1 Script – Speech Sqn Ldr Ashcroft Slide 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air & Space Power Journal, September-October 2012, Volume

September–October 2012 Volume 26, No. 5 AFRP 10-1 Senior Leader Perspective Driving towards Success in the Air Force Cyber Mission ❙ 4 Leveraging Our Heritage to Shape Our Future Lt Gen David S. Fadok, USAF Dr. Richard A. Raines Features The Air Force’s Individual Mobilization Augmentee Program ❙ 12 Is the Current Organizational Structure Viable? Col Robin G. Sneed, USAFR Lt Col Robert A. Kilmer, PhD, USA, Retired An Evolution in Intelligence Doctrine ❙ 33 The Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Mission Type Order Capt Jaylan Michael Haley, USAF Joint Targeting and Air Support in Counterinsurgency ❙ 49 How to Move to Mission Command LTC Paul Darling, Alaska Army National Guard Building Partnership Capacity ❙ 65 Operation Harmattan and Beyond Col James H. Drape, USAF Departments 94 ❙ Ira C. Eaker Award Winners 95 ❙ Views An Airman’s Perspective on Mission Command . 95 Col Dale S. Shoupe, USAF, Retired Seeing It Coming: Revitalizing Future Studies in the US Air Force . 109 Col John F. Price Jr., USAF A Misapplied and Overextended Example: Gen J . N . Mattis’s Criticism of Effects-Based Operations . 118 Maj Dag Henriksen, PhD, Royal Norwegian Air Force Academy, US Air Force Research Institute 132 ❙ Historical Highlights Geopolitics versus Geologistics Lt. Col. Harry A. Sachaklian 146 ❙ Ricochets & Replies 154 ❙ Book Reviews Embry-Riddle at War: Aviation Training during World War II . 154 Stephen G. Craft Reviewer: R. Ray Ortensie A Fiery Peace in a Cold War: Bernard Schriever and the Ultimate Weapon . 157 Neil Sheehan Reviewer: Maj Thomas F. Menza, USAF, Retired Khobar Towers: Tragedy and Response . 160 Perry D. Jamieson Reviewer: CAPT Thomas B. -

Operation Anaconda: Playing the War in Afghanistan

Democratic Communiqué 26, No. 2, Fall 2014, pp. 84-106 Medal of Honor: Operation Anaconda: Playing the War in Afghanistan Tanner Mirrlees This article examines the confluence of the U.S. military and digital capitalism in Medal of Honor: Operation Anaconda (MOHOA), a U.S. war-on-Afghanistan game released for play to the world in 2010. MOHOA’s convergent support for the DOD and digital capitalism’s interests are analyzed in two contexts: industry (ownership, development and marketing) and interactive narrative/play (the game’s war simulation, story and interactive play experience). Following a brief discussion of the military-industrial-communications-entertainment complex and video games, I analyze MOHOA as digital militainment that supports digital capi- talism’s profit-interests and DOD promotional goals. The first section claims MO- HOA is a digital militainment commodity forged by the DOD-digital games com- plex and shows how the game’s ownership, development and advertisements sup- port a symbiotic cross-promotional relationship between Electronic Arts (EA) and the DOD. The second section analyzes how MOHOA’s single player mode simu- lates the “reality” of Operation Anaconda and immerses “virtual-citizen-soldiers” in an interactive story about warfare. Keywords: digital militainment, video games, war simulation, war -play, war in Afghanistan, military-industrial-media-entertainment network Introduction: From the Battlefields of Afghanistan to the Battle-Space of Medal of Honor: Operation Anaconda n March 2002, a little less than half a year following U.S. President George W. Bush’s declaration of a global war on terrorism (GWOT), the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) launched “Operation Anaconda.”1 As part of the U.S.-led and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-supported I“Operation Enduring Freedom,” Operation Anaconda was a two-week long and multi- national war-fighting effort to kill Taliban and Al-Qaeda fighters in the Shah-i-Kot Valley and Arma Mountains.2 Operation Anaconda brought together U.S. -

Afghanistan Statistics: UK Deaths, Casualties, Mission Costs and Refugees

Research Briefing Number CBP 9298 Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, By Noel Dempsey 16 August 2021 casualties, mission costs and refugees 1 Background Since October 2001, US, UK, and other coalition forces have been conducting military operations in Afghanistan in response to the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. Initially, military action, considered self-defence under the UN Charter, was conducted by a US-led coalition (called Operation Enduring Freedom by the US). NATO invoked its Article V collective defence clause on 12 September 2001. In December 2001, the UN authorised the deployment of a 5,000-strong International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to deploy in, and immediately around, Kabul. This was to provide security and to assist in the reconstruction of the country. While UN mandated, ISAF continued as a coalition effort. US counter terrorism operations under Operation Enduring Freedom remained a distinct parallel effort. In August 2003, NATO took command of ISAF. Over the next decade, and bolstered by a renewed and expanded UN mandate,1 ISAF operations grew 1 UN Security Council Resolution 1510 (2003) commonslibrary.parliament.uk Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, casualties, mission costs and refugees into the whole country and evolved from security and stabilisation, into combat and counterinsurgency operations, and then to transition. Timeline of major foreign force decisions • October 2001: Operation Enduring Freedom begins. • December 2001: UN authorises the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). • August 2003: NATO assumes ISAF command. • June 2006: ISAF mandate expanded. • 2009: Counterinsurgency operations begin. • 2011-2014: Three-year transition to Afghan-led security operations. • October 2014: End of UK combat operations. -

Suicide Attacks in Afghanistan: Why Now?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship Political Science, Department of Spring 5-2013 SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/poliscitheses Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Mujaddidi, Ghulam Farooq, "SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW?" (2013). Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/poliscitheses/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? by Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Political Science Under the Supervision of Professor Patrice C. McMahon Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Patrice C. McMahon Why, contrary to their predecessors, did the Taliban resort to use of suicide attacks in the 2000s in Afghanistan? By drawing from terrorist innovation literature and Michael Horowitz’s adoption capacity theory—a theory of diffusion of military innovation—the author argues that suicide attacks in Afghanistan is better understood as an innovation or emulation of a new technique to retaliate in asymmetric warfare when insurgents face arms embargo, military pressure, and have direct links to external terrorist groups. -

Afghanistan Bibliography 2019

Afghanistan Analyst Bibliography 2019 Compiled by Christian Bleuer Afghanistan Analysts Network Kabul 3 Afghanistan Analyst Bibliography 2019 Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN), Kabul, Afghanistan This work is licensed under this creative commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode The Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) is a non-profit, independent policy research organisation. It aims to bring together the knowledge, experience and drive of a large number of experts to better inform policy and to increase the understanding of Afghan realities. It is driven by engagement and curiosity and is committed to producing independent, high quality and research-based analysis on developments in Afghanistan. The institutional structure of AAN includes a core team of analysts and a network of contributors with expertise in the fields of Afghan politics, governance, rule of law, security, and regional affairs. AAN publishes regular in-depth thematic reports, policy briefings and comments. The main channel for dissemination of these publications is the AAN web site: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/ Cover illustration: “City of Kandahar, with main bazaar and citadel, Afghanistan.” Lithograph by Lieutenant James Rattray, c. 1847. Coloured by R. Carrick. TABLE OF CONTENTS Bibliography Introduction and Guide ..................................................................... 6 1. Ethnic Groups ................................................................................................... -

Conquering the Elements: Thoughts on Joint Force (Re)Organization

Conquering the Elements: Thoughts on Joint Force (Re)Organization MICHAEL P. NOONAN and MARK R. LEWIS © 2003 Michael P. Noonan and Mark R. Lewis peration Iraqi Freedom demonstrated, or should have demonstrated, that Ojoint warfighting—that is, the synergistic application of the unique capabili- ties of each service so that the net result is a capability that is greater than the sum of the parts—is not just the mantra of the Department of Defense, but is, in fact, a reality. Nevertheless, as successful as Operation Iraqi Freedom was, the depart- ment might take the concept of joint operations to still another level. If Operation Iraqi Freedom provided the observer with glimpses of innovative, task-organized units such as the Army’s elite Delta Force special missions unit working with a pla- toon of M1 Abrams main battle tanks and close air support, we still see a segmenta- tion of the battlespace that creates unnatural seams, inhibiting the full potential of a joint force. How does this square with future joint operational concepts? Can the current architecture of joint force command and control arrangements react re- sponsively and effectively to the threat environment that exists today and will likely confront our forces in the future? Is there a better way? In this article, we will explore those questions as we look at alternative joint force architectures that might better unleash the full capability of the Department of Defense. The Paths to Military Innovation In simple terms, states prepare their militaries for the future by rework- ing, reequipping, or redesigning their forces to better meet their security needs, to develop decisive means, or to ensure their competitive lead in military capabil- ities. -

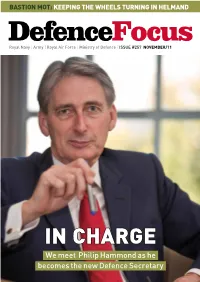

IN CHARGE We Meet Philip Hammond As He Becomes the New Defence Secretary Combatbarbie NANAVIGATORVIGATOR

BASTION MOT: KEEPING ThE wheelS Turning IN hElMAND DefenceFocus Royal Navy | Army | Royal Air Force | Ministry of Defence | issue #257 NOVEMBER/11 IN ChArGE We meet Philip Hammond as he becomes the new Defence secretary combatbarbie NANAVIGATORVIGATOR FINE TUNING: how CIVILIANS keep vehicles BATTLE worThy IN hELMAND p8 p18 Camera, aCtIon Regulars Army and RAF photo competitions p5 In memorIam p22 sIng oUt Tributes to the fallen Gareth Malone on his military wives choir p16 verbatIm p24 ross kemp Head of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary TV presenter returns to Afghanistan p26 my medals p31 CHrIstmas gIveaway WO2 James Palmer looks back Win a selection of HM Armed Forces toys p30 pUZZLES p24 Crossword, chess and sudoku Exclusives p10 Hammond at tHe Helm We talk to the new Defence Secretary p13 prIde of brItaIn Acting Sergeant Pun wins award p22 p14 a MOTHER’s TOUCH p31 Maternal healthcare in Helmand NOVEMBER 2011 | ISSUE 257 | 3 EDITOR’SNOTE DANNY CHAPMAN involvement in the liberation of Libya, DefenceFocus delivered by Chief of Joint Operations, I feel like I often comment, “what a month” Air Marshal Sir Stuart Peach, at a press For everyone in defence on this page. But for this edition I need a few briefing on 27 October. Published by the Ministry of Defence more exclamation marks. Not only have we Much more convenient for our Level 1 Zone C seen the fall of Gaddafi but a new Secretary magazine production deadlines was the MOD, Main Building of State for Defence has, suddenly, arrived. timing of the arrival of the new Secretary of Whitehall London SW1A 2HB I’m writing this on the day we go to print State for Defence, Philip Hammond. -

Land Operations

Land Operations Land Warfare Development Centre Army Doctrine Publication AC 71940 HANDLING INSTRUCTIONS & CONDITIONS OF RELEASE COPYRIGHT This publication is British Ministry of Defence Crown copyright. Material and information contained in this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system and transmitted for MOD use only, except where authority for use by other organisations or individuals has been authorised by a Patent Officer of the Defence Intellectual Property Rights whose details appear below. Crown copyright and Merchandise Licensing, Defence Intellectual Property rights, Central Legal Services, MOD Abbeywood South, Poplar 2 #2214, Bristol BS34 8JH, Email: [email protected] STATUS This publication has been produced under the direction and authority of the Chief of the General Staff by ACOS Warfare branch in his capacity as sponsor of Army Doctrine. It is the individual’s responsibility to ensure that he or she is using the latest version of this publication. If in doubt the individual should contact the Warfare Branch of HQ Field Army (details below). The contents constitute mandatory regulations or an MOD Approved Code of Practice (ACOP) and provide clear military information concerning the most up to date experience and best practice available for commanders and troops to use for operations and training. To avoid criminal liability and prosecution for a breach of health and safety law, you must follow the relevant provisions of the ACOP. Breaches or omissions could result in disciplinary action under the provisions of the Armed Forces Act. DISTRIBUTION As directed by ACOS Warfare. CONTACT DETAILS Suggestions for change or queries are welcomed and should be sent to Warfare Branch Editor, Headquarters Field Army, Land Warfare Development Centre, Imber Road, Warminster BA12 0DJ | i Foreword CGS Foreword to ADP Land Operations ADP Land Operations is the British Army’s core doctrine. -

The Military's Role in Counterterrorism

The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hug etortThe LPapers The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hughes Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. hes Strategic Studies Institute U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA The Letort Papers In the early 18th century, James Letort, an explorer and fur trader, was instrumental in opening up the Cumberland Valley to settlement. By 1752, there was a garrison on Letort Creek at what is today Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. In those days, Carlisle Barracks lay at the western edge of the American colonies. It was a bastion for the protection of settlers and a departure point for further exploration. Today, as was the case over two centuries ago, Carlisle Barracks, as the home of the U.S. Army War College, is a place of transition and transformation. In the same spirit of bold curiosity that compelled the men and women who, like Letort, settled the American West, the Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) presents The Letort Papers. This series allows SSI to publish papers, retrospectives, speeches, or essays of interest to the defense academic community which may not correspond with our mainstream policy-oriented publications. If you think you may have a subject amenable to publication in our Letort Paper series, or if you wish to comment on a particular paper, please contact Dr. Antulio J. Echevarria II, Director of Research, U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 632 Wright Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5046. -

Foreign Support of the U.S. War on Terrorism

Order Code RL31152 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Support of the U.S. War on Terrorism Updated July 11, 2002 Pierre Bernasconi, Tracey Bonita, Ryun Jun, James Pasternak, & Anjula Sandhu Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Steven A. Hildreth Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Support of the U.S. War on Terrorism Summary In response to the terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, a number of countries and organizations pledged various forms of support to the United States in its campaign against the Al Qaeda network and the Taliban in Afghanistan. This report summarizes support for the U.S. war against terrorism from open source material. It will be updated as necessary. For additional information on the U.S. response to terrorism, as well as further country and regional information, see the CRS Terrorism Electronic Briefing Book at: [http://www.congress.gov/brbk/html/ebter1.html]. Contents Overview........................................................1 Response ........................................................2 International Organizations ......................................2 Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) ....................2 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)................2 Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM).........3 European Union (EU) ......................................3 Organization for Security and Cooperation in -

The Role Played by Royal Navy Medical Assistants on Operation Herrick 9 Can We Do More to Prepare Them for Future Operations In

J Royal Naval Medical Service 2010, 96.1 17-22 General The Role played by Royal Navy Medical Assistants on Operation Herrick 9. Can we do more to prepare them for future operations in Afghanistan? D Ablett, L J Herbert, T Brogden Introduction sciences, medical administration and pharmacy. The first ever, independent review of the Defence Their next stage of training lasts 19 weeks and Medical Services by the independent healthcare is mainly hospital-based. It is during this time watchdog for England, The Health Care that MAs are first exposed to a real clinical Commission(1) was published in March 2009. environment. Their practical work on the wards This review was commissioned by the then is reinforced with classroom teaching. The final Surgeon General Lieutenant General Louis stage of training consists of 3 months spent on Lillywhite and in it, the trauma and rehabilitation a ship or at a shore-based RN Medical Centre services for military personnel hurt in battle consolidating learning and achieving key were described as “exemplary”. competencies. Following completion of initial The review praised the care provided to training, MAs are posted to various locations at casualties of war, highlighting the ability to sea, at home and abroad. quickly reach and treat casualties, innovations in MAs were pooled from throughout the Royal the treatment of major injuries, the training of Navy for OpH9. Some were from the Medical staff, design of field hospitals, clinical audits to Squadron of Commando Logistic Regiment feed back important lessons and rehabilitation (CLR) and had spent several months involved in for injured personnel. -

War in Afghanistan: Strategy, Military Operations, and Issues for Congress

War in Afghanistan: Strategy, Military Operations, and Issues for Congress Steve Bowman Specialist in National Security Catherine Dale Specialist in International Security December 3, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40156 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress War in Afghanistan: Strategy, Military Operations, and Issues for Congress Summary With a deteriorating security situation and no comprehensive political outcome yet in sight, most observers view the war in Afghanistan as open-ended. By early 2009, a growing number of Members of Congress, Administration officials, and outside experts had concluded that the effort—often called “America’s other war”—required greater national attention. For the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA), the war is both a struggle for survival and an effort to establish sustainable security and stability. For the United States, the war in Afghanistan concerns the security of Afghanistan and the region, including denying safe haven to terrorists and helping ensure a stable regional security balance. For regional states, including India and Russia as well as Afghanistan’s neighbors Pakistan and Iran, the war may have a powerful impact on the future balance of power and influence in the region. For individual members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the war may be about defeating terrorist networks, ensuring regional stability, proving themselves as contributing NATO members, and/or demonstrating NATO’s relevance in the 21st century. Since 2001, the character of the war in Afghanistan has evolved from a violent struggle against al Qaeda and its Taliban supporters to a multi-faceted counterinsurgency (COIN) effort.