Please Scroll Down for Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Permittee Name: City of Daly City

FY 2017-2018 Annual Report Permittee Name: City of Daly City Table of Contents Section Page Section 1 – Permittee Information ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 Section 2 – Provision C.2 Municipal Operations ......................................................................................................... 2-1 Section 3 – Provision C.3 New Development and Redevelopment ....................................................................... 3-1 Section 4 – Provision C.4 Industrial and Commercial Site Controls ......................................................................... 4-1 Section 5 – Provision C.5 Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination ..................................................................... 5-1 Section 6 – Provision C.6 Construction Site Controls .................................................................................................. 6-1 Section 7 – Provision C.7 Public Information and Outreach .................................................................................... 7-1 Section 9 – Provision C.9 Pesticides Toxicity Controls ................................................................................................ 9-1 Section 10 – Provision C.10 Trash Load Reduction ................................................................................................... 10-1 Section 11 – Provision C.11 Mercury Controls .......................................................................................................... -

Menu! with in New Orleans

HOW DO YOU WANT YOUR STEAK? FEATURED DESSERT Weekly Specials Steak Lovers Uptown Entrees Semper Fi SouthsideCafe.net SOUTHSIDE HOMEMADE BREAD PUDDING All made with our tender, shredded ribeye steak! SOUTHERN FRIED STEAK 3154 Pontchartrain Dr. / Slidell, LA 70458 This classic New Orleans dessert is a Southside favorite! We STEAK NIGHT! Certified Angus Beef® Steak, breaded, golden fried and served serve it up with our rich & decadent Whiskey sauce. 4.99 BONFOUCA FRENCH DIP with your choice of country white or roast beef gravy. 13.99 ALL ENTREES SERVED WITH 2 SIDES 1/2 lb. of shredded ribeye & pepper jack cheese on toasted French Dine-In Only • COLESLAW • SWEET POTATO FRIES add 99¢ bread, with warm au jus for dipping . 12.99 Call For Carry-Out SOUTHSIDE SIRLOIN • MASHED POTATOES • STEAMED VEGGIES add 1.99 ® Our 8oz. center-cut Certified Angus Beef Sirloin is aged 21 days • POTATO SALAD • FRENCH ONION SOUP add 1.99 BLACK & BLEU POBOY for maximum tenderness and flavor. 23.99 1/2 lb. of shredded ribeye steak with bleu cheese & raw red onion • HOUSE SALAD • SOUP OF THE DAY 985-643-6133 Bonfouca French Dip on toasted French bread. 13.99 • FRENCH FRIES • 4 BEAN & TURKEY SOUP VEAL PARMESAN • HUSH PUPPIES (4) • CUP OF GUMBO Our paneed veal, topped with zesty marinara sauce and melted OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK! • MAC & CHEESE • Chicken & Sausage RIBEYE PHILLY Provolone cheese over buttered toast. 15.99 1/2 lb. of shredded ribeye, sauteed Add roast beef debris; chili; or • Seafood add 1.99 Monday - Saturday | 11am - 10pm “Peaux” Boys onion, pepper, mushrooms & OPEN FACE ROAST BEEF bacon & sour cream 99¢ ea. -

The Training and Development of Principals in the Management of the Curriculum

THE TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT OF PRINCIPALS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF THE CURRICULUM by ARUNACHELLAN DAYANUNDAN PADAYACHEE THESIS submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR EDUCATIONIS in EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT in the FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND NURSING at the RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY PROMOTER : PROF BR GROBLER CO-PROMOTER : PROF TC BISSCHOFF FEBRUARY 1999 II THE TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT OF PRINCIPALS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF THE CURRICULUM A D PADAYACHEE THE TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT OF PRINCIPALS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF THE CURRICULUM A D PADAYACHEE PROMOTER: PROFESSOR B R GROBLER CO-PROMOTER: PROFESSOR T C BISSCHOFF ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere, and heartfelt thanks and gratitude to: The Creator for his Divine intervention and for granting me the strength, courage and perseverance to complete this project.. My promoter of this thesis, Professor B R Grobler. My sincere appreciation and gratitude for his constructive criticism, encouragement, valuable support, insights and assistance and guidance throughout this study. My co-promoter, Professor T C Bisschoff for his constant encouragement and positive support and guidance throughout this research. Cyril Samuels, Roy Reddy and Raj Mestry for their commitment, hardwork, dedication, assistance, support and team work throughout our studies. My parents Mr and Mrs K A Padayachee for the fountain of inspiration which they provided in directing and leading me through life. My wife Umsha and my children Avashni, Trishanta and Dasevan for their patience, understanding and encouragement throughout my studies. My In-Laws, Mr and Mrs Pillay for their support and blessing during my studies. Rand Afrikaans University for their support and Mr JA Vermeulen, deputy rector for his assistance, encouragement and support. -

Mobile Video Production "Flypack" SPECIFICATIONS

SPECIFICATIONS Mobile Video Production "Flypack" CONFIDENTIAL DESIGN INFORMATION - Unauthorized use, reproduction or dissemination of this document is strictly prohibited. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. VIDEO DESIGN AND SUPPORT A. HD Recorder B. HD Rack Monitoring C. Utility Monitor D. Program and Multiview Monitors E. HD Switching and Routing a. Video Control 2 ME Surface b. Video Switcher 2 ME c. Redundant Power Supply for Switcher d. Rack Mount System for Switcher and Control Surface e. Aux 16x1 Control Panels F. HD Scan convergence 2. CAMERAS A. HD PTZ Video Cameras B. HD PTZ Video Controller 3. TRIPODS A. Camera Support B. Heads and Arms C. Tripod Legs and Accessories 4. AUDIO DESIGN AND SUPPORT A. Audio and Mixer Processing B. Production Speakers & Processing C. Audio Embedder D. Audio Distribution E. Intercom Systems a. Wired Specs b. Wireless Specs c. UHF 2-Audio Channel Wireless Synthesized Base Station d. UHF 2-Audio Channel Wireless Synthesized Transceiver 2 CONFIDENTIAL DESIGN INFORMATION - Unauthorized use, reproduction or dissemination of this document is strictly prohibited. 5. CUSTOM REMOTE CASE SYSTEM A. Fly Pack Case B. Fly Pack Accessory Case C. Tripod Cases D. Utility Support E. Other Rackmount Items 6. CABLE MANAGEMENT A. Specialty Cables 7. POWER MANAGEMENT A. Power Distro B. UPS Backup 8. ENGINEERING A. Networking B. IO Panels C. Sub IO Panel D. Intercom Diagram E. Video Diagram F. Audio Diagram G. Switcher Dimensions H. Flypack Model I. Assembly 3 CONFIDENTIAL DESIGN INFORMATION - Unauthorized use, reproduction or dissemination of this document is strictly prohibited. 1. VIDEO DESIGN AND SUPPORT A. HD Recorder Blackmagic HyperDeck Studio Pro Quantity: 4 SSD recorder is a broadcast HD based solid state deck that includes 3G-SDI and HDMI connections so you can work in all SD and HD formats up to 1080p30. -

Liste Des Films FEMIS 2021 Par Départements Et Par Ordre Chronologique

LISTE DES FILMS RECOMMANDÉS PAR LA FÉMIS 2021 Lors des rentrée 2017 puis 2020, il fut demandé aux Directeurs-Directrices des Départements et aux instances responsables de la Fémis de constituer une liste des 30 films considérés comme les plus indispensables : pour les élèves de leur secteur de spécialité (selon les DD) ou pour l’histoire du cinéma et des arts filmiques en général (selon les responsables administratifs et techniques). Il ne s’agit donc pas d’une liste des films favoris, mais des titres estimés parmi les plus nécessaires pour nourrir l’imaginaire formel des élèves, pour aider ceux-ci à approfondir leur connaissance de l’histoire d’une discipline, pour servir de repères communs dans le cadre d’un enseignement. Voici les résultats de la campagne 2020-2021. Ils ont vocation à évoluer chaque année en fonction des nouvelles rencontres de chacun-e avec le cinéma. Cette liste collective s’ajoute à celle des « 208 films » constituée par Alain Bergala, fondée sur le principe de la découverte de sa propre esthétique par un auteur. Ensemble, ces listes établissent une proposition pour quiconque – élèves de La Fémis, candidat-e-s, cinéphiles de tous horizons – voudrait commencer son initiation aux histoires du cinéma et des arts filmiques. I. LISTES DES DÉPARTEMENTS ET SECTEURS II. SYNTHÈSE PAR ORDRE CHRONOLOGIQUE *** 1 I. LISTES DES DÉPARTEMENTS ET SECTEURS [PAR ORDRE ALPHABÉTIQUE] - ANALYSE ET CULTURE CINÉMATOGRAPHIQUE (NICOLE BRENEZ) - DÉCOR (LAURENT OTT, ANNE SEIBEL) - DIRECTION (NATHALIE COSTE-CERDAN) - DIRECTION DES ÉTUDES (FRÉDÉRIC -

Management's Discussion and Analysis Altice

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS ALTICE INTERNATIONAL S.à r.l. FOR THE THREE MONTHS ENDED MARCH 31, 2020 Contents Chapter page 1 Overview 2 2 Strategy and performance 8 3 Basis of presentation 9 4 Group financial review 10 5 Revenue 14 6 Adjusted EBITDA 17 7 Operating profit of the Group 18 8 Result of the Group - items below operating expenses 19 9 Liquidity and capital resources 21 10 Capital Expenditures 23 11 Key operating measures 24 12 Other disclosures 25 13 Key Statement of Income items 26 1 1 OVERVIEW 1.1 Group Business 1.1.1 Overview of the Group’s business The Group is a multinational group operating across two sectors: (i) telecom (broadband and mobile communications) and (ii) content and media. The Group operates in Portugal, Israel and the Dominican Republic. The Group also has a global presence through its online advertising business Teads. The parent company of the Group is Altice International S.à r.l. (the “Company”). The Group had expanded internationally in previous years through several acquisitions of telecommunications businesses, including: MEO in Portugal; HOT in Israel; and Altice in the Dominican Republic. The Group’s acquisition strategy has allowed it to target cable, FTTH or mobile operators with what it believes to be high-quality networks in markets the Group finds attractive from an economic, competitive and regulatory perspective. Furthermore, the Group is focused on growing the businesses that it acquired organically, by focusing on cost optimization, increasing economies of scale and operational synergies and improving quality of its network and services. -

LA FICTION Di SKY CINEMA: Uno Sguardo a New York Rimanendo in Italia

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Economia e Gestione delle Arti e delle Attività Culturali Tesi di Laurea LA FICTION di SKY CINEMA: uno sguardo a New York rimanendo in Italia Relatore Dott. Alessandro Tedeschi Turco Correlatore Prof.ssa Valentina Carla Re Laureanda Alessandra Bernardi Matricola 812482 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 INDICE INTRODUZIONE ................................................................................................................................. 2 CAPITOLO I DALLA PALEOTELEVISIONE ALLA NEOTELEVISIONE .................................. 4 1.1 La prima rivoluzione televisiva .............................................................................................. 7 1.2 Fininvest e il duopolio .............................................................................................................. 21 CAPITOLO II DALLA NEOTELEVISIONE AL NEO-SAT ......................................................... 32 2.1 La Neotelevisione ....................................................................................................................... 32 2.2 La regolamentazione del sistema ......................................................................................... 40 2.3 Nuovi formati televisivi............................................................................................................ 53 2.4 La televisione a pagamento in Italia.................................................................................... 59 CAPITOLO III SKY: LA RIVOLUZIONE SATELLITARE -

Quality-TV- Und Online-Serien

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2011 Quality TV: Eine kurze Einführung in die Geschichte und Ästhetik neuer amerikanischer Fernsehserien Blanchet, Robert Abstract: Serien wie Six Feet Under, Lost, The Wire oder Dexter sind das Ergebnis eines markanten Wandels, der sich in den letzten Jahren in der amerikanischen Fernsehlandschaft vollzogen hat und dur- chaus mit filmhistorischen Umbrüchen wie der Nouvelle Vague verglichen werden kann. Auch hier führten gesellschaftliche, technologische und wirtschaftliche Veränderungen zu einer außergewöhnlich innovativen Schaffensperiode, in der eine neue Generation von Filmemachern die Normen der Unterhaltungsindus- trie herausforderte und nachhaltig veränderte. Der vorliegende Sammelband nimmt den bislang wenig erforschten Trend zum Anlass, um sich Phänomenen des Seriellen aus film-, medien- und kulturwis- senschaftlicher Perspektive zu nähern. Neben den sogenannten Qualitätsserien aus den USA werden Fallbeispiele aus anderen Ländern und Kulturkreisen wie Lateinamerika beleuchtet. Historisch reicht das Spektrum von den Anfängen des Films bis hin zu den Remakes und Sequels des zeitgenössischen Blockbusterkinos. Mit einem Beitrag über Online-Serien ist neben Film und Fernsehen auch das Internet vertreten. Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-52468 Book Section Originally published at: Blanchet, Robert (2011). Quality TV: Eine kurze Einführung in die Geschichte und Ästhetik neuer amerikanischer Fernsehserien. In: Blanchet, Robert; Köhler, Kristina; Smid, Tereza; Zutavern, Julia. Serielle Formen: Von den frühen Film-Serials zu aktuellen Quality-TV- und Online-Serien. Marburg: Schüren, 37-70. 36 Zur Einführung Pearson, Roberta (2007) «LOST in Transition: From Post-Network to Post-Televi- Robert Blanchet sion». -

Chapter 14 the Idea of Love in the TV Serial Drama in Treatment

1 Chapter 14 The Idea of Love in the TV Serial Drama In Treatment Christine Lang I felt from the beginning that mental problems can be very universal, which is why we deal with archetypical problems. —Hagai Levi, creator of BeTipul1 As the history of film and film theory has repeatedly shown, the relationship between cinema and psychoanalysis is a fruitful one. However, the Israeli TV serial drama BeTipul (2005–2008)2 and its American adaptation In Treatment (2008–2010) are the first TV series to be entirely restricted to the conversation between therapist and patient.3 This chapter will discuss how the narrative of In Treatment focuses on the patient–doctor relationship as a forbidden trope and on how the therapist, Dr. Paul Weston (played by Gabriel Byrne), is caught up in conflicts as a result of his incipient transference love. He feels something for his patient, but he knows that he shouldn’t. This “dark” love story constitutes the linchpin and principal subject of the first season of In Treatment. At first this essay gives a definition of a TV serial drama as an auteur film; then it outlines the story lines of In Treatment. The essay examines In Treatment from a specific perspective, with an eye to its structure and its filmic and aesthetic means and with special attention to its dramaturgy and the communicative constellation of its narrative. The last two sections of the essay address the subject of transference love and how it is represented in In Treatment. 1 2 Auteur Series Like the Israeli original series BeTipul, the first season of In Treatment, which is the primary focus of this essay, was broadcast five times a week, with a single episode each day from Monday through Friday. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide

OPFOR WORLDWIDE EQUIPMENT GUIDE TRADOC DCSINT Threat Support Directorate DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Worldwide Equipment Guide Introduction This Worldwide Equipment Guide (WEG) serves as an interim guide for use in training, simulations, and modeling until the publication of FM 100-65, Capabilities-Based Opposing Force: Worldwide Equipment Guide. The WEG is designed for use with the FM 100-60 series of capabilities-based opposing force field manuals. It provides the basic characteristics of selected equipment and weapons systems readily available to the capabilities-based OPFOR, and generally listed in either FM 100-61, Armor- and Mechanized-Based Opposing Force: Organization Guide or FM 100-63, Infantry-Based Opposing Force: Organization Guide. Selected weapons systems and equipment are included in the categories of infantry weapons, infantry vehicles, reconnais- sance vehicles, tanks/assault vehicles, antitank, artillery, air defense, engineer and logistic systems, and rotary-wing aircraft. The pages in this WEG are designed for insertion into loose-leaf notebooks. Since this guide does not include all possible OPFOR systems identified in the OPFOR field manuals, equipment sheets covering additional systems not contained in this initial issue will be published periodically. Systems selected will be keyed directly to the baseline equipment contained in the 100-60 series and substitute systems found in the appropriate substitution matrix. The WEG is scheduled for eventual publication on the worldwide web for use by authorized government or- ganizations. WORLDWIDE OPFOR EQUIPMENT Due to the proliferation of weapons through sales and resale, wartime capture, and li- censed or unlicensed production of major end items, distinctions between equipment as friendly or OPFOR have blurred. -

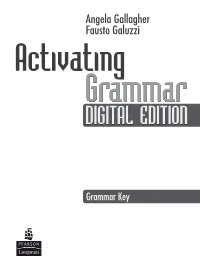

Activating Grammar Key.Pdf

Angela Gallagher Fausto Galuzzi ActivatingActivating Grammar DIGITAL EDITION Grammar Key GrammarkEy EssEntial elEmEnts 1 Pluralofnouns 2 1 ’re 2 ’s 3 ’s 4 Is 5 ’s 6 ’s 7 are 8 are 9 ’m 1 televisions boys cities knives lives tomatoes potatoes 3 1 Is he from Warsaw? Yes, he is. 2 Is his videos watches sandwiches classes English good? No, it isn’t. 3 Are his parents kisses foxes photos universities in England? No, they aren’t. 4 Is Polish food toys schools offices roofs nice? Yes, it is. 5 Is it cold in Poland? It’s cold in winter. 6 Are you happy? Yes, I am. 2 Sostantivi con plurale irregolare: women people teeth feet children 4 1 aren’t 2 ’re 3 ’s 4 ’s 5 ’s 6 aren’t 7 isn’t 8 aren’t 9 isn’t 3 1 b) - potatoes - patate 2 a) - radios - radio 3 b) - shelves - scaffali 4 a) - secretaries - segretarie 5 b) - beaches - spiagge 4 Qualifyingadjectives 6 b) - plays - commedie 7 b) - brushes - spazzole 8 a) - cliffs - scogliere 1 1 revolutionary design 2 small 9 a) - pencils - matite car 3 spacious vehicle 4 leather seats 5 powerful engine 6 mega stereo system 4 sunglasses shoes two T-shirts two dresses two scarves my photos my keys two 2 1 Is the train late? 2 I am not tired! 3 It brushes isn’t a new project. 4 Are you happy? 5 Sue is angry. 6 You are a nice intelligent 5 1 buzzes 2 zoos 3 roofs 4 faxes 5 flies boy. -

Financial Documentation

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS ALTICE LUXEMBOURG S.A. FOR THE SIX MONTH PERIOD ENDED JUNE 30, 2019 Contents 1 OVERVIEW 2 2 STRATEGY AND PERFORMANCE 10 3 KEY FACTORS AFFECTING THE GROUP's RESULTS OF OPERATIONS 12 4 BASIS OF PRESENTATION 14 5 GROUP FINANCIAL REVIEW 15 6 REVENUE 19 7 ADJUSTED EBITDA 22 8 OPERATING PROFIT OF THE GROUP 24 9 RESULT OF THE GROUP - ITEMS BELOW OPERATING EXPENSES 26 10 LIQUIDITY AND CAPITAL RESOURCES 28 11 CAPITAL EXPENDITURES 30 12 KEY OPERATING MEAUSURES 32 13 OTHER DISCLOSURES 33 14 KEY INCOME STATEMENT ITEMS 37 1 The Group is a multinational group operating across three sectors: (i) telecom (broadband and mobile communications), (ii) content and media and (iii) advertising. The Group operates in Western Europe (comprising France and Portugal), Israel, the Dominican Republic and the French overseas territories (comprising Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, La Réunion and Mayotte (the “French Overseas Territories”)). The parent company of the Group is Altice Luxembourg S.A. (the “Company”). The Group had expanded internationally in previous years through several acquisitions of telecommunications businesses, including: SFR and MEO in Western Europe; HOT in Israel; and Altice Hispaniola and Tricom in the Dominican Republic. The Group’s acquisition strategy has allowed it to target cable, FTTH or mobile operators with what it believes to be high-quality networks in markets the Group finds attractive from an economic, competitive and regulatory perspective. Furthermore, the Group is focused on growing the businesses that it acquired organically, by focusing on cost optimization, increasing economies of scale and operational synergies and improving quality of its network and services.