Alan Close Thesis (PDF 512Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before Colonisation

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1-1-2015 A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation Mike Donaldson University of Wollongong, [email protected] Les Bursill University of Wollongong Mary Jacobs TAFE NSW Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Donaldson, Mike; Bursill, Les; and Jacobs, Mary: A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation 2015. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/581 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation Abstract Twenty thousand years ago when the planet was starting to emerge from its most recent ice age and volcanoes were active in Victoria, the Australian continent’s giant animals were disappearing. They included a wombat (Diprotodon) seen on the right, the size of a small car and weighing up to almost three tons, which was preyed upon by a marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) on following page. This treedweller averaging 100 kilograms, was slim compared to the venomous goanna (Megalania) which at 300 kilograms, and 4.5 metres long, was the largest terrestrial lizard known, terrifying but dwarfed by a carnivorous kangaroo (Propleopus oscillans) which could grow three metres high. Keywords before, aboriginal, colonisation, 1:, history, volume, illawarra Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details Bursill, L., Donaldson, M. -

Report Structure

Front cover images Top left: Burrawangs at Riversdale – an important traditional food source for Indigenous people. Photo: S Feary Top right: Axe grinding grooves at Eearie Park. Photo: J Walliss Bottom left: Pulpit Rock, an important cultural site for local Indigenous people. Photo: Bundanon Trust website Bottom right: Working on country. Graham Smith, Nowra LALC Sites Officer surveying for Indigenous sites at Riversdale. Photo: H Moorcroft ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ii Indigenous Cultural Heritage Management Plan for the Bundanon Trust Properties 2011 – 2015 Warning This document contains images, names and references to deceased Indigenous people. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Indigenous Cultural Heritage Management Plan for the Bundanon Trust Properties 2011 – 2015 i Acknowledgements Developing this plan has relied on the support and input of staff of the Bundanon Trust and in this regard we extend out thanks to Henry Goodall, Gary Storey, Jennifer Thompson, Jim Birkett, Mary Preece and Regina Heilman for useful discussions. We particularly appreciate the guidance and support of Deborah Ely in her management of the project. Jim Walliss generously shared his extensive historical knowledge of the area and informed us of the location of two archaeological sites. Special thanks go to the Bega Valley Historical Society for giving us access to their research on the Biddulph diaries and to Peter Freeman and Roger Hobbs for background on the Bundanon Trust Properties Heritage Management Plan. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service provided a boat for a survey of the riparian zone and thanks go to Rangers Noel Webster and Bruce Gray for their assistance. We thank the Board of the Nowra Local Aboriginal Land Council for extending their support for the project and especially to Graham Smith for his skills and experience in archaeological field survey. -

Conrad Martens WORKS in OIL Catalogue of Works

Conrad Martens WORKS IN OIL Catalogue of Works Compiled by Michael Organ Thirty Victoria Street 1989 1 Contents Introduction Conrad Martens & Oil Painting Guide to the Catalogue 1 Field Descriptions 2 Codes Index to Catalogue Catalogue of Works Appendices 1 Attribution of Conrad Martens Portraits 2 Cave Paintings 3 Southern Tableland Views 4 References to Oil Paintings (1837‐1979) Bibliography 2 Introduction This catalogue aims to identify all works executed in oil (and associated media such as body colour and gauche) by Conrad Martens during his career as an artist, and validate them with those noted in his manuscript ‘Account of Pictures painted at Sydney, N.S.Wales [1835‐78]’ (Dixson Library MS142 & MS143), or any of his other records such as letters, diaries, and notes on painting. Also included are portraits in oil of Martens by artists such as Maurice Felton and Mr Nuyts. Martens’ ‘Account of Pictures’ provides an invaluable source for identifying his more than 100 extant works in oil. Though ‘Account of Pictures’ specifically identifies only 35 oil paintings, many others noted ‐ but not identified ‐ therein as oils, can be matched with known works. ‘Account of Pictures’ identifies the following 35 oil paintings: Title Date Bota Fogo, Rio Janiero 20 March 1838 Brush at Illawarra 26 May 1838 Oropena, Tahiti 31 May 1838 Salcombe Castle 2 May 1839 Govets Leap 23 May 1839 View of New Government House 28 Oct. 1841 Sydney from St Leonards 14 Nov. 1841 View from Rose Bay 30 Nov. 1841 View of Old Government House 21 Jany. 1842 Government Stables 31 Jany. -

Volume 33 Issue 4 Spring 2008

Volume 33 Issue 4 Camp above Bluff Tarn, Kosciusko National Park Spring 2008 Rolling Grounds above Whites River Hut, Kosciusko National Park Photo: Bruce McKinney Contributions of interesting, especially typical and spectacular bushwalking photos are sought. you don’t want the same photographers all the time, do you? What’s for Dinner? Riley’s Paddock, west of Finchley Trig, Photo: David Morrison Yengo National Park Walk Safely—Walk with a Club T h e Bushwalker The Official Publication of the Confederation of Bushwalking Clubs NSW Volume 33, Issue 4, Spring 2008 From the editor’s desk. ISSN 0313 2684 Editor: Roger Caffin ell, we have several articles on safety this time. There’s one [email protected] from Keith Maxwell of the BWRS about the need to let Graphic Design & Assembly: Wpeople know where you are when you need rescuing. It can Barry Hanlon be a bit hard to find you otherwise. There’s another, rather shocking in a way, from Michael Keats of The Bush Club, about live ammunition Confederation Officers: and chemical warfare shells from WW II hidden near Lithgow. He is President: Wilf Hilder hoping that a bit of publicity might persuade the Defence Dept to clean Administration Officer: up its act. Finally, there’s one from the Editor on ‘When Things Go [email protected] Wrong’, which shows just how powerful nature can be in the Website: www.bushwalking.org.au mountains, and emphasising that there is a time for any of us when retreat is the smart and only option. We don’t want dead heroes. -

A History of Aboriginal Illawarra, Volume 2 : Colonisation Mike Donaldson University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2017 A History of Aboriginal Illawarra, Volume 2 : Colonisation Mike Donaldson University of Wollongong, [email protected] Les Bursill University of Wollongong, [email protected] Mary Jacobs TAFE NSW, [email protected] Publication Details Mike Donaldson, Les Bursill and Mary Jacobs, A History of Aboriginal Illawarra, Volume 2: Colonisation, Dharawal Publications, Yowie Bay, 2017, 130p. Volume 1 is HERE. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A History of Aboriginal Illawarra, Volume 2 : Colonisation Abstract Near Broulee Point, south of Batemans Bay, once stood a wooden look-out platform used for generations by Leonard Nye’s family. The Dhurga were fisherfolk and through the ages they would gather to assess the seas and the weather before setting off. The oj b of the lookout who remained there was to signal those on the water and on the beach below about the location and direction of sea mammals and shoals of fish. Such lookout posts exist also at Hill 60 at Port Kembla and up and down the South Coast, and it is from them that people observed the passage of James Cook’s ship in 1770. One of them told her granddaughter Coomee, who died at Ulladulla in 1914, all about “the first time the white birds came by”. During the vessel’s slow northward movement along the South Coast over eight days, heavy surf at Bulli Beach prevented a provisioning party from getting ashore on 28 April. -

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Northern Rivers Region

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Northern Rivers Region A new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours © Copyright Office of Environment and Heritage on behalf of State of NSW With the exception of photographs, the Office of Environment and Heritage and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs (OEH copyright). The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is part of the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH). Throughout this strategy, references to NPWS should be taken to mean NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Minister for the Environment. For further information contact: Northern Rivers Region Coastal Branch National Parks and Wildlife Service Office of Environment and Heritage Department of Premier and Cabinet PO Box 856 Alstonville NSW 2477 Phone: (02) 6627 0200 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au/pollution. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74293 616 1 OEH 2012/0365 August 2013 This plan may be cited as: OEH 2012, Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17, Northern Rivers Region: a new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. -

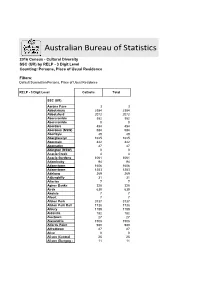

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census - Cultural Diversity SSC (UR) by RELP - 3 Digit Level Counting: Persons, Place of Usual Residence Filters: Default Summation Persons, Place of Usual Residence RELP - 3 Digit Level Catholic Total SSC (UR) Aarons Pass 3 3 Abbotsbury 2384 2384 Abbotsford 2072 2072 Abercrombie 382 382 Abercrombie 0 0 Aberdare 454 454 Aberdeen (NSW) 584 584 Aberfoyle 49 49 Aberglasslyn 1625 1625 Abermain 442 442 Abernethy 47 47 Abington (NSW) 0 0 Acacia Creek 4 4 Acacia Gardens 1061 1061 Adaminaby 94 94 Adamstown 1606 1606 Adamstown 1253 1253 Adelong 269 269 Adjungbilly 31 31 Afterlee 7 7 Agnes Banks 328 328 Airds 630 630 Akolele 7 7 Albert 7 7 Albion Park 3737 3737 Albion Park Rail 1738 1738 Albury 1189 1189 Aldavilla 182 182 Alectown 27 27 Alexandria 1508 1508 Alfords Point 990 990 Alfredtown 27 27 Alice 0 0 Alison (Central 25 25 Alison (Dungog - 11 11 Allambie Heights 1970 1970 Allandale (NSW) 20 20 Allawah 971 971 Alleena 3 3 Allgomera 20 20 Allworth 35 35 Allynbrook 5 5 Alma Park 5 5 Alpine 30 30 Alstonvale 116 116 Alstonville 1177 1177 Alumy Creek 24 24 Amaroo (NSW) 15 15 Ambarvale 2105 2105 Amosfield 7 7 Anabranch North 0 0 Anabranch South 7 7 Anambah 4 4 Ando 17 17 Anembo 18 18 Angledale 30 30 Angledool 20 20 Anglers Reach 17 17 Angourie 42 42 Anna Bay 789 789 Annandale (NSW) 1976 1976 Annangrove 541 541 Appin (NSW) 841 841 Apple Tree Flat 11 11 Appleby 16 16 Appletree Flat 0 0 Apsley (NSW) 14 14 Arable 0 0 Arakoon 87 87 Araluen (NSW) 38 38 Aratula (NSW) 0 0 Arcadia (NSW) 403 403 Arcadia Vale 271 271 Ardglen -

Culture in Translation

Culture in Translation The anthropological legacy of R. H. Mathews Culture in Translation The anthropological legacy of R. H. Mathews Edited by Martin Thomas Translations from the French by Mathilde de Hauteclocque and from the German by Christine Winter Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 15 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Mathews, R. H. (Robert Hamilton), 1841-1918. Culture in translation : the anthropological legacy of R. H. Mathews. Bibliography. ISBN 9781921313240 (pbk.) ISBN 9781921313257 (online) 1. Mathews, R. H. (Robert Hamilton), 1841-1918. 2. Aboriginal Australians - Social life and customs. 3. Aboriginal Australians - Languages. 4. Ethnology - Australia. I. Thomas, Martin Edward. II. Title. (Series : Aboriginal history monograph ; no.15). 305.800994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters-Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editor Kitty Eggerking Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Region Localities Inclusion Support Agency New South Wales

u Inclusion and Professional Support Program (IPSP) Grant Application Process 2013-2016 Region Localities Inclusion Support Agency New South Wales This document lists the localities which comprise each Statistical Area Level 2 within each ISA Region in New South Wales. Description This document provides greater detail on the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Areal Level 2 boundaries within each ISA Region. The localities listed in this document are the ‘gazetted locality boundaries’ supplied by the state or territory government and may differ from commonly used locality and/or suburb names. This document does not provide a definitive list of every suburb included within each ISA Region as this information is not available. Postcodes are provided for those localities which either: cross ISA boundaries or where the same locality name appears in more than one ISA region within the same state or territory. IPSP 2013-2016: ISA Region Localities – New South Wales ISA Region 1 – Sydney Inner – Localities Alexandria Eastlakes Point Piper Annandale Edgecliff Port Botany Balmain Elizabeth Bay Potts Point Balmain East Enmore Pyrmont Banksmeadow (Postcode: 2042) Queens Park Barangaroo Erskineville Randwick Beaconsfield Eveleigh Redfern Bellevue Hill Forest Lodge Rose Bay Birchgrove Glebe Rosebery Bondi Haymarket Rozelle Bondi Beach Hillsdale Rushcutters Bay Bondi Junction Kensington South Coogee Botany Kingsford St Peters Bronte La Perouse Stanmore Camperdown Leichhardt Surry Hills Centennial -

Gerringong to Bomaderry Princes Highway Upgrade

Gerringong to Bomaderry Princes Highway upgrade ROUTE OPTIONS DEVELOPMENT APPENDIX I - PRELIMINARY INDIGENOUS AND NON-INDIGENOUS HERITAGE ASSESSMENT NOVEMBER 2007 ISBN 9781921242038 RTA/Pub. 07.349I Gerringong to Bomaderry Princes Highway Upgrade Preliminary Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Assessment The Roads and Traffic Authority NSW November 2007 Document No.: Navin Officer heritage consultants Pty Ltd Gerringong to Bomaderry Princes Highway Upgrade Prepared for The Roads and Traffic Authority NSW Prepared by Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd Level 11, 44 Market Street, Sydney NSW 2000, PO Box Q410, QVB Post Office NSW 1230, Australia T +61 2 8295 3600 F +61 2 9262 5060 www.maunsell.com ABN 20 093 846 925 In association with Navin Officer Heritage Consultants Pty Ltd Unit 4, 71 Leichhardt St, Kingston, ACT 2604 21 November 2007 DEV06/04-HE-NO-Heritage-Rev-2 © Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd 2007 The information contained in this document produced by Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd is solely for the use of the Client identified on the cover sheet for the purpose for which it has been prepared and Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd undertakes no duty to or accepts any responsibility to any third party who may rely upon this document. All rights reserved. No section or element of this document may be removed from this document, reproduced, electronically stored or transmitted in any form without the written permission of Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd. 60021933 - Gerringong to Bomaderry Princes Highway Upgrade Preliminary Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Assessment – November -

Coolabah, No.11, 2013, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre D’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat De Barcelona

Coolabah, No.11, 2013, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona A Koori’s Perspective of Place: Connections to the NSW Upper South Coast 1 Terrence Wright Copyright©2013 Terrence Wright. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Introduction I am an Educator. I am also an Aboriginal designer and carver. These two beings though are complimentary. My work is inspired by the practice of carving – a practice long undertaken by Aboriginal peoples right around the country known as Australia. Carvings can include tree carving or ‘dendroglyphs’ and ‘petroglyphs’ or rock carvings or rock engravings. My specific influence is the tree carvers as my father and his father both worked in the bush. My work is in timber didjeridus and glass objects, including glass didjeridus! I work under the banner of Yabundja Designs. I see what I do in my art as an extension of my work in education. Aboriginal people no matter who you are or where you are constantly educate and re-educate people about Aboriginal Australia. My carvings tell stories and through those stories transpire the educative process. There are a variety of explanations as to why the tree carvings took place within Aboriginal communities. For example, the Gamilaroi people in the central northwest designed their tree carvings around powerful symbols used for boys being ushered into manhood at elaborate ceremonies called bora. When a host clan was intending to hold a bora, a messenger would be sent far afield to invite neighbouring clans to attend. -

Visitor Guide NSW National Parks 2011 North Coast

Lush rainforests, dî p blue seas, beaches 6\GQH\ golden sand - e Nor Coast entices wi its rich natural nders North Coast The North Coast region abounds with natural treasures, centred on the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage Area and sparkling beaches. Also within our north coast parks are waterfalls, mountains, towering dunes, rocky headlands, coastal lakes and estuaries. Waiting for you to explore are the magnifi cent icons – Cape Byron lighthouse, Wollumbin Mount Warning, the Dorrigo Rainforest Centre with its accessible walkway, Trial Bay Gaol, Sea Acres Rainforest Centre at Port Macquarie, Sugarloaf Point lighthouse at Seal Rocks and Myall Lakes National Park. Rocky headlands and plenty of white sandy beaches A serene moment on the beach at are some features of Tomaree National Park Arakoon State Conservation Area Photography: LEFT: DECCW, RIGHT: M. Van Ewijk / DECCW 14 For more information visit www.nswnationalparks.com.au/northcoast HIGHLIGHTS DORRIGO RAINFOREST CENTRE SEA ACRES DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK RAINFOREST CENTRE PACIFIC DRIVE PORT MACQUARIE The Dorrigo Rainforest Centre and Skywalk are only an hour’s drive west Sea Acres offers tours of the rare of Coffs Harbour. An interactive display subtropical rainforest, an ecology display, guides visitors of all ages through different a gift shop and conference facilities. There aspects of this World Heritage listed is an entry fee to the elevated rainforest rainforest, and staff can provide detailed walkway. Open 7 days. The Rainforest information on national parks throughout Café offers a pleasant leafy venue for north-east NSW. The Rainforest Shop relaxed dining. is open 7 days, and sells specialised books and guides, posters, prints, craft Phone 6582 3355 and souvenirs, and you can enjoy lunch Café enquiries 6582 4444 or coffee at the award-winning Canopy Café.