View / Download the Full Paper in a New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

TALES of KING VIKRAM and BETAAL the VAMPIRE Baital

TALES OF KING VIKRAM AND BETAAL THE VAMPIRE The stories of TALES OF KING VIKRAM AND BETAAL THE VAMPIRE is an icon of Indian storey telling, a brain teaser. Although there are 32 stories 25 are covered in Betal Panchisi. I will be sharing with you shortly, some of the stories that are available with me. I am sure, after some time my colleague will definitely let me know the stories which I could not lay hand and help me in endeavoring my efforts. Baital Pancsihi: A very famous account of human and vetal interaction is chronicled in the Baital Pancsihi ('Twenty Five Tales Of The Vampire) which consist of twenty five tales chronicling the adventures of King Vikramaditya and how his wits were pitted against a vetal a sorcerer had asked him to capture for him. Vetals have great wisdom and insight into the human soul in addition to being able to see into the past and future and are thus very valuable acquisitions to wise men. This particular vetal inhabited a tree in a crematorium/graveyard and the only way it could be captured was by standing still and completely silent in the middle of the graveyard/crematorium. However, every single time the king tried this vetal would tempt him with a story that ended in a question the answering of which King Vikramaditya could not resist. As a result the vetal would re-inhabit the tree and the king was left to try again. Only after relating twenty five tales does the vetal allow the king to bear him back to the sorcerer, hence the name Baital Pancsihi. -

The Gupta Empire: an Indian Golden Age the Gupta Empire, Which Ruled

The Gupta Empire: An Indian Golden Age The Gupta Empire, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 320 to 550 AD, ushered in a golden age of Indian civilization. It will forever be remembered as the period during which literature, science, and the arts flourished in India as never before. Beginnings of the Guptas Since the fall of the Mauryan Empire in the second century BC, India had remained divided. For 500 years, India was a patchwork of independent kingdoms. During the late third century, the powerful Gupta family gained control of the local kingship of Magadha (modern-day eastern India and Bengal). The Gupta Empire is generally held to have begun in 320 AD, when Chandragupta I (not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire), the third king of the dynasty, ascended the throne. He soon began conquering neighboring regions. His son, Samudragupta (often called Samudragupta the Great) founded a new capital city, Pataliputra, and began a conquest of the entire subcontinent. Samudragupta conquered most of India, though in the more distant regions he reinstalled local kings in exchange for their loyalty. Samudragupta was also a great patron of the arts. He was a poet and a musician, and he brought great writers, philosophers, and artists to his court. Unlike the Mauryan kings after Ashoka, who were Buddhists, Samudragupta was a devoted worshipper of the Hindu gods. Nonetheless, he did not reject Buddhism, but invited Buddhists to be part of his court and allowed the religion to spread in his realm. Chandragupta II and the Flourishing of Culture Samudragupta was briefly succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta, whose reign was short. -

Ramayana of * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH with EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY

THE Ramayana OF * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH WITH EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY (. ^ ^reenivasa jHv$oiu$ar, B. A., LECTURER S. P G. COLLEGE, TRICHINGj, Balakanda and N MADRAS: * M. K. PEES8, A. L. T. PRKS8 AND GUARDIAN PBE8S. > 1910. % i*t - , JJf Reserved Copyright ftpfiglwtd. 3 [ JB^/to PREFACE The Ramayana of Valmeeki is a most unique work. The Aryans are the oldest race on earth and the most * advanced and the is their first ; Ramayana and grandest epic. The Eddas of Scandinavia, the Niebelungen Lied of Germany, the Iliad of Homer, the Enead of Virgil, the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso of Dante, the Paradise Lost of Milton, the Lusiad of Camcens, the Shah Nama of Firdausi are and no more the Epics ; Ramayana of Valmeeki is an Epic and much more. If any work can clam} to be the Bible of the Hindus, it is the Ramayana of Valmeeki. Professor MacDonell, the latest writer on Samskritha Literature, says : " The Epic contains the following verse foretelling its everlasting fame * As long as moynfain ranges stand And rivers flow upon the earth, So long will this Ramayana Survive upon the lips of men. This prophecy has been perhaps even more abundantly fulfilled than the well-known prediction of Horace. No pro- duct of Sanskrit Literature has enjoyed a greater popularity in India down to the present day than the Ramayana. Its story furnishes the subject of many other Sanskrit poems as well as plays and still delights, from the lips* of reciters, the hearts of the myriads of the Indian people, as at the 11 PREFACE great annual Rama-festival held at Benares. -

Unit 3 the Age of Empires: Guptas and Vardhanas

SPLIT BY - SIS ACADEMY www.tntextbooks.inhttps://t.me/SISACADEMYENGLISHMEDIUM Unit 3 The Age of Empires: Guptas and Vardhanas Learning Objectives • To know the establishment of Gupta dynasty and the empire-building efforts of Gupta rulers • To understand the polity, economy and society under Guptas • To get familiar with the contributions of the Guptas to art, architecture, literature, education, science and technology • To explore the signification of the reign of HarshaVardhana Introduction Sources By the end of the 3rd century, the powerful Archaeological Sources empires established by the Kushanas in the Gold, silver and copper coins issued north and Satavahanas in the south had by Gupta rulers. lost their greatness and strength. After the Allahabad Pillar Inscription of decline of Kushanas and Satavahanas, Samudragupta. Chandragupta carved out a kingdom and The Mehrauli Iron Pillar Inscription. establish his dynastic rule, which lasted Udayagiri Cave Inscription, Mathura for about two hundred years. After the Stone Inscription and Sanchi Stone downfall of the Guptas and thereafter and Inscription of Chandragupta II. interregnum of nearly 50 years, Harsha of Bhitari Pillar Inscription of Vardhana dynasty ruled North India from Skandagupta. 606 to 647 A.D (CE). The Gadhwa Stone Inscription. 112 VI History 3rd Term_English version CHAPTER 03.indd 112 22-11-2018 15:34:06 SPLIT BY - SIS ACADEMY www.tntextbooks.inhttps://t.me/SISACADEMYENGLISHMEDIUM Madubhan Copper Plate Inscription Lichchhavi was an old gana–sanga and Sonpat Copper Plate its territory lay between the Ganges and Nalanda Inscription on clay seal the Nepal Terai. Literary Sources Vishnu, Matsya, Vayu and Bhagavata Samudragupta (c. -

Reconnecting Through Cultural Translations of Time and Motion

The perception of time has shifted for many people due to COVID-19 pandemic. The concept seems paradoxical where time eludes or stagnates even though it is not a material object that we can physically grasp, and yet, we commonly say Finding Rhythm Amidst Disruption: that ‘time is slipping past our fingers.’ Additionally, this pandemic has brought challenges with an unexpected translation of time: how soon or late our town Reconnecting through Cultural is infected, how many days we haven’t seen a friend, or how many minutes we have “zoom”ed throughout the day. While the context and consequences are Translations of Time and Motion radically different, we refer to this analogy to discuss the diverse translations and cultural shifts of time. Living in the United States as bicultural individuals —Indian, Iranian, Thai— Ladan Bahmani we perceive time in conjunction with an additional calendrical system and time Illinois State University, United States difference. Archana Shekara is a first-generation Indian American who has been in the United States for three decades and considers it her second home. Archana Shekara Ladan Bahmani is a first-generation Iranian American. She immigrated to Illinois State University, United States United States from Iran and has lived in the country for over a decade. Annie Sungkajun is a second-generation American, whose parents immigrated to the Annie Sungkajun United States from Thailand. When she began her college education, her family Illinois State University, United States moved back to Thailand. We have become conscious of time and its shift as we constantly compare and move between different calendrical systems. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5022

12 NAGARi ALPHABET, SIGNS AND SYMBOLS OF PARAMARA INSCRIPTIONS Arvind K. Singh The Paramaras, started their political career the scribe and the engraver was performed by the in the ninth century C.E. as feudatories of the same person. The relevant epigraphic data provide 1 imperial Racmrak0[)'ls1monarch , succeeded in significant details concerning these professionals, 1 building a strong kingdom in the heart of the central and sometimes mention their predecessors as well , India in the tenth century and played a leading as native place, role, occupation and designation j role in the history of the country till fourteenth as applied to poets, scribes and engravers. It is century C.E. During the course of their political obvious from the examples of good epigraphic I' existence, the Paramaras ruled over various poetry that high talented poets were employed for territories, which includes Maiava proper as well composing the inscriptions. The poets were 1 the adjacent districts of Vidisha in the east, Ratlam honored by different ways, even by donating land. in the west, Indore and the parts of Hoshangabad AtrO stone inscription of the time of JayasiAha: in the south-east. In addition the imperial royal V.S. 1314 (C.E. 1258) records the donation by house of Maiava, there was other contemporary JayasiAhadeva of the village Mhaisada (Bhainra) royal houses of the Paramaras over Arbuda in the territorial division of PaAvimha in favor of a manda, Maru-mandala, Jalor, and Vaga. The kavicakravartin, mhakkura NarayaGa (no. 55). house that grew to power in the region around · Tilakwada copper-plate inscription of the time of Arbuda-maandala or Mount Abo, subsequently Bhojadeva: V.S. -

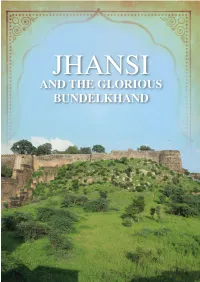

Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through the Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857?

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through The Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857? Attractions in and around Jhansi Jhansi Fort Rani Mahal Ganesh Mandir Mahalakshmi Temple Gangadharrao Chhatri Star Fort Jokhan Bagh St Jude’s Shrine Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery Jhansi Railway Station Orchha I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi is one of the most vibrant cities of Uttar Pradesh today. But the city is also steeped in history. The city of Rani Laxmibai - the brave queen who led her forces against the British in 1857 and the region around it, are dotted with monuments that go back more than 1500 years! While thousands of tourists visit Jhansi each year, many miss the layered past of the city. In fact, few who visit the famous Jhansi Fort each year, even know that it is in its historic Ganesh Mandir that Rani Laxmibai got married. Or that there is also a ‘second’ Fort hidden within the Jhansi cantonment, where the revolt of 1857 first began in the city. G L I M P S E S O F J H A N S I ’ S H I S T O R Y JHANSI THROUGH THE AGES Jhansi, the historic town and major tourist draw in Uttar Pradesh, is known today largely because of its famous 19th-century Queen, Rani Laxmibai, and the fearless role she played during the Revolt of 1857. There are also numerous monuments that dot Jhansi, remnants of the Bundelas and Marathas that ruled here from the 17th to the 19th centuries. -

New Kings and Kingdoms

History - Chapter 2 New Kings and Kingdoms Medieval Period Early Medieval Later Medieval Period 8th Period-12th Century to 12th Century to 18th Century Century Who were the new powers? How they became powerful? The Emergence of New Dynasties ● Rich landlords or warrior chiefs became subordinates of kings and were given title of samantas, and were expected to bring gifts for their kings or overlords, had to be present at their courts and would provide them military support. With more power and wealth, samantas became ‘maha-samanta’ or ‘mahamandaleshwar’, and some of them became free from their overlords. ● Dantidurga, who was a Rashtrakuta chief, performed ‘hiranyagarbha’ ritual to become a Kshatriya and then he overthrew his Chalukya overlord. ● In spite of being Brahmans, Kadamba Mayurasharman and Gurjara-Pratihara Harichandra built their kingdoms in Karnataka and Rajasthan. Prashastis and Land Grants ● Prashastis are a special kind of inscription, meaning “in praise of”. They were composed by learned Brahmanas in praise of the rulers, which may not be literally true; but, they tell us how rulers of that time wanted to illustrate themselves. ● If the kings liked the prashastis, they gave land as a gift to the Brahmans, with records of it on copper plates. ● Kalhana was a famous writer who wrote a long Sanskrit poem (Rajatarangini - "The River of Kings") on kings of Kashmir by using a variety of sources,such as inscriptions, documents, eyewitness accounts, and earlier histories. He was usually critical about rulers and their policies. Rajput ancestry can be divided between Suryavanshi (“House of the Sun,” or Solar people), or those descended from Rama, the hero of the epic Ramayana; and Chandravanshi (“House of the Moon,” or Lunar people), or those descended from Krishna, the hero of the epic Mahabharata. -

VEDA (Level-A)

Ekatmata Stotra - Song of Unity CLASS-III 9 Notes EKATMATA STOTRA - SONG OF UNITY A nation is consisting of its people, physical features, cultures and values inherited in the society. The culture and values are developed, grown and transmitted from one area to another over a period of time. These values, special natural phenomena, noble action of its people and leaders becomes motivation for next generation. Ekatm Stotra is collection of shlokas praising the nature, mountains, rivers, great leaders and the values of Indian society. This lesson will make you feel proud about our country. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to : • recite all 33 shlokas from ekatmata stotra; • identify the grand traditions of the land; • appreciate the beauty of nature and its interaction with people; and • appreciate the rich literature of country. OBE-Bharatiya Jnana Parampara 77 Ekatmata Stotra - Song of Unity CLASS-III 9.1 SHLOKA OF EKATMATA STOTRA (1 TO 20) Notes Are you not proud of you? Your parents? People? Nation? Country and the society? We as a nation, have a great things to remember. We study the historical events in social studies. Here is a set of shlokas containing all such grand scenario of our nation. This is called Ekatmata Stotra. The song of unity. All the Sadhakas, Sadhana and tradition is just listed here. 1- Å lfPpnkuan:ik; ueksLrq ijekReusA T;ksfreZ;Lo:ik; foÜoekaxY;ewrZ;sAA1AA Om. I bow to the supreme Lord who is the very embodiment of Truth, Knowledge and Happiness, the one who is enlightened, and who is the very incarnate of universal good. -

Asiatische Studien Etudes Asiatiques L U I • 1998

Schweizerische Asiengesellschaft Société Suisse-Asie 5 Asiatische Studien Etudes Asiatiques LUI • 1998 Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft Revue de la Société Suisse - Asie Peter Lang Bern • Berlin • Frankfurtam Main • New York • Paris • Wien ASIATISCHE STUDIEN ÉTUDES ASIATIQUES Herausgegeben von / Editées par JOHANNES BRONKHORST (Lausanne) - REINHARD SCHULZE (Bern) - ROBERT GASSMANN (Zürich) - EDUARD KLOPFENSTEIN (Zürich) - JACQUES MAY (Lausanne) - GREGOR SCHOELER (Basel) Redaktion: Ostasiatisches Seminar der Universität Zürich, Zürichbergstrasse 4, CH-8032 Zürich Die Asiatischen Studien erscheinen vier Mal pro Jahr. Redaktionstermin für Heft 1 ist der 15. September des Vorjahres, für Heft 2 der 15. Dezember, für Heft 3 der 15. März des gleichen Jahres und für Heft 4 der 15. Juni. Manuskripte sollten mit doppeltem Zeilenabstand geschrieben sein und im allgemeinen nicht mehr als vierzig Seiten umfassen. Anmerkungen, ebenfalls mit doppeltem Zeilenabstand geschrieben, und Glossar sind am Ende des Manuskriptes beizufügen (keine Fremdschriften in Text und Anmerkungen). Les Études Asiatiques paraissent quatre fois par an. Le délai rédactionnel pour le nu méro 1 est au 15 septembre de l’année précédente, pour le numéro 2 le 15 décembre, pour le numéro 3 le 15 mars de la même année et pour le numéro 4 le 15 juin. Les manuscrits doivent être dactylographiés en double interligne et ne pas excéder 40 pages. Les notes, en numérotation continue, également dactylographiées en double interligne, ainsi que le glossaire sont présentés à la fin du manuscrit. The Asiatische Studien are published four times a year. Manuscripts for publication in the first issue should be submitted by September 15 of the preceding year, for the second issue by December 15, for the third issue by March 15 and for the fourth issue by June 15.