Of Concepts and Methods "On Postisms" and Other Essays K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anuradha Ghandy Edito Da Movimento Femminista Proletario Rivoluzionario

Tendenze filosofiche nel Movimento Femminista Anuradha Ghandy Edito da Movimento Femminista Proletario Rivoluzionario Dicembre 2018 [email protected] SOMMARIO Prefazione Introduzione Visione sul movimento delle donne in occidente Il Femminismo liberale Critica Il Femminismo radicale Sesso-genere e patriarcato Sessualità: eterosessualità e lesbismo Critica Anarco-Femminismo L’Eco-Femminismo Il Femminismo socialista Strategia Femminista-Socialista per la liberazione delle donne Critica Post-Modernismo e Femminismo Per riassumere PREFAZIONE “ … Ma Anuradha era differente...” Arundathy Roy Questo è quello che tutti quelli che conoscevano Anuradha Ghandy dicono. Questo è ciò che quasi tutti la cui vita è stata da lei toccata pensano. È morta in un ospedale di Mumbai la mattina del 12 aprile 2008, di malaria. Probabilmente l’aveva contratta nella giungla in Jharkhand, dove con duceva lezioni di studio a un gruppo di donne Adivasi. In questa nostra grande democrazia, Anuradha Ghandy era conosciuta come una “terrorista maoista”, suscettibile di essere arrestata o, più probabilmente, sparata in un falso “incontro”, come lo sono stati centinaia di suoi compagni. Quando questa terrorista ha avuto la febbre alta e si è recata in ospedale per sottoporsi al test del sangue, ha lasciato un nome e numero di telefono falsi al dotto- re che la stava curando. Quindi non riuscì a raggiungerla per dirle che i test mostrarono che lei aveva la malaria falciparum potenzial- mente fatale. Gli organi di Anuradha cominciarono a disfarsi, uno per uno. Quando fu ricoverata all’ospedale l’11 aprile, era troppo tardi. E così, in questo modo del tutto inutile, l’abbiamo persa. Aveva 54 anni quando morì e aveva passato più di 30 anni della sua vita, la maggior parte di essi in clandestinità, come una rivolu- zionaria di professione. -

Paper Teplate

Volume-05 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-04 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary April -2020 www.rrjournals.com[Peer Reviewed Journal] Analysis of reflection of the Marxist Cultural Movement (1940s) of India in Contemporary Periodicals Dr. Sreyasi Ghosh Assistant Professor and HOD of History Dept., Hiralal Mazumdar Memorial College for Women, Dakshineshwar, Kolkata- 700035 (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History In this study I have tried my level best to show how the Marxist Cultural Movement ( Published Online: 16 Apr 2020 1940s) of Bengal/ India left its all-round imprint on contemporary periodicals such as Parichay, Agrani, Arani, Janayuddha, Natun Sahitya, Kranti, Sahityapatra etc. That Keywords movement was generated in the stormy backdrop of the devastating Second World Anti- Fascist, Communist Party, Marxism, War, famine, communal riots with bloodbath, and Partition of india. Undoubtedly the Progressive Literature, Social realism. Communist Party of India gave leadership in this cultural renaissance established on social realism but renowned personalities not under the umbrella of the Marxist *Corresponding Author Email: sreyasighosh[at]yahoo.com ideology also participated and contributed a lot in it which influenced contemporary literature, songs, painting, sculpture, dance movements and world of movie- making. Organisations like the All-India Progressive Writers” Association( 1936), Youth Cultural Institute ( 1940), Association of Friends of the Soviet Union (1941), Anti- Fascist Writers and Artists” Association ( 1942) and the All- India People”s Theatre Association (1943) etc emerged as pillars of that movement. I.P.T.A was nothing but a very effective arm of the Pragati Lekhak Sangha, which was created mainly for flourishing talent of artists engaged with singing and drama performances. -

SO&Ltlijamltlttr

a~r~~to~as~ra• SO<liJAMltltTr -NEWS RELEASE- REVOLUT ION IS THE MAIN TREND IN THE WORlD TODAY 9-12-72 ' ' AFRO-ASIAN SOLIDARITY News Release is produced by AFRO-ASIAN PEOPLE'S SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT. It is distributed free to members and supporters. Donations & enquiries may be sent to: AAPSM. P.O.BOX 712. LONDON SW17 2EU RED SALUTE TO THE . GREAT . INDIAN PEOPLE ' S l-IBERATION ARNY ! Statement of the Indian Progressive Study Group (England), commemorating the 2nd Anniversary of the formation of the great Indian People ' s Liberation Army , December 7 1 1972. DeccGber 7, 1972 marks the second anniversary of the formation of the great Indian Pl~CPLE'S LI:iLHATION Am,y (PLA) under tlle leadership of the great Cornr.JUnist Party of India (K-L) and the great leader and helmsman of Indian Revolution, res pected nnd beloved Comrade Charu Mazumdar . Armed struggle started in India with the clap of sprinG thunder of Naxalbari in 1967 personally led by Comrade Charu Kazumdar . Ever since then , this single sparl: hc.s created n prairie fire of the armed agrarian revolution in all l)o.rts of India, leadins to the formation of the great Communist Party of India (H-L) on April 22 1 1969 and to the Historic 8th Congress (First since tkxalbari) of the C6mmunist Party of India (M-L) in May 1970. From the platform of this historic Party Congress Comrade Charu Mazumdar said: 11 It is sure the Red Army can be created not only in Srikakulam but also in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh , Bihar ancl ·.Jest Bengal. -

Literacy Practices, Situated Learning and Youth in Nepal's Maoist

104 EBHR-42 Learning in a Guerrilla Community of Practice: Literacy practices, situated learning and youth in Nepal’s Maoist movement (1996-2006) Ina Zharkevich The arts of war are better than no arts at all. (Richards 1998: 24) Young people and conflict, unemployed youth, risk and resiliencehave emerged as key research themes over the past decade or so. The so-called ‘youth bulge theories’ have contributedconsiderably to research on youth and the policy agendas that prioritise the study of youth. It is postulated that the vast numbers of young people in developing countries do not have opportunities for employment and are therefore at risk ofbecoming trouble-makers(see the critique in Boyden 2006). The situation in South Asia might be considered a good example. According tothe World Bank Survey, South Asia has the highest proportion of unemployed and inactive youth in the world (The Economist, 2013).1So, what do young unemployed and inactive people do? Since the category of ‘unemployed youth’ includes people of different class, caste and educa- tional backgrounds, at the risk of oversimplifying the picture,one could argue that some have joined leftist guerrilla movements, while others, especially in India, have filled the rank and file of the Hindu right – either the groups of RSS volunteers (Froerer 2006) or the paramilitaries, such as Salwa Judum (Miklian 2009), who are fighting the Indian Maoists. Both in Nepal and in India, others are in limbo after receiving their degrees, waiting for the prospect of salaried employment whilst largely relying on the political patronage they gained through their membership of the youth wings of various political parties (Jeffrey 2010), which is a common occurrence on university campuses in both India and Nepal (Snellinger 2007). -

No.108 of 2000 (Sbsinha and Ppnaolekar,JJ.,) 23.0

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Nair Service Society Vs. State of Kerala C.P.(Civil)No.108 of 2000 (S.B.Sinha and P.P.Naolekar,JJ.,) 23.02.2007 JUDGMENT S.B.Sinha,J., 1.In these petitions, interpretation of this Court's judgment as regards identification of 'creamy layer' amongst the backward classes and their exclusion from the purview of reservation, vis-`-vis, the report of Justice K.K. Narendran Commission (hereinafter referred to as 'Narendran Commission') and acceptance thereof by the State of Kerala in issuing the impugned notification dated 27.5.2000, falls for our consideration in this writ petition by the Nair Service Society ('the Society'), a Society which was initially registered under Section 26 of the Travancore Companies Act, 1914 and after coming into force the Companies Act, 1956, it would be deemed to have been registered under Section 25 thereof. The objects of the Society are said to be : “(i) to remove the difference prevailing from places to places amongst Nairs in their social customs and usages as well as the unhealthy practices prevalent among them; (ii) to participate in the efforts of other communities for the betterment of their lot and to maintain and foster communal amity; (iii) to work for the uplift of the depressed classes; (iv) to start and maintain such institutions as are found necessary to promote the objects of the society. It is not in dispute that it had filed a writ petition before the Kerala High Court questioning the validity of the report commonly known as Mandal Commission Report. -

The Official Organ of KPA, Mumbai

RNI Registration No. MAHMUL/2004/13413 Price: ` 30.00 Vol. VI, No. 4 : July-August 2011 ilchar MThe Official Organ of KPA, Mumbai Chakreshvara Sharika [Painting by Dr. C.L.Raina, Miami, USA] In this issue Ø Message from the President l Between Ourselves - Rajen Kaul Page 2 Milchar Ø Editorial Official Organ of l Rehabilitation of KPs Kashmiri Pandits' Association - T.N.Dhar 'Kundan' Page 3 Mumbai Ø kçÀçJ³ç l iç]pçuç (Regd. Charitable Trust - Regn. No. A-2815 BOM) - Òçícç vççLç kçÀçÌuç `Dçhç&Cç' Page 4 Ø Donations for Sharada Sadan Page 5 Websites: www.kpamumbai.org.in Ø ÞççÇ cçnçjç%ççÇ ®ççuççÇmçç Page 8 www.ikashmir.net/milchar/index.html Ø Report & Biradari News Page 9 E-Mail: [email protected] Ø DçHçÀmççvçe Vol. VI ~ No. 4 l yçíçÆs yçlçe - [ç. jçíMçvç mçjçHçÀ `jçíçÆMç jçíçÆMç' Page 13 EDITORIAL BOARD Ø KPs' Resettlement Issues l An Interview with Mr. Moti Kaul - Interviewer P.N.Wali Page 14 Editor :M.K.Raina Ø Between the Lines Associate Editor :S.P.Kachru l The Musings Members :S.K.Kaul - S.K.Kaul Page 16 Chand Bhat Ø kçÀçJ³ç Consulting Editors :P.N.Wali l jçlçe®ç lçvnç@³ççÇ T.N.Dhar ‘Kundan’ - [ç. yççÇ.kçÀí.cççí]pçç Page 17 Ø Culture & Heritage Webmasters :Sunil Fotedar, USA l Influence of Advaita on Muslim Rishis of Kashmir - Part 4 K.K.Kemmu - T.N.Dhar 'Kundan' Page 18 Naren Kachroo Ø DçHçÀmççvçe Business Manager :Sundeep Raina l hçÓMçáKç çÆlç vç³ç, æ®ççôuçáKç çÆlç vçç? Circulation Managar :Neena Kher - Ëo³çvççLç kçÀçÌuç `çEjo' Page 22 Ø Requiem l On a Friend's Demise Yearly Subscription : ` 250.00 - Dr. -

Mao on Investigation and Research

Intra-party document Zhongfa [1961] No. 261 Do not lose [A complete translation into English of] Mao Zedong on Investigation and Research Central Committee General Office Confidential Office print. 4 April 1961 (CCP Hebei Provincial Committee General Office reprint.) 15 April 1961 Notification This collection of texts is an intra-Party document distributed to the county level in the civilian local sector, to the regiment level in the armed forces, and to the corresponding level in other sectors. It is meant to be read by cadres at or above the county/regiment level. For convenience’s sake, we only print and forward sample copies. We expect the total number of copies needed by the cadres at the designated levels to be printed up and distributed by the Party committees of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, by the [PLA] General Political Department, by the Party committee of the organs immediately subordinate to the [Party] Centre, and by the Party committee of the central state organs. Please do not reproduce this collection in Party journals. Central Committee General Office 4 April 1961 2 Contents Page On Investigation Work (Spring of 1930) 5 Appendix: Letter from the CCP Centre to the Centre’s Regional Bureaus and the Party Committees of the Provinces, Municipalities, and [Autonomous] Regions Concerning the Matter of Conscientiously Carrying out Investigations (23 March 1961) 13 Preface to Rural Surveys (17 March 1941) 15 Reform Our Study (May 1941) 18 Appendix: CCP Centre Resolution on Investigation and Research (1 -

Antagonistic and Non-Antagonistic Contradictions by Ai Siqi

Antagonistic and Non-Antagonistic Contradictions by Ai Siqi This is a selection from Ai Siqi's book Lecture Outline on Dialectical Materialism, Beijing, 1957. This book was translated into a number of languages. The selection describes the concept of non‐antagonistic contradiction as expounded in several works by Mao Zedong. This translation is based Chinese text published in Ai Siqi's Complete Works [艾思奇全书], Beijing: People's publishing House, 2006, vol. 6, pp. 832‐836. [832] 5. Antagonistic and non-antagonistic forms of struggle The struggle of opposites is encountered in our work. It cannot use one absolute, but this principle does not at all fixed kind of form and tie itself to one rigid exclude diversity of struggle forms and method, and in this way, it is possible to methods of resolution. On the contrary, grasp revolution in a comparatively forms of struggle and methods of resolving successful way, and lead towards victory. contradictions must have various For example, in order to eliminate manifestations, depending on the quality of capitalism, our Chinese method is not to the contradiction and all kinds of different use a form of great force to expropriate the circumstances. One of the characteristics of means of production, but mainly to adopt formalism 1 is to grasp some one kind of the form of peaceful remolding to redeem struggle form and method of resolving them. contradictions in a one-sided way, and In the various sorts and varieties of regard it as a thing which is absolutely struggle forms, two different forms of impossible to change, thus committing struggle should be especially studied, subjectivist errors. -

Althusser-Mao” Problematic and the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism: Maoism, China and Althusser on Ideology

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 20 (2018) Issue 3 Article 6 The “Althusser-Mao” Problematic and the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism: Maoism, China and Althusser on Ideology Fang Yan the School of Chinese Language and Literature, South China Normal University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Chinese Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Yan, Fang. "The “Althusser-Mao” Problematic and the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism: Maoism, China and Althusser on Ideology." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 20.3 (2018): <https://doi.org/10.7771/ 1481-4374.3258> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

A Study of the Relationship Between the Black Panther Party and Maoism

Constructing the Past Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 7 August 2009 “Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism Chao Ren Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Ren, Chao (2009) "“Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism," Constructing the Past: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol10/iss1/7 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. “Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism This article is available in Constructing the Past: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol10/iss1/7 28 Chao Ren “Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism Chao Ren “…the most essential thing in Marxism, the living soul of Marxism, is the concrete analysis of concrete conditions.” — Mao Zedong, On Contradiction, April 1937 Late September, 1971. -

Searchable PDF Format

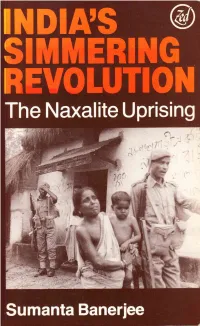

lndia's Simmering Revolution Sumanta Banerjee lndia's Simmeri ng Revolution The Naxalite Uprising Sumanta Banerjee Contents India's Simmering Revolution was first published in India under the title In the llake of Naxalbari: A History of the Naxalite Movement lVlirps in India by Subarnarekha, 73 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Calcutta 700 1 009 in 1980; republished in a revised and updated edition by Zed lrr lr<lduction Books Ltd., 57 Caledonian Road, London Nl 9BU in 1984. I l'lrc Rural Scene I Copyright @ Sumanta Banerjee, 1980, 1984 I lrc Agrarian Situationt 1966-67 I 6 Typesetting by Folio Photosetting ( l'l(M-L) View of Indian Rural Society 7 Cover photo courtesy of Bejoy Sen Gupta I lrc Government's Measures Cover design by Jacque Solomons l lrc Rural Tradition: Myth or Reality? t2 Printed by The Pitman Press, Bath l't'lrstnt Revolts t4 All rights reserved llre Telengana Liberation Struggle 19 ( l'l(M-L) Programme for the Countryside 26 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Banerjee, Sumanta ' I'hc Urban Scene 3l India's simmering revolution. I lrc Few at the ToP JJ l. Naxalite Movement 34 I. Title I lro [ndustrial Recession: 1966-67 JIa- 322.4'z',0954 D5480.84 I lre Foreign Grip on the Indian Economy 42 rsBN 0-86232-038-0 Pb ( l'l(M-L) Views on the Indian Bourgeoisie ISBN 0-86232-037-2 Hb I lrc Petty Bourgeoisie 48 I lro Students 50 US Distributor 53 Biblio Distribution Center, 81 Adams Drive, Totowa, New Jersey l lrc Lumpenproletariat 0'1512 t lhe Communist Party 58 I lrc Communist Party of India: Before 1947 58 I lrc CPI: After 1947 6l I lre Inner-Party Struggle Over Telengana 64 I he CPI(M) 72 ( 'lraru Mazumdar's Theories 74 .l Nlxalbari 82 l'lre West Bengal United Front Government 82 Itcginnings at Naxalbari 84 Assessments Iconoclasm 178 The Consequences Attacks on the Police 182 Dissensions in the CPI(M) Building up the Arsenal 185 The Co-ordination Committee The Counter-Offensive 186 Jail Breaks 189 5. -

Contextualising Dalit Women's Voices: a Study of Urmila Pawar and Bama's Autobiographies

International Journal of Applied Research 2021; 7(5): 389-392 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Contextualising Dalit women’s voices: A study of Impact Factor: 8.4 IJAR 2021; 7(5): 389-392 Urmila Pawar and Bama’s autobiographies www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 04-03-2021 Accepted: 15-04-2021 Praveshika Mishra Praveshika Mishra Assistant Professor, Abstract Department of English, Mata Since the beginning of resistance against patriarchy, women’s issues have become an integral part of Sundri College for Women, public sphere globally. This has been possible due to their constant struggle to understand their own University of Delhi, New agency that women have got their due representation. However, the issue of Dalit women’s Delhi, India representation has not effectively managed to be heard and losing its sheen as it lacks agency owing to the homogenisation of their experiences with the elite ones. In this regard, an independent and autonomous assertion of Dalit women has emerged possibly through writings, particularly; life narratives. Therefore, various Dalit women writers viz. Baby Kamble, Urmila Pawar, Bama, Gogu Shyamala and others have started registering their presence in the literary world through autobiographies, memoirs, narratives etc. Dalit women writers audaciously expose the society which has objectified them, abused them and stripped them off their identity and has effectively maintained patronising stance. The present article aims to study and analyse the Dalit representation/ voices through Dalit women autobiographies namely Urmila Pawar’s The Weave of My Life: A Dalit Woman’s Memoirs and Bama’s Karukku. Keywords: Patriarchy, agency, autonomous assertion, Dalit women writers, patronising stance Introduction Dalit life writing is an emerging field wherein a writer as an agent expresses various dimensions of oppression through literary means viz.