Living with Or Beside the River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED for the POST of GD. IV of AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT of DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR

LIST OF ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF GD. IV OF AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR Date of form Sl Post Registration No Candidate Name Father's Name Present Address Mobile No Date of Birth Submission 1 Grade IV 101321 RATUL BORAH NAREN BORAH VILL:-BORPATHAR NO-1,NARAYANPUR,GOSAIBARI,LAKHIMPUR,Assam,787033 6000682491 30-09-1978 18-11-2020 2 Grade IV 101739 YASHMINA HUSSAIN MUZIBUL HUSSAIN WARD NO-14, TOWN BANTOW,NORTH LAKHIMPUR,KHELMATI,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 6002014868 08-07-1997 01-12-2020 3 Grade IV 102050 RAHUL LAMA BIKASH LAMA 191,VILL NO 2 DOLABARI,KALIABHOMORA,SONITPUR,ASSAM,784001 9678122171 01-10-1999 26-11-2020 4 Grade IV 102187 NIRUPAM NATH NIDHU BHUSAN NATH 98,MONTALI,MAHISHASAN,KARIMGANJ,ASSAM,788781 9854532604 03-01-2000 29-11-2020 5 Grade IV 102253 LAKHYA JYOTI HAZARIKA JATIN HAZARIKA NH-15,BRAHMAJAN,BRAHMAJAN,BISWANATH,ASSAM,784172 8638045134 26-10-1991 06-12-2020 6 Grade IV 102458 NABAJIT SAIKIA LATE CENIRAM SAIKIA PANIGAON,PANIGAON,PANIGAON,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787052 9127451770 31-12-1994 07-12-2020 7 Grade IV 102516 BABY MISSONG TANKESWAR MISSONG KAITONG,KAITONG ,KAITONG,DHEMAJI,ASSAM,787058 6001247428 04-10-2001 05-12-2020 8 Grade IV 103091 MADHYA MONI SAIKIA BOLURAM SAIKIA Near Gosaipukhuri Namghor,Gosaipukhuri,Adi alengi,Lakhimpur,Assam,787054 8011440485 01-01-1987 07-12-2020 9 Grade IV 103220 JAHAN IDRISH AHMED MUKSHED ALI HAZARIKA K B ROAD,KHUTAKATIA,JAPISAJIA,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 7002409259 01-01-1988 01-12-2020 10 Grade IV 103270 NIHARIKA KALITA ARABINDA KALITA 006,GUWAHATI,KAHILIPARA,KAMRUP -

The Flood Situation of Assam – a Case Study

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264878734 The Flood Situation of Assam – A Case Study Article CITATION READS 1 34,158 2 authors, including: Mukul Bora Dibrugarh University 10 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Mukul Bora on 31 October 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Flood Situation of Assam – A Case Study Mukul Chandra Bora Lecturer (Sélection Grade) in Civil Engineering Dibrugarh Polytechnic, Lahowal: Pin: 786010 Assam, India Abstract The problem caused by water may broadly be catagorised into two major groups’ viz. shortage of water and surplus of water. Shortage of water causes drought and surplus water causes flood. The water is the vital ingredients for the survival of human being but sometimes it may cause woe to the human life not due to insufficient water but due to abundant water which in turn causes the natural disaster called as flood. Assam is situated at the easternmost part of India. Geographically it is at the foothills of the Himalaya. Every year Assam experiences a huge amount of losses due to devastating flood caused by the river Brahmaputra. The losses are more in few places like (Majuli, the biggest river Island), Dhemaji, North Lakhimpur, Dhakuakhana and few places of Barak valley in Assam. The problem of flood is very old in Assam and the solution is very much difficult due to complex and devastating nature of the River Brahmaputra. Both short term and long term measures are sometimes failed to mitigate the losses caused by flood. -

Seasonal Variation of Drinking Water Quality with Respect to Fluoride and Nitrate in Dhakuakhana Sub-Division of Lakhimpur Distr

Int. J. Chem. Sci.: 7(3), 2009, 1821-1830 SEASONAL VARIATION OF DRINKING WATER QUALITY WITH RESPECT TO FLUORIDE AND NITRATE IN DHAKUAKHANA SUB-DIVISION OF LAKHIMPUR DISTRICT OF ASSAM JAYANTA CHUTIA ∗∗∗ and SIBA PRASAD SARMA a Department of Chemistry, Brahmaputra Valley Academy, Khelmati, NORTH LAKHIMPUR - 787 031 (Assam) INDIA aDepartment of Chemistry, Lakhimpur Girls’ College, NORTH LAKHIMPUR - 787 031 (Assam) INDIA ABSTRACT The present investigation has been undertaken to determine the seasonal variation of the quality of drinking water of the study area Thirty water samples were analysed during May-June 2008 for pH , total hardness, fluoride and nitrate contents by adopting standard methods (APHA-AWWA-WPCF , 1995) and another thirty water samples were analysed during Nov-Dec. 2008 for the same contents. The data obtained were within the standard, permissible limits of WHO. The variations of the pH values were not vary large but an increase was noticeable during winter and a lowering during the post monsoon period. All the water samples were found either soft or moderately hard. The total hardness values were comparatively higher in the water samples collected during the dry season. Fluoride and nitrate contents were found slightly higher during post-monsoon period. Key words : pH, Hardness, Fluoride, Nitrate INTRODUCTION The environment for any living organism has never been constant or static . Comprising over 71% earth’s surface, water is unquestionably the most precious natural resource that exists on our planet 1. Although water is very abundant on this earth, yet it is very precious. Out of the total water reserves of the world, about 97% is salty water (Marine) and only 3% is freshwater. -

Conservation of Gangetic Dolphin in Brahmaputra River System, India

CONSERVATION OF GANGETIC DOLPHIN IN BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER SYSTEM, INDIA Final Technical Report A. Wakid Project Leader, Gangetic Dolphin Conservation Project Assam, India Email: [email protected] 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There was no comprehensive data on the conservation status of Gangetic dolphin in Brahmaputra river system for last 12 years. Therefore, it was very important to undertake a detail study on the species from the conservation point of view in the entire river system within Assam, based on which site and factor specific conservation actions would be worthwhile. However, getting the sponsorship to conduct this task in a huge geographical area of about 56,000 sq. km. itself was a great problem. The support from the BP Conservation Programme (BPCP) and the Rufford Small Grant for Nature Conservation (RSG) made it possible for me. I am hereby expressing my sincere thanks to both of these Funding Agencies for their great support to save this endangered species. Besides their enormous workload, Marianne Dunn, Dalgen Robyn, Kate Stoke and Jaimye Bartake of BPCP spent a lot of time for my Project and for me through advise, network and capacity building, which helped me in successful completion of this project. I am very much grateful to all of them. Josh Cole, the Programme Manager of RSG encouraged me through his visit to my field area in April, 2005. I am thankful to him for this encouragement. Simon Mickleburgh and Dr. Martin Fisher (Flora & Fauna International), Rosey Travellan (Tropical Biology Association), Gill Braulik (IUCN), Brian Smith (IUCN), Rundall Reeves (IUCN), Dr. A. R. Rahmani (BNHS), Prof. -

Kati Bihu’ Among the Major Tribes of Lakhimpur District of Assam

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 Understanding the Different Rites and Rituals of ‘Kati Bihu’ among the major Tribes of Lakhimpur District of Assam. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dr. Montu Chetia Department of History, Kampur College, Nagaon, Assam - 782426 Gmail ID: [email protected] Phone: 9101093556 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Volume 8, Issue 9, 2020 http://aegaeum.com/ Page No: 555 AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 Understanding the Different Rites and Rituals of ‘Kati Bihu’ among the Major Tribes of Lakhimpur District of Assam. Dr. Montu Chetia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Bihu is a national festival of Assam celebrated by all sections of the society irrespective of caste, creed and religion. The Bihu is the identity of Assamese people in all over the country. It is also the symbol of unity among the people of the state. There are three kinds of Bihu generally observed in Assam- Bohag Bihu or Rongali Bihu, Magh Bihu or Bhogali Bihu and Kati Bihu or Kongali Bihu. Every Bihu has its own features and characteristics which have enriched the cultural prosperity of Assam as well as the whole north eastern region . On the other hand although Bihu is the national festival of Assam yet it varies in form from place to place which have developed the cultural diversity of the state. This paper is an attempt to understand the different rites and rituals of the Kati Bihu or Kongali Bihu among the various tribes of Lakhimpur district as well as whole north bank area of upper Assam and their changes and continuity. KEY WORDS: Kati Bihu, rites and rituals, changes and continuity -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Introduction: Culture is the soul as well as identity of a society. -

Honourable Speaker Sir, I Rise to Present the Budget Estimates for The

Honourable Speaker Sir, I rise to present the budget estimates for the financial year 2012-13. 1. Economic environment : 1.1 Before I proceed to present my budget proposals, I would like to apprise the Honourable Members of this august House about the overall economic environment and financial position of the State. 1.2 The growth rate of GSDP in the State during the 9 th Plan period was 1.51 % which increased to 5.33% during the 10 th Plan period. Due to special developmental initiatives of our Government the State has been able to achieve an annual average growth rate of 6.86% during the 11 th Plan period and is expecting a growth rate of 8.42% (advance estimates) by the end of the 11 th Five Year Plan. If we can maintain the present trend of accelerated growth rate with the help of the multiplier effects of progress already achieved, then we can hope for a projected growth rate of around 9.38% during the 12th Plan period. Agricultural growth rate of the State was negative during the 9 th Plan period. This improved steadily during the 10 th and 11 th Plans. With projected average growth rate of 4.81%, we have been able to achieve the national target of 4% agricultural growth rate during the 11 th Plan. This achievement is all the more remarkable if we take into account the fact that the actual projected national growth rate of agriculture during the 11 th Plan period is 3.06% against the target of 4%. -

The Flood Situation of Assam – a Case Study

The Flood Situation of Assam – A Case Study Mukul Chandra Bora Lecturer (Sélection Grade) in Civil Engineering Dibrugarh Polytechnic, Lahowal: Pin: 786010 Assam, India Abstract The problem caused by water may broadly be catagorised into two major groups’ viz. shortage of water and surplus of water. Shortage of water causes drought and surplus water causes flood. The water is the vital ingredients for the survival of human being but sometimes it may cause woe to the human life not due to insufficient water but due to abundant water which in turn causes the natural disaster called as flood. Assam is situated at the easternmost part of India. Geographically it is at the foothills of the Himalaya. Every year Assam experiences a huge amount of losses due to devastating flood caused by the river Brahmaputra. The losses are more in few places like (Majuli, the biggest river Island), Dhemaji, North Lakhimpur, Dhakuakhana and few places of Barak valley in Assam. The problem of flood is very old in Assam and the solution is very much difficult due to complex and devastating nature of the River Brahmaputra. Both short term and long term measures are sometimes failed to mitigate the losses caused by flood. This paper presents the case study on the losses in terms of livestock, human lives and that in terms of property that have taken place in Dhakuakhana area of Assam. Keywords: Water problem, flood, River, Brahmaputra, losses. 1. Introduction: India is a vast country with lot of diversity in water related problem with woes due to shortage and abundance in water. -

Nature of Hazard: Floods in Assam Map of Affected District

SITUATION REPORT ASSAM FLOODS NATURE OF HAZARD: FLOODS IN ASSAM Following heavy to very heavy rainfall in north -eastern states of India since end- June, the rising flood waters of the Brahmaputra river caused a breach in an embankment in Assam’s Lakhimpur District, Dhakunakhata Gaon Panchayat on 1 July 2009. The 100 metre wide breach on the 5 km long embankment was caused due to the water levels rising to a breach height of 93.03 metres. On 2 July, media reports indicated that the situation has worsened with the release of water from the Kurishu dam in Bhutan at the pace of 698 cubic metres per second. Water has also been released from K arbi Langpi Hydel Project in Assam. The Indian Meteorological Department has predicted isolated extremely heavy falls ( = 25cm) over Assam & Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh during the next 3-4 days. On 3 July, the Central Water Commission reported that the Subansiri river in North Lakhimpur district was flowing above the warning level in a steady rising trend. Following the breach, the District Admi nistration sounded a Red Alert in the affected areas. Official reports on 2 July mention almost 1 lakh people affected in the Dhakuakhana sub-division. The flood protection measures of the Brahmaputra River have totally broken down. The situation has been described as grim and deteriorating. MAP OF AFFECTED DISTRICT (Source: Official website of Lakhimpur district http://lakhimpur.nic.in/ ) 1 Sit Rep - Assam Floods–03 July 2009 DAMAGE DETAILS As of 2 July 2009, the official damage details from the Dhakuakhana sub-division are: Population affected – 95,500 No. -

Bohag Bihu and Other Spring Festivals Among the People of Lakhimpur District of Assam: an Understanding of Their Present Status

Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University ISSN: 1007-1172 Bohag Bihu and other Spring Festivals among the People of Lakhimpur District of Assam: An Understanding of their Present Status ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Submitted by Dr. Montu Chetia Department of History, Kampur College, Nagaon, Assam-782426 Gmail ID: [email protected] Phone: 9101093556 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Volume 16, Issue 11, November - 2020 https://shjtdxxb-e.cn/ Page No: 319 Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University ISSN: 1007-1172 Bohag Bihu and other Spring Festivals among the People of Lakhimpur District of Assam : An Understanding of their Present Status. Dr Montu Chetia ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Bihu is a national festival of Assam celebrated by all sections of the society irrespective of caste, creed and religion. The Bihu is the identity of Assamese people in all over the country. It is also the symbol of unity among the people of the state. There are three kinds of Bihu generally observed in Assam- Bohag Bihu or Rongali Bihu, Magh Bihu or Bhogali Bihu and Kati Bihu or Kongali Bihu. Every Bihu has its own features and characteristics which have enriched the cultural prosperity of Assam as well as the whole north eastern region . On the other hand although Bihu is the national festival of Assam yet it varies in form from place to place which have developed the cultural diversity of the state . Being a part of the state people of Lakhimpur district observe all these Bihus in their customary and ritualistic manner. Along with the Bihus some other spring festivals are also observed in Lakhimpur district with great enthusiasm. The present paper has an attempt to study the nature of these festivals of Lakhimpur district which are primarily observed in the spring season. -

Role of Policy and Institutions in Local Adaptation to Climate Change

Role of Policy and Institutions in Local Adaptation to Climate Change Case studies on responses to too much and too little water in the Hindu Kush Himalayas About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalisation and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. Role of Policy and Institutions in Local Adaptation to Climate Change Case studies on responses to too much and too little water in the Hindu Kush Himalayas Editors Neera Shrestha Pradhan (ICIMOD) Vijay R. Khadgi (ICIMOD) Lisa Schipper (SEI) Nanki -

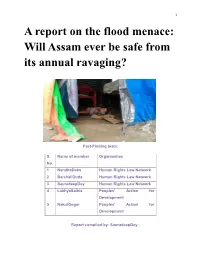

A Report on the Flood Menace: Will Assam Ever Be Safe from Its Annual Ravaging?

1 A report on the flood menace: Will Assam ever be safe from its annual ravaging? Fact-Finding team: S. Name of member Organisation No. 1 NanditaDeka Human Rights Law Network 2 BaishaliDutta Human Rights Law Network 3 SauradeepDey Human Rights Law Network 4 LakhyaSaikia Peoples’ Action for Development 5 NakulGogoi Peoples’ Action for Development Report compiled by: SauradeepDey 2 Contents: S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 List of Abbreviations 3 2 Introduction 5 3 Lakhimpur and its Geopgraphy 7 4 Floods in Lakhimpur 8 5 The Dam effect 10 6 Fact-finding on the effect of floods on the people 14 7 Fact-finding methodology 14 8 The effect of floods in Telahi Block, Lakhimpur 14 9 Effect of Floods in Lakhimpur Block 24 10 A different perspective to floods 27 11 Meeting with the District Project Officer, District 29 Disaster Management Authority, Lakhimpur 12 Interaction with NGOs 31 13 The total effect of the floods of 2017 32 14 Conclusion 34 15 Gallery 40 3 List of Abbreviations: AASU: All Assam Students Union ASDMA: Assam State Disaster Management Authority ASHA: Accredited Social Health Activist CMD: Chairman & Managing Director DC: Deputy Commissioner DDMA: District Disaster Management Authority DPO: District Project Officer DPR: Detailed Project Report EIA: Environment Impact Assessment FLEWS: Flood Early Warning System HRLN: Human Rights Law Network IIT: Indian Institute of Technology MoU: Memorandum of Understanding MW: Mega-watt NEEPCO: North East Electric Power Corporation Limited NESAC: North Eastern Space Application System NGO: Non-Government Organisation NH: National Highway NHPC: National Hydel Power Corporation PAD: Peoples‟ Action for Development 4 PHC: Primary Health Centre P&RD: Panchayat& Rural Development RoR: Run-of-the-river Rs.: Rupees USD: United States Dollar 5 INTRODUCTION Floods are an annual recurrent event in Assam, causing damage worth crores and affecting thousands of lives. -

Assam Power Distribution Company Ltd (Apdcl) Bijulee Bhawan,Paltanbazar, Guwahati-781 001 Cin: U40109as2003sgc007242

ASSAM POWER DISTRIBUTION COMPANY LTD (APDCL) BIJULEE BHAWAN,PALTANBAZAR, GUWAHATI-781 001 CIN: U40109AS2003SGC007242 BID DOCUMENT No APDCL/CGM(PP&D)/RAPDRP/RT-DAS/2019/02 Supply, Installation, Testing & Commissioning of Hardware & Software for implementing “Real Time Data Acquisition System (RT-DAS)” covering 33/11kv Substations of 92 (87+5) RAPDRP & IPDS Non- SCADA towns in Assam Assam Power Distribution Company Limited, 6th Floor, Bijulee Bhawan, Paltanbazar, Guwahati Assam 781001 INDIA e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] NOTICE INVITING TENDER NIT No. APDCL/CGM(PP&D)/RAPDRP/RT-DAS/2019/02/501 Date: 29-07-2019 The Chief General Manager (PP&D), APDCL on behalf of Assam Power Distribution Company Ltd hereby invites responses from experienced and financially sound firm(s) for “Supply, Installation, Testing & Commissioning of Hardware & Software for implementing ‘Real Time Data Acquisition System (RT-DAS)’ covering 33/11kv Substations of 92 (87+5) RAPDRP & IPDS Non-SCADA towns in Assam” . The bid document(s) including changes if any in the Bid Schedule, corrigendum etc. shall be notified on the APDCL website. www.apdcl.org or www.assamtenders.gov.in or both NIT EMD Estimated SCOPE OF WORK No. (in Rs) Cost Supply, Installation, Testing & Commissioning of Hardware & Software for implementing “Real Time Data Acquisition System (RT- DAS)” covering 33/11kv Substations of 92 (87+5) RAPDRP & IPDS Non-SCADA towns in Assam ₹ 10 Lakhs ₹10 Lakhs ₹ 475 lakhs ₹ 475 lakhs DAS/2019/02 DAS/2019/02 APDCL/CGM(PP&D)/RAPDRP/RT- Mode of Tender: E-Tendering (Online) Part I, Techno Commercial Bid and Part-II Price Bid) through the website assamtenders.gov.in Sl Description Date Time No.