Lost in Litigation: Untold Stories of a Title Ix Lawsuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks E2251 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

November 19, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E2251 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS IN HONOR OF JANIS KING ARNOLD TRIBUTE TO MAJOR GENERAL Knight Order Crown of Italy; and decorations JOHN E. MURRAY from the Korean and Vietnamese Govern- ments. HON. DENNIS J. KUCINICH HON. BILL PASCRELL, JR. Madam Speaker, I was truly saddened by the death of General Murray. I would like to OF OHIO OF NEW JERSEY extend my deepest condolences to his family. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES My thoughts and prayers are with his daughter Wednesday, November 19, 2008 Valerie, of Norfolk Virgina, his granddaughter Wednesday, November 19, 2008 Shana and grandson Andrew of Norfolk Vir- Mr. PASCRELL. Madam Speaker, I rise ginia; his brother Danny of Arlington Virginia, Mr. KUCINICH. Madam Speaker, I rise today to honor the life and accomplishments and a large extended family. today in honor of Janis King Arnold, and in of veteran, civil servant, and author Major General John E. Murray (United States Army f recognition of 36 outstanding years of service Retired). HONORING REVEREND DR. J. in the Cleveland Metro School District. She Born in Clifton, New Jersey, November 22, ALFRED SMITH, SR. has been instrumental in bringing innovative 1918, General Murray was drafted into the educational programs to the Greater Cleve- United States Army in 1941 as a private leav- HON. BARBARA LEE land Area. ing his studies at St. John’s University and OF CALIFORNIA rose to the rank of Major General. The career Janis Arnold has a multifaceted and rich his- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES tory in public service and recently retired from that followed was to take him through three Wednesday, November 19, 2008 a long and illustrious career in the Cleveland wars, ten campaigns and logistic and transpor- tation operations throughout the world. -

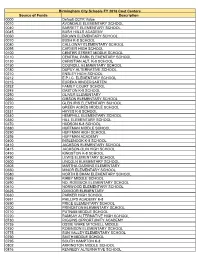

Source of Funds Description 0000 Default

Birmingham City Schools FY 2018 Cost Centers Source of Funds Description 0000 Default CCTR Value 0010 AVONDALE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0040 BARRETT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0045 BUSH HIILLS ACADEMY 0050 BROWN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0070 BUSH K-8 SCHOOL 0080 CALLOWAY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0095 CARVER HIGH SCHOOL 0100 CENTER STREET MIDDLE SCHOOL 0110 CENTRAL PARK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0130 CHRISTIAN ALT. K-8 SCHOOL 0150 COUNCILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0180 DUPUY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 0210 ENSLEY HIGH SCHOOL 0212 E.P.I.C. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0215 EUREKA KINDERGARTEN 0232 FAMILY COURT SCHOOL 0245 GASTON K-8 SCHOOL 0250 OLIVER ELEMENTARY 0260 GIBSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0270 GLEN IRIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0320 GREEN ACRES MIDDLE SCHOOL 0331 HAYES K-8 SCHOOL 0340 HEMPHILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0350 HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0370 HUDSON K-8 SCHOOL 0380 HUFFMAN MIDDLE SCHOOL 0390 HUFFMAN HIGH SCHOOL 0395 HUFFMAN ACADEMY 0400 INGLENOOK K-8 SCHOOL 0410 JACKSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0415 JACKSON-OLIN HIGH SCHOOL 0450 KINGSTON K-8 SCHOOL 0490 LEWIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0500 LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0505 MARTHA GASKINS ELEMENTARY 0550 MINOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0580 NORTH B BHAM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0585 KIRBY MIDDLE SCHOOL 0590 NO. ROEBUCK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0610 NORWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0625 OXMOOR ELEMENTARY 0630 PARKER HIGH SCHOOL 0651 PHILLIPS ACADEMY K-8 0690 PRICE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0700 PRINCETON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0710 PUTNAM MIDDLE SCHOOL 0720 RAMSAY ALTERNATIVE HIGH SCHOOL 0730 RIGGINS OPPORTUNITY ACADEMY 0735 OSSIE WARE MITCHELL MIDDLE 0750 ROBINSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0775 SUN VALLEY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0790 SMITH MIDDLE SCHOOL 0795 SOUTH HAMPTON K-8 0802 ARRINGTON MIDDLE SCHOOL 0816 KENNEDY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 0830 TUGGLE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0850 WASHINGTON K-8 SCHOOL 0857 JONES VALLEY MIDDLE SCHOOL 0858 WENONAH HIGH SCHOOL 0880 WEST END ACADEMY 0890 WHATLEY K-8 SCHOOL 0900 WILKERSON MIDDLE SCHOOL 0920 WOODLAWN HIGH SCHOOL 0930 WYLAM K-8 SCHOOL 1110 SUMMER SCHOOL CENTRAL PARK 7001 EASTERN AREA CROSSING GUARDS 7002 WESTERN AREA CROSSING GUARDS 8100 INSTRUCTION POOLED COST CENTER 8102 INSTRUCTIONAL BROADCAST SERV. -

1 Steven H. Hobbs1 I Plucked My

INTRODUCTION ALABAMA’S MIRROR: THE PEOPLE’S CRUSADE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS Steven H. Hobbs1 I plucked my soul out of its secret place, And held it to the mirror of my eye To see it like a star against the sky, A twitching body quivering in space, A spark of passion shining on my face. from I Know by Soul, by Claude McKay2 On April 4, 2014, The University of Alabama School of Law hosted a symposium on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The papers presented at that symposium are included in this issue of the Alabama Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review. The symposium was an opportunity to reflect on the reasons and history behind the Act, its implementation to make real the promises of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and the continuing urgency to make the principles of the Act a reality. We, in essence, plucked out the soul of our constitutional democracy’s guarantee of equality under the law and held it up for self-reflection. In introducing the symposium, I note the description that appeared in the program stating the hope for the event: This symposium is a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The passage of the Act marked the beginning of a new era of American public life. At the time it was enacted, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was perceived by many to be the codified culmination of decades of 1 Tom Bevill Chairholder of Law, University of Alabama School of Law. -

Of 80 Greenwood Garden Club

Tingle, Larry D.: Newspaper Obituary and Death Notice Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities (Minneapolis, MN) - July 17, 2011 Deceased Name: Tingle, Larry D. Tingle, Larry D. age 71, of Champlin, passed away on July 12, 2011. Retired longtime truck driver for US Holland. He was an avid fisherman and pheasant hunter. Preceded in death by his son, Todd; parents and 4 siblings. He will be deeply missed by his loving wife of 45years, Darlene; children, Deborah (Doug) Rutledge, Suzanne (Brian) Murray, Karen Emery, Tamara (Matt) Anderson, Melissa (John) O'Laughlin; grandchildren, Mark (Megan), Carrie (Ben), Rebecca (Travis), Christine (Blake), Jason (Emily), Brent (Mandy), Shane, Jenna, Nathan, Alexa; step- grandchildren, Megann and Dylan; 2 great-grandchildren, James and Alison; sister, Marvis Godber of South Dakota; many nieces, nephews, relatives and good friends. Memorial Service 11 am Saturday, July 23, 2011 at Champlin United Methodist Church, 921 Downs Road, Champlin (763-421-7047) with visitation at church 1 hour before service. www.cremationsocietyofmn.com 763-560-3100 photoEdition: METRO Page: 08B Copyright (c) 2011 Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities Freida Tingle Bonner: Newspaper Obituary and Death Notice Winona Times & Conservative, The (Winona, Carrolton, MS) - July 15, 2011 Deceased Name: Freida Tingle Bonner GREENWOOD - Freida Tingle Bonner passed away Monday, July 11, 2011, at University Medical Center in Jackson. Services were held at 3 p.m. Wednesday, July 13, 2011, at Wilson and Knight Funeral Chapel with burial in Odd Fellows Cemetery in Greenwood. Visitation was held from 1 until 3 p.m. prior to the service on Wednesday. -

“Stony the Road We Trod . . .” Exploring Alabama’S Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute

Dear Colleague Letter: “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute July 11- 31, 2021 Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha Bouyer, Project Developer and Director Mrs. Laura Anderson, Project Administrator Mrs. Evelyn Davis, Administrative Assistant 205-558-3980 [email protected] DISCLAIMER: “THE STONY . .” INSTITUTE WILL BE OFFERED AS A RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM BARRING TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS RELATED TO THE SPREAD OF COVID19. “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy National Teacher Institute Presented By: Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, Project Director Table of Contents Dear Colleague Letter...................................................................................................................1 Overview of the Institute Activities and Assignments ..............................................................4 Host City - Birmingham ............................................................................................................... 4 The Civil Rights Years.................................................................................................................. 5 “It Began at Bethel” ...................................................................................................................... 5 Selma and Montgomery Alabama ............................................................................................... 7 Tuskegee Alabama ....................................................................................................................... -

“Stony the Road We Trod . . .” Exploring Alabama's Civil Rights

Dear Colleague Letter: “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute July 11- 31, 2021 Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha Bouyer, Project Developer and Director Mrs. Laura Anderson, Project Administrator Mrs. Evelyn Davis, Administrative Assistant 205-558-3980 [email protected] DISCLAIMER: “THE STONY . .” INSTITUTE WILL BE OFFERED AS A RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM BARRING TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS RELATED TO COVID19. “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy National Teacher Institute Presented By: Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, Project Director Table of Contents Dear Colleague Letter...................................................................................................................1 Overview of the Institute Activities and Assignments ..............................................................4 Host City - Birmingham ............................................................................................................... 4 The Civil Rights Years.................................................................................................................. 5 “It Began at Bethel” ...................................................................................................................... 5 Selma and Montgomery Alabama ............................................................................................... 7 Tuskegee Alabama ....................................................................................................................... -

The John Herbert Phillips High School Birmingham, Alabama

The John Herbert Phillips High School Birmingham, Alabama Assessment of Eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) Thomas M. Shelby The University of Alabama Museums Office of Archaeological Research 13075 Moundville Archaeological Park Moundville, Alabama 35474 September 2005 September 26, 2005 Assessment of Eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) for the John Herbert Phillips High School in Birmingham OAR PROJECT NUMBER: 05-214 PERFORMED FOR: Birmingham, Historical Society One Sloss Quarters Birmingham, Alabama 35222 Attn: Mrs. Majorie L. White PERFORMED BY: Thomas M. Shelby, Cultural Resources Technician Gene A. Ford, Cultural Resources Investigator John F. Lieb, Cultural Resources Assistant The University of Alabama Office of Archaeological Research 13075 Moundville Archaeological Park Moundville, Alabama 35474 DATE PERFORMED: September 9, 2005 ___________________________ __________________________ Thomas M. Shelby Robert A. Clouse, Ph.D./Director Cultural Resources Technician The University of Alabama Office of Archaeological Research Office of Archaeological Research The John Herbert Phillips High School Birmingham, Alabama Assessment of Eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) Thomas M. Shelby Introduction The John Herbert Phillips High School is a basement and three-story Jacobethan Style school building that served as the centerpiece of the Birmingham school system from 1923 through 2001. Located between 7th and 8th Avenues North and 23rd and 24th Streets (Figure 1), Phillips High School occupies an entire city block. It was designed in 1920 by prominent Birmingham architect D.O. Whilldin, and was built in two phases: the first unit in 1923 and the second unit in 1925. Today the building is remarkably well preserved and retains much of its integrity, including both exterior and interior details. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama Southern Division

Case 2:08-cv-00031-WMA Document 59 Filed 12/17/09 Page 1 of 42 FILED 2009 Dec-17 PM 02:34 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION BILLY CULVER, } } Plaintiff, } } CIVIL ACTION NO. v. } 08-AR-0031-S } BIRMINGHAM BOARD OF } EDUCATION, et al., } } Defendants. } MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff, Billy Culver (“Culver”), instituted the above- entitled action against the Birmingham Board of Education (“BBOE”), Odessa Ashley (“Ashley”), Carolyn Cobb (“Cobb”), Mike Higginbotham (“Higginbotham”), Willie James Maye (“Maye”), Dannetta Owens (“Owens”), Virginia Volker (“Volker”), April Williams (“Williams”), and Phyllis Wyne (“Wyne”) in their individual and official capacities as members of the Birmingham Board of Education, as well as against Stan L. Mims (“Mims”) and Wayman Shiver (“Shiver”) in their individual and official capacities as former Superintendents of the Birmingham City Schools system (collectively “defendants”). Both former superintendents and a majority of the BBOE members are black. Culver, who is white, alleges that he was the subject of racial discrimination in defendants’ decisions not to hire, transfer, or promote him to numerous positions for which he applied, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., and in violation of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 Case 2:08-cv-00031-WMA Document 59 Filed 12/17/09 Page 2 of 42 and 1983. Culver also claims that he was retaliated against by defendants, in violation of both Title VII and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (the Patsy T. -

Attempts at Desegregation and to Describe the Processvhat Led to Their Effedtiveness And/Or Success

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 275 95 UD 015 679 AUTHOR Bynum; Effie; And Others TITLE Desegregation in Birmingham, Alabama: A Case Study. _INSTITUTION Columbia Univ., New York, N.Y. 7eaChers College. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 74 NE-G-00-3-0156 NOTE 188p. EDRS 'PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$9.51 PluS Postage kip "DESCRIPTORS Administrator Attitudes; *Case Studies; Community Attitudes; *Field Interviews; Integration Effects; *Integration Studies; Observation; Parent Attitudes; Radial Integration; Research Methodology; *School Integration; School Visitation; Student Attitudes; Teacher Attitudes .IDENTIFIERS *Alabama (Birminghai) ABSTRACT In May, 1974, a five member study team from Teachers College,' Columbia University spent four and one-half days in Birmirigham, Alabama, for the purpose of (1) collecting information that describes the desegregation process as it evolved,. (2) interviewing principals, administrators, teachers, students and community leaders relative to their impressions of the desegregation move and its impact, and(3) observing random classrooms, hallways, cafetettias, and playgrounds of 12 selected schools. Birmingham City . School District was selected to participate in this study because it was identifie from a collection of resource data as a district that developed and/mplemented a conflict;free (the current plan) and -effective plan. The/major, purpose of the overall project was to -identify districts that have been effective and successful in their attempts at desegregation and to describe the processVhat led to their effedtiveness and/or success. The Birmingham sam included schools (1) with an almost equal distribution of black and white students,(2) those having both a 60 percent black and white population,,(3) those having almost an 80 percent black and white enrollment, and,(4) those that had all black students and several having an almost all white student body. -

Education and Workforce Committee 2018 Mayoral Transition Report

Education and Workforce Committee 2018 Mayoral Transition Report 2018 Mayoral Transition Report Education and Workforce Committee I. Scope of Review Education and Workforce Development constitutes the core means by which we prepare our children to succeed in life. One cannot exist without the other. A high quality education is essential in preparing students to graduate from high school or college, ready to enter the workforce and support an even higher quality of life. An intense and collaborative focus of workforce needs, generated from employers and the general marketplace, are required in order for students to understand where their brightest future may lie. The two efforts, however, must work closely together in order to provide our children the greatest hope and opportunity for success. The Education and Workforce Committee (EWC) has examined both education and workforce development in Birmingham and the region surrounding it. The Committee has focused on how the Mayor’s Office can provide constructive support to both Education and Workforce Development efforts. It has become clear that the City is in need of cooperation, support, and most of all, leadership. While there is no lack of workforce programming among regional agency and community partners, the EWC sees a lack of cohesion among their various efforts and targeted goals. With that said, Birmingham would thrive from a city-led workforce development program to be facilitated from the Mayor’s Office, with dedicated personnel and resources that offers cross-system collaborations with city and state government, non-profit organizations, education entities, and the business community. Building on successes such as Innovate Birmingham, the Mayor’s office should expand public/private partnerships to accomplish the recommendations and goals in this report. -

Volume 7, Number 1 {Winter/Spring 2005}

Volume 7, Number 1 {Winter/Spring 2005} Beginning with this issue, You Make The Call. will now provide analysis of the most recent cases in the sports law field on a bi-annual basis. Each issue will cover the past 6 months of cases. The current issue covers cases from January 1 to June 30, 2005. Issue 2 will cover cases from July 1 to December 31, 2005, and will be published in January of 2006. Where available we continue to include "Webfinds" that provide a pinpoint website link to copies of the cases included in the newsletter. Agency Law Biktasheva v. Red Square Sports, Inc., 366 F. Supp. 2d 289 (D. Md 2005). Professional athletes, Lyudmila Biktasheva and Silviya Skvortsova were represented by Red Square Sports, Inc. When Red Square Sports paid the athletes a fraction of the amount owed under their Nike endorsement contracts, they sued for breach of contract. The court granted Red Square Sport's motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction because the claim did not satisfy the amount in controversy requirement for diversity jurisdiction. The athletes' claimed they were each owed $36,000, while the jurisdictional requirement is for claims valued at $75,000. Fittipaldi USA, Inc. v. Castroneves, 905 So. 2d 182 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2005). Racecar driver, Helio Castroneves was represented by FUSA, a subsidiary of Fittipaldi USA, Inc. Castroneves terminated the representation agreement after FUSA failed to assist him in © Copyright 2005, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 obtaining a spot on a racing team. -

North Atlantic Regional Business Law Association

Published by Husson College Bangor, Maine For the NORTH ATLANTIC REGIONAL BUSINESS LAW ASSOCIATION EDITOR IN CHIEF William B. Read Husson College BOARD OF EDITORS Robert C. Bird Gerald A. Madek University of Connecticut Bentley College Leslie H. Brooks Carter H. Manny Nichols College University of Southern Maine Gerald R. Ferrera Christine N. O’Brien Bentley College Boston College Stephanie M. Greene Lucille M. Ponte Boston College University of Central Florida William E. Greenspan Margo E.K. Reder University of Bridgeport Boston College Anne-Marie G. Harris David Silverstein Salem State College Suffolk University Stephen D. Lichtenstein Edwin W. Tucker Bentley College Emeritus David P. Twomey Boston College i GUIDELINES FOR PUBLICATION Papers presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting and Conference will be considered for publication in the Business Law Review. In order to permit blind refereeing of manuscripts for the 2006 Business Law Review, papers must not identify the author or the author’s institutional affiliation. A removable cover page should contain the title, the author’s name, affiliation, and address. If you are presenting a paper and would like to have it considered for publication, you must submit two clean copies, no later than March 31, 2006 to: Professor William B. Read Husson College 1 College Circle Bangor, Maine 04401 The Board of Editors of the Business Law Review will judge each paper on its scholarly contribution, research quality, topic interest (related to business law or the legal environment), writing quality, and readiness for publication. Please note that, although you are welcome to present papers relating to teaching business law, those papers will not be eligible for publication in the Business Law Review.