Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramayana of * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH with EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY

THE Ramayana OF * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH WITH EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY (. ^ ^reenivasa jHv$oiu$ar, B. A., LECTURER S. P G. COLLEGE, TRICHINGj, Balakanda and N MADRAS: * M. K. PEES8, A. L. T. PRKS8 AND GUARDIAN PBE8S. > 1910. % i*t - , JJf Reserved Copyright ftpfiglwtd. 3 [ JB^/to PREFACE The Ramayana of Valmeeki is a most unique work. The Aryans are the oldest race on earth and the most * advanced and the is their first ; Ramayana and grandest epic. The Eddas of Scandinavia, the Niebelungen Lied of Germany, the Iliad of Homer, the Enead of Virgil, the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso of Dante, the Paradise Lost of Milton, the Lusiad of Camcens, the Shah Nama of Firdausi are and no more the Epics ; Ramayana of Valmeeki is an Epic and much more. If any work can clam} to be the Bible of the Hindus, it is the Ramayana of Valmeeki. Professor MacDonell, the latest writer on Samskritha Literature, says : " The Epic contains the following verse foretelling its everlasting fame * As long as moynfain ranges stand And rivers flow upon the earth, So long will this Ramayana Survive upon the lips of men. This prophecy has been perhaps even more abundantly fulfilled than the well-known prediction of Horace. No pro- duct of Sanskrit Literature has enjoyed a greater popularity in India down to the present day than the Ramayana. Its story furnishes the subject of many other Sanskrit poems as well as plays and still delights, from the lips* of reciters, the hearts of the myriads of the Indian people, as at the 11 PREFACE great annual Rama-festival held at Benares. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5022

12 NAGARi ALPHABET, SIGNS AND SYMBOLS OF PARAMARA INSCRIPTIONS Arvind K. Singh The Paramaras, started their political career the scribe and the engraver was performed by the in the ninth century C.E. as feudatories of the same person. The relevant epigraphic data provide 1 imperial Racmrak0[)'ls1monarch , succeeded in significant details concerning these professionals, 1 building a strong kingdom in the heart of the central and sometimes mention their predecessors as well , India in the tenth century and played a leading as native place, role, occupation and designation j role in the history of the country till fourteenth as applied to poets, scribes and engravers. It is century C.E. During the course of their political obvious from the examples of good epigraphic I' existence, the Paramaras ruled over various poetry that high talented poets were employed for territories, which includes Maiava proper as well composing the inscriptions. The poets were 1 the adjacent districts of Vidisha in the east, Ratlam honored by different ways, even by donating land. in the west, Indore and the parts of Hoshangabad AtrO stone inscription of the time of JayasiAha: in the south-east. In addition the imperial royal V.S. 1314 (C.E. 1258) records the donation by house of Maiava, there was other contemporary JayasiAhadeva of the village Mhaisada (Bhainra) royal houses of the Paramaras over Arbuda in the territorial division of PaAvimha in favor of a manda, Maru-mandala, Jalor, and Vaga. The kavicakravartin, mhakkura NarayaGa (no. 55). house that grew to power in the region around · Tilakwada copper-plate inscription of the time of Arbuda-maandala or Mount Abo, subsequently Bhojadeva: V.S. -

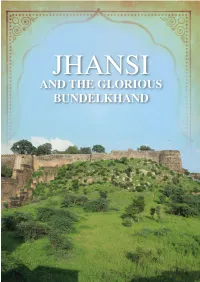

Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through the Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857?

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through The Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857? Attractions in and around Jhansi Jhansi Fort Rani Mahal Ganesh Mandir Mahalakshmi Temple Gangadharrao Chhatri Star Fort Jokhan Bagh St Jude’s Shrine Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery Jhansi Railway Station Orchha I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi is one of the most vibrant cities of Uttar Pradesh today. But the city is also steeped in history. The city of Rani Laxmibai - the brave queen who led her forces against the British in 1857 and the region around it, are dotted with monuments that go back more than 1500 years! While thousands of tourists visit Jhansi each year, many miss the layered past of the city. In fact, few who visit the famous Jhansi Fort each year, even know that it is in its historic Ganesh Mandir that Rani Laxmibai got married. Or that there is also a ‘second’ Fort hidden within the Jhansi cantonment, where the revolt of 1857 first began in the city. G L I M P S E S O F J H A N S I ’ S H I S T O R Y JHANSI THROUGH THE AGES Jhansi, the historic town and major tourist draw in Uttar Pradesh, is known today largely because of its famous 19th-century Queen, Rani Laxmibai, and the fearless role she played during the Revolt of 1857. There are also numerous monuments that dot Jhansi, remnants of the Bundelas and Marathas that ruled here from the 17th to the 19th centuries. -

New Kings and Kingdoms

History - Chapter 2 New Kings and Kingdoms Medieval Period Early Medieval Later Medieval Period 8th Period-12th Century to 12th Century to 18th Century Century Who were the new powers? How they became powerful? The Emergence of New Dynasties ● Rich landlords or warrior chiefs became subordinates of kings and were given title of samantas, and were expected to bring gifts for their kings or overlords, had to be present at their courts and would provide them military support. With more power and wealth, samantas became ‘maha-samanta’ or ‘mahamandaleshwar’, and some of them became free from their overlords. ● Dantidurga, who was a Rashtrakuta chief, performed ‘hiranyagarbha’ ritual to become a Kshatriya and then he overthrew his Chalukya overlord. ● In spite of being Brahmans, Kadamba Mayurasharman and Gurjara-Pratihara Harichandra built their kingdoms in Karnataka and Rajasthan. Prashastis and Land Grants ● Prashastis are a special kind of inscription, meaning “in praise of”. They were composed by learned Brahmanas in praise of the rulers, which may not be literally true; but, they tell us how rulers of that time wanted to illustrate themselves. ● If the kings liked the prashastis, they gave land as a gift to the Brahmans, with records of it on copper plates. ● Kalhana was a famous writer who wrote a long Sanskrit poem (Rajatarangini - "The River of Kings") on kings of Kashmir by using a variety of sources,such as inscriptions, documents, eyewitness accounts, and earlier histories. He was usually critical about rulers and their policies. Rajput ancestry can be divided between Suryavanshi (“House of the Sun,” or Solar people), or those descended from Rama, the hero of the epic Ramayana; and Chandravanshi (“House of the Moon,” or Lunar people), or those descended from Krishna, the hero of the epic Mahabharata. -

Asiatische Studien Etudes Asiatiques L U I • 1998

Schweizerische Asiengesellschaft Société Suisse-Asie 5 Asiatische Studien Etudes Asiatiques LUI • 1998 Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft Revue de la Société Suisse - Asie Peter Lang Bern • Berlin • Frankfurtam Main • New York • Paris • Wien ASIATISCHE STUDIEN ÉTUDES ASIATIQUES Herausgegeben von / Editées par JOHANNES BRONKHORST (Lausanne) - REINHARD SCHULZE (Bern) - ROBERT GASSMANN (Zürich) - EDUARD KLOPFENSTEIN (Zürich) - JACQUES MAY (Lausanne) - GREGOR SCHOELER (Basel) Redaktion: Ostasiatisches Seminar der Universität Zürich, Zürichbergstrasse 4, CH-8032 Zürich Die Asiatischen Studien erscheinen vier Mal pro Jahr. Redaktionstermin für Heft 1 ist der 15. September des Vorjahres, für Heft 2 der 15. Dezember, für Heft 3 der 15. März des gleichen Jahres und für Heft 4 der 15. Juni. Manuskripte sollten mit doppeltem Zeilenabstand geschrieben sein und im allgemeinen nicht mehr als vierzig Seiten umfassen. Anmerkungen, ebenfalls mit doppeltem Zeilenabstand geschrieben, und Glossar sind am Ende des Manuskriptes beizufügen (keine Fremdschriften in Text und Anmerkungen). Les Études Asiatiques paraissent quatre fois par an. Le délai rédactionnel pour le nu méro 1 est au 15 septembre de l’année précédente, pour le numéro 2 le 15 décembre, pour le numéro 3 le 15 mars de la même année et pour le numéro 4 le 15 juin. Les manuscrits doivent être dactylographiés en double interligne et ne pas excéder 40 pages. Les notes, en numérotation continue, également dactylographiées en double interligne, ainsi que le glossaire sont présentés à la fin du manuscrit. The Asiatische Studien are published four times a year. Manuscripts for publication in the first issue should be submitted by September 15 of the preceding year, for the second issue by December 15, for the third issue by March 15 and for the fourth issue by June 15. -

CHAPTER Onei BRIEF SURVEY of YADAVA's POLITICAL HISTORY

CHAPTER ONEi BRIEF SURVEY OF YADAVA’S POLITICAL HISTORY The early history of the Yadavas is shrouded in some „ 1 obscurity. It seems that the Yadavas were first known as Seunas and their dominion was called Seunadesa. The Sangamner copper plate of Yadava Billama II/2 and Hemadri also testifies that the 3 Seunadesa was known after the name of Seunachandra who was the son of Dridhapahara. Seunadesa was the name given to the region extending from Nasik to Devagiri. In the introduction to Hemadri's Vratakhanda Devagiri was situated in Seunadesa and that the latter was located 4 on the borders of Pandakaranya. 5 The Kalegaon inscription of Yadava Mahadeva/ shows that the country founded by Dridhapahara was extended by Seunachandra on both the banks of Godavari so as to include the modern districts of Aurangabad and east and west Khandesh together with portions of Ahmednagar and Nasik. As the records of dynasty traced its descent from the Puranic hero Yadu its rulers were better known as Yadavas although the word Seuna was not totally forgotten. The Muslim historians knew them as Yadavas and Prataparudriya of vidyanatha 6 refers to them as Yadava kings of Seuna country. Origin of the Yadava Family The early history of the Yadava dynasty is found in the epigraphic records of its rulers as well as in the introduction iiuiiiii 3 to the Hemadris Vratakhanda. Most of the inscriptions of the Yadava rulers refer that the family called Yadava originated 7 from the holy Vishnu's lineage. The Paithan grant of Ramachandra tracing the descent of the family states the followings From the lotus that grew from the navel of Vishnu# there was produced Viruchi. -

View / Download the Full Paper in a New

The Possession of Narratives: Telling and Transmitting Caste in Indian Folktales Siddharth N Kanoujia, University of Delhi, India The European Conference of Arts & Humanities 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This paper postulates that caste in India is not just a sociological category, or an existential reality, but has been historically constituted of narratives that shape both. It will elaborate this by offering a brief survey of the rich store of myths, fables and parables meant for the children that have emerged and been transmitted over a millenia in the subcontinent. These include the Jatakas , the Panchtantra , and the Hitopadesh – a few of its most famous examples. These stories are deployed today to instil in children the cultural values and a sense of history. Hence, the paper will also examine some of these narratives, to see how caste is represented in them, and to analyze the implications of such representations in their repeated retellings today It will attempt to show that choice of subject, theme, mode and genre of Children’s Literature all substantially determine the meanings of ’caste’ for the ‘impressionable minds’ they target. Through the detailed analysis, especially of highly popular stories in Baital Pachisi and Singhasan Battisi (both 11th CE), this paper will attempt to reveal how children in India are introduced to the ideas of caste: how, when narrated by the paternal/maternal figure, the child imbibes the ideals of caste along with the other societal norms: how these ideas are juxtaposed by the child onto her social reality, leading to the verification and concretisation of caste ideologies. -

M E H T a C S . X

MEHTA C s .X.) * P ^ . n ) . i q £ h ProQuest Number: 10731380 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731380 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 if£ Political History of Gujarat CAD, JMn 750 - 950 Shobhana Khimjibhai Mehta Thesis submitted for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London. September 1961, CONTENTS page Acknowledgements.... 2 Abstract ... ................. ... ... * * •. ♦ 3 List of Abbreviations.......................... 5 Chapter I. The Sources ....................... 8 Chapter II. Chronology ........ .. ... ... 27 Chapter III. Gujarat at the Decline of the Maitrakas and After ......... 56 Chapter IV. The Saindhavas ... ... ........ 84 Chapter V. The Capas ... .... 106 Chapter VI. The Paramaras ... 135 Chapter VII. The Caulukyas...... ................. 199 Conclusion............... 254 Genealogical Tables ... ... ................... 259 Appendices. (i) The Gurjaras of Broach ... 270 (ii) The Early Cahama^mjLS. ............. 286 Bibliography (i) List of Inscriptions ............ 297 (ii) Primary Sources ........ 307 (iii) Secondary Sources .................. 309 (iv) List of Articles.................... 316 Maps. (a) Gujarat under the Maitraka • ... (b) Gujarat under the Paramaras ........ (c) Gujarat under the Caulukyas ........ (d) India in ca. 977 A.D........... -

On the Yoga of Patanjali and King Bhoja.Pdf

C ON THE YOGA OF PATANJALI AND KING BHOJA Dr. Suryansu Ray According to the Vedas, all living beings, including plants, microbes or developed creatures, are entangled in material bodies from time immemorial. They have been continually migrating from one body to another, the exact form of which depends on their past fruitive actions and the intensity of their desires in their current life. For migrating from one body to another, there are available 8.4 million species on this earth alone. Although the original state of these sparks of life is blissful by default, they falsely suffer relentless agony during their seemingly endless journey through this horrible vortex of transmigration. This false sense of suffering, being experienced by the genuinely happy consciousness, is due to a shroud of ignorance that blinds their faculty of discriminating between what is and what appears. In fact, ignorance is a sure symptom of consciousness entangled in matter. It is produced by their failure to differentiate between matter and consciousness. This gloomy situation is not, however, hopeless for a soul arrested in a body. The Vedas announce the voice of hope that this bondage, although from eternity, is not at all permanent and that there exist several regular systems, which can be followed in a controlled manner with a view to breaking out of the vicious cycle of transmigration. One of these systems is called the yoga as written down by Maharshi Patanjali in the form of sūtras, that is, aphorisms. It has been and is still being practised by yogīs for liberation from their material bondage so that the body is finally cast off. -

The Book Was Drenched

THE BOOK WAS DRENCHED TEXT CROSS WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY TEXT LITE WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY < c W ^ fc ^ B]<OU 168462 5m > Ct nn TI 7 99 i _l J Major His Highness Raj Rajeshwar 5ramad Rajai Hind Maharajadhiraj Sri Sir Umaid Singhji Sahib Bahadur, G.C.I.E., K. C.S.I., K.CV.O., Maharaja of Jodhpur. HISTORY OF^THE RASHTRAKUTAS (RATHODAS) (From the beginning to the migration of Rao Siha ioicards Maricar.) HISTORY OF THE RASHTRAKUTAS. (RATHODAS) From th bcfinninff to the migration of Rao Stha towardi Marwar, BY PANDIT BISHESHWAR NATH REU, Superintendent, AHCH^OLOGICAL DEPARTMENT & SUMER PUBLIC LIBKAKV, JODHPUR. JODHPUR: THE ARCHAEOLOGICAU DEPARTMENT. 1933. Published orders of the Jodhpur Darbar. FIRST EDITION Price Rs. :2'i- Jodhjr.tr: Printed at the Marwar State Press PREFACE. This volume contains the history of the early RSshtrakutas (Rathotfas) and their well-known branch, the Gahatfavalas of Kanauj up to the third-quarter of the 13th century of Vikrama era, that is, up to the migration of Rao Slha towards Marwar. In the absence of any written account of the rulers of this dynasty, the history is based on its copper plates, inscriptions and coins hitherto discovered. Sanskrit, Arabic and English 1 works, which throw some light on the history of this dynasty, however meagre, have also been referred to. Though the material thus gathered is not much, yet what is known is sufficient to prove that some of the kings of this dynasty were most powerful rulers of their time. Further, some of them, besides being the patrons of art and literature, were themselves good scholars. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/05/2021 01:30:17PM Via Free Access at the Crossroads: Śaiva Religious Networks in Uparamāla 49

Chapter 2 At the Crossroads: Śaiva Religious Networks in Uparamāla This chapter represents a crossroads: the midway point in the northwest ex- pansion of the Pāśupata movement as charted in the SP in a region known as Uparamāla. Incorporating areas of what is today northern Madhya Pradesh and southeast Rajasthan, Uparamāla was also a crossroads in the heart of cen- tral India where many of the sub-continental trade routes converged, creat- ing an atmosphere of social diversity and political competition. This region figures prominently in the SP account of Pāśupata origins as home to the city of Ujjain, one of the locales the Pāśupata tradition claimed as its own. As the purāṇa’s authors report, it was in the cremation ground at Ujjain that Lakulīśa commenced with the dissemination of his Pāśupata doctrine, beginning with the initiation of his first pupil, Kauśika. Ujjain was a dynamic center of reli- gious activity, with a particular importance as an early Śaiva center, but mate- rial and epigraphic sources that survive from the period under investigation here are relatively scare. By contrast, the surrounding landscape of Uparamāla is particularly rich in epigraphic and material sources for the study of Śaivism, which have not yet received sufficient scholarly attention. Since Uparamāla was a meeting place for so many different people and communities, the sources from this region record a polyphony of voices— including those of artisans, merchants, women, religious specialists, and kings—that constituted early Śaiva communities in the area. This chapter situates these voices in their particular geographic and social contexts and, through this emplacement, highlights significant differences in the construc- tion and social uses of Śaiva religiosity. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Major dynasties of north India( 647-1200 ce) Module Id I C/ OIH/ 18 Pre-requisites Knowledge in the political history of early medieval India Objectives To know the history of north india from the death of Harshavardhana upto the establishment of Delhi sultanate- Rajput kingdoms Keywords Rajputs/ Pratiharas/ Gahawars/Chandellas/ Chauhans/Paramaras/ Palas/Senas/ Kanauj E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The political unity of Northern India achieved under Harsha was broken after his death. Thereafter, a number of lineages vied for control over Kanauj. Taking advantage of this political confusion, the Rajputs established their kingdoms on the ruins of Harsha’s empire. They became so prominent that the period (647-1192 CE) from the death of Harsha till the Muslim conquest of Northern India in the 12th century is called the Rajput period of Indian history. Even after that many Rajput states continued to survive for a long time. In the period of Muslim aggression, the Rajputs were the main defenders of Hindu religion and Culture. This is very important period in the history of North India, for it witnessed substantial changes in the political, social, economic and religious sectors. We may divide this age, for the sake of convenience into two phases. The first phase starts from 8th century and terminates at 10th century whereas the second phase starts from the 11th century up to the beginning of 13th century CE. The first phase is dominated by the “Age of the three kingdoms”, i.e.