Role of Policy and Institutions in Local Adaptation to Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED for the POST of GD. IV of AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT of DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR

LIST OF ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF GD. IV OF AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR Date of form Sl Post Registration No Candidate Name Father's Name Present Address Mobile No Date of Birth Submission 1 Grade IV 101321 RATUL BORAH NAREN BORAH VILL:-BORPATHAR NO-1,NARAYANPUR,GOSAIBARI,LAKHIMPUR,Assam,787033 6000682491 30-09-1978 18-11-2020 2 Grade IV 101739 YASHMINA HUSSAIN MUZIBUL HUSSAIN WARD NO-14, TOWN BANTOW,NORTH LAKHIMPUR,KHELMATI,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 6002014868 08-07-1997 01-12-2020 3 Grade IV 102050 RAHUL LAMA BIKASH LAMA 191,VILL NO 2 DOLABARI,KALIABHOMORA,SONITPUR,ASSAM,784001 9678122171 01-10-1999 26-11-2020 4 Grade IV 102187 NIRUPAM NATH NIDHU BHUSAN NATH 98,MONTALI,MAHISHASAN,KARIMGANJ,ASSAM,788781 9854532604 03-01-2000 29-11-2020 5 Grade IV 102253 LAKHYA JYOTI HAZARIKA JATIN HAZARIKA NH-15,BRAHMAJAN,BRAHMAJAN,BISWANATH,ASSAM,784172 8638045134 26-10-1991 06-12-2020 6 Grade IV 102458 NABAJIT SAIKIA LATE CENIRAM SAIKIA PANIGAON,PANIGAON,PANIGAON,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787052 9127451770 31-12-1994 07-12-2020 7 Grade IV 102516 BABY MISSONG TANKESWAR MISSONG KAITONG,KAITONG ,KAITONG,DHEMAJI,ASSAM,787058 6001247428 04-10-2001 05-12-2020 8 Grade IV 103091 MADHYA MONI SAIKIA BOLURAM SAIKIA Near Gosaipukhuri Namghor,Gosaipukhuri,Adi alengi,Lakhimpur,Assam,787054 8011440485 01-01-1987 07-12-2020 9 Grade IV 103220 JAHAN IDRISH AHMED MUKSHED ALI HAZARIKA K B ROAD,KHUTAKATIA,JAPISAJIA,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 7002409259 01-01-1988 01-12-2020 10 Grade IV 103270 NIHARIKA KALITA ARABINDA KALITA 006,GUWAHATI,KAHILIPARA,KAMRUP -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Chitral Audit Year 2016

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT CHITRAL AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................. ii Preface ................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... v SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... viii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ................................................................................................. viii Table 2: Audit observations Classified by Categories (Rs in million) ...................................... viii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ........................................................................................................ ix Table 4: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................................. x Table 5: Cost Benefit Ratio ......................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 District Government Chitral ......................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

An Indian Englishman

AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN MEMOIRS OF JACK GIBSON IN INDIA 1937–1969 Edited by Brij Sharma Copyright © 2008 Jack Gibson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. ISBN: 978-1-4357-3461-6 Book available at http://www.lulu.com/content/2872821 CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 To The Doon School 5 Bandarpunch-Gangotri-Badrinath 17 Gulmarg to the Kumbh Mela 39 Kulu and Lahul 49 Kathiawar and the South 65 War in Europe 81 Swat-Chitral-Gilgit 93 Wartime in India 101 Joining the R.I.N.V.R. 113 Afloat and Ashore 121 Kitchener College 133 Back to the Doon School 143 Nineteen-Fortyseven 153 Trekking 163 From School to Services Academy 175 Early Days at Clement Town 187 My Last Year at the J.S.W. 205 Back Again to the Doon School 223 Attempt on ‘Black Peak’ 239 vi An Indian Englishman To Mayo College 251 A Headmaster’s Year 265 Growth of Mayo College 273 The Baspa Valley 289 A Half-Century 299 A Crowded Programme 309 Chini 325 East and West 339 The Year of the Dragon 357 I Buy a Farm-House 367 Uncertainties 377 My Last Year at Mayo College 385 Appendix 409 PREFACE ohn Travers Mends (Jack) Gibson was born on March 3, 1908 and J died on October 23, 1994. -

1 Impact of Aga Khan Rural Support Program's Gender Strategy On

Impact of Aga Khan Rural Support Program’s Gender Strategy on Rural Women in District Chitral Rabia Gul Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad Email: [email protected] Abstract The study was conducted in Chitral Valley in the North of Pakistan to explore the gender related activities introduced by the Aga Khan Rural Support Program (AKRSP).The findings show that the AKRSP has been playing a key role in the development of women in the area and initiated development programs in water supply, health and credit facilities. It imparted trainings for the local women in different disciplines through the Women Organizations (WO’s) established in the area. These trainings were recorded and mostly repeated via video cassettes in different villages. Posters and charts were also used to make the trainings easier for the local women to understand. The AKRSP has also been successful to take few hours daily from the Local Government Radio in the area and communicate to the women in their local language about certain issues such as personal hygiene, procedure to get and pay back loans from the micro finance bank of AKRSP, about agricultural practices etc. Practical adoption of these trainings has made positive effect in the lives of the local women in terms of improved agricultural products and increase in income of the respondents. Further, the AKRSP is looking into the possibility of establishing a Community Radio which if established will play a major role for the development of the area. Thus, it is concluded that the AKRSP has made invaluable contributions in improving the access of women to education, health resources and economic empowerment opportunities. -

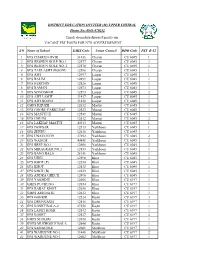

S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1

DISTRICT EDUCATION OFFICER (M) UPPER CHITRAL Phone No: 0943-470252 Email: [email protected] VACANT PST POSTS FOR NTS ADVERTISEMENT S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1 GPS CHARUN OVIR 31436 Charun CU 6045 1 2 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO.1 12577 Charun CU 6045 1 3 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO..2 12578 Charun CU 6045 1 4 GPS TAKLASHT (BOONI) 12596 Charun CU 6045 1 5 GPS AWI 12497 Laspur CU 6045 1 6 GPS BALIM 12499 Laspur CU 6045 1 7 GPS HERCHIN 12526 Laspur CU 6045 1 8 GPS RAMAN 12573 Laspur CU 6045 1 9 GPS SONOGHUR 12593 Laspur CU 6045 2 10 GPS AWI LASHT 31437 Laspur CU 6045 1 11 GPS AWI BOONI 31438 Laspur CU 6045 1 12 GMPS KHUZH 12632 Mastuj CU 6045 1 13 GPS GHORU PARKUSAP 12523 Mastuj CU 6045 1 14 GPS MASTUJ II 12549 Mastuj CU 6045 1 15 GPS CHUINJ 12512 Mastuj CU 6045 2 16 GPS LAKHAP MASTUJ 40313 Mastuj CU 6045 1 17 GPS DEWSAR 12513 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 18 GPS ZHUPU 12610 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 19 GPS UNAVOUCH 37292 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 20 GPS WASUM 40841 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 21 GPS BREP NO.1 12508 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 22 GPS MIRAGRAM NO.2 12553 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 23 GPS BANG BALA 28141 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 24 GPS UJNU 12598 Khot CU 6045 1 25 GPS KHOT (P) 12534 Khot CU 6045 1 26 GPS KHOT 12532 Khot CU 6045 1 27 GPS KHOT (B) 12533 Khot CU 6045 1 28 GPS ANDRA GHECH 12496 Khot CU 6045 1 29 GPS YAKHDIZ 12606 Khot CU 6197 1 30 GMPS PUCHUNG 12654 Khot CU 6197 1 31 GPS RABAT KHOT 12656 Khot CU 6197 1 32 GMPS AMUNATE 12612 Khot CU 6197 1 33 GPS GOHKIR 12524 Kosht CU 6197 3 34 GPS DRUNGAGH 12516 Kosht CU 6197 1 35 GPS KOSHT BALA-2 27550 Kosht -

The Flood Situation of Assam – a Case Study

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264878734 The Flood Situation of Assam – A Case Study Article CITATION READS 1 34,158 2 authors, including: Mukul Bora Dibrugarh University 10 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Mukul Bora on 31 October 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Flood Situation of Assam – A Case Study Mukul Chandra Bora Lecturer (Sélection Grade) in Civil Engineering Dibrugarh Polytechnic, Lahowal: Pin: 786010 Assam, India Abstract The problem caused by water may broadly be catagorised into two major groups’ viz. shortage of water and surplus of water. Shortage of water causes drought and surplus water causes flood. The water is the vital ingredients for the survival of human being but sometimes it may cause woe to the human life not due to insufficient water but due to abundant water which in turn causes the natural disaster called as flood. Assam is situated at the easternmost part of India. Geographically it is at the foothills of the Himalaya. Every year Assam experiences a huge amount of losses due to devastating flood caused by the river Brahmaputra. The losses are more in few places like (Majuli, the biggest river Island), Dhemaji, North Lakhimpur, Dhakuakhana and few places of Barak valley in Assam. The problem of flood is very old in Assam and the solution is very much difficult due to complex and devastating nature of the River Brahmaputra. Both short term and long term measures are sometimes failed to mitigate the losses caused by flood. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

Survey of Predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera

Survey of Predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the Chitral District, Pakistan Author(s): Inamullah Khan, Sadrud Din, Said Khan Khalil and Muhammad Ather Rafi Source: Journal of Insect Science, 7(7):1-6. 2007. Published By: Entomological Society of America DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1673/031.007.0701 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1673/031.007.0701 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Insect Science | www.insectscience.org ISSN: 1536-2442 Survey of predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the Chitral District, Pakistan Inamullah Khan, Sadrud Din, Said Khan Khalil and Muhammad Ather Rafi1 Department of Plant Protection, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan 1 National Agricultural Research Council, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract An extensive survey of predatory Coccinellid beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) was conducted in the Chitral District, Pakistan, over a period of 7 months (April through October, 2001). -

Chitral Case Study April 26.Inddsec2:24 Sec2:24 4/27/2007 1:38:17 PM C H I T R a L

Chapter 3 Observing and Experiencing Flash Floods ocal knowledge on disaster preparedness in the Chitral the mountains. […] The fl ood blocked the river for 10 minutes District of Pakistan includes aspects related to people’s and it became a big lake and destroyed a water mill. The fl ood Lobservation and experience of fl ash fl oods, anticipation of continued until 9 pm. Some big stones are still stuck inside the fl oods, adjustment strategies, and communication strategies. valley.” (Narrated by Islamuddin, Aziz Urahman, Gul Muhammad Jan, Rashidullah, Khan Zarin and Ghulam Jafar, Gurin village, The people of Chitral have knowledge about the history and Gurin Gole, Shishi Koh valley, Lower Chitral) nature of fl ash fl oods in their own locality based on daily observation of their local surroundings, close ties to their “We were ready to take our goats up to the higher pastures environment for survival, and an accumulated understanding when eight days of discontinuous heavy rain fell from June 30th of their environment through generations. They have learned till July 9th 1978. We shifted our animals and family members to interpret their landscape and the physical indicators of past during that period to a nearby village. On July 7th, the river fl ash fl oods. They can also describe and explain how their own started to build up in the main course and to spill over. Some vulnerability to fl oods has changed over time. houses were destroyed. On July 9th even more houses were destroyed. The main fl ow came during the night of July 9th”. -

Seasonal Variation of Drinking Water Quality with Respect to Fluoride and Nitrate in Dhakuakhana Sub-Division of Lakhimpur Distr

Int. J. Chem. Sci.: 7(3), 2009, 1821-1830 SEASONAL VARIATION OF DRINKING WATER QUALITY WITH RESPECT TO FLUORIDE AND NITRATE IN DHAKUAKHANA SUB-DIVISION OF LAKHIMPUR DISTRICT OF ASSAM JAYANTA CHUTIA ∗∗∗ and SIBA PRASAD SARMA a Department of Chemistry, Brahmaputra Valley Academy, Khelmati, NORTH LAKHIMPUR - 787 031 (Assam) INDIA aDepartment of Chemistry, Lakhimpur Girls’ College, NORTH LAKHIMPUR - 787 031 (Assam) INDIA ABSTRACT The present investigation has been undertaken to determine the seasonal variation of the quality of drinking water of the study area Thirty water samples were analysed during May-June 2008 for pH , total hardness, fluoride and nitrate contents by adopting standard methods (APHA-AWWA-WPCF , 1995) and another thirty water samples were analysed during Nov-Dec. 2008 for the same contents. The data obtained were within the standard, permissible limits of WHO. The variations of the pH values were not vary large but an increase was noticeable during winter and a lowering during the post monsoon period. All the water samples were found either soft or moderately hard. The total hardness values were comparatively higher in the water samples collected during the dry season. Fluoride and nitrate contents were found slightly higher during post-monsoon period. Key words : pH, Hardness, Fluoride, Nitrate INTRODUCTION The environment for any living organism has never been constant or static . Comprising over 71% earth’s surface, water is unquestionably the most precious natural resource that exists on our planet 1. Although water is very abundant on this earth, yet it is very precious. Out of the total water reserves of the world, about 97% is salty water (Marine) and only 3% is freshwater. -

Dice Snakes in the Western Himalayas: Discussion of Potential Expansion Routes of Natrix Tessellata After Its Rediscovery in Pakistan

SALAMANDRA 49(4) 229–233 30 December 2013CorrespondenceISSN 0036–3375 Correspondence Dice Snakes in the western Himalayas: discussion of potential expansion routes of Natrix tessellata after its rediscovery in Pakistan Konrad Mebert 1 & Rafaqat Masroor 2 1) Section of Conservation Biology, Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Basel, St. Johanns-Vorstadt 10, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland 2) Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Garden Avenue, Shakarparian, 44000-Islamabad, Pakistan Corresponding author: Konrad Mebert, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 3 September 2012 The dice snake (Natrix tessellata) has a large distribution stan Museum of Natural History and other experts in dif- range, extending from central (Germany) and southern Eu- ferent parts of northern Pakistan failed to find this species rope (Italy, Balkans) in the west, south to Egypt, and east as (e.g., Baig 2001, Khan 2002, Masroor 2012). far as northwestern China and Afghanistan (Mebert 2011a During recent herpetological surveys of wetlands con- and refs. therein). From Pakistan, N. tessellata has been doc- ducted in the framework of the Pakistan Wetlands Pro- umented only once (Wall 1911) with three specimens from gramme (PWP) by WWF-Pakistan, a single female an altitude of ca. 6,000 feet a.s.l. (~ 1,830 m) near Mastuj, of N. tessellata was collected at 1,845 m a.s.l. from the Tehsil of District Chitral, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. Gahkuch Wetlands of Ghizer District, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pa- The only female, collected between 14 and 22 July 1910, laid kistan, on 20 August 2011. The dice snake was preserved as two eggs and subsequently died. -

DETAILS of Npos, SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (Final Copy)

DETAILS OF NPOs, SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (Final copy) (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) (xi) (xii) (xiii) (xiv) (xv) (xvi) (xvii) Name, Address & Contact No. Registration No. Sectors/ Target Size Latest Key Functionaries Persons in Effective Name & Value of Associate Bank Donor Means Mode Cross- Recruitme Detail of of NPO with Registering Function Area and Audited Control Moveable & d Entities Account Base of of Fund border nt Criminal Authority s Communit Accounts Immovable (if any) Details Paymen Payme Activiti Capabilitie /Administrati y available Assets (Bank, t nt es s ve Action (Yes /No) Branch & against NPO Account No.) (if any) 1 AAGHOSH WELFARE DSW/NWFP/254 Educatio Peshawar Mediu Yes Education Naseer Ahmad 01 Lack No;. Nil No. NA N.A N.A 07 Nil ORGANIZATION , ISLAMIA 9 n and m 03009399085 PUBLIC SCHOOL 09-03-2006 General aaghosh_2549@yahoo. BHATYAN CHARSADA Welfare com.com ROAD PESHAWAR 2 ABASEEN FOUNDATION DSW/NWFP/169 Educatio Peshawar mediu 2018 Education Dr. Mukhtiar Zaman 80 lac Nil --------- Both Bank Chequ Nil 20 Nil PAK, 3rd Floor, 272 Deans 9 n & m Tel: 0092 91 5603064 e Trade Centre, Peshawar 09.09.2000 health [email protected] Cantonment, Peshawar, . KPK, Pakistan. 3 Ahbab Welfare Organization, DSW/KPK/3490 Health Peshwar Small 2018 Dr. Habib Ullah 06 lac Nil ---------- Self Cash Cash Nil 08 Nil Sikandarpura G.t Rd 16.03.2011 educatio 0334-9099199 help Cheque Chequ n e 4 AIMS PAKISTAN DSW/NWFP/228 Patient’s KPK Mediu 2018 Patient’s Dr. Zia ul hasan 50 Lacs Nil 1721001193 Local Throug Bank Nil Nil 6-A B-3 OPP:Edhi home 9 Diabetic m Diabetic Welfare 0332 5892728, 690001 h Phase #05 Hayatabad 24,03.04 Welfare /Awareness 091-5892728 MIB Cheque Peshawar.