Urban Sociology Paper- Unit-IV Infrastructure in Bangalore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Feasibility Report For

Page 691 of 1031 Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Feasibility Report for the Construction of Proposed Elevated Corridors within Bengaluru Metropolitan Region, Bengaluru Detailed Feasibility Report VOL-IV Environmental Impact Assessment Report Table 4-7: Ambient Air Quality at ITI Campus Junction along NH4 .............................................................. 4-47 Table 4-8: Ambient Air Quality at Indian Express ........................................................................................ 4-48 Table 4-9: Ambient Air Quality at Lifestyle Junction, Richmond Road ......................................................... 4-49 Table 4-10: Ambient Air Quality at Domlur SAARC Park ................................................................. 4-50 Table 4-11: Ambient Air Quality at Marathhalli Junction .................................................................. 4-51 Table 4-12: Ambient Air Quality at St. John’s Medical College & Hospital ..................................... 4-52 Table 4-13: Ambient Air Quality at Minerva Circle ............................................................................ 4-53 Table 4-14: Ambient Air Quality at Deepanjali Nagar, Mysore Road ............................................... 4-54 Table 4-15: Ambient Air Quality at different AAQ stations for November 2018 ............................. 4-54 Table 4-16: Ambient Air Quality at different AAQ stations - December 2018 ................................. 4-60 Table 4-17: Ambient Air Quality at different AAQ stations -

001 Introduction-Oct 07

Comprehensive Traffic & Transportation Plan for Bangalore Chapter 1 - Introduction CHAPTER ––– 1 INTRODUCTION 1.11.11.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND 1.1.1 Bangalore is the fifth largest metropolis (6.5 m in 2004) in India and is one of the fastest growing cities in Asia. It is also the capital of State of Karnataka. The name Bangalore is an anglicised version of the city's name in the Kannada language, Bengaluru. It is globally recognized as IT capital of India and also as a well developed industrial city. 1.1.2 Bangalore city was built in 1537 by Kempegowda. During the British Raj, Bangalore developed as a centre for colonial rule in South India. The establishment of the Bangalore Cantonment brought in large numbers of migrant Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh and North Indian workers for developing and maintaining the infrastructure of the cantonment. New extensions were added to the old town by creating Chamarajpet, Seshadripuram, Nagasandra, Yediyur, Basavanagudi, Malleswaram, Kalasipalyam and Gandhinagar upto 1931. During the post independence period Kumara Park and Jayanagar came into existence. The cantonment area covers nearly dozen revenue villages, which included Binnamangala, Domlur, Neelasandra and Ulsoor to name a few. In 1960, at Binnamangala, new extension named Indiranagar was created. The defence establishments and residential complexes are in part of the core area. It is a radial pattern city growing in all directions. The Bangalore city which was 28.85 sq. Km. in 1901 increased to 174.7 sqkm in 1971 to 272 sqkm in 1986 and presently it has expanded to nearly 437 sqkm. -

Region Name Sol Id Branch Name Ahmedabad 31260

Union Bank of India Authorized Branches for Govt. Small Deposit Savings Scheme ( PPF, Senior Citizen Savings Scheme, Sukanya Samridhhi Yojna and KVP ) REGION NAME SOL ID BRANCH NAME AHMEDABAD 31260 DHANLAXMI MARKET,AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31280 ELLISBRIDGE, AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31290 GANDHI ROAD,AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31300 SSI GOMTIPUR AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31320 MUSEUM AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31330 RAIPUR GATE, AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31340 RELIEF ROAD AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 31350 SSI VADEJ,AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 35350 ASARWA AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 36150 KHANPUR AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 37200 ASHRAM ROAD AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 39180 BHAIRAVNATH ROAD AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 39290 VASNA AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 39330 VASTRAPUR AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 42230 JODHPUR TEKRA AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 43550 C.G. ROAD AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 44910 DR S R MARG AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 45480 BAPUNAGAR, AHMEDABAD BARODA 31050 M G ROAD BARODA BARODA 31060 SAYAJI GUNJ,BARODA BARODA 31230 VALLABH VIDYANAGAR, ANAND BARODA 35020 NIZAMPURA, BARODA BARODA 38110 RAOPURA BARODA BARODA 38600 SAMA BARODA 43390 ALKAPURI BARODA BARODA 46480 RACE COURSE BARODA BARODA 52700 SUBHANPURA-BARODA BARODA 53260 SAYED VASNA ROAD BARODA BARODA 53420 WAGHODIA ROAD BARODA BARODA 61920 KARELIBAUG BARODA 63050 MANJALPUR MEHSANA 31020 HIMMATNAGAR MEHSANA 34260 PATAN MEHSANA 34830 PALANPUR GUJARAT MEHSANA 35930 GANDHINAGAR,GUJARAT MEHSANA 55200 MODASA,GUJRAT MEHSANA 63770 MEHSANA HIGHWAY RAJKOT 31390 JUNAGADH RAJKOT 31400 PORBANDAR RAJKOT 31430 RAJKOT MAIN RAJKOT 31510 JAMNAGAR RAJKOT 34880 KRISHNA NAGAR BHAVNAGAR RAJKOT 35060 BHUJ-RAJKOT -

Bengaluru International Airport Is a 4,050 Acre International Airport That Is Being Built to Serve the City of Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Bengaluru International Airport is a 4,050 acre international airport that is being built to serve the city of Bangalore, Karnataka, India. The airport is located in Devanahalli, which is 30 km from the city The new Bengaluru International Airport at Devanahalli will put Bangalore city on the global destination and offer travelers facilities comparable with the best international airports. The airport will offer quality services and facilities, which will ensure the comfort and ease of travel for all concerned. Construction of the airport began in July 2005, after a decade long postponement Explore this presentation for more information and find out how BIAL is working to make Bengaluru touch the skies and raise the bar for future airports in India. A plan is also being processed for a direct Rail service from Bangalore Cantonment Railway Station to the Basement Rail terminal at the new International Airport. Access on the National Highway is being widened to a six lane expressway, with a 3 feet boundary wall, construction is moving ahead. As of June 2007, a brand new expressway is expected to connect the International Airport to the City's Ring Road. The Expressway will begin at Hennur on the Outer Ring Road. This is expected to be a tolled road. Land Acquisition for the road is expected to be complete by December 2007 and the road would be readied in 18 months since then. Departure – All flights schedule to depart after 00:01 on 30th March 2008 will operate from the new Bangaluru International Airport Arrival – All flights on 29th March 2008 after (20:00) hours may land at the new Bangaluru International Airport or at HAL. -

Mysore Tourist Attractions Mysore Is the Second Largest City in the State of Karnataka, India

Mysore Tourist attractions Mysore is the second largest city in the state of Karnataka, India. The name Mysore is an anglicised version of Mahishnjru, which means the abode of Mahisha. Mahisha stands for Mahishasura, a demon from the Hindu mythology. The city is spread across an area of 128.42 km² (50 sq mi) and is situated at the base of the Chamundi Hills. Mysore Palace : is a palace situated in the city. It was the official residence of the former royal family of Mysore, and also housed the durbar (royal offices).The term "Palace of Mysore" specifically refers to one of these palaces, Amba Vilas. Brindavan Gardens is a show garden that has a beautiful botanical park, full of exciting fountains, as well as boat rides beneath the dam. Diwans of Mysore planned and built the gardens in connection with the construction of the dam. Display items include a musical fountain. Various biological research departments are housed here. There is a guest house for tourists.It is situated at Krishna Raja Sagara (KRS) dam. Jaganmohan Palace : was built in the year 1861 by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in a predominantly Hindu style to serve as an alternate palace for the royal family. This palace housed the royal family when the older Mysore Palace was burnt down by a fire. The palace has three floors and has stained glass shutters and ventilators. It has housed the Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery since the year 1915. The collections exhibited here include paintings from the famed Travancore ruler, Raja Ravi Varma, the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and many paintings of the Mysore painting style. -

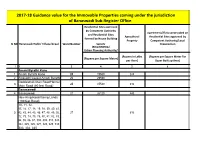

2017-18 Guidance Value for the Immovable Properties Coming Under the Jurisdiction of Banaswadi Sub-Register Office

2017-18 Guidance value for the Immovable Properties coming under the jurisdiction of Banaswadi Sub-Register Office. Residential Sites approved by Competent Authority Apartments/Flats constructed on and Residential Sites Agricultural Residential Sites approved by formed by House Building Property Competent Authority/Local Sl NO Banaswadi Hobli/ Village/Area/ Ward Number Society Organization (BDA/BMRDA/ Urban Planning Authority/ (Rupees in Lakhs (Rupees per Square Meter For (Rupees per Square Meter) per Acre) Super Built up Area) 1 2 3 4 5 6 Amani Byrathi Kane 1 Amani Byrathi Kane 25 19580 245 2 Arkavathi Layout Amani Byrathi 25 29590 Geddalahalli Main Road/Hennur 3 25 45540 610 Main Road (80 feet Road) Banasawadi 4 Banasawadi 27 26100 490 New Ring Road facing Lands (100 feet Road) 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 38, 39, 40, 41, 5 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 27 610 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 308, 309, 310, 323, 324, 325, 326, 327, 328, 329, 332, 333, 334, 335 Banasawadi - 6 Ramamurthy NagaraMain Road 27 46000 (80 feet Road) 7 Ex-Servicemen Colony 27 32560 8 Chandramma Layout 27 32540 9 Kalyanamma Layout 27 32560 10 Lakshmamma Layout 27 32560 11 Green Park Layout 27 32560 12 Vijaya Bank Colony 27 32560 13 Annaiah Reddy Layout 27 32560 14 Skyline Apartments (Apartments) 27 75900 Canapoy Apartments 15 27 37070 (Apartments) 16 Ex- Servicemen Colony/Layout 27 32600 17 Gopala Reddy Layout 27 32600 18 Krishna Reddy Layout 27 32560 19 100 feet Road/10 th Main Road 27 65120 Sai Charita Green Oaks 20 27 55000 (Apartments) -

Bangalore for the Visitor

Bangalore For the Visitor PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 12 Dec 2011 08:58:04 UTC Contents Articles The City 11 BBaannggaalloorree 11 HHiissttoorryoofBB aann ggaalloorree 1188 KKaarrnnaattaakkaa 2233 KKaarrnnaattaakkaGGoovv eerrnnmmeenntt 4466 Geography 5151 LLaakkeesiinBB aanngg aalloorree 5511 HHeebbbbaalllaakkee 6611 SSaannkkeeyttaannkk 6644 MMaaddiiwwaallaLLaakkee 6677 Key Landmarks 6868 BBaannggaalloorreCCaann ttoonnmmeenntt 6688 BBaannggaalloorreFFoorrtt 7700 CCuubbbboonPPaarrkk 7711 LLaalBBaagghh 7777 Transportation 8282 BBaannggaalloorreMM eettrrooppoolliittaanTT rraannssppoorrtCC oorrppoorraattiioonn 8822 BBeennggaalluurruIInn tteerrnnaattiioonnaalAA iirrppoorrtt 8866 Culture 9595 Economy 9696 Notable people 9797 LLiisstoof ppee oopplleffrroo mBBaa nnggaalloorree 9977 Bangalore Brands 101 KKiinnggffiisshheerAAiirrll iinneess 110011 References AArrttiicclleSSoo uurrcceesaann dCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111155 IImmaaggeSS oouurrcceess,LL iicceennsseesaa nndCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111188 Article Licenses LLiicceennssee 112211 11 The City Bangalore Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Bangalore — — metropolitan city — — Clockwise from top: UB City, Infosys, Glass house at Lal Bagh, Vidhana Soudha, Shiva statue, Bagmane Tech Park Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Location of Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) in Karnataka and India Coordinates 12°58′′00″″N 77°34′′00″″EE Country India Region Bayaluseeme Bangalore 22 State Karnataka District(s) Bangalore Urban [1][1] Mayor Sharadamma [2][2] Commissioner Shankarlinge Gowda [3][3] Population 8425970 (3rd) (2011) •• Density •• 11371 /km22 (29451 /sq mi) [4][4] •• Metro •• 8499399 (5th) (2011) Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) [5][5] Area 741.0 square kilometres (286.1 sq mi) •• Elevation •• 920 metres (3020 ft) [6][6] Website Bengaluru ? Bangalore English pronunciation: / / ˈˈbæŋɡəɡəllɔəɔər, bæŋɡəˈllɔəɔər/, also called Bengaluru (Kannada: ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,, Bengaḷūru [[ˈˈbeŋɡəɭ uuːːru]ru] (( listen)) is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of May, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of May, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 324D6 26591 CHIKBALLAPUR 6 7 2 24 26 District 324D6 26593 BANGALORE CITY ANAND 0 0 0 27 27 District 324D6 26595 BANGALORE INDIRANAGAR 7 0 0 32 32 District 324D6 26596 BANGALORE NORTH 6 7 7 47 54 District 324D6 26597 BANGALORE JAYAMAHAL 0 0 1 54 55 District 324D6 26601 BANGALORE SOMESHWARAP 9 10 10 26 36 District 324D6 26616 DODDABALLAPUR 4 5 5 84 89 District 324D6 26639 KOLAR 9 13 9 14 23 District 324D6 26676 TIRUPATI 8 2 8 47 55 District 324D6 29716 HOSKOTE 0 0 4 17 21 District 324D6 30532 CHITTOOR 0 0 3 24 27 District 324D6 31640 GOWRIBIDANUR 0 0 0 35 35 District 324D6 32275 CHINTAMANI 2 2 4 25 29 District 324D6 32992 NELAMANGALA 5 6 5 25 30 District 324D6 33157 BANGALORE VIJAYANAGAR 0 0 1 55 56 District 324D6 33158 DEVANAHALLI 1 1 0 35 35 District 324D6 33193 BANGARAPET 1 0 1 63 64 District 324D6 33610 PEENYA-YESHWANTHPUR L C 9 10 9 36 45 District 324D6 33980 BANGALORE SADASHIVANAGAR 0 0 11 8 19 District 324D6 35008 BANGALORE CENTRAL 2 0 0 25 25 District 324D6 36536 YELAHANKA 6 0 5 41 46 District 324D6 37295 BANGALORE KUMARAPARK 0 0 0 24 24 District 324D6 38758 MADANAPALLE 6 8 7 29 36 District 324D6 39004 PILER 30 31 27 48 75 District 324D6 39101 BANGALORE EAST 1 0 1 82 83 District 324D6 39776 HEBBAL 0 0 5 37 42 District 324D6 39832 PALAMANER 0 0 0 42 42 District 324D6 40576 BANGALORE SESHADRIPURAM 0 0 1 28 29 District 324D6 45754 VIJANAPURA 0 0 1 12 -

Ulsoor Lake: Grey to Green

ISSN (Print) : 0974-6846 Indian Journal of Science and Technology, Vol 8(28), DOI: 10.17485/ijst/2015/v8i28/81896, October 2015 ISSN (Online) : 0974-5645 Ulsoor Lake: Grey to Green S. Meenu*, T. Pavanika, D. Praveen, R. Ushakiran, G. Vinod Kumar and Sheriff Vaseem Anjum Department of Architecture, BMSCE, Autonomous under VTU, Bangalore - 560 019, Karnataka, India; [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Bangalore, when founded by Kempegowda I, faced water scarcity, which was mitigated by the ruler by building reservoirs as tanks and lakes. With rapid urbanisation, the lakes have been encroached upon and have given way to build struc- tures catering to the citizen’s needs. According to study conducted by the Energy and Wetland Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, the 262 wetlands that existed in Bangalore in 1962 has declined by 58% by 2007. Similarly, when the city’s built up area shot up by 466% between 1973 and 2007, the number of lakes came down from 159 to 93. Lakes also sustained over the years due to the active linkages between them, which are now part of the hardscape of the city. With the increase in built environment, the city is losing out on softscapes that help rejuvenate the water table through percolation. The storm water drains established by the erstwhile rulers of Bangalore are turning grey. One of the lakes in Bangalore which is rapidly losing out on its ability to cater to the biodiversity and turning grey is Ulsoor Lake. -

Bengaluru Metro Rail Project Phase 2B (Airport Metro Line) KR Puram to Kempegowda International Airport

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft) Vol. 4 of 6 June 2020 India: Bengaluru Metro Rail Project Phase 2B (Airport Metro Line) KR Puram to Kempegowda International Airport Prepared by Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. (BMRCL), India for the Asian Development Bank. NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of India and its agencies ends on 31 March. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2019 ends on 31 March 2019. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental Impact Assessment - KR Puram to KIA Section of BMRCL Table 4- 15: Results of Ground Water Analysis Std. IS Sl. 10500:2012 Parameters Unit GW3 GW4 No. (Second Revision AL PL 1. pH 6.5-8.5 - 7.32 7.62 2. Colour 5 15 Hazen <1 <1 3. Odour Agreeable -- Agreeable Agreeable 4. Turbidity 1 5 NTU 0.12 0.34 5. Electrical Conductivity Not specified 980 1797 6. Total Dissolved Solids 500 2000 mg/L 668 1217 7. -

LITERATURA CHILENA Creación Y Crítica

LITERATURA CHILENA creación y crítica GUSTAVO BECERRA SCHMIDT / EDUARDO CARRASCO JUAN ARMANDO EPPLE / NAOM1 LINDSTROM PATRICIO MANNS / NANCY MORRIS JUAN ORREGO SALAS / ALFONSO PADILLA OSVALDO RODRIGUEZ / RODRIGO TORRES / DAVID VALJALO JcTUBULIO / SEPTIEMBRE J VERANO / 19185 -------RE / DICIEMBRE / OTONO í 19L.85 EDICIONES DE LA FRONTERA MADRID / ESPAÑA // LOS ANGELES / CALIFORNIA 33/34 INDICE Vol 9 - Nos. 3 y 4 Año 9 - Nos. 33 y 34 LITERATURA CHILENA, creación y crítica Número Doble Especial — Nueva Canción / Canto Nuevo Julio / Diciembre de 1985 Editorial I Tercera Etapa _____ ±_____ David Valjalo 2 Nuestro Canto Juan Orrego-Salas C Espíritu y contenido formal de su música en la Nueva Canción Chilena Gustavo Becerra-Schmidt 14 La música culta y la Nueva Canción Chilena Patricio Manns 22 Problemas del texto en la Nueva Canción Rodrigo Torres 2 5 La urbanización de la canción folklórica Nancy M o r r is ^ O Observaciones acerca del Canto Nuevo Chileno Eduardo Carrasco 32 Quilapayún, la revolución y las estrellas 40 O rografía de Quilapayún Juan Armando Epple'42 Reflexiones sobre un canto en movimiento Alfonso Padilla 47 Inti-lllimani o el cosmopolitismo en la Nueva Canción Osvaldo Rodríguez 50 Con el grupo Los Jaivas a través de Eduardo Parra Alfonso Padilla 54 El grupo lllapu Naomi Lindstrom 56 Construcción folklórica y desconstrucción individual en un texto de Violeta Parra Osvaldo Rodríguez 61 Acercamiento a la canción popular latinoamericana David Valjalo 65 Cantores que reflexionan Juan Armando Epple 66^ Libro Mayor de Violeta Parra 67Catálogo de Alerce Juan Armando Epple *7ZABibliografía Básica sobre la Nueva Canción Chilena y ■ vz el Canto Nuevo LITERATURA CHILENA, creación y critica Directores Invitados Eduardo Carrasco / Patricio Manns Número Especial Nueva Canción / Canto Nuevo DIRECCION: David Valjalo J Guillermo Araya (1931 / 1983) Escriben en este número: TERCERA ETAPA He aquí la iniciación de una nueva etapa en nuestra Gustavo Becerra Schmidr publicación. -

![Bangalore (Or ???????? Bengaluru, ['Be?G??U??U] ( Listen)) Is the Capital City O F the Indian State of Karnataka](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7497/bangalore-or-bengaluru-be-g-u-u-listen-is-the-capital-city-o-f-the-indian-state-of-karnataka-1767497.webp)

Bangalore (Or ???????? Bengaluru, ['Be?G??U??U] ( Listen)) Is the Capital City O F the Indian State of Karnataka

Bangalore (or ???????? Bengaluru, ['be?g??u??u] ( listen)) is the capital city o f the Indian state of Karnataka. Located on the Deccan Plateau in the south-east ern part of Karnataka. Bangalore is India's third most populous city and fifth-m ost populous urban agglomeration. Bangalore is known as the Silicon Valley of In dia because of its position as nation's leading Information technology (IT) expo rter.[7][8][9] Located at a height of over 3,000 feet (914.4 m) above sea level, Bangalore is known for its pleasant climate throughout the year.[10] The city i s amongst the top ten preferred entrepreneurial locations in the world.[11] A succession of South Indian dynasties, the Western Gangas, the Cholas, and the Hoysalas ruled the present region of Bangalore until in 1537 CE, Kempé Gowda a feu datory ruler under the Vijayanagara Empire established a mud fort considered to be the foundation of modern Bangalore. Following transitory occupation by the Ma rathas and Mughals, the city remained under the Mysore Kingdom. It later passed into the hands of Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, and was captured by the Bri tish after victory in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1799), who returned administr ative control of the city to the Maharaja of Mysore. The old city developed in t he dominions of the Maharaja of Mysore, and was made capital of the Princely Sta te of Mysore, which existed as a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj. In 1809, the British shifted their cantonment to Bangalore, outside the old city , and a town grew up around it, which was governed as part of British India.