department October 2000–September 2001, Page 1 Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey Summary Report and Draft Context Statement Figure 1: View from Jones and California Streets, looking toward Mission Bay, c. 1867. The activity which is the subject of this Cultural Resources Survey has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. October 2000 – October 2001 Prepared by: San Francisco Planning Department Acknowledging the contributions of: Central Waterfront Survey Advisory Committee San Francisco Architectural Heritage Dogpatch Neighborhood Association Page and Turnbull, Architects Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey San Francisco Planning Department October 2000–September 2001, Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Mayor Willie L. Brown, Jr. Planning Commission Anita Theoharis, President William Fay, Vice-President Roslyn Baltimore Hector Chinchilla Cynthia Joe Myrna Lim Jim Salinas, Sr. Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board Tim Kelley, President Suheil Shatara, Vice-President Ina Dearman Paul Finwall Nancy Ho-Belli -

D. Cultural Resources Archeological Resources

4. Environmental Setting and Impacts D. CULTURAL RESOURCES Section 4.D, Cultural Resources, considers both archeological resources, tribal cultural resources, and historic architectural resources. Archeological resources are discussed first, followed by a separate discussion of historic architectural resources that begins on p. 4.D.33. ARCHEOLOGICAL RESOURCES This subsection assesses the potential for the presence of archeological resources within the project site, provides a context for evaluating the significance of archeological resources that may be encountered, evaluates the potential impacts (project and cumulative) of the Proposed Project on archeological resources, and provides mitigation measures that would avoid or reduce potential impacts on archeological resources. An independent consultant has prepared an Archeological Research Design and Treatment Plan (ARDTP) for the project site.1 The research and recommendations of the ARDTP are the basis for the information and conclusions of this EIR section with respect to archeological resources. The information in the ARDTP used in the preparation of this subsection was obtained from regional databases, plans, and reports relevant to the Proposed Project, including the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park photographic collection; the San Francisco History Center at the San Francisco Public Library; Sanborn Fire Insurance maps;2 San Francisco newspapers; the California Digital Newspaper Collection, sponsored by the University of California, Riverside; the Online Archive of California; the Union Iron Works Historic District National Register Nomination Form; the Library of Congress; and the David Rumsey Map Collection, which also provided useful sources of online maps, including those from the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, U.S. Geological Survey, and official City and County survey maps. -

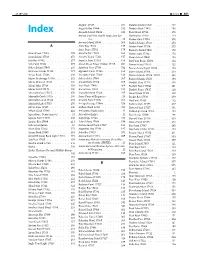

25 JUL 2021 Index Aaron Creek 17385 179 Aaron Island

26 SEP 2021 Index 401 Angoon 17339 �� � � � � � � � � � 287 Baranof Island 17320 � � � � � � � 307 Anguilla Bay 17404 �� � � � � � � � 212 Barbara Rock 17431 � � � � � � � 192 Index Anguilla Island 17404 �� � � � � � � 212 Bare Island 17316 � � � � � � � � 296 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Ser- Bar Harbor 17430 � � � � � � � � 134 vice � � � � � � � � � � � � 24 Barlow Cove 17316 �� � � � � � � � 272 Animas Island 17406 � � � � � � � 208 Barlow Islands 17316 �� � � � � � � 272 A Anita Bay 17382 � � � � � � � � � 179 Barlow Point 17316 � � � � � � � � 272 Anita Point 17382 � � � � � � � � 179 Barnacle Rock 17401 � � � � � � � 172 Aaron Creek 17385 �� � � � � � � � 179 Annette Bay 17428 � � � � � � � � 160 Barnes Lake 17382 �� � � � � � � � 172 Aaron Island 17316 �� � � � � � � � 273 Annette Island 17434 � � � � � � � 157 Baron Island 17420 �� � � � � � � � 122 Aats Bay 17402� � � � � � � � � � 277 Annette Point 17434 � � � � � � � 156 Bar Point Basin 17430� � � � � � � 134 Aats Point 17402 �� � � � � � � � � 277 Annex Creek Power Station 17315 �� � 263 Barren Island 17434 � � � � � � � 122 Abbess Island 17405 � � � � � � � 203 Appleton Cove 17338 � � � � � � � 332 Barren Island Light 17434 �� � � � � 122 Abraham Islands 17382 � � � � � � 171 Approach Point 17426 � � � � � � � 162 Barrie Island 17360 � � � � � � � � 230 Abrejo Rocks 17406 � � � � � � � � 208 Aranzazu Point 17420 � � � � � � � 122 Barrier Islands 17386, 17387 �� � � � 228 Adams Anchorage 17316 � � � � � � 272 Arboles Islet 17406 �� � � � � � � � 207 Barrier Islands 17433 -

Roads Lead to San Francisco: Black Californian Networks of Community and the Struggle for Equality, 1849-1877

All Roads Lead to San Francisco: Black Californian Networks of Community and the Struggle for Equality, 1849-1877 By Eunsun Celeste Han B. A., Seoul National University, 2009 M. A., Brown University, 2010 Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Eunsun Celeste Han This dissertation by Eunsun Celeste Han is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Michael Vorenberg, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Françoise Hamlin, Reader Date Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Date of Birth: April 11, 1986, Junjoo, Jeollabuk-do, South Korea EDUCATION Ph.D., History, May, 2015 Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island M.A., History, May, 2010 Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island B.A., Western History, Feb., 2009 summa cum laude, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea QUALIFYING FIELDS Nineteenth-Century U. S. History African American History Colonial Latin American History PUBLICATIONS Eunsun Celeste Han, “Making a Black Pacific: Black Californians and Transpacific Community Networks in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” under review at The Journal of African American History (2015). HONORS AND FELLOWSHIPS W. M. Keck Foundation Fellow at the Huntington, July-August, 2013 The Huntington Library, San Marino, California William G. McLoughlin Travel Fund, October, 2012 Brown University Department of History fund for research and conference travels William G.