Conservation Unit Allows Assessing Vulnerability and Setting Conservation Priorities for a Mediterranean Endemic Plant Within the Context of Extreme Urbanization M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papilio Alexanor Esper from Italian Maritime Alps: a New Subspecies (Lepldoptera: Papilionldae) 75-79 ©Ges

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Atalanta Jahr/Year: 1991 Band/Volume: 22 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sala Giovanni, Bollino Maurizio Artikel/Article: Papilio alexanor Esper from Italian Maritime Alps: a new subspecies (Lepldoptera: Papilionldae) 75-79 ©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (Dec. 1991) 22(2/4):75-79, colour plates XVII-XVIII, Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 Papilio alexanor Esper from Italian Maritime Alps: a new subspecies (Lepldoptera: Papilionldae) by Giovanni Sala & maurizio Bollino received 2.1.1991 Riassunto: li autori descrivono Papilio alexanor radighierii nov. subspec. della Val Gesso (CN), Alpi Marittime Italiane. Vengono fornite alcune notizie sulla biología ed ecologia della nuova sottospecie. Abstract: A new subspecies of Papilio alexanor Esper from Val Gesso (Cuneo Province), Italian Maritime Alps, is described and named radighierii. Some notes about its biology and ecology are given. Introduction The presence and distribution of Papilio alexanor Esper in Italy have not been modified from 1927 until today, except for its confirmed presence in Sicily (Henricksen , 1981) and the Italian Maritime Alps (Balletto & Toso, 1976). Verity (1947) had reported the species in Sicily (Nizza di Sicilia), Calabria (S. Luca) and the oriental Maritime Alps. During some investigations into the Italian Papilionidae the authors, especially because of indications and the kind cooperation of Elvio Córtese and Camillo Forte , put together a significant number of specimens collected in Val Gesso (Cuneo Province) and made observations about their larval and imaginal stages. The results of the morphological analysis compared with those obtained from the nominal subspecies and P. -

S.S. N.21 "Della Maddalena" Variante Agli Abitati Di Demonte, Aisone E Vinadio Lotto 1

S.S. n.21 "della Maddalena" Variante agli abitati di Demonte, Aisone e Vinadio Lotto 1. Variante di Demonte PROGETTO DEFINITIVO PROGETTAZIONE: I PROGETTISTI: ing. Vincenzo Marzi Ordine Ing. di Bari n.3594 ing. Achille Devitofranceschi Ordine Ing. di Roma n.19116 geol. Flavio Capozucca Ordine Geol. del Lazio n.1599 RESPONSABILE DEL SIA DUFK*LRYDQQL0DJDUz Ordine Arch. di Roma n.16183 IL COORDINATORE PER LA SICUREZZA IN FASE DI PROGETTAZIONE geom. Fabio Quondam VISTO: IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO : LQJ1LFROz&DQHSD PROTOCOLLO DATA CODICE PROGETTO NOME FILE REVISIONE SCALA: PROGETTO LIV. PROG. N. PROG. CODICE - DP T O0 5 D 1 6 0 1 ELAB. C B A EMISSIONE A SEGUITO DI RICHIESTA MiTE N. 23984 DEL 8/03/2021 APR 2021 REV. DESCRIZIONE DATA REDATTO VERIFICATO APPROVATO Revised version adopted in Habitat Committee 26.4.2012 ANNEX Form for submission of information to the European Commission according to Art. 6(4) of the Habitats Directive Member State: Italy Date: 13/04/2021 Information to the European Commission according to Article 6(4) of the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) Documentation sent for: information X opinion Art. 6(4).1 Art. 6(4).2 Competent national authority: Ente di gestione Aree Protette Alpi Marittime (Management body for the protected areas of the Maritime Alps) Address: Piazza Regina Elena 30 -12010 Valdieri (CN) Contact person: Tel., fax, e-mail: Tel. +39 0171 976800 Fax +39 0171 976815 [email protected] [email protected] Is the notification containing sensitive information? If yes, please specify and justify 25 1. PLAN OR PROJECT Name of the plan/project: S.S. -

The Wolf Population in the Alps: Status and Management

Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/000807 WOLFALPS Wolf in the Alps: implementation of coordinated wolf conservation actions in core areas and beyond Action E8 – Annual thematic conference PROCEEDINGS II CONFERENCE LIFE WOLFALPS The wolf population in the Alps: status and management CUNEO , 22 ND JANUARY 2016 May 2016 Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/000807 WOLFALPS nd Proceedings of the II Conference LIFE WolfAlps - Cuneo 22 January 2016 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Suggested citation: Author of the abstract, Title of the abstract , 2016, in F. Marucco, Proceedings II Conference LIFE WolfAlps – The wolf population in the Alps: status and management, Cuneo 22 nd January 2016, Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/00080 WOLFALPS. Proceedings prepared by F. Marucco, Project LIFE WolfAlps, Centro Gestione e Conservazione Grandi Carnivori, Ente di Gestione delle Aree Protette delle Alpi Marittime. Download is possible at: www.lifewolfalps.eu/documenti/ The II Conference LIFE WolfAlps “The wolf population in the Alps: status and management” has been held in Cuneo on the 22 nd January 2016, at the meeting Center of the Cuneo Province, C.so Dante 41, Cuneo (Italy), and it has been organized in partnership with: Initiative realized thanks to LIFE contribution, a financial instrument of the European Union. Website: www.lifewolfalps.eu 2 Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/000807 WOLFALPS nd Proceedings of the II Conference LIFE WolfAlps - Cuneo 22 January 2016 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Foreword The Conference LIFE WolfAlps addressed the issue of the natural return of the wolf in the Alps : gave an update on the status of the population in each Alpine country, from France to Slovenia, and discussed the species’ conservation on the long term, also touching the debated topic of its management. -

How to Get There Services in the Park

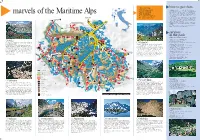

Take nothing how to get there but photographs. Alpi Marittime Nature Park is in the south west Piedmont, on the border between Italy and France, to reach it you get off the Torino-Savona motorway Leave nothing at the Fossano junction and follow the signs for Cuneo and then Borgo San Dalmazzo. The latter is a small town at the junction of three valleys that the marvels of the Maritime Alps but footprints. parks touches. From here you can reach the four villages that play host to the park: Vernante (in Valle Vermenagna), Entracque and Valdieri (Valle Gesso) and Let your memories Aisone (Valle Stura). Vernante is 25 km from Cuneo on the SS.20 Colle di Tenda road, coming from be your souvenirs. the coast it is easier to come up the Roya valley from Ventimiglia through the Colle di Tenda tunnel which brings you out in Vermenagna valley, this is the best way to reach the park from the south. Vernante can also be reached by train on the Torino-Cuneo-Ventimiglia line. Valdieri and Entracque are 18 km and 25 km from Cuneo respectively you follow the SS.20 to Borgo San Dalmazzo, to turn off here for Terme di Valdieri- Entracque. Aisone in the Stura valley is 32 km from Cuneo through Borgo San Dalmazzo along the SS.21 for the Colle della Maddalena road. services in the park office and visitor centres •Valdieri, Director’s office and Administration Piazza Regina Elena, 30 – 12010 Valdieri Sella tel. 0171 97397 – fax 0171 97542 Rio Meris falls towards S.Anna in a string of bubbling Palanfré e-mail: [email protected] – website: www.parcoalpimarittime.it pools and waterfalls. -

The Wolf Population in the Alps: Status And

LIFE WOLFALPS CONFERENCE Participation is open to the public and free. THE WOLF POPULATION IN THE ALPS: Due to the limited availability of seats, STATUS AND MANAGEMENT registration is compulsory. Cuneo – 22nd of January 2016 The LIFE WolfAlps Conference Centro Incontri Provincia di Cuneo, is also organized in collaboration with the For registration send an email to: [email protected] Corso Dante 41 Italian Delegation of the Alpine Convention, which for the occasion will host a meeting of the indicating name/surname/institution Platform WISO (if applicable) (Large Carnivores, Wild Ungulates and Society) or call + 39 0171 97 68 20 that will take place on 20th – 21st of January at the Marittime Alps Natural Park in Valdieri. WITH THE COLLABORATION OF PROJECT PARTNERS: The event is organized in partnership with the 21° Memorial “Danilo Re” by Marguareis Natural Park and Maritime Alps Natural Park, a sporting event that will take place on the 21st - 24th of January 2016 in Chiusa Pesio, which involve the staff of Alpine protected areas. A video, testimony of the commitment of some Alpine Protected Areas in wolves’ monitoring and conservation programs, will be presented later in the day. IN PARTNERSHIP WITH: www.lifewolfalps.eu Initiative realized thanks to LIFE contribution, a financial instrument of the European Union. Ph: Gabriele Cristiani CONFERENCE PROGRAM 1ST SESSION - MORNING 2ND SESSION - AFTERNOON Italian language with English translation English language with translation in Italian / French / German / Slovenian THE LIFE -

George Macdonald in Liguria

George MacDonald in Liguria Giorgio Spina e know that our author and his family went to Northern Italy for Whealth reasons. Biographers such as Joseph Johnson and Greville MacDonald are full of particulars about the dreadful persecution he suffered from the so-called “family attendant” and his continual search for health. In order to retrace the halting places of his lifelong struggle, I mention his stay at Kingswear on the Channel coast in 1856 and, the same year, at Lynton on the opposite coast of the Bristol Channel. We know, moreover, that he wintered in Algiers, and the following year (1857) he rented Providence House, renamed Huntly Cottage, at Hastings. Only a few years later, in 1863, he changed his London dwelling place, moving from Regent’s Park area to Earl’s Terrace, Kensington, because of the clay ground of the former and the healthier dryness of the latter. In 1867 the MacDonald family spent their holidays at Bude in Cornwall, and in 1875 they found a warmer climate at Guildford, Surrey, and then at Boscombe (Bournemouth). It appears that all these removals did not give them a final and satisfactory solution. Probably the ideal climate did not exist in Britain. But at last a new horizon did open. Just at the end of September 1877, Louisa MacDonald, along with Lilia, Irene, and Ronald, arrived in Genoa from Mentone. It was not by chance, but the result of a decision the MacDonald family had taken, surely advised to do so by friends and physicians. Liguria was then well reputed among the English as a particularly [end of page 19] healthy region of Italy. -

English Summaries

English summaries Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: Histoire des Alpes = Storia delle Alpi = Geschichte der Alpen Band (Jahr): 6 (2001) PDF erstellt am: 30.09.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch ENGLISH SUMMARIES WOLFGANG KAISER, A EUROPEAN BORDER REGION: THE MARITIME ALPS, ALPI MARITTIME OR ALPES MARITIMES The history of the Alpi Marittime or Alpes Maritimes is marked by numerous transformations. In the longue duree the non-consistency of political belongmg on the one hand, and linguistic and cultural traditions on the other, form a constant feature that provides this region with a peculiar tension. Still today this makes itself clear to the foreigner and traveller journeying from Menton to Ventimiglia and on to the Col de Tende and some time no longer being completely aware what country he is actually in. -

Illustrations of the Passes of the Alps”

Note di viaggio riferite agli anni 1826/1828 tratte da: “Illustrations of the passes of the Alps” by wich Italy communicates with France, Switzerland, Germany by William Brockedon F.R.S. member of the academies of fine arts at Florence and Rome London 1836 – II edition pagine 61-68 (la prima edizione è del 1828) Vol. II Capitolo The Tende and the Argentiere ROUTE FROM NICE TO TURIN, by THE PASS OF THE COL DE TENDE. NICE has long possessed the reputation of having a climate and a situation peculiarly favourable to those invalids who arrive there from more northern countries; a circumstance that probably led to the improvements of the road which lies between this city and Turin, by the Col de Tende. The situation of Nice is strikingly beautiful from many points of view in its neighbourhood, and many interesting remains of antiquity may be visited in short excursions from the city: these are sources of enjoyment within the reach of the valetudinarian, and add to the pleasures and advantages of a residence at Nice; but they are principally to be found coastways. The rich alluvial soil at the mouth of the Paglione, that descends from the Maritime Alps, gives a luxuriant character to the plain, which, near Nice, is covered with oranges, olives, vines, and other productions of a southern climate; but the moment this little plain is left, on the road to Turin, and the ascent commences towards Lascarene, the traveller must bid adieu to the country where "the oil and the wine abound." The sudden change to stones and sterility, with here and there a stunted, miserable-looking olive-tree, is very striking; and the eye scarcely finds any point of relief from this barrenness until the little valley appears in which Lascarene is situated. -

AEMH 08-039 National Report Italy.Doc

ASSOCIATION EUROPÉENNE DES MÉDECINS DES HÔPITAUX EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF SENIOR HOSPITAL PHYSICIANS EUROPÄISCHE VEREINIGUNG DER LEITENDEN KRANKENHAUSÄRZTE EUROPESE VERENIGING VAN STAFARTSEN DEN EUROPÆISKE OVERLÆGEFORENING ΕΥΡΩΠΑЇΚΟΣ ΣΥΛΛΟΓΟΣ NΟΣΟΚΟΜΕΙΑΚΩΝ I∆TPΩN ∆IΕΥΘΥΝΤΩΝ ASSOCIAZIONE EUROPEA DEI MEDICI OSPEDALIERI DEN EUROPEISKE OVERLEGEFORENING ASSOCIAÇAO EUROPEIA DOS MÉDICOS HOSPITALARES ASOCIACIÓN EUROPEA DE MÉDICOS DE HOSPITALES EUROPEISKA ÖVERLÄKARFÖRENINGEN EVROPSKO ZDRŽENJE BOLNIŠNIČNIH ZDRAVINIKOV EUROPSKA ASOCIACIA NEMOCNICNÝCH LEKAROV EUROPSKA UDRUGA BOLNIČKIH LIJEČNIKA ЕВРОПЕЙСКА АСОЦИАЦИЯ НА СТАРШИТЕ БОЛНИЧНИ ЛЕКАРИ Document : AEMH 08-039 Title: National Report Italy Author : Dr Pier Maria Morresi Purpose : Information Distribution : AEMH Member Delegations Date : 28 April 2008 AEMH-European Secretariat – Rue Guimard 15 – B-1040 Brussels Tel. +32 2 736 60 66, Fax +32 2 732 99 72 e-mail : [email protected], http://www.aemh.org 1 AEMH 08-039 National Report Italy.doc NATIONAL REPORT ITALY st 61 AEMH Meeting, Zagreb 1-3 . May . 2008 HEALHCARE PROFESSIONAL CROSSING BORDERS The policy of being interested in the healthcare-related issues across the borders had a strong development during the last decade of the last century and the first decade of the current one. The Physicians Associations belonging to the provinces located on the borders started getting in touch with their counterparts across the borders. First there was a phase centred on scientific exchanges, entailing a comparison of the acquired skills (this was the easiest phase), then they moved on to pinpointing the shared vital points with regard to the managing of their professional dimension. During the last 30 years, the Italian national healthcare system transitioned from a country-level national model to a regional management model. -

Glacier Extent and Climate in the Maritime Alps During the Younger Dryas 2 Matteo Spagnolo1, Adriano Ribolini2

1 Glacier extent and climate in the Maritime Alps during the Younger Dryas 2 Matteo Spagnolo1, Adriano Ribolini2 3 1 School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen (UK) (corresponding author: [email protected]) 4 2 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita’ di Pisa (Italy) 5 6 Keywords: Younger Dryas; glacier reconstruction; equilibrium line altitude; palaeoclimate; 7 cosmogenic dates; Maritime Alps 8 9 Abstract 10 This study focuses on an Egesen-stadial moraine located at 1906-1920 m asl in the NE Maritime Alps, 11 Europe. Three moraine boulders are dated, via cosmogenic isotope analyses, to 12,490 ± 1120, 12,260 12 ± 1220 and 13,840 ± 1240 yr, an age compatible with the Younger Dryas cooling event. The 13 reconstructed glacier that deposited the moraine has an equilibrium line altitude of 2349 ± 5 m asl, 14 calculated with an Accumulation Area Balance Ratio of 1.6. The result is very similar to the equilibrium 15 line altitude of another reconstructed glacier that deposited a moraine also dated to Younger Dryas, 16 in the SW Maritime Alps. The similarity suggests comparable climatic conditions across the region 17 during the cooling event. The Younger Dryas palaeoprecipitation is 1549 ±26 mm/yr, calculated using 18 the empirical law that links precipitation and temperature at a glacier equilibrium line altitude, with 19 palaeotemperatures obtained from nearby palynological and chironomids studies. The 20 palaeoprecipitation is similar to the present, thus indicating non-arid conditions during the Younger 21 Dryas. This is probably due to the Maritime Alps peculiar position, at the crossroads between air 22 masses from the Mediterranean and the North Atlantic, the latter displaced by the southward 23 migration of the polar front. -

Rome and the Cottians in the Western Alps Carolynn Roncaglia Santa Clara University, [email protected]

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Classics College of Arts & Sciences Fall 2013 Client prefects?: Rome and the Cottians in the Western Alps Carolynn Roncaglia Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/classics Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Carolynn Roncaglia. 2013. “Client prefects?: Rome and the Cottians in the Western Alps”. Phoenix 67 (3/4). Classical Association of Canada: 353–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7834/phoenix.67.3-4.0353. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIENT PREFECTS?: ROME AND THE COTTIANS IN THE WESTERN ALPS Carolynn Roncaglia introduction When Augustus and the Romans conquered the central and western Alps at the end of the first century b.c.e., most of the newly subjugated regions were brought under direct Roman control. The central portion of the western Alps, however, was left in the hands of a native dynasty, the Cottians, where it remained until the reign of Nero over a half-century later. The Cottians thus serve as one of many examples of a form of indirect Roman rule, its “two-level monarchy,” wherein the rulers of smaller kingdoms governed as friends and allies of the Roman state in an asymmetrical power relationship with Rome.1 This article explores how a native dynasty like the Cottians presented and legitimized their relationship with Rome to a domestic audience. -

Maritime Alps 2007

The Maritime Alps Wildlife at Leisure A Greentours Tour Report 4th to 12th July 2018 Led by Paul Cardy Daily Accounts and Systematic Lists written by Paul Cardy The third of the Greentours summer Alpine trilogy, following on from the Dolomites and the Central Italian Alps, was an excellent week in the western Alps, on both the French and Italian sides of the glorious Maritime Alps. Even after eighteen years of leading tours here, and living just to the north in Italy, the area still holds some surprises. The wealth of flowers was a daily feature, and among many plant highlights were Allium narcissiflorum, Saxifraga cochlearis, and Saxifraga callosa all in fine flower, the latter locally abundant cascading from cliffs and walls. Notable were the beautiful endemic Viola valderia, many of the local speciality Nigritella corneliana, Primula latifolia, Gentiana rostanii, Phyteuma globulariifolium, and the endemic Knautia mollis. It was also a very good season for butterflies, stand outs including Clouded Apollo, White-letter Hairstreak, Large Blue, Ripart’s Anomalous Blue, Duke of Burgundy, Southern White Admiral, Large Tortoiseshell, Twin-spot Fritillary, Lesser-spotted Fritillary (rare here), Grison’s Fritillary, False Mnestra Ringlet, and Lulworth Skipper. Our hotel for the week was situated in the hamlet of Casterino, on the eastern boundary of the Mercantour National Park. The fine location allowed easy access to a great variety of habitats, the length of the Roya valley, lower Mediterranean influenced sites, the Val de Merveilles, and the Italian Alpi Maritime, a superbly productive area. We enjoyed superb dinners in the hotel’s excellent restaurant, complete with log fire and paintings of such subjects as Ibex standing among Saxifraga florulenta! Although we were in France, the area has a distinct Italian feel.