Philosophy of Physical Activity Education (Including Educational Sport)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.5 Rules for Evaluating Syllogisms

6.5 Rules for Evaluating Syllogisms Comment: Venn Diagrams provide a clear semantics for categorical statements that yields a method for determining validity. Prior to their discovery, categorical syllogisms were evaluated by a set of rules, some of which are more or less semantic in character, others of which are entirely syntactic. We will study those rules in this section. Rule 1: A valid standard form categorical syllogism must contain exactly three terms, and each term must be used with the same meaning throughout the argument. Comment: A fallacy of equivocation occurs if a term is used with more than one meaning in a categorical syllogism, e.g., Some good speakers are woofers. All politicians are good speakers. So, some politicians are woofers. In the first premise, “speakers” refers to an electronic device. In the second, it refers to a subclass of human beings. Definition (sorta): A term is distributed in a statement if the statement “says something” about every member of the class that the term denotes. A term is undistributed in a statement if it is not distributed in it. Comment: To say that a statement “says something” about every member of a class is to say that, if you know the statement is true, you can legitimately infer something nontrivial about any arbitrary member of the class. 1 The subject term (but not the predicate term) is distributed in an A statement. Example 1 All dogs are mammals says of each dog that it is a mammal. It does not say anything about all mammals. Comment: Thus, if I know that “All dogs are mammals” is true, then if I am told that Fido is a dog, I can legitimately infer that Fido is a mammal. -

Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies

9/17/2021 Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies- Examrace Examrace Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for competitive exams : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of your exam. Western Logic - Formal & Informal Fallacy: Types of 6 Fallacies (Philosophy) Fallacy When an argument fails to support its conclusion, that argument is termed as fallacious in nature. A fallacious argument is hence an erroneous argument. In other words, any error or mistake in an argument leads to a fallacy. So, the definition of fallacy is any argument which although seems correct but has an error committed in its reasoning. Hence, a fallacy is an error; a fallacious argument is an argument which has erroneous reasoning. In the words of Frege, the analytical philosopher, “it is a logician՚s task to identify the pitfalls in language.” Hence, logicians are concerned with the task of identifying fallacious arguments in logic which are also called as incorrect or invalid arguments. There are numerous fallacies but they are classified under two main heads; Formal Fallacies Informal Fallacies Formal Fallacies Formal fallacies are those mistakes or errors which occur in the form of the argument. In other words, formal fallacies concern themselves with the form or the structure of the argument. Formal fallacies are present when there is a structural error in a deductive argument. It is important to note that formal fallacies always occur in a deductive argument. There are of six types; Fallacy of four terms: A valid syllogism must contain three terms, each of which should be used in the same sense throughout; else it is a fallacy of four terms. -

Indiscernible Logic: Using the Logical Fallacies of the Illicit Major Term and the Illicit Minor Term As Litigation Tools

WLR_47-1_RICE (FINAL FORMAT) 10/28/2010 3:35:39 PM INDISCERNIBLE LOGIC: USING THE LOGICAL FALLACIES OF THE ILLICIT MAJOR TERM AND THE ILLICIT MINOR TERM AS LITIGATION TOOLS ∗ STEPHEN M. RICE I. INTRODUCTION Baseball, like litigation, is at once elegant in its simplicity and infinite in its complexities and variations. As a result of its complexities, baseball, like litigation, is subject to an infinite number of potential outcomes. Both baseball and litigation are complex systems, managed by specialized sets of rules. However, the results of baseball games, like the results of litigation, turn on a series of indiscernible, seemingly invisible, rules. These indiscernible rules are essential to success in baseball, in the same way the rules of philosophic logic are essential to success in litigation. This article will evaluate one of the philosophical rules of logic;1 demonstrate how it is easily violated without notice, resulting in a logical fallacy known as the Fallacy of the Illicit Major or Minor Term,2 chronicle how courts have identified this logical fallacy and used it to evaluate legal arguments;3 and describe how essential this rule and the fallacy that follows its breach is to essential effective advocacy. However, because many lawyers are unfamiliar with philosophical logic, or why it is important, this article begins with a story about a familiar subject that is, in many ways, like the rules of philosophic logic: the game of baseball. ∗ Stephen M. Rice is an Assistant Professor of Law, Liberty University School of Law. I appreciate the efforts of my research assistant, Ms. -

Tel Aviv University the Lester & Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities the Shirley & Leslie Porter School of Cultural Studies

Tel Aviv University The Lester & Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities The Shirley & Leslie Porter School of Cultural Studies "Mischief … none knows … but herself": Intrigue and its Relation to the Drive in Late Seventeenth-Century Intrigue Drama Thesis Submitted for the Degree of "Doctor of Philosophy" by Zafra Dan Submitted to the Senate of Tel Aviv University October 2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Shirley Sharon-Zisser, Tel Aviv University and Professor Karen Alkalay-Gut, Tel Aviv University This thesis, this labor of love, would not have come into the world without the rigorous guidance, the faith and encouragement of my supervisors, Prof. Karen Alkalay-Gut and Prof. Shirley Sharon-Zisser. I am grateful to Prof. Sharon-Zisser for her Virgilian guidance into and through the less known, never to be taken for granted, labyrinths of Freudian and Lacanian thought and theory, as well as for her own ground-breaking contribution to the field of psychoanalysis through psycho-rhetoric. I am grateful to Prof. Alkalay-Gut for her insightful, inspiring yet challenging comments and questions, time and again forcing me to pause and rethink the relationship between the literary aspects of my research and psychoanalysis. I am grateful to both my supervisors for enabling me to explore a unique, newly blazed path to literary form, and rediscover thus late seventeenth-century drama. I wish to express my gratitude to Prof. Ruth Ronen for allowing me the use of the manuscript of her book Aesthetics of Anxiety before it was published. Her instructive work has been a source of enlightenment and inspiration in its own right. -

Leading Logical Fallacies in Legal Argument – Part 1 Gerald Lebovits

University of Ottawa Faculty of Law (Civil Law Section) From the SelectedWorks of Hon. Gerald Lebovits July, 2016 Say It Ain’t So: Leading Logical Fallacies in Legal Argument – Part 1 Gerald Lebovits Available at: https://works.bepress.com/gerald_lebovits/297/ JULY/AUGUST 2016 VOL. 88 | NO. 6 JournalNEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Highlights from Today’s Game: Also in this Issue Exclusive Use and Domestic Trademark Coverage on the Offensive Violence Health Care Proxies By Christopher Psihoules and Jennette Wiser Litigation Strategy and Dispute Resolution What’s in a Name? That Which We Call Surrogate’s Court UBE-Shopping and Portability THE LEGAL WRITER BY GERALD LEBOVITS Say It Ain’t So: Leading Logical Fallacies in Legal Argument – Part 1 o argue effectively, whether oral- fact.3 Then a final conclusion is drawn able doubt. The jury has reasonable ly or in writing, lawyers must applying the asserted fact to the gen- doubt. Therefore, the jury hesitated.”8 Tunderstand logic and how logic eral rule.4 For the syllogism to be valid, The fallacy: Just because the jury had can be manipulated through fallacious the premises must be true, and the a reasonable doubt, the jury must’ve reasoning. A logical fallacy is an inval- conclusion must follow logically. For hesitated. The jury could’ve been id way to reason. Understanding falla- example: “All men are mortal. Bob is a entirely convinced and reached a con- cies will “furnish us with a means by man. Therefore, Bob is mortal.” clusion without hesitation. which the logic of practical argumen- Arguments might not be valid, tation can be tested.”1 Testing your though, even if their premises and con- argument against the general types of clusions are true. -

Formal Fallacies

First Steps in Formal Logic Handout 16 Formal Fallacies A formal fallacy is an invalid argument grounded in logical form. Validity, again: an argument is valid iff the premises could not all be true yet the conclusion false; or, a rule of inference is valid iff it cannot lead from truth to falsehood, i.e. if the infer- ence preserves truth. The semantic turnstile ‘⊧’ indicates validity, so where P is the set of premises and C is the conclusion, P ⊧ C. We can also say that C is a ‘logical consequence’ of, or follows from, P. In a fallacious argument, this may seem to be the case, but P ⊭ C. There are also many informal fallacies (e.g., begging the question: petitio principii) that do not preserve truth either, but these are not grounded in logical form. Fallacies of Propositional Logic (PL) (1) Affirming the Consequent: φ ⊃ ψ, ψ ⊦ φ Examples: (a) ‘If Hume is an atheist, then Spinoza is an atheist too. Spinoza is an atheist. So, Hume is an atheist.’ (b) ‘If it rains, the street is wet. The street is wet. So it rains.’ (2) Denying the Antecedent: φ ⊃ ψ, ~φ ⊦ ~ψ Examples: (a) ‘If Locke is a rationalist, then Spinoza grinds lenses for a living. But Locke is not a rationalist. So, Spinoza does not grind lenses for a living.’ (b) ‘If it rains, the street it wet. It does not rain. So the street is not wet.’ Affirming the consequent and denying the antecedent are quite common fallacies. They ignore that the material implication lacks an intrinsic connection between antecedent and consequent. -

Logic Made Easy: How to Know When Language Deceives

LOGIC MADE EASY ALSO BY DEBORAH J. BENNETT Randomness LOGIC MADE EASY How to Know When Language Deceives You DEBORAH J.BENNETT W • W • NORTON & COMPANY I ^ I NEW YORK LONDON Copyright © 2004 by Deborah J. Bennett All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, WW Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 Manufacturing by The Haddon Craftsmen, Inc. Book design by Margaret M.Wagner Production manager: Julia Druskin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bennett, Deborah J., 1950- Logic made easy : how to know when language deceives you / Deborah J. Bennett.— 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-393-05748-8 1. Reasoning. 2. Language and logic. I.Title. BC177 .B42 2004 160—dc22 2003026910 WW Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www. wwnor ton. com WW Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76Wells Street, LondonWlT 3QT 1234567890 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: LOGIC IS RARE I 1 The mistakes we make l 3 Logic should be everywhere 1 8 How history can help 19 1 PROOF 29 Consistency is all I ask 29 Proof by contradiction 33 Disproof 3 6 I ALL 40 All S are P 42 Vice Versa 42 Familiarity—help or hindrance? 41 Clarity or brevity? 50 7 8 CONTENTS 3 A NOT TANGLES EVERYTHING UP 53 The trouble with not 54 Scope of the negative 5 8 A and E propositions s 9 When no means yes—the "negative pregnant" and double negative 61 k SOME Is PART OR ALL OF ALL 64 Some -

Categorical Syllogism

Unit 8 Categorical Syllogism What is a syllogism? Inference or reasoning is the process of passing from one or more propositions to another with some justification. This inference when expressed in language is called an argument. An argument consists of more than one proposition (premise and conclusion). The conclusion of an argument is the proposition that is affirmed on the basis of the other propositions of the argument. These other propositions which provide support or ground for the conclusion are called premises of the argument. Inferences have been broadly divided as deductive and inductive. A deductive argument makes the claim that its conclusion is supported by its premises conclusively. An inductive argument, in contrast, does not make such a claim. It claims to support its conclusion only with some degrees of probability. Deductive inferences are again divided into Immediate and Mediate. Immediate inference is a kind of deductive inference in which the conclusion follows from one premise only. In mediate inference, on the other hand, the conclusion follows from more them one premise. Where there are only two premises, and the conclusion follows from them jointly, it is called syllogism. A syllogism is a deductive argument in which a conclusion is inferred from two premises. The syllogisms with which we are concerned here are called categorical because they are arguments based on the categorical relations of classes or categories. Such relations are of three kinds. 1. The whole of one class may be included in the other class such as All dogs are mammals. 2. Some members of one class may be included in the other such as Some chess players are females. -

Volume 39 Number 3 2014

Volume 39 Number 3 2014 © 2014 Brooklyn Journal of International Law BROOKLYN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW (ISSN 0740-4824) The Brooklyn Journal of International Law is published three times a year by Brooklyn Law School, 250 Joralemon Street, Brooklyn, New York 11201. You may contact the Journal by phone at (718) 780-7971, by fax at (718) 780-0353, or by email at [email protected]. Please visit the Journal at Brooklyn Law School’s website, www.brooklaw.edu/bjil. Subscriptions: Subscriptions are $25 ($28 foreign) per year and cover all issues in one volume. All institutional subscriptions are now handled through subscription consolidators, such as Hein, EBSCO, or others. If you have questions about an individual subscription placed originally through the Law School, or any other subscription issues, please email jour- [email protected] or write to the Journal Coordinator, Brook- lyn Law School, 250 Joralemon Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. Please be sure to specify the name of the Journal you are inquiring about. Single and Back Issues: Single and back issues may be ordered directly through William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14209- 1987, Tel: 800/828-7571. Back issues can also be found in electronic format on HeinOnline at http://www.heinonline.org, (available to HeinOnline sub- scribers). Manuscripts: The Brooklyn Journal of International Law will consider un- solicited manuscripts for publication. Manuscripts must be typed, double- spaced, and in Microsoft Word format, with footnotes rather than endnotes. Manuscripts may be emailed to [email protected] or sent in duplicate hard copy format to the Editor-in-Chief, Brooklyn Journal of International Law, 250 Joralemon Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. -

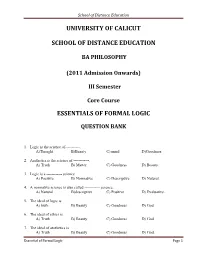

Essentials of Formal Logic-III Sem Core Course

School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION BA PHILOSOPHY (2011 Admission Onwards) III Semester Core Course ESSENTIALS OF FORMAL LOGIC QUESTION BANK 1. Logic is the science of-----------. A)Thought B)Beauty C) mind D)Goodness 2. Aesthetics is the science of ------------. A) Truth B) Matter C) Goodness D) Beauty. 3. Logic is a ------------ science A) Positive B) Normative C) Descriptive D) Natural. 4. A normative science is also called ------------ science. A) Natural B)descriptive C) Positive D) Evaluative. 5. The ideal of logic is A) truth B) Beauty C) Goodness D) God 6. The ideal of ethics is A) Truth B) Beauty C) Goodness D) God 7. The ideal of aesthetics is A) Truth B) Beauty C) Goodness D) God. Essential of Formal Logic Page 1 School of Distance Education 8. The process by which one proposition is arrived at on the basis of other propositions is called-----------. A) Term B) Concept C) Inference D) Connotation. 9. Only--------------- sentences can become propositions. A) Indicative B) Exclamatory C) Interogative D) Imperative. 10. Propositions which supports the conclusion of an argument are called A) Inferences B) Premises C) Terms D) Concepts. 11. That proposition which is affirmed on the basis of premises is called A) Term B) Concept C) Idea D) Conclusion. 12. The etymological meaning of the word logic is A) the science of mind B) the science of thought C) the science of conduct D) the science of beautyody . 13. The systematic body of knowledge about a particular branch of the universe is called------- . A) Science B) Art C) Religion D) Opinion. -

Stephen M. Rice, Leveraging Logical Form in Legal Argument

OCULREV Winter 2015 551-96 Rice 3-14 (Do Not Delete) 3/14/2016 7:38 PM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 40 WINTER 2015 NUMBER 3 ARTICLE LEVERAGING LOGICAL FORM IN LEGAL ARGUMENT: THE INHERENT AMBIGUITY IN LOGICAL DISJUNCTION AND ITS IMPLICATION IN LEGAL ARGUMENT Stephen M. Rice* I. INTRODUCTION: LOGIC’S QUIET, PERVASIVE ROLE IN ADVOCACY Trial lawyers love to design carefully constructed arguments. However, they do not always consider some of the most important details of persuasive advocacy—the logical structure of their arguments.1 While lawyers are well aware of their obligations to master and marshal the law and the facts in support of a client’s claim, they are generally not so intentional about mastering and marshaling the internal logic of the pleadings they design, briefs they write, or contracts and statutes they read or draft. In fact, many lawyers are surprised to learn that—in addition to the rules of law—there are rules of logic that ensure and test the integrity of legal argument.2 It is important to note that these rules of * Professor of Law, Liberty University School of Law. 1. See Gary L. Sasso, Appellate Oral Argument, LITIG., Summer 1994, at 27, 27, 31 (illustrating the importance of a carefully constructed argument). 2. See generally Stephen M. Rice, Conspicuous Logic: Using the Logical Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent as a Litigation Tool, 14 BARRY L. REV. 1 (2010) [hereinafter Rice, Conspicuous Logic]; Stephen M. Rice, Conventional Logic: Using the Logical 551 OCULREV Winter 2015 551-96 Rice 3-14 (Do Not Delete) 3/14/2016 7:38 PM 552 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. -

Denying the Antecedent - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Denying the antecedent - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Help us provide free content to the world by • LearnLog more in /about create using Wikipediaaccount for research donating today ! • Article Discussion EditDenying this page History the antecedent From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Denying the antecedent is a formal fallacy, committed by reasoning in the form: If P , then Q . Navigation Not P . ● Main Page Therefore, not Q . ● Contents Arguments of this form are invalid (except in the rare cases where such an argument also ● Featured content instantiates some other, valid, form). Informally, this means that arguments of this form do ● Current events ● Random article not give good reason to establish their conclusions, even if their premises are true. Interaction The name denying the ● About Wikipedia antecedent derives from the premise "not P ", which denies the 9, 2008 ● Community portal "if" clause of the conditional premise.Lehman, v. on June ● Recent changes Carver One way into demonstrate archivedthe invalidity of this argument form is with a counterexample with ● Contact Wikipedia Cited true premises06-35176 but an obviously false conclusion. For example: ● Donate to No. If Queen Elizabeth is an American citizen, then she is a human being. Wikipedia ● Help Queen Elizabeth is not an American citizen. Therefore, Queen Elizabeth is not a human being. Search That argument is obviously bad, but arguments of the same form can sometimes seem superficially convincing, as in the following example imagined by Alan Turing in the article "Computing Machinery and Intelligence": “ If each man had a definite set of rules of conduct by which he regulated his life he would be no better than a machine.