Chapter 2 of Cetaceans and Ships; Or, the Moorings of Our Being

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More!

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More! Grade Level: 3rd -5 th Objectives: Students will construct their own meaning from a variety of legends and myths about dolphins and then create their own dolphin legend or myth. Florida Sunshine State Standards: Language Arts LA.A.2.2.5 The student reads and organizes information for a variety of purposes, including making a report, conducting interviews, taking a test, and performing an authentic task. LA.B.1.2 The student uses the writing processes effectively. Social Studies SS.A.1.2.1: The student understands how individuals, ideas, decisions, and events can influence history. SS.B.2.2.4: The student understands how factors such as population growth, human migration, improved methods of transportation and communication, and economic development affect the use and conservation of natural resources. Science SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. National Science Education Standards: Content Standard C (K-4) - Characteristics of Organisms : Each plant or animal has different structures that serve different functions in growth, survival, and reproduction. For example, humans have distinct body structures for walking, holding, seeing, and talking. Content Standard C (5-8) - Diversity and adaptations of Organisms : Biological evolution accounts for the diversity of species developed through gradual processes over many generations. Species acquire many of their unique characteristics through biological adaptation, which involves the selection of naturally occurring variations in populations. Biological adaptations include changes in structures, behaviors, or physiology that enhance survival and reproductive success in a particular environment. -

Andy Clark, ‘Whatever Next?’

BBS Commentary on: Andy Clark, ‘Whatever Next?’ Word Counts Abstract: 61 Main text: 994 References: 69 Entire text: 1,180 Commentary Title Perception vs Action: The Computations May Be The Same But The Direction Of Fit Differs Author Information Nicholas Shea Faculty of Philosophy University of Oxford 10 Merton Street Oxford OX1 4JJ UK tel. 01865 286896 [email protected] www.philosophy.ox.ac.uk/members/nicholas_shea Abstract Although predictive coding may offer a computational principle that unifies perception and action, states with different directions of fit are involved (with indicative and imperative contents, respectively). Predictive states are adjusted to fit the world in the course of perception, but in the case of action the corresponding states act as a fixed target towards which the agent adjusts the world. Main Text One of the central insights motivating Clark’s interest in the potential for predictive coding to provide a unifying computational principle is the fact that it can be the basis of effective algorithms in both the perceptual and motor domains (Eliasmith 2007, 380). That is surprising because perceptual inference in natural settings is based on a rich series of sensory inputs at all times, whereas a natural motor control task only specifies a final outcome. Many variations in the trajectory are irrelevant to achieving the final goal (Todorov and Jordan 2002), a redundancy that is absent from the perceptual inference problem. Despite this disanalogy, the two tasks are instances of the same general mathematical problem (Todorov 2006). Clark emphasises the “deep unity” between the two problems, which is justified but might serve to obscure an important difference. -

The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

More Fun Than Fun: The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021 An iconic photo of Konrad Lorenz with his favourite geese. Photo: Willamette Biology, CC BY-SA 2.0 This article is part of the ‘More Fun Than Fun‘ column by Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar. He will explore interesting research papers or books and, while placing them in context, make them accessible to a wide readership. RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR Among the books I read as a teenager, two completely changed my life. One was The Double Helix by Nobel laureate James D. Watson. This book was inspiring at many levels and instantly got me addicted to molecular biology. The other was King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, soon to be a Nobel laureate. The study of animal behaviour so charmingly and unforgettably described by Lorenz kindled in me an eternal love for the subject. The circumstances in which I read these two books are etched in my mind and may have partly contributed to my enthusiasm for them and their subjects. The Double Helix was first published in London in 1968 when I was a pre-university student (equivalent to 11th grade) at St Joseph’s college in Bangalore and was planning to apply for the prestigious National Science Talent Search Scholarship. By then, I had heard of the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA and its profound implications. I was also tickled that this momentous discovery was made in 1953, the year of my birth. I saw the announcement of Watson’s book on the notice board in the British Council Library, one of my frequent haunts. -

National Bulletin Volume 30 No

American Association of Teachers of French NATIONAL BULLETIN VOLUME 30 NO. 1 SEPTEMBER 2004 FROM THE PRESIDENT butions in making this an exemplary con- utility, Vice-President Robert “Tennessee ference. Whether you were in attendance Bob” Peckham has begun to develop a Web physically or vicariously, you can be proud site in response to SOS calls this spring of how our association represented all of and summer from members in New York us and presented American teachers of state, and these serve as models for our French as welcoming hosts to a world of national campaign to reach every state. T- French teachers. Bob is asking each chapter to identify to the Regional Representative an advocacy re- Advocacy, Recruitment, and Leadership source person to work on this project (see Development page 5), since every French program is sup- Before the inaugural session of the con- ported or lost at the local level (see pages 5 ference took center stage, AATF Executive and 7). Council members met to discuss future A second initiative, recruitment of new initiatives of our organization as we strive to members, is linked to a mentoring program respond effectively to the challenges facing to provide support for French teachers, new Atlanta, Host to the Francophone World our profession. We recognize that as teach- teachers, solitary teachers, or teachers ers, we must be as resourceful outside of We were 1100 participants with speak- looking to collaborate. It has been recog- the classroom as we are in the classroom. nized that mentoring is essential if teach- ers representing 118 nations, united in our We want our students to become more pro- passion for the French language in its di- ers are to feel successful and remain in the ficient in the use of French and more knowl- profession. -

Cognitive Adaptations of Social Bonding in Birds Nathan J

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2007) 362, 489–505 doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1991 Published online 24 January 2007 Cognitive adaptations of social bonding in birds Nathan J. Emery1,*, Amanda M. Seed2, Auguste M. P. von Bayern1 and Nicola S. Clayton2 1Sub-department of Animal Behaviour, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 8AA, UK 2Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EB, UK The ‘social intelligence hypothesis’ was originally conceived to explain how primates may have evolved their superior intellect and large brains when compared with other animals. Although some birds such as corvids may be intellectually comparable to apes, the same relationship between sociality and brain size seen in primates has not been found for birds, possibly suggesting a role for other non-social factors. But bird sociality is different from primate sociality. Most monkeys and apes form stable groups, whereas most birds are monogamous, and only form large flocks outside of the breeding season. Some birds form lifelong pair bonds and these species tend to have the largest brains relative to body size. Some of these species are known for their intellectual abilities (e.g. corvids and parrots), while others are not (e.g. geese and albatrosses). Although socio-ecological factors may explain some of the differences in brain size and intelligence between corvids/parrots and geese/albatrosses, we predict that the type and quality of the bonded relationship is also critical. Indeed, we present empirical evidence that rook and jackdaw partnerships resemble primate and dolphin alliances. Although social interactions within a pair may seem simple on the surface, we argue that cognition may play an important role in the maintenance of long-term relationships, something we name as ‘relationship intelligence’. -

Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: a Case of Convergent Evolution? Amanda Seed*, Nathan Emery & Nicola Claytonà

Ethology CURRENT ISSUES – PERSPECTIVES AND REVIEWS Intelligence in Corvids and Apes: A Case of Convergent Evolution? Amanda Seed*, Nathan Emery & Nicola Claytonà * Department of Psychology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany School of Biological & Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK à Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Invited Review) Correspondence Abstract Nicola Clayton, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Downing Intelligence is suggested to have evolved in primates in response to com- Street, Cambridge CB23EB, UK. plexities in the environment faced by their ancestors. Corvids, a large- E-mail: [email protected] brained group of birds, have been suggested to have undergone a con- vergent evolution of intelligence [Emery & Clayton (2004) Science, Vol. Received: November 13, 2008 306, pp. 1903–1907]. Here we review evidence for the proposal from Initial acceptance: December 26, 2008 both ultimate and proximate perspectives. While we show that many of Final acceptance: February 15, 2009 (M. Taborsky) the proposed hypotheses for the evolutionary origin of great ape intelli- gence also apply to corvids, further study is needed to reveal the selec- doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2009.01644.x tive pressures that resulted in the evolution of intelligent behaviour in both corvids and apes. For comparative proximate analyses we empha- size the need to be explicit about the level of analysis to reveal the type of convergence that has taken place. Although there is evidence that corvids and apes solve social and physical problems with similar speed and flexibility, there is a great deal more to be learned about the repre- sentations and algorithms underpinning these computations in both groups. -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

Les Entreprises Multinationales Au Bas De La Pyramide Économique: Un Cadre D’Analyse Des Stratégies François Perrot

Les entreprises multinationales au bas de la pyramide économique: un cadre d’analyse des stratégies François Perrot To cite this version: François Perrot. Les entreprises multinationales au bas de la pyramide économique: un cadre d’analyse des stratégies. Economies et finances. Ecole Polytechnique X, 2011. Français. pastel-00643949 HAL Id: pastel-00643949 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/pastel-00643949 Submitted on 23 Nov 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE Pour l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Ecole Polytechnique Spécialité: Economie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par François Perrot le 23 Septembre 2011 MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS AT THE BASE OF THE ECONOMIC PYRAMID : A STRATEGIC ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK LES ENTREPRISES MULTINATIONALES AU BAS DE LA PYRAMIDE ECONOMIQUE : UN CADRE D’ANALYSE DES STRATEGIES Directeurs de thèse : Patricia Crifo et Jean-Pierre Ponssard Membres du jury Patricia Crifo Professeur, Université Paris-Ouest & Ecole Polytechnique Jean Desazars de Montgailhard Directeur Général Adjoint, Lafarge Minna Halme Professeur, Aalto University, rapporteur Jean-Pierre Ponssard Professeur, Ecole Polytechnique Shyama Ramani Professeur, United Nations University MERIT & Maastricht University, président Bernard Sinclair-Desgagné Professeur, HEC Montréal & CIRANO, rapporteur 2 L'Ecole Polytechnique n’entend donner aucune approbation, ni improbation, aux opinions émises dans les thèses. -

Trainer to Propose [Seal Corps* As Adjunct to National Defense

Trainer To Propose [Seal Corps* As Adjunct To National Defense By JAMES A. MOORE lng their underwater progress District Correspondent pretty hard going. are weaned, which is about two expert will be one of the princi weeks after birth. It takes spe u That’s only part of the story. pal speakers at the night wind ' ROCKPORT-A “Seal Corps' cial water tanks to transport up, along with Dr. Andreas — the aquatic "equivalent to the Goodridge says seals have an un dolphins from place to place, K-9 (Dog) Corps,” is being canny knack of awareness Rechnitzer, president of the ad but seals can ride ip the back joint World Diving Federation; proposed by the trainer of of any diver in the water up to seat of a car. Rockport's famous honorary as much as four miles away, I Dr. George Bond, captain of Sea harbormaster—Andre the seal Andre having proven this point SEA LIONS “sound off” rau labs One, Two and Three; Ed Harry Goodridge, who runs a time and again. cously for no particular rea win Link, Robert Stenuit and tree expert business, but who While dolphins and “sea son and often nip their •Jon Lindbergh; and Stanton is an outstanding scuba diver, lions” (the circus variety of trainers, while harbor seals Waterman, underwater film said Tuesday he will discuss his “trained seal”) have be e n are quiet, and seem really fond maker who a few years ago idea of using seals in defense taught limited tricks, they have of human company, Goodridge made a movie of Andre in work at the world-famous Boa- faults which Andre's ancestry says. -

Sizing Ocean Giants: Patterns of Intraspecific Size Variation in Marine Megafauna

Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna Craig R. McClain1,2 , Meghan A. Balk3, Mark C. Benfield4, Trevor A. Branch5, Catherine Chen2, James Cosgrove6, Alistair D.M. Dove7, Lindsay C. Gaskins2, Rebecca R. Helm8, Frederick G. Hochberg9, Frank B. Lee2, Andrea Marshall10, Steven E. McMurray11, Caroline Schanche2, Shane N. Stone2 and Andrew D. Thaler12 1 National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, NC, USA 2 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA 3 Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA 4 Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA 5 School of Aquatic & Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 6 Natural History Section, Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada 7 Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta, GA, USA 8 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA 9 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara, CA, USA 10 Marine Megafauna Foundation, Truckee, CA, USA 11 Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wilmington, NC, USA 12 Blackbeard Biologic: Science and Environmental Advisors, Vallejo, CA, USA ABSTRACT What are the greatest sizes that the largest marine megafauna obtain? This is a simple question with a diYcult and complex answer. Many of the largest-sized species occur in the world’s oceans. For many of these, rarity, remoteness, and quite simply the logistics of measuring these giants has made obtaining accurate size measurements diYcult. Inaccurate reports of maximum sizes run rampant through the scientific Submitted 3 October 2014 literature and popular media. -

Post-GWAS Investigations for Discovering Pleiotropic Gene Effects in Cardiovascular Diseases Alex-Ander Aldasoro

Post-GWAS Investigations for discovering pleiotropic gene effects in cardiovascular diseases Alex-Ander Aldasoro To cite this version: Alex-Ander Aldasoro. Post-GWAS Investigations for discovering pleiotropic gene effects in cardio- vascular diseases. Human health and pathology. Université de Lorraine, 2017. English. NNT : 2017LORR0247. tel-01868508 HAL Id: tel-01868508 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01868508 Submitted on 5 Sep 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. AVERTISSEMENT Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la communauté universitaire élargie. Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci implique une obligation de citation et de référencement lors de l’utilisation de ce document. D'autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite encourt une poursuite pénale. Contact : [email protected] LIENS Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4 Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10 http://www.cfcopies.com/V2/leg/leg_droi.php http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/infos-pratiques/droits/protection.htm Ecole Doctorale BioSE (Biologie- Santé- Environnement) Thèse Présentée et soutenue publiquement pour l’obtention du titre de DOCTEUR DE l’UNIVERSITE DE LORRAINE Mention: « Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé » Par: Alex-Ander Aldasoro Post-GWAS Investigations for discovering pleiotropic gene effects in cardiovascular diseases Le 19 Décembre 2017 Membres du jury: Rapporteurs: Mme. -

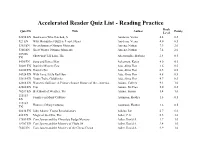

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A.