Report Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

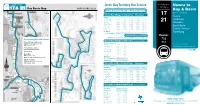

Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for Bus Nowra to Numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty

LOOK FOR BUS Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for bus Nowra to numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty. Ltd Transport initiative supplied by the Commonwealth of Australia and serviced by Nowra Coaches Bay & Basin Nowra Coaches Pty Ltd - Phone 4423 5244 Buses Servicing Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – (Weekdays) 17 Departs Nowra Wreck Bay Village 6.25am 9.10am 11.10am 12.45pm 2.17pm Huskisson Summercloud Bay 6.30am 9.15am 11.15am 12.48pm 2.22pm 21 Green Patch 6.40am 9.25am 11.25am 12.58pm 2.32pm Vincentia Jervis Bay Village 6.47am 9.32am 11.32am 1.05pm 2.39pm HMAS Creswell 6.50am 9.35am 11.35am 1.08pm 2.42pm Bay & Basin Visitors Centre 6.55am 9.42am 11.41am 1.13pm 2.48pm Vincentia 7.08am 9.53am 11.51am 1.23pm 2.58pm Central Avenue Bus Departs Tomerong To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 7.10am 9.55am – 1.25pm** 3.00pm **Services Sanctuary Point, St. Georges Basin & Basin View only. Routes (Via Bay & Basin) – – 11.53am – 3.30pm Connecting Bus Operators 732 Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – Saturday & Sunday Kennedy’s Bus and Coach Departs (Via Bay & Basin) 733 www.kennedystours.com.au See back cover for Tel: 1300 133 477 Wreck Bay Village 9.08am 1.20pm Summercloud Bay 9.13am 1.25pm detailed route descriptions Premier Motor Service Green Patch 9.23am 1.35pm www.premierms.com.au Jervis Bay Village 9.30am 1.42pm Price 50c Tel: 13 34 10 HMAS Creswell 9.33am 1.45pm Visitors Centre 9.38am 1.48pm Shoal Bus Tel: 02 4423 2122 Vincentia 9.48am 1.58pm Email: [email protected] Bus Departs To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 9.50am – Stuarts Coaches (Via -

Booderee National Park Management Plan 2015-2025

(THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK – INSIDE FRONT COVER) Booderee National Park MANAGEMENT PLAN 2015- 2025 Management Plan 2015-2025 3 © Director of National Parks 2015 ISBN: 978-0-9807460-8-2 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9807460-4-4 (Online) This plan is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Director of National Parks. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director of National Parks GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 This management plan sets out how it is proposed the park will be managed for the next ten years. A copy of this plan is available online at: environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/parks-australia/publications. Photography: June Andersen, Jon Harris, Michael Nelson Front cover: Ngudjung Mothers by Ms V. E. Brown SNR © Ngudjung is the story for my painting. “It's about Women's Lore; it's about the connection of all things. It's about the seven sister dreaming, that is a story that governs our land and our universal connection to the dreaming. It is also about the connection to the ocean where our dreaming stories that come from the ocean life that feeds us, teaches us about survival, amongst the sea life. It is stories of mammals, whales and dolphins that hold sacred language codes to the universe. It is about our existence from the first sunrise to present day. We are caretakers of our mother, the land. It is in balance with the universe to maintain peace and harmony. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Agenda of Strategy and Assets Committee

Meeting Agenda Strategy and Assets Committee Meeting Date: Tuesday, 18 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Membership (Quorum - 5) Clr John Wells - Chairperson Clr Bob Proudfoot All Councillors Chief Executive Officer or nominee Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies / Leave of Absence 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Strategy and Assets Committee - 13 April 2021 ........................................................ 1 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Mayoral Minute 5. Deputations and Presentations 6. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice SA21.73 Notice of Motion - Creating a Dementia Friendly Shoalhaven ................... 23 SA21.74 Notice of Motion - Reconstruction and Sealing Hames Rd Parma ............. 25 SA21.75 Notice of Motion - Cost of Refurbishment of the Mayoral Office ................ 26 SA21.76 Notice of Motion - Madeira Vine Infestation Transport For NSW Land Berry ......................................................................................................... 27 SA21.77 Notice of Motion - Possible RAAF World War 2 Memorial ......................... 28 7. Reports CEO SA21.78 Application for Community -

Morton State Conservation Area Plan of Management

NSW NATIONAL PARKS & WILDLIFE SERVICE Morton State Conservation Area Plan of Management environment.nsw.gov.au © 2019 State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. DPIE shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by DPIE and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. DPIE asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment 2019. Cover photo: View from Three Peaks Lookout over the upper Grassy Gully valley. -

101 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

101 bus time schedule & line map 101 Bomaderry to Worrigee via Nowra (Loop Service) View In Website Mode The 101 bus line (Bomaderry to Worrigee via Nowra (Loop Service)) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bomaderry: 7:20 AM - 4:10 PM (2) Nowra: 9:20 AM - 5:15 PM (3) South Nowra: 7:50 AM (4) West Nowra: 5:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 101 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 101 bus arriving. Direction: Bomaderry 101 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Bomaderry Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:20 AM - 4:10 PM Bomaderry Station Tuesday 7:20 AM - 4:10 PM Shoalhaven Hospital, Scenic Dr Wednesday 7:20 AM - 4:10 PM Nowra Bus Terminal, Stewart Pl Thursday 7:20 AM - 4:10 PM 1 Stewart Place, Nowra Friday 7:20 AM - 4:10 PM Stockland Nowra Saturday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM St Anns St at Wallace St 134 St Anns Street, Nowra Salisbury Dr at Tarraba St 37 Salisbury Drive, Nowra 101 bus Info Direction: Bomaderry Greenwell Point Rd opp Old Southern Rd Stops: 34 Trip Duration: 68 min Carrington Park Dr at Burradoo Cr Line Summary: Bomaderry Station, Shoalhaven 7 Carrington Park Drive, Nowra Hospital, Scenic Dr, Nowra Bus Terminal, Stewart Pl, Stockland Nowra, St Anns St at Wallace St, Salisbury Sophia Rd at Sullivan St Dr at Tarraba St, Greenwell Point Rd opp Old 41 Sophia Road, Worrigee Southern Rd, Carrington Park Dr at Burradoo Cr, Sophia Rd at Sullivan St, Rayleigh Garden Reserve, Rayleigh Garden Reserve, Rayleigh Dr Rayleigh Dr, Rayleigh Dr at Regelia Pde, Isa Rd at 7 -

Regional Overview

1 Regional Overview Population: 172,650 persons (2016 est. resident population) Growth Rate: 3.74% (2011 – 2016) 0.51% average annual growth Key Industries: Retail, Health Care and Social Assistance, Construction, Manufacturing, Defence, Tourism and Agriculture Number of Businesses by Industry – (top 10 shown) Construction 2484 Agriculture, forestry and fishing 1250 Rental, hiring and real estate services 1165 Retail trade 1101 Professional, scientific and technical services 989 Tourism 863 Financial and insurance services 647 Health care and social assistance 638 Transport, postal and warehousing 631 Other services 613 Total Businesses FSC (2014) 12,123 Council Areas: City of Shoalhaven, Eurobodalla Shire and Bega Valley Shire Location & Environment The Far South Coast (FSC) of NSW is a region covering 14,230sqkm of coastal land from Berry in the north to the NSW/ Victoria border in the south. 2 It is made up of three local government areas – Shoalhaven City, Eurobodalla Shire and Bega Valley Shire. The FSC is strategically located between the nation’s main capital cities, approximately 2-5 hours from Sydney, 6-10 hours from Melbourne and just 2 hours from Canberra. The FSC is renowned for its natural beauty with nearly 400 km of coastline; numerous marine parks, thirty one national park areas and extensive areas of state parks. The region generally has mild, pleasant weather. The summers are warm with an average maximum of 27°C while the winters generally have a minimum range from 1°C to 12°C. (Bureau of Meteorology). People & Community The estimated resident population of the FSC as at 30 June 2016 was 172,500 persons. -

Shoalhaven City Council Notices

p 02 9698 5266 f 02 9699 2433 CLIENT PROOF Leonards Key No: 72292 Section/Sort: Public Notices Account Exec: Heidi Client Rev. No: 1 Publication: South Coast Register Ad Size (HxW): 30cm x 8 columns Operator Name: Insertion Date: Wed 11/10/17 Size (HxW): 30 x 26cm Proofreader Name: Please proof your advertisement thoroughly and advise us of your approval as soon as possible via eziSuite, email or fax. Client Signature: The final responsibility for the accuracy of your advertisement content and placement details rests with you, our valued client. Leonards will not be held responsible for any errors or for liability under the Trade Practices Act. Date/Time: Shoalhaven City Council Notices www.shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au DA17/1760 65 Chapman St, CALLALA BAY DA17/1682 15 McKay St, NOWRA DA17/1757 148 The Wool Rd, ST GEORGES BASIN Public Notices Residential. Alterations and additions. Residential. Alterations and additions. Residential. New second occupancy. DA17/1838 4 Hunter St, CALLALA BAY DA17/1998 36 Killara Rd, NOWRA CD17/1465 36 Loralyn Ave, ST GEORGES BASIN Proposed Road Name off Old Residential. Alterations and additions. Residential. Single new dwelling. Southern Road, South Nowra Residential. Alterations and additions. DA17/1995 5 Morton St, CALLALA BAY CD17/1458 33 Killara Rd, NOWRA DA17/1608 Lot 75 Invermay Ave, TOMERONG Residential. New second occupancy. In accordance with Section 162 of the Roads Act Residential. Single new dwelling. Residential. Single new dwelling. 1993 and Part 2 of the Roads Regulation 2008, CD17/1439 3 Sir Henry Cr, CALLALA BEACH CD17/1470 16 Jindalee Cr, NOWRA DA17/1244 2 Duncan St, VINCENTIA Council wishes to advise that the following road Residential. -

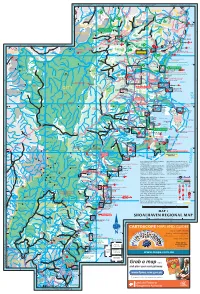

Shaolhaven Region

For adjoining map see Cartoscope's For adjoining map see Cartoscope's TO ALBION B Capital Country Tourist Map TO MOSS VALE 10km TO ROBERTSON 6km C Illawarra Region Tourist Map D PARK 5km TO SHELLHARBOUR 5km MOSS RD RD 150º30'E 150º20'E 150º40'E 150º50'E O Fitzroy Creek O RD R E Bundanoon Falls KIAMA B TD 15 Carrington Reservoir M AM Creek 79 in J Minnamurra Falls nam Dam urr Minnamurra a VALE Belmore River RIVER Falls Y Falls A 31km Creek Jamberoo MERYLA TD 8 BUDDEROO 9 W MERYLA Fitzroy MYRA H G Falls y I r n H o r o SF 907 a n Gerringong TD 9 34º40'S a g TRACK d n Falls n RD e u r NATIONAL B r Upper TO MARULAN Kiama River a Kangaroo B Valley BARRENCOUNCIL WINGECARRIBEE VALE Barrengarry PARK GROUNDS Saddleback TOURIST DRIVE Mt 7 8 Hampden Bridge: Mt 14 Built 1898, Saddleback 1 RD NR Lookout 1 oldest suspension BUDDEROO Foxground Mt Carrialoo bridge in Australia COUNCIL Mt CK Moollatoo Kangaroo Valley Creek Mt Pleasant Power Station Lookout Bendeela B Pondage For detail see ro WOODHILL ge Wattamolla RD Bendeela Map 10 rs MTN Werri Beach Bendeela Campground RD 3 LA Proposed RD OL RODWAY PRINCES Power TAM Upgrade Station Kangaroo WAT NR RD KAN 18 Gerringong Valley GA DR 13 RO BLACK For adjoining map see Cartoscope's 15 O ASH TD 7 A TO MARULAN 8km Capital Country Tourist Map Broughton NR 11 MT DEVILS CAOURA VALLEY GLEN NR RD Village Mt Skanzi 79 DAM Gerroa RD 9 For detail Berry Ck Marulan TALLOWA CAMBERWARRA RAILWAY 150º00'E 150º10'E Mt Phillips RANGE NR TD 7/8 see Map 15 Quarry FIRE Tallowa Dam Steep and very windy road, BEACH RD Black Head -

Annual Report 2014–2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2014–2015 With ongoing funding from the Australian Government, Bundanon Trust supports arts practice and engagement with the arts through its residency, education, exhibition and performance programs. In preserving the natural and cultural heritage of its site Bundanon promotes the value of the landscape in all our lives. ISSN 1323-4358 BUNDANON TRUST PO Box 3343 North Nowra NSW 2541 T 61 2 4422 2100 F 61 2 4422 7190 bundanon.com.au CONTACT Deborah Ely — Chief Executive Officer [email protected] Design: Boccalatte Print: Oxygen PHOTOS Cover and this page: Performance, Dance Integrated Australia, 2014. Image: Julie Ryan Black Nectar, Keith Armstrong and Laurence English, Siteworks, 2014 Image: Heidrun Löhr CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 5 2014–2015 REVIEWED 6 RESIDENCIES 8 PUBLIC PROGRAMS 12 EDUCATION AND OUTREACH 20 COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITIONS 24 BUILT AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT 26 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 28 MANAGEMENT AND ACCOUNTABILITY 30 FINANCIAL REPORT 2014–2015 32 Bundanon Trust Annual Report 2014–2015 3 Francesco Celata, Roger Benedict and Umberto Clerici, Sydney Soloist concert, Riversdale, 2015 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE e have had the Bundanon Local Committee, chaired by Fred Neville, includes opportunity once again Shoalhaven representatives Robbie Collins, Mark Graham, W this year to share our Roslyn Poole, and Gerry Moore and has provided dedicated unique collection with tens guidance for our arts and education initiatives in the region. of thousands of Australians The Living Landscape environmental initiative has been through our touring exhibition guided by a Steering Committee of experts led by John Kerin, Arthur Boyd: An Active Witness. along with representatives from partners Landcare Australia, Over the last three years the Local Land Services and Greening Australia. -

Margaret Goldrick Remembers Arthur Boyd

Vol. 9 No. 6 JulyI August 1999 $5.95 Tim Bonyhady on john McDonald and the state of Australian art criticism john Sendy on China 50 years after the Revolution Margaret Goldrick remembers Arthur Boyd Bill Garner on the great and disappearing art of camping Peter Mares reports on the Indonesian election Special Book Offer VOONG WHY WEREN'T WE TOLD? A personal search for the truth about our history by Henry Reynolds Why Weren't We Told~ is historian Henry Reynolds' account of his own journey to understanding the truth about our history. Drawing on personal experiences and historical observations, Reynolds looks at Australia's history of relations with indigenous people from colonisation to the present day, identifying the myths that were taught in the past and explaining why and how they cam e about. Thanks to Viking Books, Eureka Street has 10 copies of Why Weren't We Told! to give away, each worth $24.95 . Ju st put your name and address on the back of an envelope and send it to: Emel<a Street July/August Book Offer, PO Box 553, Richmond VIC 3121. Executive Director CHARLES STURT Australian Centre for U N V E R S T y Christianity and Culture Australian Centre for (Located at Canberra) Christianity and Culture The Australian Centre is an ecumenica l foundation. endo rsed b y the Natio nal Council of Churches and sponsored hy the Anglican Diocese of Ca nberra and Goulburn and Charles Srun University. The Centre is committed to the celebratio n and nourishment o f the encounter and dialogue between Christianity and all as pects o f modern Australian life. -

A History of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before Colonisation

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1-1-2015 A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation Mike Donaldson University of Wollongong, [email protected] Les Bursill University of Wollongong Mary Jacobs TAFE NSW Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Donaldson, Mike; Bursill, Les; and Jacobs, Mary: A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation 2015. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/581 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation Abstract Twenty thousand years ago when the planet was starting to emerge from its most recent ice age and volcanoes were active in Victoria, the Australian continent’s giant animals were disappearing. They included a wombat (Diprotodon) seen on the right, the size of a small car and weighing up to almost three tons, which was preyed upon by a marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) on following page. This treedweller averaging 100 kilograms, was slim compared to the venomous goanna (Megalania) which at 300 kilograms, and 4.5 metres long, was the largest terrestrial lizard known, terrifying but dwarfed by a carnivorous kangaroo (Propleopus oscillans) which could grow three metres high. Keywords before, aboriginal, colonisation, 1:, history, volume, illawarra Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details Bursill, L., Donaldson, M.