The History and Economics of Gold Mining in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithium Enrichment in the No. 21 Coal of the Hebi No. 6 Mine, Anhe Coalfield, Henan Province, China

minerals Article Lithium Enrichment in the No. 21 Coal of the Hebi No. 6 Mine, Anhe Coalfield, Henan Province, China Yingchun Wei 1,* , Wenbo He 1, Guohong Qin 2, Maohong Fan 3,4 and Daiyong Cao 1 1 State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, College of Geoscience and Surveying Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] (W.H.); [email protected] (D.C.) 2 College of Resources and Environmental Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China; [email protected] 3 Departments of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering, and School of Energy Resources, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, USA; [email protected] 4 School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Mason Building, 790 Atlantic Drive, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 May 2020; Accepted: 3 June 2020; Published: 5 June 2020 Abstract: Lithium (Li) is an important strategic resource, and with the increasing demand for Li, there are some limitations in the exploitation and utilization of conventional deposits such as the pegmatite-type and brine-type Li deposits. Therefore, it has become imperative to search for Li from other sources. Li in coal is thought to be one of the candidates. In this study, the petrology, mineralogy, and geochemistry of No. 21 coal from the Hebi No. 6 mine, Anhe Coalfield, China, was reported, with an emphasis on the distribution, modes of occurrence, and origin of Li. The results show that Li is enriched in the No. 21 coal, and its concentration coefficient (CC) value is 6.6 on average in comparison with common world coals. -

Download Article

International Conference on Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering (RSETE 2013) Coastline Remote Sensing Monitoring and Change Analysis of Laizhou Bay from 1978 to 2009 Weifu Sun Weifu Sun, Jie Zhang, Guangbo Ren, Yi Ma, Shaoqi Ni Ocean University of China First Institute of Oceanography Qingdao, China Qingdao, China [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Coastline of Laizhou Bay was affected by natural [19]; Zhuang Zhenye et al. studied sand shore erosion of and anthropogenic factors and changed severely in the last 31 eastern Laizhou Bay [20]. Overall, the researchers studied only years. It has great significance to monitor Laizhou Bay coastline partial regions of Laizhou Bay, but not gave the whole change for coastal zone protection and utilization. Based on the situation of coastal Change of Laizhou Bay. extraction of coastline information by selecting 8 remotely sensed In this paper, Landsat images in the year of 1978, 1989, images of MSS and TM in the year of 1978, 1989, 2000 and 2009, changes of coastline of Laizhou Bay is analyzed. The results show 2000 and 2009 were collected to extract coastline information that: (1) The whole coastline of Laizhou Bay kept lengthening by human-machine interaction method. Based on the results of with the speed of 6.04 km/a; (2) The coastline moved 959.2241 4 periods’ coastline extraction, this paper analyzed movement km2 seaward and 0.4934 km2 landward, that is, 958.7307 km2 of coastline and transformation of coastline types. Base on the land area increased in total; (3) Transformation of coastline types results, change factors of the coastline are analyzed. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

Annual Report of Shandong Hi-Speed Co. Ltd. of 2020

Annual Report 2020 Company Code: 600350 Abbreviation of Company: Shangdong Hi-Speed Annual Report of Shandong Hi-Speed Co. Ltd. of 2020 1/265 Annual Report 2020 Notes I. The Board of Directors, Board of Supervisors, directors, supervisors and executives of the Company guarantee the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness without any false or misleading statements or material omissions herein, and shall bear joint and several legal liabilities. II. Absent directors Post of absent director Name of absent director Reason for absence Name of delegate Independent Director Fan Yuejin Because of work Wei Jian III. Shinewing Certified Public Accountants (Special Partnership) has issued an unqualified auditor's report for the Company. IV. Mr. Sai Zhiyi, the head of the Company, Mr. Lyu Sizhong, Chief Accountant who is in charge of accounting affairs, Mr. Zhou Liang, and Chen Fang (accountant in charge) from ShineWing declared to guarantee the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the annual report. V. With respect to the profit distribution plan or common reserves capitalizing plan during the reporting period reviewed by the Board of Directors After being audited by Shinewing Certified Public Accountants (Special Partnership), the net profit attributable to owners of the parent company in 2020 after consolidation is CNY 2,038,999,018.13, where: the net profit achieved by the parent company is CNY2,242,060,666.99. After withdrawing the statutory reserves of CNY224,206,066.70 at a ratio of 10% of the achieved net profit of the parent company, the retained earnings is 2,017,854,600.29 . The accumulated distributable profits of parent company in 2020 is CNY16,232,090,812.89. -

Original Article a Cross-Sectional Survey of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection of Domestic Animals in Laizhou City, Shandong Province, China

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 67, 1-4, 2014 Original Article A Cross-Sectional Survey of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection of Domestic Animals in Laizhou City, Shandong Province, China Shujun Ding1,2†,HaiyingYin3†, Xuehua Xu3, Guosheng Liu3, Shanxiang Jiang3, Weiqing Wang3, Xinqiang Han3,JingyuLiu4, Guoyu Niu5,XiaomeiZhang2, Xue-jie Yu1,6*, and Xianjun Wang2 1School of Public Health, Shandong University, Jinan; 2Shandong Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Jinan; 3Laizhou City Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Laizhou; 4Yantai City Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Yantai; 5China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China; and 6Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA (Received May 5, 2013. Accepted July 16, 2013) SUMMARY: A serosurvey of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) infection in domestic animals was conducted in the rural areas of Laizhou City, Shandong Province, China to deter- mine strategies for control and prevention of SFTS. Serum samples were collected from cattle, goats, dogs, pigs, and chickens and antibodies against SFTSV were detected by double-antigen sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Of 641 serum samples, the SFTSV seropositive rate was 41.8z (268/641): 74.8z,57.1z,52.1z,35.9z,and0z, for goats, cattle, dogs, chickens, and pigs, respectively. We also found that the SFTSV seropositive rates were high among the aged cattle, goats, dogs, and chickens. SFTSV infections existed among cattle, goats, dogs, and chickens in Laizhou City, and goats had the highest seroprevalence. SFTSV seroprevalence increased with an increase in age among animals. -

Human Impact Overwhelms Long-Term Climate Control of Weathering and Erosion in Southwest China

1 Geology Achimer June 2015, Volume 43 Issue 5 Pages 439-442 http://dx.doi.org/10.1130/G36570.1 http://archimer.ifremer.fr http://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00266/37754/ © 2015 Geological Society of America. For permission to copy, contact [email protected]. Human impact overwhelms long-term climate control of weathering and erosion in southwest China Wan S. 1, *, Toucanne Samuel 2, Clift P. D. 3, Zhao D. 1, Bayon Germain 2, 4, Yu Z. 5, Cai G. 6, Yin Xiaoming 1, Revillon Sidonie 7, Wang D. 1, Li A. 1, Li T. 1 1 Key Laboratory of Marine Geology and Environment, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China 2 IFREMER, Unité de Recherche Géosciences Marines, BP70, 29280 Plouzané, France 3 Department of Geology and Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA 4 Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Museum for Central Africa, B-3080 Tervuren, Belgium 5 Laboratoire IDES, UMR 8148 CNRS, Université de Paris XI, Orsay 91405, France 6 Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey, Guangzhou 510760, China 7 SEDISOR/UMR 6538 “Domaines Oceaniques”, IUEM, Place Nicolas Copernic, 29280 Plouzané, France Abstract : During the Holocene there has been a gradual increase in the influence of humans on Earth systems. High-resolution sedimentary records can help us to assess how erosion and weathering have evolved in response to recent climatic and anthropogenic disturbances. Here we present data from a high- resolution (∼75 cm/k.y.) sedimentary archive from the South China Sea. Provenance data indicate that the sediment was derived from the Red River, and can be used to reconstruct the erosion and/or weathering history in this river basin. -

Senior Judge Nicholas Tsoucalas

Slip Op. 07-24 UNITED STATES COURT OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE BEFORE: SENIOR JUDGE NICHOLAS TSOUCALAS ___________________________________ : LAIZHOU AUTO BRAKE EQUIPMENT : COMPANY; LONGKOU HAIMENG MACHINERY : CO., LTD.; LAIZHOU LUQI MACHINERY : CO., LTD.; LAIZHOU HONGDA AUTO : REPLACEMENT PARTS CO., LTD.; : HONGFA MACHINERY (DALIAN) CO.; and : QINGDAO GREN (GROUP) CO. : : Plaintiffs, : : and : : Longkou TLC Machinery Co., Ltd. : : Plaintiff-Intervenor : : v. : Court No. 06-00430 : UNITED STATES : : Defendant, : : and : : THE COALITION FOR THE PRESERVATION : OF AMERICAN BREAK DRUM; : ROTOR AFTERMARKET MANUFACTURERS : : Deft.-Intervenors. : ___________________________________: [Plaintiff-Intervenor’s Motion for Preliminary Injunction to Enjoin Liquidation of Entries is DENIED.] Trade Pacific, PLLC, (Robert G. Gosselink), for Laizhou Auto Brake Equipment Company; Longkou Haimeng Machinery Co., Ltd.; Laizhou Luqi Machinery Co., Ltd.; Laizhou Hongda Auto Replacement Parts Co., Ltd.; Hongfa Machinary (Dalian) Co.; and Qingdao Gren (Group) Co., Plaintiffs. Venable, LLP, (Lindsay Beardsworth Meyer)(Daniel J. Gerkin), for Longkou TLC Machinery Co. Ltd., Plaintiff-Intervenor. Court No. 06-00430 Page 2 Peter D. Keisler, Assistant Attorney General; Jeanne E. Davidson, Acting Director; Commercial Litigation Branch, Civil Division, United States Department of Justice (Stephen Carl Tosini), for the United States, Defendant. Porter, Wright, Morris & Arthur, LLP, (Leslie Alan Glick)(Renata Brandao Vasconcellos), for The Coalition for the Preservation of American -

Study on Spatial Model and Service Radius of Rural Areas And

Study on Spatial Model and Service Radius of Rural Areas and Agriculture Information Level in Yellow-river Delta Yujian Yang1, Guangming Liu2, Xueqin Tong1, Zhicheng Wang1 1.S & T Information Engineering Technology Center of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science, Information center of agronomy College of Shandong University Jinan 250100, P. R. China 2. Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, P. R. China 1 Corresponding author, Address: S&T Information Engineering Research Center, Number 202 Gongye North Road, Licheng District of Jinan, 250100, Shandong Province, P. R. China, Tel: +86-531-83179076, Fax:+86-531-83179821, Email:[email protected] Abstract. Based on the evaluation methods and systems of information measurement level, and according to the principles of agriculture information subject, the study constructed 13 indices system for the measurement of the rural areas and agriculture information level in Yellow-river Delta in 2007. Spatial autocorrelation model of rural areas and agriculture information of 19 country units showed that the comprehensive information level of Hanting, Shouguang, Guangrao, Bincheng, Huimin, Wudi and Yangxin country unit is very significant, has the obvious spatial agglomeration and homogeneity characteristics, but information level agglomeration of Kenli country and Zouping city has the significant heterogeneity, and information level agglomeration characteristics of other 10 country units is not significant. The radius surface of the complicated information level from radial basis function model indicated that rural areas and agriculture information service has a certain service radius, the distance of service radius in theory is 30Km, the gradient and hierarchy is obvious. According to it, the comprehensive service node should be established in Bincheng district and the secondary service node should be set up in Wudi country for improving the service efficiency. -

Inversion of the Degradation Coefficient of Petroleum

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Inversion of the Degradation Coefficient of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Pollutants in Laizhou Bay Shengmao Huang 1,2, Haiwen Han 1,2, Xiuren Li 1,2, Dehai Song 1,2 , Wenqi Shi 3, Shufang Zhang 3,* and Xianqing Lv 1,2,* 1 Physical Oceanography Laboratory, Qingdao Collaborative Innovation Center of Marine Science and Technology (CIMST), Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (H.H.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (D.S.) 2 Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266100, China 3 National Marine Environment Monitoring Center, Dalian 116023, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.Z.); [email protected] (X.L.) Abstract: When petroleum hydrocarbon pollutants enter the ocean, besides the migration under hydrodynamic constraints, their degradation due to environmental conditions also occurs. However, available observations are usually spatiotemporally disperse, which makes it difficult to study the degradation characteristics of pollutants. In this paper, a model of transport and degradation is used to estimate the degradation coefficient of petroleum hydrocarbon pollutants with the adjoint method. Firstly, the results of a comprehensive physical–chemical–biological test of the degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon pollutants in Laizhou Bay provide a reference for setting the degrada- tion coefficient on the time scale. In ideal twin experiments, the mean absolute errors between observations and simulation results obtain an obvious reduction, and the given distributions can be Citation: Huang, S.; Han, H.; Li, X.; inverted effectively, demonstrating the feasibility of the model. -

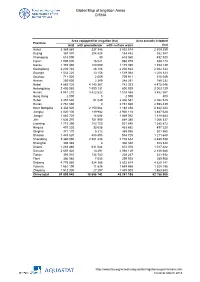

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

The Neolithic Ofsouthern China-Origin, Development, and Dispersal

The Neolithic ofSouthern China-Origin, Development, and Dispersal ZHANG CHI AND HSIAO-CHUN HUNG INTRODUCTION SANDWICHED BETWEEN THE YELLOW RIVER and Mainland Southeast Asia, southern China1 lies centrally within eastern Asia. This geographical area can be divided into three geomorphological terrains: the middle and lower Yangtze allu vial plain, the Lingnan (southern Nanling Mountains)-Fujian region,2 and the Yungui Plateau3 (Fig. 1). During the past 30 years, abundant archaeological dis coveries have stimulated a rethinking of the role ofsouthern China in the prehis tory of China and Southeast Asia. This article aims to outline briefly the Neolithic cultural developments in the middle and lower Yangtze alluvial plain, to discuss cultural influences over adjacent regions and, most importantly, to examine the issue of southward population dispersal during this time period. First, we give an overview of some significant prehistoric discoveries in south ern China. With the discovery of Hemudu in the mid-1970s as the divide, the history of archaeology in this region can be divided into two phases. The first phase (c. 1920s-1970s) involved extensive discovery, when archaeologists un earthed Pleistocene human remains at Yuanmou, Ziyang, Liujiang, Maba, and Changyang, and Palaeolithic industries in many caves. The major Neolithic cul tures, including Daxi, Qujialing, Shijiahe, Majiabang, Songze, Liangzhu, and Beiyinyangying in the middle and lower Yangtze, and several shell midden sites in Lingnan, were also discovered in this phase. During the systematic research phase (1970s to the present), ongoing major ex cavation at many sites contributed significantly to our understanding of prehis toric southern China. Additional early human remains at Wushan, Jianshi, Yun xian, Nanjing, and Hexian were recovered together with Palaeolithic assemblages from Yuanmou, the Baise basin, Jianshi Longgu cave, Hanzhong, the Li and Yuan valleys, Dadong and Jigongshan. -

A Study of Translation Strategies of Animated Film Titles from the Perspective of Eco- Translatology

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 88-98, January 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1201.09 A Study of Translation Strategies of Animated Film Titles from the Perspective of Eco- translatology Yue Wang Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China Xiaowen Ji University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Abstract—In recent years, the animated film industry is booming and attracting more and more attention. This study, under the guidance of Eco-translatology, revolves around both E-C and C-E animated film title translation, analyzing its translational eco-environment and three-dimensional transformations. Use of main translation strategies of animated film titles, which are transliteration, literal translation, free translation and creative translation, is analyzed. It is found that free translation is the mainstream in both C-E and E-C translation of animated film titles while that creative translation is the least frequently used method. Index Terms—Eco-translatology, animated films, film title translation I. INTRODUCTION With the advance of globalization and China’s reform and opening-up policy, films, as a cross-cultural communication medium, are playing an increasingly important role. Nowadays, animated films, an essential branch of the film industry, are being paid more and more attention to. Not only have a large number of premium English animated films flood into the Chinese film market, but some high-quality Chinese animated films are also released and highly acclaimed by the audiences. As the “face” of a film, a film title is a summary and refinement of the film content.