Maoist Aesthetics in Western Left-Wing Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literacy Practices, Situated Learning and Youth in Nepal's Maoist

104 EBHR-42 Learning in a Guerrilla Community of Practice: Literacy practices, situated learning and youth in Nepal’s Maoist movement (1996-2006) Ina Zharkevich The arts of war are better than no arts at all. (Richards 1998: 24) Young people and conflict, unemployed youth, risk and resiliencehave emerged as key research themes over the past decade or so. The so-called ‘youth bulge theories’ have contributedconsiderably to research on youth and the policy agendas that prioritise the study of youth. It is postulated that the vast numbers of young people in developing countries do not have opportunities for employment and are therefore at risk ofbecoming trouble-makers(see the critique in Boyden 2006). The situation in South Asia might be considered a good example. According tothe World Bank Survey, South Asia has the highest proportion of unemployed and inactive youth in the world (The Economist, 2013).1So, what do young unemployed and inactive people do? Since the category of ‘unemployed youth’ includes people of different class, caste and educa- tional backgrounds, at the risk of oversimplifying the picture,one could argue that some have joined leftist guerrilla movements, while others, especially in India, have filled the rank and file of the Hindu right – either the groups of RSS volunteers (Froerer 2006) or the paramilitaries, such as Salwa Judum (Miklian 2009), who are fighting the Indian Maoists. Both in Nepal and in India, others are in limbo after receiving their degrees, waiting for the prospect of salaried employment whilst largely relying on the political patronage they gained through their membership of the youth wings of various political parties (Jeffrey 2010), which is a common occurrence on university campuses in both India and Nepal (Snellinger 2007). -

Answer: Maoism Is a Form of Communism Developed by Mao Tse Tung

Ques 1: What is Maoism? Answer: Maoism is a form of communism developed by Mao Tse Tung. It is a doctrine to capture State power through a combination of armed insurgency, mass mobilization and strategic alliances. The Maoists also use propaganda and disinformation against State institutions as other components of their insurgency doctrine. Mao called this process, the ‘Protracted Peoples War’, where the emphasis is on ‘military line’ to capture power. Ques 2: What is the central theme of Maoist ideology? Answer: The central theme of Maoist ideology is the use of violence and armed insurrection as a means to capture State power. ‘Bearing of arms is non-negotiable’ as per the Maoist insurgency doctrine. The maoist ideology glorifies violence and the ‘Peoples Liberation Guerrilla Army’ (PLGA) cadres are trained specifically in the worst forms of violence to evoke terror among the population under their domination. However, they also use the subterfuge of mobilizing people over issues of purported inadequacies of the existing system, so that they can be indoctrinated to take recourse to violence as the only means of redressal. Ques 3: Who are the Indian Maoists? Answer: The largest and the most violent Maoist formation in India is the Communist Party of India (Maoist). The CPI (Maoist) is an amalgamation of many splinter groups, which culminated in the merger of two largest Maoist groups in 2004; the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), People War and the Maoist Communist Centre of India. The CPI (Maoist) and all its front organizations formations have been included in the list of banned terrorist organizations under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. -

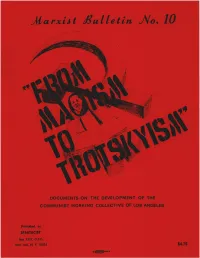

FROM MAOISM to TROTSKYISM -Reprinted from WORKERS VANGUARD, No.1, October 1971

iii PREFACE The Communist Horking Collective originated tvhen a small group of Ivlaoists came together in Los Angeles to undertake an intensive investigation of the history of the communist movement in order to develop a strategy for the U.S. ,socialist revolution. Its study of the essentials of Stalinist and Maoist theory led the CWC to the inescapable conclusion that the theory of IISocialism in One Country" is in irreconcilable opposition to revolutionary internationalism. The consolidation of the CWC around Trotskyism and its systematic study of the various ostensible Trotskyist international tendencies was culminated in the fusion between the CWC and the Spartacist League in September 1971. The brief history of the Ct'lC which appeared originally in the first issue of Workers Vanguard (see page viii) alludes to the splits of the CWC's founding cadre from the Revolutionary Union (RU) and the California Communist League (CCL). To convey the genesis of this process, we have included a number of forerunner documents going back to the original split from the CPUSA on the 50th anniver sary of the October Revolution. The original resignation of comrade~ Treiger and Miller began the "floundering about for three years ••• seeking in Mao Tse Tung Thought a revolutionary al ternati ve to the revisionists." Treiger went on to help found the CWC; fUller con tinued to uphold the dogmatic tradition and declined to even answer the "Letter to a IvIao~_st" (see page 30). Why the Critique of "Tvw Stages"? The lynchpin on which all variants of the fJIaoist "t"t'lO stage" theory of revolution rest--whether applied to the advanced countries or to the colonial world--is collaboration with the ruling class or a section of it during the initial "stage." Early in its develop ment the CWC had rejected the conception as it was applied to the Un1 ted States, but believed it remained applicable to the col'onial revolution. -

Of Concepts and Methods "On Postisms" and Other Essays K

Of Concepts and Methods "On Postisms" and other Essays K. Murali (Ajith) Foreign Languages Press Foreign Languages Press Collection “New Roads” #9 A collection directed by Christophe Kistler Contact – [email protected] https://foreignlanguages.press Paris, 2020 First Edition ISBN: 978-2-491182-39-7 This book is under license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ “Communism is the riddle of history solved, and it knows itself to be this solution.” Karl Marx CONTENTS Introduction Saroj Giri From the October Revolution to the Naxalbari 1 Movement: Understanding Political Subjectivity Preface 34 On Postisms’ Concepts and Methods 36 For a Materialist Ethics 66 On the Laws of History 86 The Vanguard in the 21st Century 96 The Working of the Neo-Colonial Mind 108 If Not Reservation, Then What? 124 On the Specificities of Brahmanist Hindu Fascism 146 Some Semi-Feudal Traits of the Indian Parliamentary 160 System The Maoist Party 166 Re-Reading Marx on British India 178 The Politics of Liberation 190 Appendix In Conversation with the Journalist K. P. Sethunath 220 Introduction Introduction From the October Revolution to the Nax- albari Movement: Understanding Political Subjectivity Saroj Giri1 The first decade since the October Revolution of 1917 was an extremely fertile period in Russia. So much happened in terms of con- testing approaches and divergent paths to socialism and communism that we are yet to fully appreciate the richness, intensity and complexity of the time. In particular, what is called the Soviet revolutionary avant garde (DzigaVertov, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Boris Arvatov) was extremely active during the 1920s. -

Frantz Fanon and the Peasantry As the Centre of Revolution

Chapter 8 Frantz Fanon and the Peasantry as the Centre of Revolution Timothy Kerswell Frantz Fanon is probably better known for his work on decolonization and race, but it would be remiss to ignore his contribution to the debate about social classes and their roles as revolutionary subjects. In this respect, Fanon argued for a position that was part of an influential thought current which saw the peasant at the center of world revolutionary struggles. In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon argued that “It is clear that in the co- lonial countries the peasants alone are revolutionary, for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain. The starving peasant, outside the class system, is the first among the exploited to discover that only violence pays.”1 This statement suggests not only that the peasant would play an important part in liberation and revolutionary struggles, but that they would be the sole revolu- tionary subjects in forthcoming change. Fanon’s attempt to place the peasant at the center was part of a wider cur- rent of thought. This can be seen in the statement of Lin Biao, one of the fore- most thinkers of Maoism who argued, “It must be emphasized that Comrade Mao Tse-tung’s theory of the establishment of rural revolutionary base areas and the encirclement of the cities from the countryside is of outstanding and universal practical importance for the present revolutionary struggles of all the oppressed nations and peoples, and particularly for the revolutionary struggles of the oppressed nations and peoples in Asia, Africa and Latin America against imperialism and its lackeys.”2 It was this theorization that “turn[ed] the image of the peasantry upside down,”3 especially from Marx’s previous assessment that peasants constituted a “sack of potatoes”4 in terms of their revolutionary class-consciousness. -

The Nepalese Maoist Movement in Comparative Perspective: Learning from the History of Naxalism in India

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 23 Number 1 Himalaya; The Journal of the Article 8 Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 2003 The Nepalese Maoist Movement in Comparative Perspective: Learning from the History of Naxalism in India Richard Bownas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Bownas, Richard. 2003. The Nepalese Maoist Movement in Comparative Perspective: Learning from the History of Naxalism in India. HIMALAYA 23(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol23/iss1/8 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD BowNAS THE NEPALESE MAOIST MovEMENT IN CoMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: LEARNIN G FROM THE H ISTORY OF NAXALISM IN INDIA This paper compares the contemporary Maoist movement in Nepal with the Naxalite movemelll in India, from 1967 to the present. The paper touches on three main areas: the two movemems' ambiguous relationship to ethnicity, the hi stories of prior 'traditional' m obilization that bo th move ments drew on, and the relationship between vanguard and mass movement in both cases. The first aim of the paper is to show how the Naxalite movemem has transformed itself over the last 35 years and how its military tacti cs and organizational· form have changed . I then ask whether Nepal's lvla o ists more closely resemble the earli er phase of Naxali sm , in which the leadership had broad popular appeal and worked closely with its peasant base, o r its later phase, in which the leadership became dise ngaged fr om its base and adopted urban 'terror' tactics. -

Mao on Investigation and Research

Intra-party document Zhongfa [1961] No. 261 Do not lose [A complete translation into English of] Mao Zedong on Investigation and Research Central Committee General Office Confidential Office print. 4 April 1961 (CCP Hebei Provincial Committee General Office reprint.) 15 April 1961 Notification This collection of texts is an intra-Party document distributed to the county level in the civilian local sector, to the regiment level in the armed forces, and to the corresponding level in other sectors. It is meant to be read by cadres at or above the county/regiment level. For convenience’s sake, we only print and forward sample copies. We expect the total number of copies needed by the cadres at the designated levels to be printed up and distributed by the Party committees of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, by the [PLA] General Political Department, by the Party committee of the organs immediately subordinate to the [Party] Centre, and by the Party committee of the central state organs. Please do not reproduce this collection in Party journals. Central Committee General Office 4 April 1961 2 Contents Page On Investigation Work (Spring of 1930) 5 Appendix: Letter from the CCP Centre to the Centre’s Regional Bureaus and the Party Committees of the Provinces, Municipalities, and [Autonomous] Regions Concerning the Matter of Conscientiously Carrying out Investigations (23 March 1961) 13 Preface to Rural Surveys (17 March 1941) 15 Reform Our Study (May 1941) 18 Appendix: CCP Centre Resolution on Investigation and Research (1 -

Antagonistic and Non-Antagonistic Contradictions by Ai Siqi

Antagonistic and Non-Antagonistic Contradictions by Ai Siqi This is a selection from Ai Siqi's book Lecture Outline on Dialectical Materialism, Beijing, 1957. This book was translated into a number of languages. The selection describes the concept of non‐antagonistic contradiction as expounded in several works by Mao Zedong. This translation is based Chinese text published in Ai Siqi's Complete Works [艾思奇全书], Beijing: People's publishing House, 2006, vol. 6, pp. 832‐836. [832] 5. Antagonistic and non-antagonistic forms of struggle The struggle of opposites is encountered in our work. It cannot use one absolute, but this principle does not at all fixed kind of form and tie itself to one rigid exclude diversity of struggle forms and method, and in this way, it is possible to methods of resolution. On the contrary, grasp revolution in a comparatively forms of struggle and methods of resolving successful way, and lead towards victory. contradictions must have various For example, in order to eliminate manifestations, depending on the quality of capitalism, our Chinese method is not to the contradiction and all kinds of different use a form of great force to expropriate the circumstances. One of the characteristics of means of production, but mainly to adopt formalism 1 is to grasp some one kind of the form of peaceful remolding to redeem struggle form and method of resolving them. contradictions in a one-sided way, and In the various sorts and varieties of regard it as a thing which is absolutely struggle forms, two different forms of impossible to change, thus committing struggle should be especially studied, subjectivist errors. -

Althusser-Mao” Problematic and the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism: Maoism, China and Althusser on Ideology

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 20 (2018) Issue 3 Article 6 The “Althusser-Mao” Problematic and the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism: Maoism, China and Althusser on Ideology Fang Yan the School of Chinese Language and Literature, South China Normal University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Chinese Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Yan, Fang. "The “Althusser-Mao” Problematic and the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism: Maoism, China and Althusser on Ideology." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 20.3 (2018): <https://doi.org/10.7771/ 1481-4374.3258> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

A Study of the Relationship Between the Black Panther Party and Maoism

Constructing the Past Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 7 August 2009 “Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism Chao Ren Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Ren, Chao (2009) "“Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism," Constructing the Past: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol10/iss1/7 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. “Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism This article is available in Constructing the Past: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol10/iss1/7 28 Chao Ren “Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism Chao Ren “…the most essential thing in Marxism, the living soul of Marxism, is the concrete analysis of concrete conditions.” — Mao Zedong, On Contradiction, April 1937 Late September, 1971. -

Protracted People's War Is Not a Universal Strategy for Revolution

Protracted People’s War is Not a Universal Strategy for Revolution 2018-01-19 00:42:22 -0400 Protracted People’s War (PPW) has been promoted as a universal strategy for revolution in recent years despite the fact that this directly contradicts Mao’s conclusions in his writing on revolutionary strategy. Mao emphasized PPW was possible in China because of the semi-feudal nature of Chinese society, and because of antagonistic divisions within the white regime which encircled the red base areas. Basic analysis shows that the strategy cannot be practically applied in the U.S. or other imperialist countries. Despite this, advocates for the universality of PPW claim that support for their thesis is a central principle of Maoism. In this document we refute these claims, and outline a revolutionary strategy based on an analysis of the concrete conditions of the U.S. state. In our view, confusion on foundational questions of revolutionary strategy, and lack of familiarity with Mao’s writings on the actual strategy of PPW, has led to the growth of dogmatic and ultra-“left” tendencies within the U.S. Maoist movement. Some are unaware of the nature of the struggle in the Chinese Com- munist Party (CCP) against Wang Ming, Li Lisan, and other dogmatists. As a result, they conflate Mao’s critique of an insurrectionary strategy in China with a critique of insurrection as a strategy for revolution in general. Some advocate for the formation of base areas and for guerrilla warfare in imperialist coun- tries, while others negate PPW as a concrete revolutionary strategy, reducing it to an abstract generality or a label for focoist armed struggle. -

Critique of Maoist Reason

Critique of Maoist Reason J. Moufawad-Paul Foreign Languages Press Foreign Languages Press Collection “New Roads” #5 A collection directed by Christophe Kistler Contact – [email protected] https://foreignlanguages.press Paris 2020 First Edition ISBN: 978-2-491182-11-3 This book is under license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Route Charted to Date 7 Chapter 2 Thinking Science 19 Chapter 3 The Maoist Point of Origin 35 Chapter 4 Against Communist Theology 51 Chapter 5 The Dogmato-eclecticism of “Maoist Third 69 Worldism” Chapter 6 Left and Right Opportunist Practice 87 Chapter 7 Making Revolution 95 Conclusion 104 Acknowledgements 109 Introduction Introduction In the face of critical passivity and dry formalism we must uphold our collective capacity to think thought. The multiple articulations of bourgeois reason demand that we accept the current state of affairs as natural, reducing critical thinking to that which functions within the boundaries drawn by its order. Even when we break from the diktat of this reason to pursue revolutionary projects, it is difficult to break from the way this ideological hegemony has trained us to think from the moment we were born. Since we are still more-or-less immersed in cap- italist culture––from our jobs to the media we consume––the training persists.1 Hence, while we might supersede the boundaries drawn by bourgeois reason, it remains a constant struggle to escape its imaginary. The simplicity encouraged by bourgeois reasoning––formulaic repeti- tion, a refusal to think beneath the appearance of things––thus finds its way into the reasoning of those who believe they have slipped its grasp.