Win Women Warrior Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for Women Existence in Popular Espionage Movies Salt (2010) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

Benita Amalina — Fighting For Women Existence in Popular Espionage Movies Salt (2010) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012) FIGHTING FOR WOMEN EXISTENCE IN POPULAR ESPIONAGE MOVIES SALT (2010) AND ZERO DARK THIRTY (2012) Benita Amalina [email protected] Abstract American spy movies have been considered one of the most profitable genre in Hollywood. These spy movies frequently create an assumption that this genre is exclusively masculine, as women have been made oblivious and restricted to either supporting roles or non-spy roles. In 2010 and 2012, portrayal of women in spy movies was finally changed after the release of Salt and Zero Dark Thirty, in which women became the leading spy protagonists. Through the post-nationalist American Studies perspective, this study discusses the importance of both movies in reinventing women’s identity representation in a masculine genre in response to the evolving American society. Keywords: American women, hegemony, representation, Hollywood, movies, popular culture Introduction The financial success and continuous power of this industry implies that there has been The American movie industry, often called good relations between the producers and and widely known as Hollywood, is one of the main target audience. The producers the most powerful cinematic industries in have been able to feed the audience with the world. In the more recent data, from all products that are suitable to their taste. Seen the movies released in 2012 Hollywood from the movies’ financial revenues as achieved $ 10 billion revenue in North previously mentioned, action movies are America alone, while grossing more than $ proven to yield more revenue thus become 34,7 billion worldwide (Kay, 2013). -

ZERO DARK THIRTY an Original Screenplay by Mark Boal October 3

ZERO DARK THIRTY An Original Screenplay by Mark Boal October 3, 2011 all rights reserved FROM BLACK, VOICES EMERGE-- We hear the actual recorded emergency calls made by World Trade Center office workers to police and fire departments after the planes struck on 9/11, just before the buildings collapsed. TITLE OVER: SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 We listen to fragments from a number of these calls...starting with pleas for help, building to a panic, ending with the caller's grim acceptance that help will not arrive, that the situation is hopeless, that they are about to die. CUT TO: TITLE OVER: TWO YEARS LATER INT. BLACK SITE - INTERROGATION ROOM DANIEL I own you, Ammar. You belong to me. Look at me. This is DANIEL STANTON, the CIA's man in Islamabad - a big American, late 30's, with a long, anarchical beard snaking down to his tattooed neck. He looks like a paramilitary hipster, a punk rocker with a Glock. DANIEL (CONT'D) (explaining the rules) If you don't look at me when I talk to you, I hurt you. If you step off this mat, I hurt you. If you lie to me, I'm gonna hurt you. Now, Look at me. His prisoner, AMMAR, stands on a decaying gym mat, surrounded by four GUARDS whose faces are covered in ski masks. Ammar looks down. Instantly: the guards rush Ammar, punching and kicking. DANIEL (CONT'D) Look at me, Ammar. Notably, one of the GUARDS wearing a ski mask does not take part in the beating. 2. EXT. -

Zero Dark Thirty Error

Issue 7 | Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism | 23 troop carrier with no clear sense of destination, speaks again understated performances further serve to create what might as much to a national as a personal loss of purpose, afer the be described as a reality afect. quest is over. Te 9/11 sequence ofers an extreme version of the real- Te flm’s epilogue has received considerable critical atten- ist aesthetic and the rejection of spectacle. From the second tion1; the prologue less so. And where critics do mention it, plane hitting the tower, to the falling man, to the rubble details are ofen misremembered. In an interview with Kyle of ground zero, there are any number of iconic images the Buchanan, screenwriter Mark Boal refects on the difculties flmmakers might have selected to represent the destruction of writing the ‘opening scene’ of Zero Dark Tirty (2013). Te wrought by the attacks. However, what such images have in scene he is referring to in this discussion, however, is the infa- common, what potentially makes them efective as a form of mous torture scene that begins the narrative proper (to which cultural shorthand, also renders them problematic in terms I will return). It is as if he has momentarily forgotten the scene of eliciting a fresh response – and certainly in terms of the Intimacy, ‘truth’ and the gaze: that precedes it in the original shooting script as well as the slow-burn, reality afect. Teir very familiarity can render flm. Given this oversight by the writer himself, it is under- such images hackneyed and over-determined. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 1 (2018) The American Woman Warrior: A Transnational Feminist Look at War, Imperialism, and Gender Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet ABSTRACT: This article examines the issue of torture and spectatorship in the film Zero Dark Thirty through the question of how it deploys gender ideologically and rhetorically to mediate and frame the violence it represents. It begins with the controversy the film provoked but focuses specifically on the movie’s representational and aesthetic techniques, especially its self-awareness about being a film about watching torture, and how it positions its audience in relation to these scenes. Issues of spectator identification, sympathy, interpellation, affect (for example, shame) and genre are explored. The fact that the main protagonist of the film is a woman is a key dimension of the cultural work of the film. I argue that the use of a female protagonist in this film is part of a larger trend in which the discourse of feminism is appropriated for politically conservative and antifeminist ends, here the tacit justification of the legally murky world of black sites and ‘enhanced interrogation techniques.’ KEYWORDS: gender; women’s studies; torture; war on terror; Abu Ghraib; spectatorship; neoliberalism; Angela McRobbie; Some of you will recognize my title as alluding to Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior (1975), a fictionalized autobiography in which she evokes the fifth-century Chinese legend of a girl who disguises herself as a man in order to go to war in the place of her frail old father. Kingston’s use of this legend is credited with having popularized the story in the United States and paved the way for the 1998 Disney adaptation. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

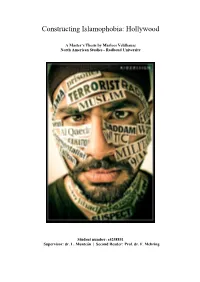

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood A Master’s Thesis by Marloes Veldhausz North American Studies - Radboud University Student number: s4258851 Supervisor: dr. L. Munteán | Second Reader: Prof. dr. F. Mehring Veldhausz 4258851/2 Abstract Islam has become highly politicized post-9/11, the Islamophobia that has followed has been spread throughout the news media and Hollywood in particular. By using theories based on stereotypes, Othering, and Orientalism and a methodology based on film studies, in particular mise-en-scène, the way in which Islamophobia has been constructed in three case studies has been examined. These case studies are the following three Hollywood movies: The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and American Sniper. Derogatory rhetoric and mise-en-scène aspects proved to be shaping Islamophobia. The movies focus on events that happened post- 9/11 and the ideological markers that trigger Islamophobia in these movies are thus related to the opinions on Islam that have become widespread throughout Hollywood and the media since; examples being that Muslims are non-compatible with Western societies, savages, evil, and terrorists. Keywords: Islam, Muslim, Arab, Islamophobia, Religion, Mass Media, Movies, Hollywood, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniper, Mise-en-scène, Film Studies, American Studies. 2 Veldhausz 4258851/3 To my grandparents, I can never thank you enough for introducing me to Harry Potter and thus bringing magic into my life. 3 Veldhausz 4258851/4 Acknowledgements Thank you, first and foremost, to dr. László Munteán, for guiding me throughout the process of writing the largest piece of research I have ever written. I would not have been able to complete this daunting task without your help, ideas, patience, and guidance. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-2 | 2017 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Lennart Soberon, ““The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 12, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ejas/12086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl... 1 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon 1 While recent years have seen no shortage of American action thrillers dealing with the War on Terror—Act of Valor (2012), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Lone Survivor (2013) to name just a few examples—no film has been met with such a great controversy as well as commercial success as American Sniper (2014). Directed by Clint Eastwood and based on the autobiography of the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, American Sniper follows infamous Navy Seal Chris Kyle throughout his four tours of duty to Iraq. -

Unclassified Fictions: the CIA, Secrecy Law, and the Dangerous Rhetoric of Authenticity

Unclassified Fictions: The CIA, Secrecy Law, and the Dangerous Rhetoric of Authenticity Matthew H. Birkhold* ABSTRACT Zero Dark Thirty , Kathryn Bigelow’s cinematic account of the manhunt for Osama bin Laden, attracted tremendous popular attention, inspiring impassioned debates about torture, political access, and responsible filmmaking. But, in the aftermath of the 2013 Academy Awards, critical scrutiny of the film has abated and the Senate has dropped its much-hyped inquiry. If the discussion about Zero Dark Thirty ultimately proved fleeting, our attention to the circumstances of its creation should not. The CIA has a longstanding policy of promoting the accuracy of television shows and films that portray the agency, and Langley’s collaboration with Bigelow provided no exception. To date, legal scholarship has largely ignored the CIA’s policy, yet the practice of assisting filmmakers has important consequences for national security law. Recently, the CIA’s role in Zero Dark Thirty’s creation and the agency’s refusal to release authentic images of the deceased Osama bin Laden reveals its attitude toward fiction and how it impacts the CIA’s legal justifications for secrecy. By conducting a close analysis of CIA affidavits submitted in FOIA litigation and recently declassified records detailing the CIA’s interactions with Bigelow, this article demonstrates how films like Zero Dark Thirty function as workarounds where the underlying records are classified. These films are “unclassified fictions” in that they allow the CIA to preserve the secrecy of classified records by communicating nearly identical information to the public. Unclassified fictions, in other words, allow the CIA to evade secrecy while maintaining that secrecy—to speak without speaking. -

Movie Titles List, Genre

ALLEGHENY COLLEGE GAME ROOM MOVIE LIST SORTED BY GENRE As of December 2020 TITLE TYPE GENRE ACTION 300 DVD Action 12 Years a Slave DVD Action 2 Guns DVD Action 21 Jump Street DVD Action 28 Days Later DVD Action 3 Days to Kill DVD Action Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter DVD Action Accountant, The DVD Action Act of Valor DVD Action Aliens DVD Action Allegiant (The Divergent Series) DVD Action Allied DVD Action American Made DVD Action Apocalypse Now Redux DVD Action Army Of Darkness DVD Action Avatar DVD Action Avengers, The DVD Action Avengers, End Game DVD Action Aviator DVD Action Back To The Future I DVD Action Bad Boys DVD Action Bad Boys II DVD Action Batman Begins DVD Action Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice DVD Action Black Hawk Down DVD Action Black Panther DVD Action Blood Father DVD Action Body of Lies DVD Action Boondock Saints DVD Action Bourne Identity, The DVD Action Bourne Legacy, The DVD Action Bourne Supremacy, The DVD Action Bourne Ultimatum, The DVD Action Braveheart DVD Action Brooklyn's Finest DVD Action Captain America: Civil War DVD Action Captain America: The First Avenger DVD Action Casino Royale DVD Action Catwoman DVD Action Central Intelligence DVD Action Commuter, The DVD Action Dark Knight Rises, The DVD Action Dark Knight, The DVD Action Day After Tomorrow, The DVD Action Deadpool DVD Action Die Hard DVD Action District 9 DVD Action Divergent DVD Action Doctor Strange (Marvel) DVD Action Dragon Blade DVD Action Elysium DVD Action Ender's Game DVD Action Equalizer DVD Action Equalizer 2, The DVD Action Eragon -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10.