George Macdonald in Liguria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progetto Di Revisione Del Piano Di Gestione Dell'accordo Pelagos

Accord créant le Sanctuaire Accordo per la costituzione pour les mammifères marins del Santuario per i mammiferi marini en Méditerranée nel Mediterraneo 8ème Comité Scientifique et Technique 8o Comitato Scientifico e Tecnico 14 octobre 2015, Gênes 14 Ottobre 2015, Genova Pelagos_CST8_Doc07 Français / Italiano Distribution / Pubblicazione: 12/10/2015 Progetto di revisione del Piano di Gestione dell’Accordo Pelagos relativo alla creazione nel Mediterraneo di un Santuario per i Mammiferi Marini Biennio 2016-2017 PARTE 5: ALLEGATI 2015 Documento di lavoro, si prega di non divulgare Sommario ALLEGATO 1: TESTO DELL’ACCORDO PELAGOS RELATIVO ALLA CREAZIONE NEL MEDITERRANEO DI UN SANTUARIO PER I MAMMIFERI MARINI 3! ALLEGATO 2: LISTA DEI COMUNI DI CUI IL TERRITORIO MARITIMO È INCLUSO NEL SANTUARIO PELAGOS 11! ALLEGATO 3: PRIORITÀ DI RICERCA STABILITE DAL 6° COMITATO SCIENTIFICO E TECNICO DELL’ACCORDO PELAGOS 14! ALLEGATO 4: LISTA NON ESAUSTIVA DEI PARTNER DEL SANTUARIO PELAGOS 34! 2 Allegato 1: testo dell’Accordo Pelagos relativo alla creazione nel Mediterraneo di un Santuario per i mammiferi marini ACCORDO RELATIVO ALLA CREAZIONE NEL MEDITERRANEO DI UN SANTUARIO PER I MAMMIFERI MARINI 3 Le Parti del presente Accordo, Considerando le minacce che gravano sui mammiferi marini nel Mediterraneo e particolarmente sul loro habitat; Considerando che nel Mare Mediterraneo esiste una zona di ripartizione di questi animali particolarmente importante per la loro conservazione ; Considerando che, sulla base della Convenzione delle Nazioni Unite sul diritto -

Papilio Alexanor Esper from Italian Maritime Alps: a New Subspecies (Lepldoptera: Papilionldae) 75-79 ©Ges

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Atalanta Jahr/Year: 1991 Band/Volume: 22 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sala Giovanni, Bollino Maurizio Artikel/Article: Papilio alexanor Esper from Italian Maritime Alps: a new subspecies (Lepldoptera: Papilionldae) 75-79 ©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (Dec. 1991) 22(2/4):75-79, colour plates XVII-XVIII, Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 Papilio alexanor Esper from Italian Maritime Alps: a new subspecies (Lepldoptera: Papilionldae) by Giovanni Sala & maurizio Bollino received 2.1.1991 Riassunto: li autori descrivono Papilio alexanor radighierii nov. subspec. della Val Gesso (CN), Alpi Marittime Italiane. Vengono fornite alcune notizie sulla biología ed ecologia della nuova sottospecie. Abstract: A new subspecies of Papilio alexanor Esper from Val Gesso (Cuneo Province), Italian Maritime Alps, is described and named radighierii. Some notes about its biology and ecology are given. Introduction The presence and distribution of Papilio alexanor Esper in Italy have not been modified from 1927 until today, except for its confirmed presence in Sicily (Henricksen , 1981) and the Italian Maritime Alps (Balletto & Toso, 1976). Verity (1947) had reported the species in Sicily (Nizza di Sicilia), Calabria (S. Luca) and the oriental Maritime Alps. During some investigations into the Italian Papilionidae the authors, especially because of indications and the kind cooperation of Elvio Córtese and Camillo Forte , put together a significant number of specimens collected in Val Gesso (Cuneo Province) and made observations about their larval and imaginal stages. The results of the morphological analysis compared with those obtained from the nominal subspecies and P. -

EC-SQUARE - Eradication and Control of Grey Squirrel: Actions for Preservation of Biodiversity in Forest Ecosystems LIFE09 NAT/IT/000095

EC-SQUARE - Eradication and control of grey squirrel: actions for preservation of biodiversity in forest ecosystems LIFE09 NAT/IT/000095 Project description Environmental issues Beneficiaries Administrative data Read more Contact details: Project Manager: Giorgio BONALUME Tel: 0039-02-67652492 Fax: +39 2 67655414 Email: [email protected] Project description: Background Grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) are acknowledged as an invasive alien species which has threatened the native Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) in the British Isles and parts of northern Italy. The grey squirrel can also cause extensive damage to trees through bark-stripping, which affects re-growth and natural tree reproduction in commercial plantations and other forest ecosystems. The spread of grey squirrel in northern Italy represents a problem for the entire European continent, since from Italy the alien species is predicted to colonise surrounding countries, particularly France and Switzerland. Objectives The main objective of the EC-SQUARE project was to control and eradicate threats caused by grey squirrel (and other non-native squirrel species) in different socio-ecological contexts, in three different regions of northern Italy: Lombardy (Lombardia), Liguria and Piedmont (Piemonte). The aim was to produce a decision support system to identify the most efficient management strategy in each case, and to elaborate best practice guidelines for grey squirrel control and eradication. In addition, the project planned to carry out conservation actions in each region to improve habitat quality and/or connectivity of forests patches for red squirrel. Red squirrel will be reintroduced on a site in Lombardy to establish a minimum viable population, following the on a site in Lombardy to establish a minimum viable population, following the removal of grey squirrels. -

S.S. N.21 "Della Maddalena" Variante Agli Abitati Di Demonte, Aisone E Vinadio Lotto 1

S.S. n.21 "della Maddalena" Variante agli abitati di Demonte, Aisone e Vinadio Lotto 1. Variante di Demonte PROGETTO DEFINITIVO PROGETTAZIONE: I PROGETTISTI: ing. Vincenzo Marzi Ordine Ing. di Bari n.3594 ing. Achille Devitofranceschi Ordine Ing. di Roma n.19116 geol. Flavio Capozucca Ordine Geol. del Lazio n.1599 RESPONSABILE DEL SIA DUFK*LRYDQQL0DJDUz Ordine Arch. di Roma n.16183 IL COORDINATORE PER LA SICUREZZA IN FASE DI PROGETTAZIONE geom. Fabio Quondam VISTO: IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO : LQJ1LFROz&DQHSD PROTOCOLLO DATA CODICE PROGETTO NOME FILE REVISIONE SCALA: PROGETTO LIV. PROG. N. PROG. CODICE - DP T O0 5 D 1 6 0 1 ELAB. C B A EMISSIONE A SEGUITO DI RICHIESTA MiTE N. 23984 DEL 8/03/2021 APR 2021 REV. DESCRIZIONE DATA REDATTO VERIFICATO APPROVATO Revised version adopted in Habitat Committee 26.4.2012 ANNEX Form for submission of information to the European Commission according to Art. 6(4) of the Habitats Directive Member State: Italy Date: 13/04/2021 Information to the European Commission according to Article 6(4) of the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) Documentation sent for: information X opinion Art. 6(4).1 Art. 6(4).2 Competent national authority: Ente di gestione Aree Protette Alpi Marittime (Management body for the protected areas of the Maritime Alps) Address: Piazza Regina Elena 30 -12010 Valdieri (CN) Contact person: Tel., fax, e-mail: Tel. +39 0171 976800 Fax +39 0171 976815 [email protected] [email protected] Is the notification containing sensitive information? If yes, please specify and justify 25 1. PLAN OR PROJECT Name of the plan/project: S.S. -

Badalucco Bajardo Bordighera Borgomaro Camporosso Castellaro

Quota di riparto FONDO COMUNI LOCAZIONE 1 Alassio 40,541.92 2 Albenga 24,135.18 3 Albisola Superiore 43,863.12 4 Albissola Marina 16,557.54 5 Altare 5,828.47 6 Ameglia 6,851.26 7 Andora 24,830.85 8 Arcola 7,790.42 9 Arenzano 12,204.19 10 Avegno 4,260.20 11 Badalucco 1,639.64 12 Bajardo 1,108.81 13 Bargagli 9,256.73 14 Bogliasco 9,043.38 15 Boissano 2,689.69 16 Bolano 10,815.32 17 Bonassola 2,353.76 18 Bordighera 10,535.78 19 Borghetto Santo Spirito 19,081.22 20 Borgio Verezzi 5,843.83 21 Borgomaro 1,329.87 22 Bormida 1,333.11 23 Borzonasca 5,402.46 24 Busalla 8,785.86 25 Cairo Montenotte 11,077.47 26 Calice al Cornoviglio 1,697.98 27 Camogli 8,637.26 28 Campo Ligure 6,806.81 29 Campomorone 23,211.64 30 Camporosso 3,253.90 31 Carasco 7,696.77 32 Carcare 14,967.49 33 Casanova Lerrone 2,264.44 34 Casarza Ligure 11,676.99 35 Casella 4,951.43 36 Castellaro 1,297.34 37 Castelnuovo Magra 15,238.75 38 Castiglione Chiavarese 2,537.17 39 Celle Ligure 9,151.19 40 Cengio 6,647.44 41 Ceranesi 5,072.80 42 Ceriale 20,594.14 43 Ceriana 3,878.34 44 Cervo 4,549.89 45 Chiavari 21,748.58 Quota di riparto FONDO COMUNI LOCAZIONE 46 Chiusanico 1,725.70 47 Chiusavecchia 916.26 48 Cicagna 5,832.09 49 Cisano sul Neva 4,624.95 50 Cogoleto 15,522.07 51 Cogorno 14,717.94 52 Cosseria 3,180.16 53 Davagna 3,406.12 54 Deiva Marina 3,210.82 55 Diano Castello 3,311.33 56 Diano Marina 6,292.25 57 Dolceacqua 2,137.06 58 Dolcedo 2,577.13 59 Finale Ligure 57,918.04 60 Follo 7,416.98 61 Framura 1,989.84 62 Garlenda 3,449.93 63 Genova 446,099.43 64 Giustenice 2,902.96 65 Imperia -

The Wolf Population in the Alps: Status and Management

Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/000807 WOLFALPS Wolf in the Alps: implementation of coordinated wolf conservation actions in core areas and beyond Action E8 – Annual thematic conference PROCEEDINGS II CONFERENCE LIFE WOLFALPS The wolf population in the Alps: status and management CUNEO , 22 ND JANUARY 2016 May 2016 Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/000807 WOLFALPS nd Proceedings of the II Conference LIFE WolfAlps - Cuneo 22 January 2016 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Suggested citation: Author of the abstract, Title of the abstract , 2016, in F. Marucco, Proceedings II Conference LIFE WolfAlps – The wolf population in the Alps: status and management, Cuneo 22 nd January 2016, Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/00080 WOLFALPS. Proceedings prepared by F. Marucco, Project LIFE WolfAlps, Centro Gestione e Conservazione Grandi Carnivori, Ente di Gestione delle Aree Protette delle Alpi Marittime. Download is possible at: www.lifewolfalps.eu/documenti/ The II Conference LIFE WolfAlps “The wolf population in the Alps: status and management” has been held in Cuneo on the 22 nd January 2016, at the meeting Center of the Cuneo Province, C.so Dante 41, Cuneo (Italy), and it has been organized in partnership with: Initiative realized thanks to LIFE contribution, a financial instrument of the European Union. Website: www.lifewolfalps.eu 2 Project LIFE 12 NAT/IT/000807 WOLFALPS nd Proceedings of the II Conference LIFE WolfAlps - Cuneo 22 January 2016 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Foreword The Conference LIFE WolfAlps addressed the issue of the natural return of the wolf in the Alps : gave an update on the status of the population in each Alpine country, from France to Slovenia, and discussed the species’ conservation on the long term, also touching the debated topic of its management. -

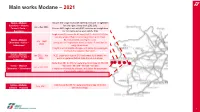

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

Main works Modane – 2021 Torino - Modane Closure 300’ single track with 240’ total closure in nighttime Bussoleno – Modane for two nights every week (S/D, D/L) Jan – Dec 2021 Torino S. Paolo – Closure 240’ single track with 120’ total closure in nigthtime Bussoleno for five nights every week (L/M ÷ V/S) Single track (P) closure for 42 days (26/07 – 06/09/2021) for security works of Exilles and Serra galleries (one track). Torino - Modane No limitation for passengers trains. July – Sept Chiomonte – Exilles – Limitation for freight trains direction Italy – France due to 2021 Salbertrand weight limitations . Freight train timetables changes and delays for passengers trains due to capacity restriction . Torino – Modane Jan 2021 – Apr N.12 single tack closure 240’ each week for 6 weeks for Chiomonte – Exilles – 2021 works on galleries before total closure in Summer Salbertrand Single track (D) for 48h for waterproofing bridge km 58+075 Torino – Modane – 58+ 916 – 58+368 – 60+529 – 60+695 Jun – Oct 2021 Chiomonte – Salbertrand Freight train timetables changes and delays for passengers trains due to capacity restriction . Torino – Modane Total closure for 96h for waterproofing bridge km 8+807 July 2021 Collegno – Avigliana (10-14 /07/2021) 1 Main works Ventimiglia – 2021 Total closure 240’ nighttime for 5 nights every week Genova – Ventimiglia Jan – Dec 2021 for maintenance, infrastructural/technological Savona – Ge. Voltri M. renewal works and works for gauge PC45 in galleries Work on Ansaldo gallery with total closure for 5h for Genova – Ventimiglia Jan – Apr 2021 5 nights every weeks beetween Ge. Sestri and B. -

Tonnare in Italy: Science, History, and Culture of Sardinian Tuna Fishing 1

Tonnare in Italy: Science, History, and Culture of Sardinian Tuna Fishing 1 Katherine Emery The Mediterranean Sea and, in particular, the cristallina waters of Sardinia are confronting a paradox of marine preservation. On the one hand, Italian coastal resources are prized nationally and internationally for their natural beauty as well as economic and recreational uses. On the other hand, deep-seated Italian cultural values and traditions, such as the desire for high-quality fresh fish in local cuisines and the continuity of ancient fishing communities, as well as the demands of tourist and real-estate industries, are contributing to the destruction of marine ecosystems. The synthesis presented here offers a unique perspective combining historical, scientific, and cultural factors important to one Sardinian tonnara in the context of the larger global debate about Atlantic bluefin tuna conservation. This article is divided into four main sections, commencing with contextual background about the Mediterranean Sea and the culture, history, and economics of fish and fishing. Second, it explores as a case study Sardinian fishing culture and its tonnare , including their history, organization, customs, regulations, and traditional fishing method. Third, relevant science pertaining to these fisheries’ issues is reviewed. Lastly, the article considers the future of Italian tonnare and marine conservation options. Fish and fishing in the Mediterranean and Italy The word ‘Mediterranean’ stems from the Latin words medius [middle] and terra [land, earth]: middle of the earth. 2 Ancient Romans referred to it as “ Mare nostrum ” or “our sea”: “the territory of or under the control of the European Mediterranean countries, especially Italy.” 3 Today, the Mediterranean Sea is still an important mutually used resource integral to littoral and inland states’ cultures and trade. -

A Methodology for Assessing the Spatial Distribution of Static Wildfire Risk Over Wide Areas: the Case Studies of Liguria and Sardinia (Italy) 1

A methodology for assessing the spatial distribution of static wildfire risk over wide areas: the case studies of Liguria and Sardinia (Italy) 1 Antonella Bodini, Erika Entrade Institute of Applied Mathematics and Information Technology (CNR-IMATI, Milano), [email protected] Q. Antonio Cossu, Simona Canu Environmental Protection Agency of Sardinia (ARPAS) Paolo Fiorucci, Francesco Gaetani CIMA Research Foundation Ulderica Paroli Regione Liguria, Civil Protection and Emergency Department Abstract : In Mediterranean areas, some studies suggest universal increases in fire frequency due to climatic warming. However, some authors point out that the universality of these results is questionable. In this study, we try to go beyond the simple analysis of statistical data related with the number of fires and the total burned area, which can be misleading in the context of climate change. The fire perimeters have been used to inquire spatialized climate indexes and the vegetation cover. A statistical analysis of climate indexes has been conducted and a certain number of Type of Homogeneous Areas (THA) defined by introducing information on vegetation cover. The comparison of THA and climatic indexes allowed the definition of an index of risk. Maps of this index highlight risky areas in Liguria and Sardinia (Italy). Keywords : climate change, climate indexes, static wildfire risk, vegetation cover. 1. Introduction In Mediterranean area, some studies in the later ’90 (Piñol et al . 1998) predicted a continue increase of the number of days of very high fire risk, and more frequent catastrophic wildfires. Some studies, in the same period, suggested universal increases in fire frequency with climatic warming (Overpeck et al . -

How to Get There Services in the Park

Take nothing how to get there but photographs. Alpi Marittime Nature Park is in the south west Piedmont, on the border between Italy and France, to reach it you get off the Torino-Savona motorway Leave nothing at the Fossano junction and follow the signs for Cuneo and then Borgo San Dalmazzo. The latter is a small town at the junction of three valleys that the marvels of the Maritime Alps but footprints. parks touches. From here you can reach the four villages that play host to the park: Vernante (in Valle Vermenagna), Entracque and Valdieri (Valle Gesso) and Let your memories Aisone (Valle Stura). Vernante is 25 km from Cuneo on the SS.20 Colle di Tenda road, coming from be your souvenirs. the coast it is easier to come up the Roya valley from Ventimiglia through the Colle di Tenda tunnel which brings you out in Vermenagna valley, this is the best way to reach the park from the south. Vernante can also be reached by train on the Torino-Cuneo-Ventimiglia line. Valdieri and Entracque are 18 km and 25 km from Cuneo respectively you follow the SS.20 to Borgo San Dalmazzo, to turn off here for Terme di Valdieri- Entracque. Aisone in the Stura valley is 32 km from Cuneo through Borgo San Dalmazzo along the SS.21 for the Colle della Maddalena road. services in the park office and visitor centres •Valdieri, Director’s office and Administration Piazza Regina Elena, 30 – 12010 Valdieri Sella tel. 0171 97397 – fax 0171 97542 Rio Meris falls towards S.Anna in a string of bubbling Palanfré e-mail: [email protected] – website: www.parcoalpimarittime.it pools and waterfalls. -

Orario Invernale 2020-2021 3ªV Per Biglietteria

RIVIERA TRASPORTI S.p.A. ORARIO INVERNALE 2020-2021 LINEA 12: SANREMO - ARMA DI TAGGIA - IMPERIA - DIANO MARINA - ANDORA e viceversa in vigore dal 14 settembre 2020 Aggiornamento dal 25 gennaio 2021 LV Sc NCC-LV LV NCC-LV LV LV NCC-LV NCC-LV SANREMO 06.15 06.25 06.30 06.40 06.45 06.48 06.50 07.15 07.45 08.00 08.15 08.40 08.45 08.45 09.15 ARMA DI TAGGIA 06.25 06.35 06.45 06.55 07.00 07.03 07.05 07.30 08.00 08.15 08.30 08.55 09.00 09.00 09.30 RIVA LIGURE 06.30 06.40 06.50 07.00 07.05 07.08 07.10 07.35 08.05 08.20 08.35 09.00 09.05 09.05 09.35 SANTO STEFANO 06.32 06.42 06.52 07.02 07.07 07.10 07.12 07.37 08.07 08.22 08.37 09.02 09.07 09.07 09.37 SAN LORENZO 06.40 06.50 07.00 07.05 07.10 07.15 07.18 07.20 07.45 08.15 08.30 08.45 09.10 09.15 09.15 09.45 IMPERIA P.M. 06.50 07.00 07.10 07.15 07.20 07.25 07.28 07.30 07.50 07.55 08.25 08.40 08.55 09.20 09.25 09.25 09.55 IMPERIA ONEGLIA 05.30 06.00 06.25 06.55 07.05 07.20 07.30 07.35 07.38 07.40 08.00 08.05 08.35 08.50 09.05 09.30 09.35 09.35 10.05 DIANO MARINA 05.45 06.15 06.40 07.10 07.35 07.55 08.20 08.50 09.20 09.50 10.20 SAN BARTOLOMEO 05.48 06.18 06.43 07.13 07.38 07.58 08.23 08.53 09.23 09.53 10.23 CERVO 05.50 06.20 06.45 07.15 07.40 08.00 08.25 08.55 09.25 09.55 10.25 ANDORA 05.55 06.25 06.50 07.20 07.50 08.10 08.35 09.05 09.35 10.05 10.35 NCC-LV NCC-LV LV LV LV LV LV NCC-LV NCC-LV SANREMO 09.45 10.15 10.45 10.45 11.15 11.45 12.00 12.15 12.45 13.15 13.45 14.15 ARMA DI TAGGIA 10.00 10.30 11.00 11.00 11.30 12.00 12.15 12.30 13.00 13.30 13.40 14.00 14.30 RIVA LIGURE 10.05 10.35 11.05 11.05 11.35 12.05 12.20 12.35 13.05 13.35 13.45 14.05 14.35 SANTO STEFANO 10.07 10.37 11.07 11.07 11.37 12.07 12.22 12.37 13.07 13.37 13.47 14.07 14.37 SAN LORENZO 10.15 10.45 11.15 11.15 11.45 12.15 12.30 12.45 13.15 13.45 13.55 14.15 14.45 IMPERIA P.M. -

Concorso Ordinario Prospetto Aggregazioni Territoriali ALLEGATO

Concorso ordinario 1 Prospetto aggregazioni territoriali ALLEGATO 2 Regioni responsabili della procedura concorsuale e dove si svolgono le prove Regioni destinatarie delle domande e oggetto di aggregazione A001 - ARTE E IMMAGINE NELLA SCUOLA SECONDARIADI I GRADO CAMPANIA BASILICATA CALABRIA MOLISE PUGLIA SICILIA LAZIO ABRUZZO MARCHE UMBRIA A002 - DESIGN MET.OREF.PIET.DUREGEMME CAMPANIA CALABRIA EMILIA ROMAGNA FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA LAZIO MARCHE SARDEGNA TOSCANA A003 - DESIGN DELLA CERAMICA CAMPANIA CALABRIA A005 - DESIGN DEL TESSUTOE DELLA MODA CAMPANIA PUGLIA SICILIA PIEMONTE FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA TOSCANA LAZIO SARDEGNA A007 - DISCIPLINE AUDIOVISIVE LOMBARDIA FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA LIGURIA PIEMONTE VENETO MARCHE LAZIO SARDEGNA TOSCANA UMBRIA PUGLIA BASILICATA SICILIA A008 - DISCIP GEOM, ARCH, ARRED, SCENOTEC LAZIO ABRUZZO MARCHE SARDEGNA TOSCANA UMBRIA Concorso ordinario 2 Prospetto aggregazioni territoriali ALLEGATO 2 Regioni responsabili della procedura concorsuale e dove si svolgono le prove Regioni destinatarie delle domande e oggetto di aggregazione A008 - DISCIP GEOM, ARCH, ARRED, SCENOTEC LOMBARDIA EMILIA ROMAGNA FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA LIGURIA PIEMONTE VENETO SICILIA BASILICATA CAMPANIA PUGLIA A009 - DISCIP GRAFICHE, PITTORICHE,SCENOG LOMBARDIA EMILIA ROMAGNA LIGURIA PIEMONTE VENETO SICILIA CAMPANIA TOSCANA LAZIO SARDEGNA UMBRIA A010 - DISCIPLINE GRAFICO-PUBBLICITARIE CAMPANIA CALABRIA PUGLIA LAZIO ABRUZZO MARCHE SARDEGNA TOSCANA UMBRIA LOMBARDIA EMILIA ROMAGNA FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA LIGURIA PIEMONTE A011 - DISCIPLINE LETTERARIEE