CATEGORICAL INFERENCES Inference Is the Process by Which

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.5 Rules for Evaluating Syllogisms

6.5 Rules for Evaluating Syllogisms Comment: Venn Diagrams provide a clear semantics for categorical statements that yields a method for determining validity. Prior to their discovery, categorical syllogisms were evaluated by a set of rules, some of which are more or less semantic in character, others of which are entirely syntactic. We will study those rules in this section. Rule 1: A valid standard form categorical syllogism must contain exactly three terms, and each term must be used with the same meaning throughout the argument. Comment: A fallacy of equivocation occurs if a term is used with more than one meaning in a categorical syllogism, e.g., Some good speakers are woofers. All politicians are good speakers. So, some politicians are woofers. In the first premise, “speakers” refers to an electronic device. In the second, it refers to a subclass of human beings. Definition (sorta): A term is distributed in a statement if the statement “says something” about every member of the class that the term denotes. A term is undistributed in a statement if it is not distributed in it. Comment: To say that a statement “says something” about every member of a class is to say that, if you know the statement is true, you can legitimately infer something nontrivial about any arbitrary member of the class. 1 The subject term (but not the predicate term) is distributed in an A statement. Example 1 All dogs are mammals says of each dog that it is a mammal. It does not say anything about all mammals. Comment: Thus, if I know that “All dogs are mammals” is true, then if I am told that Fido is a dog, I can legitimately infer that Fido is a mammal. -

Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies

9/17/2021 Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies- Examrace Examrace Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for competitive exams : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of your exam. Western Logic - Formal & Informal Fallacy: Types of 6 Fallacies (Philosophy) Fallacy When an argument fails to support its conclusion, that argument is termed as fallacious in nature. A fallacious argument is hence an erroneous argument. In other words, any error or mistake in an argument leads to a fallacy. So, the definition of fallacy is any argument which although seems correct but has an error committed in its reasoning. Hence, a fallacy is an error; a fallacious argument is an argument which has erroneous reasoning. In the words of Frege, the analytical philosopher, “it is a logician՚s task to identify the pitfalls in language.” Hence, logicians are concerned with the task of identifying fallacious arguments in logic which are also called as incorrect or invalid arguments. There are numerous fallacies but they are classified under two main heads; Formal Fallacies Informal Fallacies Formal Fallacies Formal fallacies are those mistakes or errors which occur in the form of the argument. In other words, formal fallacies concern themselves with the form or the structure of the argument. Formal fallacies are present when there is a structural error in a deductive argument. It is important to note that formal fallacies always occur in a deductive argument. There are of six types; Fallacy of four terms: A valid syllogism must contain three terms, each of which should be used in the same sense throughout; else it is a fallacy of four terms. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Reliability of Mathematical Inference

Reliability of mathematical inference Jeremy Avigad Department of Philosophy and Department of Mathematical Sciences Carnegie Mellon University January 2020 Formal logic and mathematical proof An important mathematical goal is to get the answers right: • Our calculations are supposed to be correct. • Our proofs are supposed to be correct. Mathematical logic offers an idealized account of correctness, namely, formal derivability. Informal proof is viewed as an approximation to the ideal. • A mathematician can be called on to expand definitions and inferences. • The process has to terminate with fundamental notions, assumptions, and inferences. Formal logic and mathematical proof Two objections: • Few mathematicians can state formal axioms. • There are various formal foundations on offer. Slight elaboration: • Ordinary mathematics relies on an informal foundation: numbers, tuples, sets, functions, relations, structures, . • Formal logic accounts for those (and any of a number of systems suffice). Formal logic and mathematical proof What about intuitionstic logic, or large cardinal axioms? Most mathematics today is classical, and does not require strong assumptions. But even in those cases, the assumptions can be make explicit and formal. Formal logic and mathematical proof So formal derivability provides a standard of correctness. Azzouni writes: The first point to observe is that formalized proofs have become the norms of mathematical practice. And that is to say: should it become clear that the implications (of assumptions to conclusion) of an informal proof cannot be replicated by a formal analogue, the status of that informal proof as a successful proof will be rejected. Formal verification, a branch of computer science, provides corroboration: computational proof assistants make formalization routine (though still tedious). -

Misconceived Relationships Between Logical Positivism and Quantitative Research: an Analysis in the Framework of Ian Hacking

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 452 266 TM 032 553 AUTHOR Yu, Chong Ho TITLE Misconceived Relationships between Logical Positivism and Quantitative Research: An Analysis in the Framework of Ian Hacking. PUB DATE 2001-04-07 NOTE 26p. PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) ED 2S PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. 'DESCRIPTORS *Educational Research; *Research Methodology IDENTIFIERS *Logical Positivism ABSTRACT Although quantitative research methodology is widely applied by psychological researchers, there is a common misconception that quantitative research is based on logical positivism. This paper examines the relationship between quantitative research and eight major notions of logical positivism:(1) verification;(2) pro-observation;(3) anti-cause; (4) downplaying explanation;(5) anti-theoretical entities;(6) anti-metaphysics; (7) logical analysis; and (8) frequentist probability. It is argued that the underlying philosophy of modern quantitative research in psychology is in sharp contrast to logical positivism. Putting the labor of an out-dated philosophy into quantitative research may discourage psychological researchers from applying this research approach and may also lead to misguided dispute between quantitative and qualitative researchers. What is needed is to encourage researchers and students to keep an open mind to different methodologies and apply skepticism to examine the philosophical assumptions instead of accepting them unquestioningly. (Contains 1 figure and 75 references.)(Author/SLD) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Misconceived relationships between logical positivism and quantitative research: An analysis in the framework of Ian Hacking Chong Ho Yu, Ph.D. Arizona State University April 7, 2001 N N In 4-1 PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIALHAS BEEN GRANTED BY Correspondence: TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Chong Ho Yu, Ph.D. -

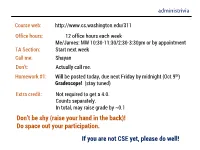

CSE Yet, Please Do Well! Logical Connectives

administrivia Course web: http://www.cs.washington.edu/311 Office hours: 12 office hours each week Me/James: MW 10:30-11:30/2:30-3:30pm or by appointment TA Section: Start next week Call me: Shayan Don’t: Actually call me. Homework #1: Will be posted today, due next Friday by midnight (Oct 9th) Gradescope! (stay tuned) Extra credit: Not required to get a 4.0. Counts separately. In total, may raise grade by ~0.1 Don’t be shy (raise your hand in the back)! Do space out your participation. If you are not CSE yet, please do well! logical connectives p q p q p p T T T T F T F F F T F T F NOT F F F AND p q p q p q p q T T T T T F T F T T F T F T T F T T F F F F F F OR XOR 푝 → 푞 • “If p, then q” is a promise: p q p q F F T • Whenever p is true, then q is true F T T • Ask “has the promise been broken” T F F T T T If it’s raining, then I have my umbrella. related implications • Implication: p q • Converse: q p • Contrapositive: q p • Inverse: p q How do these relate to each other? How to see this? 푝 ↔ 푞 • p iff q • p is equivalent to q • p implies q and q implies p p q p q Let’s think about fruits A fruit is an apple only if it is either red or green and a fruit is not red and green. -

Conditional Statement/Implication Converse and Contrapositive

Conditional Statement/Implication CSCI 1900 Discrete Structures •"ifp then q" • Denoted p ⇒ q – p is called the antecedent or hypothesis Conditional Statements – q is called the consequent or conclusion Reading: Kolman, Section 2.2 • Example: – p: I am hungry q: I will eat – p: It is snowing q: 3+5 = 8 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 1 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 2 Conditional Statement/Implication Truth Table Representing Implication (continued) • In English, we would assume a cause- • If viewed as a logic operation, p ⇒ q can only be and-effect relationship, i.e., the fact that p evaluated as false if p is true and q is false is true would force q to be true. • This does not say that p causes q • If “it is snowing,” then “3+5=8” is • Truth table meaningless in this regard since p has no p q p ⇒ q effect at all on q T T T • At this point it may be easiest to view the T F F operator “⇒” as a logic operationsimilar to F T T AND or OR (conjunction or disjunction). F F T CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 3 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 4 Examples where p ⇒ q is viewed Converse and contrapositive as a logic operation •Ifp is false, then any q supports p ⇒ q is • The converse of p ⇒ q is the implication true. that q ⇒ p – False ⇒ True = True • The contrapositive of p ⇒ q is the –False⇒ False = True implication that ~q ⇒ ~p • If “2+2=5” then “I am the king of England” is true CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 5 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 6 1 Converse and Contrapositive Equivalence or biconditional Example Example: What is the converse and •Ifp and q are statements, the compound contrapositive of p: "it is raining" and q: I statement p if and only if q is called an get wet? equivalence or biconditional – Implication: If it is raining, then I get wet. -

Section 2.1: Proof Techniques

Section 2.1: Proof Techniques January 25, 2021 Abstract Sometimes we see patterns in nature and wonder if they hold in general: in such situations we are demonstrating the appli- cation of inductive reasoning to propose a conjecture, which may become a theorem which we attempt to prove via deduc- tive reasoning. From our work in Chapter 1, we conceive of a theorem as an argument of the form P → Q, whose validity we seek to demonstrate. Example: A student was doing a proof and suddenly specu- lated “Couldn’t we just say (A → (B → C)) ∧ B → (A → C)?” Can she? It’s a theorem – either we prove it, or we provide a counterexample. This section outlines a variety of proof techniques, including direct proofs, proofs by contraposition, proofs by contradiction, proofs by exhaustion, and proofs by dumb luck or genius! You have already seen each of these in Chapter 1 (with the exception of “dumb luck or genius”, perhaps). 1 Theorems and Informal Proofs The theorem-forming process is one in which we • make observations about nature, about a system under study, etc.; • discover patterns which appear to hold in general; • state the rule; and then • attempt to prove it (or disprove it). This process is formalized in the following definitions: • inductive reasoning - drawing a conclusion based on experi- ence, which one might state as a conjecture or theorem; but al- mostalwaysas If(hypotheses)then(conclusion). • deductive reasoning - application of a logic system to investi- gate a proposed conclusion based on hypotheses (hence proving, disproving, or, failing either, holding in limbo the conclusion). -

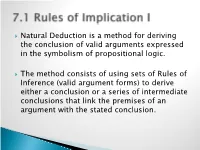

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Philosophy of Physical Activity Education (Including Educational Sport)

eBook Philosophy of Physical Activity Education (Including Educational Sport) by EARLEPh.D., F. LL.D., ZEIGLER D.Sc. PHILOSOPHY OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY EDUCATION (INCLUDING EDUCATIONAL SPORT) Earle F. Zeigler Ph.D., LL.D., D.Sc., FAAKPE Faculty of Kinesiology The University of Western Ontario London, Canada (This version is as an e-book) 1 PLEASE LEAVE THIS PAGE EMPTY FOR PUBLICATION DATA 2 DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the following men and women with whom I worked very closely in this aspect of our work at one time or another from 1956 on while employed at The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; the University of Illinois, U-C; and The University of Western Ontario, London, Canada: Susan Cooke, (Western Ontario, CA); John A. Daly (Illinois, U-C); Francis W. Keenan, (Illinois, U-C); Robert G. Osterhoudt (Illinois, U-C); George Patrick (Illinois, U-C); Kathleen Pearson (Illinois, U-C); Sean Seaman (Western Ontario, CA; Danny Rosenberg (Western Ontario, CA); Debra Shogan (Western Ontario, CA); Peter Spencer-Kraus (Illinois, UC) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the mid-1960s, Dr. Paul Weiss, Heffer Professor of Philosophy, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, offered wise words of counsel to me on numerous occasions, as did Prof. Dr. Hans Lenk, a "world scholar" from the University of Karlsruhe, Germany, who has been a friend and colleague for whom I have the greatest of admiration. Dr. Warren Fraleigh, SUNY at Brockport, and Dr. Scott Kretchmar. of The Pennsylvania State University have been colleagues, scholars, and friends who haven't forgotten their roots in the physical education profession. -

Mtv and Transatlantic Cold War Music Videos

102 MTV AND TRANSATLANTIC COLD WAR MUSIC VIDEOS WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH INTRODUCTION In 1986 Music Television (MTV) premiered “Peace Sells”, the latest video from American metal band Megadeth. In many ways, “Peace Sells” was a standard pro- motional video, full of lip-synching and head-banging. Yet the “Peace Sells” video had political overtones. It featured footage of protestors and police in riot gear; at one point, the camera draws back to reveal a teenager watching “Peace Sells” on MTV. His father enters the room, grabs the remote and exclaims “What is this garbage you’re watching? I want to watch the news.” He changes the channel to footage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the 1986 nuclear arms control summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. The son, perturbed, turns to his father, replies “this is the news,” and lips the channel back. Megadeth’s song accelerates, and the video re- turns to riot footage. The song ends by repeatedly asking, “Peace sells, but who’s buying?” It was a prescient question during a 1980s in which Cold War militarism and the nuclear arms race escalated to dangerous new highs.1 In the 1980s, MTV elevated music videos to a new cultural prominence. Of course, most music videos were not political.2 Yet, as “Peace Sells” suggests, dur- ing the 1980s—the decade of Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and a robust nuclear arms race—music videos had the potential to relect political concerns. MTV’s founders, however, were so culturally conserva- tive that many were initially wary of playing African American artists; addition- ally, record labels were hesitant to put their top artists onto this new, risky chan- 1 American President Ronald Reagan had increased peace-time deicit defense spending substantially. -

'The Denial of Bivalence Is Absurd'1

On ‘The Denial of Bivalence is Absurd’1 Francis Jeffry Pelletier Robert J. Stainton University of Alberta Carleton University Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Timothy Williamson, in various places, has put forward an argument that is supposed to show that denying bivalence is absurd. This paper is an examination of the logical force of this argument, which is found wanting. I. Introduction Let us being with a word about what our topic is not. There is a familiar kind of argument for an epistemic view of vagueness in which one claims that denying bivalence introduces logical puzzles and complications that are not easily overcome. One then points out that, by ‘going epistemic’, one can preserve bivalence – and thus evade the complications. James Cargile presented an early version of this kind of argument [Cargile 1969], and Tim Williamson seemingly makes a similar point in his paper ‘Vagueness and Ignorance’ [Williamson 1992] when he says that ‘classical logic and semantics are vastly superior to…alternatives in simplicity, power, past success, and integration with theories in other domains’, and contends that this provides some grounds for not treating vagueness in this way.2 Obviously an argument of this kind invites a rejoinder about the puzzles and complications that the epistemic view introduces. Here are two quick examples. First, postulating, as the epistemicist does, linguistic facts no speaker of the language could possibly know, and which have no causal link to actual or possible speech behavior, is accompanied by a litany of disadvantages – as the reader can imagine.