DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Francisco, California

updated: 10.18.2017 Compressed Area - 4.5 Miles 2.5 Miles B C D E F G H J K L M N P Q R Fort Point Blue & Gold Blue & Gold San Francisco Bay Red & Fleet to Fleet to Vallejo, 1 Cable Car Route Golden Gate Bridge San Francisco, California USA White Fleet Angel Island Jack London Square 1 (toll south bound) San Francisco Bay Cruise Sausalito & & Oakland Street Car (F-Line) Maritime Tiburon & Bay Cruise Golden Gate National Recreation Area Alcatraz Ferry Service MasonCrissy St Field National PIER Historical Park 45 43 41 39 One Way Traffic 47 431/2 Pre Marina Green s Hyde St id l io Aquatic End of One Way Traffic l Pa rkwa Marina Blvd Pier d y e Park Blue & Gold v l Cervantes Blvd Direction of w Lin Jefferson St Ferry Pier 35 o B co MARINA Fort Mason The Highway Ramps Cruise Terminal D l The Walt n n Cannery Anchorage 2 l E 2 c m 33 Disney FISHERMANS Photo Vantage Points o B ba M c Family Palace Beach St Beach St r l c v n Museum Ghirardelli a & Scenic Views i WHARF d Baker d of Fine Arts L (Main Post) GGNRA Square e North Point St ro 31 BART Station Beach North Point St Headquarters t Shopping Area S Bay St Bay St Bay St Pier 27 a Alcatraz Departure Terminal Parks br James R. Herman m Cruise Terminal R Alha Moscone Francisco St Francisco St 3 Beaches Letterman i Lincoln Blvd c 3 h Rec Ctr THE Veterans Blvd Digital Arts a Chestnut St Points of Interest Center Aver Chestnut St TELEGRAPH EMBARCADERO ds “Crookedest HILL o Hospitals n d Lombard St Gen. -

H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space

IV. Environmental Setting and Impacts H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space Environmental Setting The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department maintains more than 200 parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the City. The City’s park system also includes 15 recreation centers, nine swimming pools, five golf courses as well as tennis courts, ball diamonds, athletic fields and basketball courts. The Recreation and Park Department manages the Marina Yacht Harbor, Candlestick (Monster) Park, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Lake Merced Complex. In total, the Department currently owns and manages roughly 3,380 acres of parkland and open space. Together with other city agencies and state and federal open space properties within the city, about 6,360 acres of recreational resources (a variety of parks, walkways, landscaped areas, recreational facilities, playing fields and unmaintained open areas) serve San Francisco.172 San Franciscans also benefit from the Bay Area regional open spaces system. Regional resources include public open spaces managed by the East Bay Regional Park District in Alameda and Contra Costa counties; the National Park Service in Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties as well as state park and recreation areas throughout. In addition, thousands of acres of watershed and agricultural lands are preserved as open spaces by water and utility districts or in private ownership. The Bay Trail is a planned recreational corridor that, when complete, will encircle San Francisco and San Pablo Bays with a continuous 400-mile network of bicycling and hiking trails. It will connect the shoreline of all nine Bay Area counties, link 47 cities, and cross the major toll bridges in the region. -

The Spreckels Mansion

THE SPRECKELS MANSION HISTORIC BEACH HOME At the time the house was built in the early 20th century, most of the homes being built in Coronado were Victorian-style architecture, constructed out of wood with an ornate design. At the time John D. Spreckels built his beach house, a mix of humble Italian Renaissance Revival and Beaux-Arts architectural styles, it stood in stark contrast to the neighboring homes. Today, it is one of the city’s few remaining examples possessing the distinctive characteristics of construction using reinforced concrete that has not been substantially altered. The 17,990 square-foot compound—nearly one-half acre, built on three contiguous 6,000 square-foot lots, includes a main house, a guest house and caretakers living quarters for a total of 12,750 square feet with a total of nine bedrooms, eight full bathrooms and three half bathrooms. The 6,600 square-foot main house originally featured six bedrooms, a Main House 1940’s basement and an attic has been modernized and restored to its turn of the century charm. A semi-circle drive fronted the home, while a central pergola was built atop the flat red-tiled roof as a third floor—an ideal setting to view the After recent restoration of the most historic home of Coronado, it retains Pacific Ocean. The smooth, cream-colored stucco façade completed the the most commanding vista on the island taking in America’s most Italian Renaissance look. The symmetrical appearance was further beautiful beach, the Coronado Islands, Point Loma, and romantic sunsets enhanced by chimneys at both ends of the home’s two adjoining wing. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson the Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER of EVERYTHING

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER OF EVERYTHING JACOB ADLER and ROBERT M. KAMINS Open Access edition funded by the National En- dowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non- commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copy- righted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824883669 (PDF) 9780824883676 (EPUB) This version created: 5 September, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1986 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Thelma C. Adler and Shirley R. Kamins In Phaethon’s Chariot … HAETHON, mortal child of the Sun God, was not believed by his Pcompanions when he boasted of his supernal origin. He en- treated Helios to acknowledge him by allowing him to drive the fiery chariot of the Sun across the sky. Against his better judg- ment, the father was persuaded. The boy proudly mounted the solar car, grasped the reins, and set the mighty horses leaping up into the eastern heavens. For a few ecstatic moments Phaethon was the Lord of the Sky. -

CRM Bulletin Vol. 12, No. 4 (1989)

Cfffl BULLETIN Volume 12: No. 4 Cultural Resources Management • National Park Service 1989 A Technical Bulletin for Parks, Federal Agencies, States, Local Governments, and the Private Sector Difficult Choices and Hard-Won Successes in Maritime Preservation reserving the remnants of America's life, times, and travails. Scores of wharves, and working waterfronts Pmaritime past poses special chal lighthouses, lifesaving stations, and that survived the decline of America lenges and problems. Ships were built other marine structures were built on as a seafaring nation often have not to last for a few decades, and then, if isolated shores, on surf-tossed survived waterfront redevelopment not on the bottom, were torn apart beaches, or on crumbling cliffs. Sub and urban renewal. with sledges, axes, or cutting torches jected to the powerful fury of ocean Ships, lighthouses, and other mari by shipbreakers. Sailors lived a hard waves, and the corrosive salt air of time relics are often saved by people life at sea and ashore; often illiterate, the marine environment, many suc they left little written record of their cumbed to the sea. Those buildings, (continued on page 2) Grim Realities, High Hopes, Moderate Gains: The State of Historic Ship Preservation James P. Delgado hile maritime preservation is maritime cultural resources were historic vessels slowly followed, in Wconcerned with all aspects of the originally created to serve or assist large part after the Depression, with Nation's seafaring past, including ships and shipping. the establishment of maritime lighthouses, shipyards, canals, and Historic ship preservation in the museums that included large ships— sail lofts, the major effort and atten United States dates to the last cen Mystic Seaport being the first major tion has been devoted to historic tury, when public interest and outcry example. -

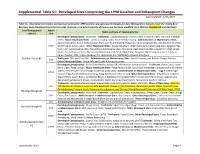

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015 Table S1. Developed sites (name and type) comprising the 1998 baseline and subsequent changes per Bear Management Subunit inside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone (Developed sites that are new, removed, or in which capacity of human-use has been modified since 1998 are highlighted and italicized). Bear Management Admin Name and type of developed sites subunit Unit Developed Campgrounds: Cave Falls. Trailheads: Coyote Meadows, Hominy Peak, S. Boone Creek, Fish Lake, Cascade Creek. Major Developed Sites: Loll Scout Camp, Idaho Youth Services Camp. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Squirrel Meadows Guard Station/Cabin, Porcupine Guard Station, Badger Creek Seismograph Site, and Squirrel Meadows CTNF GS/WY Game & Fish Cabin. Other Developed Sites: Grassy Lake Dam, Tillery Lake Dam, Indian Lake Dam, Bergman Res. Dam, Loon Lake Disperse sites, Horseshoe Lake Disperse sites, Porcupine Creek Disperse sites, Gravel Pit/Target Range, Boone Creek Disperse Sites, Tillery Lake O&G Camp, Calf Creek O&G Camp, Bergman O&G Camp, Granite Creek Cow Camp, Poacher’s TH, Indian Meadows TH, McRenolds Res. TH/Wildlife Viewing Area/Dam. Bechler/Teton #1 Trailheads: 9K1 and Cave Falls. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: South Entrance and Bechler Ranger Stations. YNP Other Developed Sites: Union Falls and Snake River picnic areas. Developed Campgrounds: Grassy Lake Road campsites (8 individual car camping sites). Trailheads: Glade Creek, Lower Berry Creek, Flagg Canyon. Major Developed Sites: Flagg Ranch (lodge, cabins and Headwater Campground with camper cabins, remote cistern and sewage treatment plant sites). Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Flagg Ranch Ranger GTNP Station, Flagg Ranch employee housing, Flagg Ranch maintenance yard. -

Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

SDMS DOCID# 1137835 BAY FILL IN SAN FRANCISCO: A HISTORY OF CHANGE A thesis submitted to the faculty of California State University, San Francisco in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Gerald Robert Dow Department of Geography July 1973 Permission is granted for the material in this thesis to be reproduced in part or whole for the purpose of education and/or research. It may not be edited, altered, or otherwise modified, except with the express permission of the author. - ii - - ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Maps . vi INTRODUCTION . .1 CHAPTER I: JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES OF SAN FRANCISCO’S TIDELANDS . .4 Definition of Tidelands . .5 Evolution of Tideland Ownership . .5 Federal Land . .5 State Land . .6 City Land . .6 Sale of State Owned Tidelands . .9 Tideland Grants to Railroads . 12 Settlement of Water Lot Claims . 13 San Francisco Loses Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 14 San Francisco Regains Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 15 The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Port of San Francisco . 18 CHAPTER II: YERBA BUENA COVE . 22 Introduction . 22 Yerba Buena, the Beginning of San Francisco . 22 Yerba Buena Cove in 1846 . 26 San Francisco’s First Waterfront . 26 Filling of Yerba Buena Cove Begins . 29 The Board of State Harbor Commissioners and the First Seawall . 33 The New Seawall . 37 The Northward Expansion of San Francisco’s Waterfront . 40 North Beach . 41 Fisherman’s Wharf . 43 Aquatic Park . 45 - iii - Pier 45 . 47 Fort Mason . 48 South Beach . 49 The Southward Extension of the Great Seawall . -

Appendix 3-‐1 Historic Resources Evaluation

Appendix 3-1 Historic Resources Evaluation HISTORIC RESOURCE EVALUATION SEAWALL LOT 337 & Pier 48 Mixed-Use Development Project San Francisco, California April 11, 2016 Prepared by San Francisco, California Historic Resource Evaluation Seawall Lot 337 & Pier 48 Mixed-Use Project, San Francisco, CA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Methods ................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Regulatory Framework ....................................................................................................... 3 IV. Property Description ................................................................................................... ….....6 V. Historical Context ....................................................................................................... ….....24 VI. Determination of Eligibility.................................................................................... ……....44 VII. Evaluation of the Project for Compliance with the Standards ............................. 45 VIII. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 58 IX. Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ 59 April 11, 2016 Historic Resource Evaluation Seawall -

Map Showing Locations of Damaging Landslides in San Francisco City and County, California, Resulting from 1997-98 El Nino˜ Rainstorms

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MISCELLANEOUS FIELD STUDIES U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP MF-2325-G Pamphlet accompanies map SUMMARY Landslides in the city and county of San Francisco caused an estimated $4.1 million, including three red-tagged homes, extensive damage to the Olympic golf course, and minor damage to several residential properties. "Tagged" structures are those that have been either condemned (red) or in need of significant repair (yellow). Municipal and county building inspection departments EXPLANATION are commonly responsible for such determinations. According to a report from the Location of damaging landslide. The number San Francisco Chief Building Inspector, the damage mostly occurred on steep 2 slopes near Mount Sutro, Twin Peaks, Mount Davidson, Diamond Heights, identifies the landslide in the database. Data on Potrero Hill, and the Seacliff area. Most of the damage was reported between file with authors, USGS, Menlo Park, California February 2 and February 26, 1998, although a few slides occurred in January, the and Golden, Colorado. earliest being reported January 8. A reconnaissance survey was conducted on May 1, 1998, with brief visits to all but a few of the affected areas. Sources of information included a San Francisco Department of Building Inspection memorandum, dated 2/27/98, and various news reports. No reports assessing road damage in the county were obtained. A large rotational slump damaged three adjacent homes on the cliff above Phelan Beach in the Seacliff district. At the time of the survey, the houses were 4 closed to occupants and one house foundation was being stabilized. The slump reportedly began on February 8 after a week of heavy rain. -

October 2014

Brent ACTCM Bushnell & Get a Job at San Quentin INSIDE Sofa Carmi p. 23 p. 7 p. 3 p. 15 p. 17 p. 20 p. 25 OCTOBER 2014 Serving the Potrero Hill, Dogpatch, Mission Bay and SOMA Neighborhoods Since 1970 FREE Jackson Playground to Receive $1.6 Million, Mostly to Plan Clubhouse Upgrades BY KEITH BURBANK The Eastern Neighborhood Citi- zen’s Advisory Committee (ENCAC) has proposed that San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department invest $1.6 million in developer fees over the next four years to improve Jackson Playground. One million dollars would be directed towards developing designs to renovate the playground’s clubhouse, which Rec and Park estimates will cost $13.5 million to fully execute, with a higher price tag if the building is expanded. The Scents of Potrero Hill ENCAC’s recommendations will be transmitted to the San Francisco BY RYAN BERGMANN Above, First Spice Company blends many spices Board of Supervisors, where they’re in its Potrero location, which add to the fragrance expected to be adopted. According Potrero Hill has a cacophony of in the air, including, red pepper, turmeric, bay to the Committee’s bylaws, ENCAC smells, emanating from backyard leaves, curry powder, coriander, paprika, sumac, collaborates “with the Planning De- gardens, street trees, passing cars, monterey chili, all spice, and rosemary. Below, partment and the Interagency Plan and neighborhood restaurants and Anchor Steam at 17th and Mariposa, emits Implementation Committee on pri- the aroma of barley malt cooking in hot water. bakeries. But two prominent scents oritizing…community improvement PHOTOGRAPHS BY GABRIELLE LURIE tend to linger year-round, no mat- projects and identifying implemen- ter which way the wind is blowing, tation details as part of an annual evolving throughout the day. -

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 MARITIME HERITAGE OF THE UNITED STATES NHL THEME STUDY LARGE VESSELS FERRY BERKELEY Page 1 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Berkeley Other Name/Site Number: Ferry Berkeley 2. LOCATION Street & Number: B Street Pier Not for publication: City/Town: San Diego Vicinity: State: CA County: San Diego Code: 073 Zip Code: 92101 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s):_ Public-local: District:_ Public-State: __ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: X Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ____ buildings ____ sites ____ structures ____ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: NFS FORM 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 FERRY BERKELEY Page 2 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria.