Capturing Value and Preserving Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 303 318 Author Title Institution Report No Pub

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 318 SE 050 265 AUTHOR Druger, Marvin, Ed. TITLE Science for the Fun of It. A Guide to Informal Science Education. INSTITUTION National Science Teachers Association, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87355-074-9 PUB DATE 88 NOTE 137p.; Photographs may not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROMNational Science Teachers Association, 1742 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20009 ($15.00, 10% discount on 10 or more). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) -- Books (010) -- Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Educational Facilities; Educational Innovation; Educational Media; Educational Opportunities; Educational Television; *Elementary School Science; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mass Media; *Museums; *Nonformal Education; Periodicals; Program Descriptions; Science Education; *Secondary School Science; *Zoos ABSTRACT School provides only a small part of a child's total education. This book focuses on science learning outside of the classroom. It consists of a collection of articles written by people who are involved with sevaral types of informal science education. The value of informal science education extends beyond the mere acquisition of knowledge. Attitudes toward science can be greatly influenced by science experiences outside of the classroom. The intent of this book is to highlight some of the many out-of-school opportunities which exist including zoos, museums, television, magazines and books, and a variety of creative programs and projects. The 19 articles in this volume are organized into four major sections entitled: (1) "Strategies"; (2) "The Media"; (3) "Museums and Zoos"; and (4) "Projects, Coop2titions, and Family Activities." A bibliography of 32 references on these topies is included. -

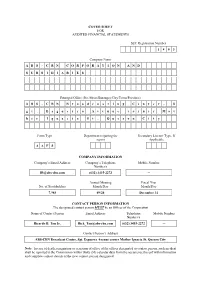

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

Of Pemns Who Use an Emergency Food Program

Characteristics and SelCPerceived Need~of Pemns Who Use an Emergency Food Program BY Pemy L-Lang A Thesis Submitted to the Facuity of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education Faculty of Education University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Acquisitions and Acquisitrons et Bibliogmphii Services senrices bbliographque~ The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronk formais. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retaias ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othdse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. COPYRIGHT PERMISSION A ThmracOmlabmittcd to tbe Fa- ofGduate Studies ofthe Uaivemîty of Manitoba in partir1foinnment ofthe tcqoinments for the degret of Permission buben gnattd to the WBRARY OF TEE UNIVERSïTY OF MANïTOBA to lend or seIl copies of tbis thesWprrctScam, to the NATIONAL LfBRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this tb~Wpracticumand to tend or scU copies of the film, and to UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS INC. to pubiisb an rbstract of tbir thesis/pncticum.. This reproduction or copy of thir thcris buben made avrilable by autbority of the copyright ometsolely for the purpose of private study and resarcb, and may only be reproduceâ and copiai as permitteâ by copyright Lam or witb cxprrss written autborintion fmm the copyright 0WIIer. -

Ar-2004 Pdf Comp

abs-cbn annual report 2004 1 2 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 3 4 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbnabs-cbn annual annual report report 2004 2004 55 6 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 7 8 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 9 10 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 11 12 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 13 14 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 15 16 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbn annual report 2004 17 18 abs-cbn annual report 2004 abs-cbnabs-cbn annual annual report report 2004 20041919 ABS-CBN BROADCASTING CORPORATION AND SUBSIDIARIES BALANCE SHEETS (Amounts in Thousands) Parent Company Consolidated December 31 2003 2003 (As restated - (As restated - 2004 Note 2) 2004 Note 2) ASSETS Current Assets Cash and cash equivalents (Note 4) $356,772 $803,202 $1,291,557 $1,580,355 Receivables - net (Notes 5, 7 and 12) 2,181,412 2,338,136 3,757,824 3,789,278 Current portion of program rights (Note 9) 490,685 566,992 872,983 880,975 Other current assets - net (Note 6) 296,182 193,317 629,426 508,681 Total Current Assets 3,325,051 3,901,647 6,551,790 6,759,289 Noncurrent Assets Due from related parties (Notes 7 and 12) 159,741 150,894 262,435 273,303 Investments and advances (Notes 5, 7, 9, 12 and 15) 3,622,061 3,417,545 239,962 342,111 Noncurrent receivables from Sky Vision (Note 7) 1,800,428 – 1,800,428 – Property and equipment at cost - net (Notes 8, 12, 13 and 14) 10,250,015 10,580,136 10,650,285 10,909,767 Program rights -

For Creative People

creative careers for creative people Film Production Acting for Film, TV & Theatre Writing for Film & TV Fashion Design Marketing for Fashion & Entertainment Interior Decorating Video Game Design & Animation Video Game Design & Development Graphic Design & Interactive Media TORONTO FILM SCHOOL Toronto Film School offers accelerated diploma programs designed to prepare students for fulfilling careers in film production, acting, writing, fashion, interior decorating, video game design and development and graphic design. Students at the Toronto Film School are instructed and mentored by industry professionals who understand what it takes to succeed. Students learn through hands-on projects, immersive instruction and collaboration with their peers. At Toronto Film School, students have the opportunity to transform raw creativity into practical skills for a competitive marketplace in a career they love. Toronto Film School provides an inspiring environment for cross collaboration across creative programs. From students in video game design creating games with acting and writing students, to fashion design students designing costumes for film production students, collaboration is built into the curriculum. Students gain the real-world experience of playing multiple roles and working in cross-industry teams. They also build invaluable networks across disciplines and graduate with more career options. This cross program collaboration and the shared passion of our students and instructors make Toronto Film School one of the most unique educational communities in the world. What Sets Toronto Film School Apart? The city of Toronto is Canada’s Accelerated programs are designed Toronto Film School instructors are epicenter for entertainment and to teach students the right skills working professionals who are active design. -

Low Priced Cialis

Changing Lives Connections One Smile at a Time 2017 HIGHLIGHTS Changing Lives One Smile at a Time…thanks to you! Read about it in our newsletter! A Message from our Leadership More than three million children are hospitalized each year in the United States. Because of you, pediatric patients nation-wide are now benefitting from enCourage Kids. 2017 celebrated a year of growth as we expanded beyond the tristate, and BOARD OF DIRECTORS provided funding and programming to pediatric facilities across 26 states and in Puerto Rico. With a goal of having a presence in all pediatric facilities in the U.S., OFFICERS Chairman we look forward to making the hospital a better place to get better for all sick kids. Jeffrey Gural GFP Real Estate 2017 was also a year full of exciting milestones for enCourage Kids. Through our Executive Vice President & Treasurer Pediatric Hospital Support Program, we exceeded $15M awarded to fund nearly Joseph Wessely 850 projects, hosted the 10th Anniversary Weekend Escape at Camp Pontiac, and Dime Community Bank raised a record-breaking $1.8M at the 32nd Annual Gala. Secretary Mary Krayeske In the Spring of 2017, we partnered with martial artist and world record holder, Leif Con Edison Becker, on his Breaking Barriers campaign. In just 24 hours, he set a record and broke MEMBERS 12,120 boards. His journey represented our courageous and resilient enCourage kids Jay Anderson The Feil Organization overcoming their fears and medical barriers. The event also spread awareness for our Artists4EKF program, which funds creative therapies in the hospital such as Lucy Ball Lone Pine Foundation playroom murals, music therapy, artists-in-residence programs, and creative writing sessions. -

ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation Sgt

ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation Sgt. Esguerra Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines April 19, 2010 Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. Exchange Road, Ortigas Center Pasig City Attention: Ms. Janet A. Encarnacion Head, Disclosure Department Dear Ms. Encarnacion, We hereby submit to the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) the Definitive Information Statement of ABS- CBN Broadcasting Corporation (ABS-CBN or the Company). Based on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) letter dated April 16, 2010, which provided a list of prescribed amendments to the Preliminary Information Statement the Company submitted to the SEC and the PSE last April 13, 2010, we made the following revisions: 1. Updated to March 31, 2010 the following information: a. Number of Shares Outstanding on page 7. b. Security Ownership of Certain Record and Beneficial Owners of more than 5% on page 7. c. Security Ownership of Directors and Management on page 8. d. List of Directors and Executive Officers on pages 9 to 18. e. Top 20 Shareholders on page 50. 2. Disclosure of any relationship of Mr. Oscar M. Lopez with any of the nominees for Independent Director on page 9. 3. Compliance with the five year rotation requirement of external auditor on page 20. 4. Brief reason(s) for and the general effect of the proposed amendment of the Company’s Articles of Incorporation on page 22. 5. Submission of 1st Quarter 2010 report on page 42. 6. Share price information as of the latest practicable trading date (April 19, 2010) on page 49. 7. Disclosure on dividend policy and restrictions on page 49. Thank you. -

Knowledge Channel Powers Through Challenging Times Story on Page 4

NOVEMBER 2020 A monthly publication of the Lopez group of companies www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Knowledge Channel powers through challenging times Story on page 4 Economic impact assessment Rockwell Kapamilya ‘TVP’ partners with Christmas streams on TGN Realty presents YouTube …page 2 …page 7 …page 8 2 Lopezlink November 2020 BIZ NEWS BIZ NEWS Lopezlink November 2020 3 Virtual corporate governance training First Gen gets DOE award to Rockwell enters partnership By Carla Paras-Sison FGEN LNG preferred tenderers THE annual corporate gover- develop pump storage project with TGN Realty to develop nance training of directors and By Joel Gaborni for binding invitation to officers of publicly listed com- panies (PLCs) associated with FIRST Gen Corporation has always available when it’s security and stability. the Lopez Group went virtual been awarded a hydro service needed,” said Ricky Carandang, The hydro service contract mixed-use community on Oct. 23 as conducted by the contract by the Department of First Gen vice president. “But gives First Gen, through First tender for charter of FSRU Institute of Corporate Direc- Energy to develop a 120-mega- with a pump storage facility Gen Hydro, five years to con- venture with the family be- one bedroom to three bedrooms tors (ICD). watt (MW) pumped-storage like the one we want to build in duct predevelopment stage FGEN LNG Corporation has Ltd. and Höegh LNG Asia construction, ownership and hind the successful Nepo Cen- sized 44 sq. m. to 142 sq. m. The The continuing education hydroelectric facility in Aya, Pantabangan, we will be able to activities—from a preliminary expanded the list of preferred Pte. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 830' UD 029 817 TITLE Youth Violence: A Community Resource. Hearing on Experience and Reaction to Trends Regarding Juvenile Violence Within the Jurisdiction of Phoenix and Tucson, AZ, before the Subcommitt.e on Juvenile Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary. United States Senate, One Hundred Third Congress, First Session (Phoenix and Tucson, AZ, June 1-2, 1993). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. REPORT NO ISBN-0-16-043452-1 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 290p.; Serial No. J-103-17. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9325. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) Reports General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; Crime Prevention; *Delinquency Prevention; Hearings; *Juvenile Gangs; Juvenile Justice; Local Issues; *Problem Solving; *Violence; Youth Problems IDENTIFIERS Congress 103rd; Gun Control ABSTRACT Data show that gangs, drugs, and random murders are becoming staples in the lives of U.S. children. Every major U.S. city is facing a deadly gang problem, exemplified by drive-by shootings and teenagers brandishing assault weapons. This document presents witness testimony, prepared stateirentL, and panel discussions that examine the problem of gang violence and the use of firearms by young people within the community, as well as what has and has not worked in attempting to eliminate these p)Iblems at the local level. Panelists include Stanley G. Feldman, Chief Justice of the Arizona Supreme Court; Sophia Lopez, representing Mothers Against Gangs; Lora Nye, chairperson, Phoenix Blockwatch Commission; Robert K. -

Philippines in View a CASBAA Market Research Report

Philippines in View A CASBAA Market Research Report An exclusive report for CASBAA Members Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 4 1.1 Pay-TV Operators 4 1.2 Pay-TV Subscriber Industry Estimates 5 1.3 Pay-TV Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) 5 1.4 Media Ownership of FTAs 6 1.5 Innovations and New Developments 6 1.6 Advertising Spend 6 1.7 Current Regulations 6 2 Philippine TV Market Overview 8 2.1 TV Penetration 8 2.2 Key TV Industry Players 9 2.3 Internet TV and Mobile TV 11 3 Philippine Pay-TV Structure 12 3.1 Pay-TV Penetration Compared to Other Countries 12 3.2 Pay-TV Subscriber Industry Estimates 12 3.3 Pay-TV Subscribers in the Philippines 13 3.4 Pay-TV Subscribers by Platform 14 3.5 Pay-TV Operators’ Market Share and Subscriber Growth 14 3.6 Revenue of Major Pay-TV Operators 16 3.7 Pay-TV Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) 17 3.8 Pay-TV Postpaid and Prepaid Business Model 17 3.9 Pay-TV Distributors 17 3.10 Pay-TV Content and Programming 18 3.11 Piracy in The Philippine Pay-TV Market 20 4 Overview of Philippine Free-To-Air (FTA) Broadcasting 21 4.1 Main FTA Broadcasters 21 4.2 FTA Content and Programming 26 5 Future Developments in the Philippine TV Industry 27 5.1 FTA Migration to Digital 27 5.2 New Developments and Existing Players 28 5.3 Emerging Players and Services 29 Table of Contents 6 Technology in the Philippine TV Industry 30 6.1 6.1 SKYCABLE 30 6.2 Cignal 30 6.3 G Sat 30 6.4 Dream 30 7 Advertising in the Philippine TV Industry 31 7.1 Consumer Affluence and Ability to Spend 31 7.2 General TV Viewing Behaviour 32 7.3 Pay-TV and -

LAAPFF 2015 Catalog

VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS presents the LOS ANGELES ASIAN PACIFIC FILM FESTIVAL APRIL 23 – 30, 2015 No. 31 LITTLE TOKYO _ KOREATOWN _ WEST HOLLYWOOD SEE YOU NEXT YEAR! CONTENTS 7 Festival Welcome 8 Festival Sponsors 10 Community Partners 12 “About VC” Update for 2015 14 Friends of Visual Communications 16 AWC Indiegogo Supporters 18 Year of The Question of the Year! 26 Why Arthur Dong Still Matters 32 Festival Awards: Past Awardees 36 Festival Award Nominees: Feature Narrative 39 Festival Award Nominees: Feature Documentary 42 Festival Award Nominees: Short Film 48 Programmers’ Recommendations 51 Conference for Creative Content 2015 56 Filmmaker Panels & Seminars 60 Program Schedule 61 Box Office Info 62 Venue Info 63 Parties & Afterhours 65 Festival Galas 75 Festival Special Presentations 83 Artist’s Spotlight: Arthur Dong 87 Narrative Competition Films 97 Documentary Competition Films 107 International Showcase Films 123 Short Film Programs 144 Acknowledgements 146 Print & Tape Sources 150 Title/Artist Index 152 Country Index The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 2 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 3 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 4 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 5 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 6 WELCOME Welcome to the 31st edition of presentations, we are extremely proud to showcase the Los Angeles Asian Pacific returning, seasoned, and emerging Asian Pacific Film Festival! American and International artists and their stories to After a 5-year absence, Visual our communities throughout the Festival at the JACCC, Communications is excited to Japanese American National Museum, Downtown open the Festival at the Japanese Independent, The Great Company, CGV Cinemas, and American Cultural & Community the Directors Guild of America. -

Title Bim Price

4 DOCUMENT \l n)! ED 156 850' SP 012 804 TITLE Physical Education fdr Children in California Public Schools Ages Four Through Nine., INSTITUTION' California StWtd Dept. of Education, Sacramento. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 455p. AVAILABLE FROMPublications Sales, California State-Department of Education, P. O. Box 271, Sacramento, CA °95802 ($2.50) BIM PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. BC Not Available from EDRS. .DESCRIPTORS *Early -Childhood Education; shoto;-Development; *Physical Education; *Physical Fitness; Program Planning; Psychomotor Skills; Self Ccncept; Skill Development; Social Behavior ABSTRACT. This publication offers a catalog cf movement and skill opportunities for .a full range cf motor, cognitive, and affective growth. It is designed for teachers responsible fcr directing and teaching physical education pxograms for.children aged four through nine. The following major topics are coveied: (1) ,insights into considerations needed when planning programs; (2) a rationale for selecting effective 'teaching strategies;(3) suggested program goals and objectives; (4)samples of activities that may be used to spur,successful learning in relation to the identified goals and objectiveS; (5) alternatives available for implementation of meaningf01, creative programs;_ (6) suggested scope and seguence of activities for yearly programing;(7) methods of evaluating student progress, teacher effectiveneis, and program success; and (8) supplemental resources in areas of pertinent concern. (JD), k *********************.*******************************4**i44*********44* * .Reproductioni supplied by EDRS' are the best tha be made froathe original document. ********i***********************0********************** ******,****ak** U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THi DOCUMENT HASBEEN REPRO. OUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN. ATING IT POINTS OF VIEWOR OPINIONS.