ED 128 546 DOCUMENT RESUME UD 016 473 AUTHOR Gordon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

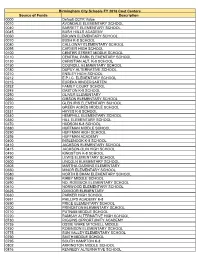

Source of Funds Description 0000 Default

Birmingham City Schools FY 2018 Cost Centers Source of Funds Description 0000 Default CCTR Value 0010 AVONDALE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0040 BARRETT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0045 BUSH HIILLS ACADEMY 0050 BROWN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0070 BUSH K-8 SCHOOL 0080 CALLOWAY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0095 CARVER HIGH SCHOOL 0100 CENTER STREET MIDDLE SCHOOL 0110 CENTRAL PARK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0130 CHRISTIAN ALT. K-8 SCHOOL 0150 COUNCILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0180 DUPUY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 0210 ENSLEY HIGH SCHOOL 0212 E.P.I.C. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0215 EUREKA KINDERGARTEN 0232 FAMILY COURT SCHOOL 0245 GASTON K-8 SCHOOL 0250 OLIVER ELEMENTARY 0260 GIBSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0270 GLEN IRIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0320 GREEN ACRES MIDDLE SCHOOL 0331 HAYES K-8 SCHOOL 0340 HEMPHILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0350 HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0370 HUDSON K-8 SCHOOL 0380 HUFFMAN MIDDLE SCHOOL 0390 HUFFMAN HIGH SCHOOL 0395 HUFFMAN ACADEMY 0400 INGLENOOK K-8 SCHOOL 0410 JACKSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0415 JACKSON-OLIN HIGH SCHOOL 0450 KINGSTON K-8 SCHOOL 0490 LEWIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0500 LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0505 MARTHA GASKINS ELEMENTARY 0550 MINOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0580 NORTH B BHAM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0585 KIRBY MIDDLE SCHOOL 0590 NO. ROEBUCK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0610 NORWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0625 OXMOOR ELEMENTARY 0630 PARKER HIGH SCHOOL 0651 PHILLIPS ACADEMY K-8 0690 PRICE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0700 PRINCETON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0710 PUTNAM MIDDLE SCHOOL 0720 RAMSAY ALTERNATIVE HIGH SCHOOL 0730 RIGGINS OPPORTUNITY ACADEMY 0735 OSSIE WARE MITCHELL MIDDLE 0750 ROBINSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0775 SUN VALLEY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0790 SMITH MIDDLE SCHOOL 0795 SOUTH HAMPTON K-8 0802 ARRINGTON MIDDLE SCHOOL 0816 KENNEDY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 0830 TUGGLE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0850 WASHINGTON K-8 SCHOOL 0857 JONES VALLEY MIDDLE SCHOOL 0858 WENONAH HIGH SCHOOL 0880 WEST END ACADEMY 0890 WHATLEY K-8 SCHOOL 0900 WILKERSON MIDDLE SCHOOL 0920 WOODLAWN HIGH SCHOOL 0930 WYLAM K-8 SCHOOL 1110 SUMMER SCHOOL CENTRAL PARK 7001 EASTERN AREA CROSSING GUARDS 7002 WESTERN AREA CROSSING GUARDS 8100 INSTRUCTION POOLED COST CENTER 8102 INSTRUCTIONAL BROADCAST SERV. -

1 Steven H. Hobbs1 I Plucked My

INTRODUCTION ALABAMA’S MIRROR: THE PEOPLE’S CRUSADE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS Steven H. Hobbs1 I plucked my soul out of its secret place, And held it to the mirror of my eye To see it like a star against the sky, A twitching body quivering in space, A spark of passion shining on my face. from I Know by Soul, by Claude McKay2 On April 4, 2014, The University of Alabama School of Law hosted a symposium on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The papers presented at that symposium are included in this issue of the Alabama Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review. The symposium was an opportunity to reflect on the reasons and history behind the Act, its implementation to make real the promises of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and the continuing urgency to make the principles of the Act a reality. We, in essence, plucked out the soul of our constitutional democracy’s guarantee of equality under the law and held it up for self-reflection. In introducing the symposium, I note the description that appeared in the program stating the hope for the event: This symposium is a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The passage of the Act marked the beginning of a new era of American public life. At the time it was enacted, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was perceived by many to be the codified culmination of decades of 1 Tom Bevill Chairholder of Law, University of Alabama School of Law. -

“Stony the Road We Trod . . .” Exploring Alabama’S Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute

Dear Colleague Letter: “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute July 11- 31, 2021 Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha Bouyer, Project Developer and Director Mrs. Laura Anderson, Project Administrator Mrs. Evelyn Davis, Administrative Assistant 205-558-3980 [email protected] DISCLAIMER: “THE STONY . .” INSTITUTE WILL BE OFFERED AS A RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM BARRING TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS RELATED TO THE SPREAD OF COVID19. “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy National Teacher Institute Presented By: Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, Project Director Table of Contents Dear Colleague Letter...................................................................................................................1 Overview of the Institute Activities and Assignments ..............................................................4 Host City - Birmingham ............................................................................................................... 4 The Civil Rights Years.................................................................................................................. 5 “It Began at Bethel” ...................................................................................................................... 5 Selma and Montgomery Alabama ............................................................................................... 7 Tuskegee Alabama ....................................................................................................................... -

“Stony the Road We Trod . . .” Exploring Alabama's Civil Rights

Dear Colleague Letter: “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute July 11- 31, 2021 Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha Bouyer, Project Developer and Director Mrs. Laura Anderson, Project Administrator Mrs. Evelyn Davis, Administrative Assistant 205-558-3980 [email protected] DISCLAIMER: “THE STONY . .” INSTITUTE WILL BE OFFERED AS A RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM BARRING TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS RELATED TO COVID19. “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy National Teacher Institute Presented By: Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, Project Director Table of Contents Dear Colleague Letter...................................................................................................................1 Overview of the Institute Activities and Assignments ..............................................................4 Host City - Birmingham ............................................................................................................... 4 The Civil Rights Years.................................................................................................................. 5 “It Began at Bethel” ...................................................................................................................... 5 Selma and Montgomery Alabama ............................................................................................... 7 Tuskegee Alabama ....................................................................................................................... -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama Southern Division

Case 2:08-cv-00031-WMA Document 59 Filed 12/17/09 Page 1 of 42 FILED 2009 Dec-17 PM 02:34 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION BILLY CULVER, } } Plaintiff, } } CIVIL ACTION NO. v. } 08-AR-0031-S } BIRMINGHAM BOARD OF } EDUCATION, et al., } } Defendants. } MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff, Billy Culver (“Culver”), instituted the above- entitled action against the Birmingham Board of Education (“BBOE”), Odessa Ashley (“Ashley”), Carolyn Cobb (“Cobb”), Mike Higginbotham (“Higginbotham”), Willie James Maye (“Maye”), Dannetta Owens (“Owens”), Virginia Volker (“Volker”), April Williams (“Williams”), and Phyllis Wyne (“Wyne”) in their individual and official capacities as members of the Birmingham Board of Education, as well as against Stan L. Mims (“Mims”) and Wayman Shiver (“Shiver”) in their individual and official capacities as former Superintendents of the Birmingham City Schools system (collectively “defendants”). Both former superintendents and a majority of the BBOE members are black. Culver, who is white, alleges that he was the subject of racial discrimination in defendants’ decisions not to hire, transfer, or promote him to numerous positions for which he applied, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., and in violation of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 Case 2:08-cv-00031-WMA Document 59 Filed 12/17/09 Page 2 of 42 and 1983. Culver also claims that he was retaliated against by defendants, in violation of both Title VII and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (the Patsy T. -

Attempts at Desegregation and to Describe the Processvhat Led to Their Effedtiveness And/Or Success

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117 275 95 UD 015 679 AUTHOR Bynum; Effie; And Others TITLE Desegregation in Birmingham, Alabama: A Case Study. _INSTITUTION Columbia Univ., New York, N.Y. 7eaChers College. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 74 NE-G-00-3-0156 NOTE 188p. EDRS 'PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$9.51 PluS Postage kip "DESCRIPTORS Administrator Attitudes; *Case Studies; Community Attitudes; *Field Interviews; Integration Effects; *Integration Studies; Observation; Parent Attitudes; Radial Integration; Research Methodology; *School Integration; School Visitation; Student Attitudes; Teacher Attitudes .IDENTIFIERS *Alabama (Birminghai) ABSTRACT In May, 1974, a five member study team from Teachers College,' Columbia University spent four and one-half days in Birmirigham, Alabama, for the purpose of (1) collecting information that describes the desegregation process as it evolved,. (2) interviewing principals, administrators, teachers, students and community leaders relative to their impressions of the desegregation move and its impact, and(3) observing random classrooms, hallways, cafetettias, and playgrounds of 12 selected schools. Birmingham City . School District was selected to participate in this study because it was identifie from a collection of resource data as a district that developed and/mplemented a conflict;free (the current plan) and -effective plan. The/major, purpose of the overall project was to -identify districts that have been effective and successful in their attempts at desegregation and to describe the processVhat led to their effedtiveness and/or success. The Birmingham sam included schools (1) with an almost equal distribution of black and white students,(2) those having both a 60 percent black and white population,,(3) those having almost an 80 percent black and white enrollment, and,(4) those that had all black students and several having an almost all white student body. -

Education and Workforce Committee 2018 Mayoral Transition Report

Education and Workforce Committee 2018 Mayoral Transition Report 2018 Mayoral Transition Report Education and Workforce Committee I. Scope of Review Education and Workforce Development constitutes the core means by which we prepare our children to succeed in life. One cannot exist without the other. A high quality education is essential in preparing students to graduate from high school or college, ready to enter the workforce and support an even higher quality of life. An intense and collaborative focus of workforce needs, generated from employers and the general marketplace, are required in order for students to understand where their brightest future may lie. The two efforts, however, must work closely together in order to provide our children the greatest hope and opportunity for success. The Education and Workforce Committee (EWC) has examined both education and workforce development in Birmingham and the region surrounding it. The Committee has focused on how the Mayor’s Office can provide constructive support to both Education and Workforce Development efforts. It has become clear that the City is in need of cooperation, support, and most of all, leadership. While there is no lack of workforce programming among regional agency and community partners, the EWC sees a lack of cohesion among their various efforts and targeted goals. With that said, Birmingham would thrive from a city-led workforce development program to be facilitated from the Mayor’s Office, with dedicated personnel and resources that offers cross-system collaborations with city and state government, non-profit organizations, education entities, and the business community. Building on successes such as Innovate Birmingham, the Mayor’s office should expand public/private partnerships to accomplish the recommendations and goals in this report. -

Lost in Litigation: Untold Stories of a Title Ix Lawsuit

LOST IN LITIGATION: UNTOLD STORIES OF A TITLE IX LAWSUIT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kylee Jo Short, M.A. Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sarah K. Fields, Advisor Dr. Melvin Adelman Dr. Brian Turner Copyrighted by Kylee Jo Short 2012 Abstract Girls and women in the United States are more active participants of sport than ever before. Many attribute this dramatic increase to the impact of Title IX, the legislation that requires gender equity in educational settings. However, Title IX is proving just to be the first step, as it does not address all of the issues. Namely, application of the law skips over the fact that poor women of color are ultimately left out of the equation. Women and girls of color are not “winning” the Title IX game like white women and girls. On the contrary, the application of Title IX ignores poor, black females. The purpose of this project is to fill the void left by ignoring poor girls of color by considering the voices that are often lost in Title IX fights. In considering the most recent lawsuit to reach the Supreme Court, Jackson v. Birmingham Board of Education, I explore the impact of this Title IX lawsuit on the Birmingham community. Through interviews with several involved in this lawsuit—Coach Jackson, three of his former players, a parent, a student, and an athletic administrator—I provide several angles on how Title IX played out at the local level. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with James Roberson

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with James Roberson Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Roberson, James, 1943- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with James Roberson, Dates: March 21, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 6 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:34:35). Description: Abstract: Auto sales entrepreneur and high school administrator James Roberson (1943 - ) served as an educator and administrator for the Alabama Board of Education. He then became the first African American with a Pontiac car dealership. Roberson then became owner of USA Auto and Budget Truck Rental Store in 2000 until his retirement in 2003. Roberson was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on March 21, 2007, in Birmingham, Alabama. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_104 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® James Earnest Roberson was born on June 14, 1943 to Aressa and Mack E. Roberson in Birmingham, Alabama. Roberson’s parents were activists and involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Roberson lived across the street from Bethel Baptist Church, home to Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth, that was twice- bombed by the Ku Klux Klan. Roberson attended A.H. Parker High School where he graduated with an advance academic honors diploma in 1960. He received his B.A. degree in secondary education from Alabama A&M University in 1964; his M.A. degree in educational leadership in 1986 from University of Alabama; and his J.D. -

Our Beginning in 1959

The History of the Speech and Hearing Association of Alabama 1959-2003 Compiled by Dr. Loretta G. Brown Table of Contents About this History ........................................................................................................................1 The Beginning .............................................................................................................................2 Charter Members ........................................................................................................................3 Presidents ...................................................................................................................................4 Dr. J. Buckminster Ranney ............................................................................................4 Dr. William P. Dorne’......................................................................................................6 Dr. Thomas G. Giolas ....................................................................................................8 Miss Vivian I Roe .........................................................................................................10 Mrs. Louise Ward.........................................................................................................14 Dr. Robert E. Roach.....................................................................................................16 Dr. Elizabeth Webster ..................................................................................................18 Dr. David -

Annual Report 2013

2013$118$/5(3257 ANNUAL REPORT Library Board, Staff Supporters, Partners Library Trustees Birmingham Public Library Young Professionals Gwendolyn R. Amamoo, President Leah Bigbee Georgia Morgan Blair, Vice-President Sonya Boatwright The Honorable Judge Scott Vowell, Parliamentarian Ernest Burnley Dr. Monique Gardner-Witherspoon Fatima Carter Patty A. Pilkerton Ellen Chandler Kimberly Richardson Jonathan Coleman Samuel A. Rumore, Jr. Yawntreshia Coleman Dora Sims Tiffeny Curier Katrina Watson William Dahlberg Gwendolyn B. Guster Welch Sheetal Desai Rikesha Foster Kay Garner Library Administration Brent Godwin Irene S. Blalock, Library Director Steven Hallmark Angela Fisher Hall, Associate Library Director Jeniese Hosey Natasha Ivory Maree Jones Birmingham Public Library Foundation Theresa Jones James H. White, III, President Rashada LeRoy David Herring, Vice-President Laura Lieb John Coleman Blair Liggins Liesel French Deidra Mayes Sol Kimerling Sabrina Mays Tony Smoke Clair McLafferty Renee Blalock, Library Director Cassandra McLendon Regina Ammon, Friends President Charlotte McLendon Gwendolyn R. Amamoo, Board President Tevis Owens James Sullivan, YP President Eryka Perry Meredith Ryan Cassandra Spencer Friends of the Birmingham Public Library Kristy Stewart Regina Ammon, President Brandan Stuckey Cheryl Burgess, Secretary James Sullivan, President Michelle Horn Brown Erin Welch Courtney Pigford Carla Jean Whitley KP Targe Adrian Zebot Dafina Ward 1 Remembering a Movement That Changed the World: Birmingham Public Libraries Reflect and Celebrate 50 Years Forward As the City of Birmingham prepared to mark fifty years since the start of its own civil rights movement, the Birmingham Public Library (BPL) looked for ways in which it could add to the celebration. Eager staff members focused on connecting annual public programs to themes promoting civil rights. -

We're Going Too!

“We’re Going Too!” The Children of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gisell Jeter-Bennett, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Lilia Fernández Judy Wu Copyright by Gisell Jeter-Bennett 2016 Abstract In 1963, the Birmingham, Alabama civil rights movement brought both national and international attention to the plight of southern African Americans. The Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), in partnership with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), utilized nonviolent direct action – marches, sit- ins, jail-ins, and boycotts- to challenge Birmingham’s discriminatory laws and practices. The success of the Birmingham campaign was due in large part to the participation and personal sacrifice of black schoolchildren. This dissertation examines the local Birmingham movement from the perspective of its most indispensible participants, black youth. It explores what it meant to be a black child coming of age under Jim Crow. It analyzes the recruitment, participation, and impact of Birmingham black youth in the Children’s March, a weeklong protest from May 2 to May 7, 1963, during which over 2,000 children between ages six and eighteen marched through Birmingham’s streets in nonviolent protest against racial inequality. It also looks anew at the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, which led to the deaths of four black school-aged girls, and the subsequent killing of two black boys.