F1911.161E Worksheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 324 International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2019) Exploration on the Protection Scheme of the Great Ruins of Southern Lifang District in the Luoyang City Site in Sui and Tang Dynasties Haixia Liang Luoyang Institute of Science and Technology Luoyang, China Peiyuan Li Zhenkun Wang Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology China Petroleum First Construction Company (Luoyang) Xi'an, China Luoyang, China Abstract—The great ruins are a kind of non-renewable district in a comprehensive and detailed way. Through the precious resources. The southern Lifang district in the analysis of the current situation of southern Lifang district, a Luoyang City Site in Sui and Tang Dynasties is the product of relatively reasonable planning proposal is obtained. This the development of ancient Chinese capital to a certain study can provide theoretical or practical reference and help historical stage. As many important relics and rich cultural on the protection and development of Luoyang City Site in history have been excavated here, the district has a rich Sui and Tang Dynasties, as well as the reconstruction of humanity history. In the context of the ever-changing urban southern Lifang district. construction, the protection of the great ruins in the district has become more urgent. From the point of view of the protection of the great ruins, this paper introduces the II. GREAT RUINS, SUI AND TANG DYNASTIES, LUOYANG important sites and cultural relics of southern Lifang district CITY AND LIFANG DISTRICT in Luoyang city of the Sui and Tang Dynasties through field Great ruins refer to large sites or groups of sites with a investigation and literature review. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Painting Aesthetics and Educational Enlightenment of Ren Renfa in Yuan Dynasty Xiaoli Wu Art College of Xi’An University, 710065

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 132 7th International Conference on Social Science and Education Research (SSER 2017) Painting Aesthetics and Educational Enlightenment of Ren Renfa in Yuan Dynasty Xiaoli Wu Art college of xi’an university, 710065 Keyword: Character Creation; Realistic Analysis; Independent Creation Abstract. Ren Renfa lives in Yuan Dynasty which two dynasties changed, but he wins the later admiration through the water conservancy projects and paintings that surpassed the era. In the balance between reality and ideal, he finds the painting as a media to hit reality and does not avoid social contradictions. His painting style is profound and elegant. Ren Renfa is a water official and his painting perspective and methods are different from other painters, so he is not known to everyone. In the teaching and creating class, we draw on the creative form and the painting style of Ren Renfa in Yuan Dynasty to find a new way of learning for the students' graduation creative course. The Balance between Reality and Ideal - the Seventies of 13th Century that is the Chaos of Times and the Anxiety of Life He was born in a period which has collision of the two nationalities full with big changes and intersection. Mongolia that rapid developed on grassland conquered the Asia-Europe continent. And then Kublai prepared for the strategic layout of the Southern Song Dynasty that period is very turbulent, which was the period Ren Renfa born in. According to historical evidence, he had painted "Xi Chun Tian Ma" and "Wo Wa Tian Ma" for the Song Renzong and he was 20 years old. -

Flowers Bloom and Fall

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository Flowers Bloom and Fall: Representation of The Vimalakirti Sutra In Traditional Chinese Painting by Chen Liu A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2011 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Claudia Brown, Chair Ju-hsi Chou Jiang Wu ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2011 ABSTRACT The Vimalakirti Sutra is one of the classics of early Indian Mahayana Buddhism. The sutra narrates that Vimalakirti, an enlightened layman, once made it appear as if he were sick so that he could demonstrate the Law of Mahayana Buddhism to various figures coming to inquire about his illness. This dissertation studies representations of The Vimalakirti Sutra in Chinese painting from the fourth to the nineteenth centuries to explore how visualizations of the same text could vary in different periods of time in light of specific artistic, social and religious contexts. In this project, about forty artists who have been recorded representing the sutra in traditional Chinese art criticism and catalogues are identified and discussed in a single study for the first time. A parallel study of recorded paintings and some extant ones of the same period includes six aspects: text content represented, mode of representation, iconography, geographical location, format, and identity of the painter. This systematic examination reveals that two main representational modes have formed in the Six Dynasties period (220-589): depictions of the Great Layman as a single image created by Gu Kaizhi, and narrative illustrations of the sutra initiated by Yuan Qian and his teacher Lu Tanwei. -

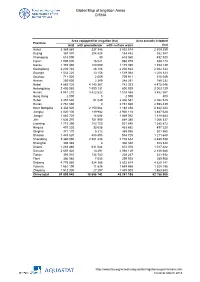

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

The Neolithic Ofsouthern China-Origin, Development, and Dispersal

The Neolithic ofSouthern China-Origin, Development, and Dispersal ZHANG CHI AND HSIAO-CHUN HUNG INTRODUCTION SANDWICHED BETWEEN THE YELLOW RIVER and Mainland Southeast Asia, southern China1 lies centrally within eastern Asia. This geographical area can be divided into three geomorphological terrains: the middle and lower Yangtze allu vial plain, the Lingnan (southern Nanling Mountains)-Fujian region,2 and the Yungui Plateau3 (Fig. 1). During the past 30 years, abundant archaeological dis coveries have stimulated a rethinking of the role ofsouthern China in the prehis tory of China and Southeast Asia. This article aims to outline briefly the Neolithic cultural developments in the middle and lower Yangtze alluvial plain, to discuss cultural influences over adjacent regions and, most importantly, to examine the issue of southward population dispersal during this time period. First, we give an overview of some significant prehistoric discoveries in south ern China. With the discovery of Hemudu in the mid-1970s as the divide, the history of archaeology in this region can be divided into two phases. The first phase (c. 1920s-1970s) involved extensive discovery, when archaeologists un earthed Pleistocene human remains at Yuanmou, Ziyang, Liujiang, Maba, and Changyang, and Palaeolithic industries in many caves. The major Neolithic cul tures, including Daxi, Qujialing, Shijiahe, Majiabang, Songze, Liangzhu, and Beiyinyangying in the middle and lower Yangtze, and several shell midden sites in Lingnan, were also discovered in this phase. During the systematic research phase (1970s to the present), ongoing major ex cavation at many sites contributed significantly to our understanding of prehis toric southern China. Additional early human remains at Wushan, Jianshi, Yun xian, Nanjing, and Hexian were recovered together with Palaeolithic assemblages from Yuanmou, the Baise basin, Jianshi Longgu cave, Hanzhong, the Li and Yuan valleys, Dadong and Jigongshan. -

Artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers Global Chinese Antiques and Art Auction Market B Annual Statistical Report: 2012

GLOBAL CHINESE ANTIQUES AND ART AUCTION MARKET ANNUAL STATISTICAL REPORT 2012 artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers Global Chinese Antiques and Art Auction Market B Annual Statistical Report: 2012 Table of Contents ©2013 Artnet Worldwide Corporation. ©China Association of Auctioneers. All rights reserved. Letter from the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) President ........... i About the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) ................................. ii Letter from the artnet CEO .................................................................. iii About artnet ...................................................................................... iv 1. Market Overview ............................................................................. v 1.1 Industry Scale ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Market Scale ............................................................................. 3 1.3 Market Share ............................................................................. 5 2. Lot Composition and Price Distribution ........................................ 9 2.1 Lot Composition ....................................................................... 10 2.2 Price Distribution ...................................................................... 21 2.3 Average Auction Prices ............................................................. 24 2.4 High-Priced Lots ....................................................................... 27 3. Regional Analysis -

T. (2017) Methological Quality of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses on Acupuncture for Stroke: a Review of Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Chen, X.-L., Mo, C.-W., Lu, L.-y., Gao, R.-Y., Xu, Q., Wu, M.-F., Zhou, Q.-Y., Hu, Y., Zhou, X. and Li, X.-T. (2017) Methological quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on acupuncture for stroke: a review of review. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine, 23(11), pp. 871- 877.(doi:10.1007/s11655-017-2764-6) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/148733/ Deposited on: 18 April 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Methological quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on acupuncture for stroke: a review of reviews* CHEN Xin-lin1, MO Chuan-wei1, LU Li-ya2, GAO Ri-yang1, XU Qian1, WU Min- feng3, ZHOU Qian-yi3, HU Yue1, ZHOU Xuan1, and LI Xian-tao1 1. College of Basic Medical Science, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou (510006), China; 2. Public Health, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland (G12 8RZ), UK; 3. First Clinical College, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou (510405), China Correspondence to: Prof. LI Xian-tao, Tel: 86-20-39358629, E-mail: [email protected] *Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81403296); the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Guangdong Province Colleges and Universities (No. -

A Study of Translation Strategies of Animated Film Titles from the Perspective of Eco- Translatology

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 88-98, January 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1201.09 A Study of Translation Strategies of Animated Film Titles from the Perspective of Eco- translatology Yue Wang Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China Xiaowen Ji University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Abstract—In recent years, the animated film industry is booming and attracting more and more attention. This study, under the guidance of Eco-translatology, revolves around both E-C and C-E animated film title translation, analyzing its translational eco-environment and three-dimensional transformations. Use of main translation strategies of animated film titles, which are transliteration, literal translation, free translation and creative translation, is analyzed. It is found that free translation is the mainstream in both C-E and E-C translation of animated film titles while that creative translation is the least frequently used method. Index Terms—Eco-translatology, animated films, film title translation I. INTRODUCTION With the advance of globalization and China’s reform and opening-up policy, films, as a cross-cultural communication medium, are playing an increasingly important role. Nowadays, animated films, an essential branch of the film industry, are being paid more and more attention to. Not only have a large number of premium English animated films flood into the Chinese film market, but some high-quality Chinese animated films are also released and highly acclaimed by the audiences. As the “face” of a film, a film title is a summary and refinement of the film content. -

Staff and Students

KIB STAFF AND STUDENTS HAN Min CHEN Shao-Tian WANG Ying JI Yun-Heng Director: XUAN Yu CHEN Wen-Yun LI De-Zhu DUAN Jun-Hong GU Shuang-Hua The Herbarium Deputy Directors: PENG Hua (Curator) SUN Hang Sci. & Tech. Information Center LEI Li-Gong YANG Yong-Ping WANG Li-Song ZHOU Bing (Chief Executive) LIU Ji-Kai LI Xue-Dong LIU Ai-Qin GAN Fan-Yuan WANG Jing-Hua ZHOU Yi-Lan Director Emeritus: ZHANG Yan DU Ning WU Zheng-Yi WANG Ling HE Yan-Biao XIANG Jian-Ying HE Yun-Cheng General Administrative Offi ce LIU En-De YANG Qian GAN Fan-Yuan (Head, concurrent WU Xi-Lin post) ZHOU Hong-Xia QIAN Jie (Deputy Head) Biogeography and Ecology XIONG De-Hua Department Other Members ZHAO JI-Dong Head: ZHOU Zhe-Kun SHUI Yu-Min TIAN Zhi-Duan Deputy Head: PENG Hua YANG Shi-Xiong HUANG Lu-Lu HU Yun-Qian WU Yan CAS Key Laboratory of Biodiversity CHEN Wen-Hong CHEN Xing-Cai (Retired Apr. 2006) and Biogeography YANG Xue ZHANG Yi Director: SUN Hang (concurrent post) SU Yong-Ge (Retired Apr. 2006) Executive Director: ZHOU Zhe-Kun CAI Jie Division of Human Resources, Innovation Base Consultant: WU Master' s Students Zheng-Yi CPC & Education Affairs FANG Wei YANG Yun-Shan (secretary) WU Shu-Guang (Head) REN Zong-Xin LI Ying LI De-Zhu' s Group LIU Jie ZENG Yan-Mei LI De-Zhu ZHANG Yu-Xiao YIN Wen WANG Hong YU Wen-Bin LI Jiang-Wei YANG Jun-Bo AI Hong-Lian WU Shao-Bo XUE Chun-Ying ZHANG Shu PU Ying-Dong GAO Lian-Ming ZHOU Wei HE Hai-Yan LU Jin-Mei DENG Xiao-Juan HUA Hong-Ying TIAN Xiao-Fei LIU Pei-Gui' s Group LIANG Wen-Xing XIAO Yue-Qin LIU Pei-Gui QIAO Qin ZHANG Chang-Qin Division of Science and TIAN Wei WANG Xiang-Hua Development MA Yong-Peng YU Fu-Qiang WANG Yu-Hua (Head) SHEN Min WANG Yun LI Zhi-Jian ZHU Wei-Dong MA Xiao-Qing SUN Hang' s Group NIU Yang YUE Yuan-Zheng SUN Hang YUE Liang-Liang LI Xiao-Xian NIE Ze-Long LI Yan-Chun TIAN Ning YUE Ji-Pei FENG Bang NI Jing-Yun ZHA Hong-Guang XIA Ke HU Guo-Wen (Retired Jun. -

The History and Economics of Gold Mining in China

Ore Geology Reviews 65 (2015) 718–727 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ore Geology Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/oregeorev The history and economics of gold mining in China Rui Zhang, Huayan Pian ⁎, M. Santosh, Shouting Zhang School of Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences Beijing, 29 Xueyuan Road, Beijing 100083, China article info abstract Article history: As the largest producer of gold in the world, China's gold reserves are spread across a number of orogenic belts Received 23 January 2014 that were constructed around ancient craton margins during various subduction–collision cycles, as well as with- Received in revised form 4 March 2014 in the cratonic interior along reactivated paleo-sutures. Among the major gold deposits in China is the unique Accepted 5 March 2014 class of world's richest gold mines in the Jiaodong Peninsula in the eastern part of the North China Craton with Available online 20 March 2014 an overall endowment of N3000 tons. Following the dawn of metal in the third millennium BC in western Keywords: China, placer gold mining was soon in practice, particularly during the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. During Gold deposits 1096 AD, mining techniques were developed to dig underground tunnels and the earliest mineral processing Geology technology was in place to pan gold from crushed rock ores. However, ancient China did not witness any History major breakthrough in gold exploitation and production, and the growth in the gold ownership was partly due Economics to the ‘Silk Road’ that enabled the sale of silk products and exquisite artifacts to the west in exchange of gold prod- China ucts.