Introduction MARY LINDEMANN and JARED POLEY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stamps of the German Empire

UC-NRLF 6165 3fi Sfifi G3P6 COo GIFT OF Lewis Bealer THE STAMPS OF THE GERMAN STATES By Bertram W. H. Poole PART I "Stamps of the German Empire" BADEN MECKLENBURG-SCHWERIN BAVARIA MECKLENBURG-STREUTZ BERGEDORF OLDENBURG BREMEN PRUSSIA BRUNSWICK SAXONY HAMBURG SCHLESWIG-HOISTEIN HANOVER LUBECK WURTEMBERG HANDBOOK NUMBER 6 Price 35c PUBLISHED BY MEKEEL-SEVERN-WYLIE CO. BOSTON, MASS. i" THE STAMPS OF THE GERMAN EMPIRE BY BERTRAM W. H. POOLE AUTHOR OF The Stamps of the Cook Islands, Stamp Collector's Guide, Bermuda, Bulgaria, Hong Kong, Sierra Leone, Etc. MEKEEL-SEVERN-WYLIE CO. HANDBOOK No. 6 PUBLISHED BY MEKEEL-SEVERN-WYLIE CO. BOSTON, MASS. GIFT OF FOREWORD. In beginning this series of articles little is required in the way of an intro- ductory note for the title is lucid enough. I may, however, point out that these articles are written solely for the guidance of the general collector, in which category, of course, all our boy readers are included. While all im- portant philatelic facts will be recorded but little attention will be paid to minor varieties. Special stress will be laid on a study of the various designs and all necessary explanations will be given so that the lists of varieties appearing in the catalogues will be plain to the most inexperienced collector. In the "refer- ence list," which will conclude each f chapter, only > s.ucji s. arfif>s; Hifl >e in- cluded as may; ie,'con&tfJdrekt ;"e,ssntial" and, as such,' coming 'within 'the scope of on the.'phJlaJtetist'lcoUeetijig' ^ene^l" lines. .V. -

Auction V Iewing

AN AUCTION OF Ancient Coins and Artefacts World Coins and Tokens Islamic Coins The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Monday 30 September 2013 10:00 Free Online Bidding Service AUCTION www.dnw.co.uk Monday 23 September to Thursday 26 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Strictly by appointment only Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 27, 28 and 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Monday 30 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale VIEWING Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or [email protected] Catalogued by Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley, Jim Brown, Tim Wilkes and Nigel Mills In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley or Jim Brown Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Session 1, 10.00 Ancient Coins from the Collection of Dr Paul Lewis.................................................................3001-3025 Ancient Coins from other properties ........................................................................................3026-3084 Ancient Coins – Lots ..................................................................................................................3085-3108 Artefacts ......................................................................................................................................3109-3124 10-minute intermission prior to Session 2 World Coins and Tokens from the Collection formed by Allan -

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

Download Complete File

BOOK REVIEWS LudgER KöRntgEn and dOmInIK WaSSEnhOVEn (eds.), Re - ligion and Politics in the Middle Ages: Germany and England by Com - parison / Religion und Politik im Mittelalter: Deutschland und England im Vergleich , Prince albert Studies, 29 (Berlin: Walter de gruyter, 2013), 234 pp. ISBn 978 3 11 026204 9. € 99.95. uS$140.00 this volume brings together the papers given at the annual confer - ence of the Prince albert Society, held at Coburg in 2010. In keeping with the Society’s stated aim to promote research on anglo-german relations, the theme chosen was religion and politics in medieval England and germany. the papers cover a wide span of time, from Carolingian Francia to England and germany in the late middle ages, but are held together by a common interest in the complex inter relationship of religion and politics in these years. they vary greatly in length, with some constituting little more than fully refer - enced versions of the orally delivered paper (nelson, Ormrod, and Fößel), and others representing very substantial studies in their own right (görich and Weiler). after a brief preface detailing the background to the collection, the book begins with an introduction (presumably by the editors, though this is not clearly stated). an overview of the volume’s aims is given, as well as summaries of the individual papers. there is little attempt to saying anything new here and the exercise seems to be designed to help the casual reader pick out which article(s) might be of interest. In any case, the summaries given are fair and judicious, although there are a few egregious slips. -

Coins and Medals;

CATALOGUE OF A VERY IKTERESTIKG COLLECTION'' OF U N I T E D S T A T E S A N D F O R E I G N C O I N S A N D M E D A L S ; L ALSO, A SMx^LL COLLECTION OF ^JMCIEjMT-^(^REEK AND l^OMAN foiJMg; T H E C A B I N E T O F LYMAN WILDER, ESQ., OF HOOSICK FALLS, N. Y., T O B E S O L D A T A U C T I O N B Y MJSSSBS. BAjYGS . CO., AT THEIR NEW SALESROOMS, A/'os. yjg and ^4.1 Broadway, New York, ON Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, May 21, 23 and 2Ji,, 1879, AT HALF PAST TWO O'CLOCK. C a t a l o g u e b y J o l a n W . H a s e l t i n e . PHILADELPHIA: Bavis & Phnnypackeh, Steam Powee Printers, No. 33 S. Tenth St. 1879. j I I I ih 11 lii 111 ill ill 111 111 111 111 11 1 i 1 1 M 1 1 1 t1 1 1 1 1 1 - Ar - i 1 - 1 2 - I J 2 0 - ' a 4 - - a a 3 2 3 B ' 4 - J - 4 - + . i a ! ! ? . s c c n 1 ) 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 'r r '1' '1' ,|l l|l 1 l-Tp- S t ' A L E O P O n e - S i x t e e n t h o f a n I n c h . -

Coins of Zurich Throughout History

Coins of Zurich throughout History Not so long ago it was assumed that Zurich was founded in Roman times, and that the earliest coins of Zurich dated from the 9th century AD. In the meantime we know that Celtic tribes settled in Zurich long before the Romans – and that the first Zurich coins emerged about 1000 years earlier than hitherto believed, namely in the course of the 1st century BC. Hence our tour through the monetary history of Zurich starts in ancient Celtic times. Afterwards, however, no money was minted in Zurich over centuries indeed. Only under Eastern Frankish rule did the small town on the end of the lake become a mint again. And since then the Zurich mint remained in use – with longer and shorter discontuniations until 1848: then the Swiss franc was created as the single currency of Switzerland, and the coins from Zurich as well as all the rest of the circulating Swiss coins were devaluated and replaced. During the 1000 years between the minting of the first medieval coin of Zurich and the last money of the Canton of Zurich in 1848, our money served the most diverse purposes. It was used as means of payment and as article of trade, as measure of value and as savings and, last but not least, for prestige. The coins of Zurich reflect these various functions perspicuously – but see for yourself. 1 von 33 www.sunflower.ch Helvetia, Tigurini, Potin Coin (Zurich Type), Early 1st Century BC Denomination: AE (Potin Coin) Mint Authority: Tribe of the Tigurini Mint: Undefined Year of Issue: -100 Weight (g): 3.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Others Owner: Sunflower Foundation Sometime around the beginning of the 1st century BC, Celts of the Tigurini tribe broke the ground of the Lindenhof in Zurich. -

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined An Analysis ofthe Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies F. A. HAYEK Nohel Laureate 1974 Diseases desperate grown, By desperate appliances are reli'ved, Or not at all. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (Hamlet, Act iv, Scene iii) THIRD EDITION ~~ Published by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1990 First published in October 1976 Second Edition, revised and enlarged, February 1978 Third Edition, with a new Introduction, October 1990 by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 2 Lord North Street, Westminster, London SWIP 3LB © THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1976, 1978, 1990 Hobart Paper (Special) 70 All rights reseroed ISSN 0073-2818 ISBN 0-255 36239-0 Printed in Great Britain by GORON PRO-PRINT CO LTD 6 Marlborough Road, Churchill Industrial Estate, Lancing, W Sussex Text set in 'Monotype' Baskeroille CONTENTS Page PREFACE Arthur Seldon 9 PREFACE TO THE SECOND (EXTENDED) EDITION A.S. 11 AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION 13 A NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION 16 THE AUTHOR 18 INTRODUCTION TO THE THIRD EDITION Geoffrey E. Wood 19 THE PRACTICAL PROPOSAL 23 Free trade in money 23 Proposal more practicable than utopian European currency 23 Free trade in banking 24 Preventing government from concealing depreciation 25 II THE GENERALISATION OF THR UNDERLYING PRINCIPLE 26 Competition in currency not discussed by economists 26 Initial advantages of government monopoly in money 27 III THE ORIGIN OF THE GOVERNMENT PREROGATIVE OF MAKING MONEY 28 Government certificate of metal weight and purity 29 The appearance of paper money 31 -

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars Lecture Set #34 Project of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club Photographed by John Cork & Raymond Reingohl Introduction Trade Dollars in this presentation are grouped into 3 categories • True Trade Dollars • It was intended to circulate in remote areas from its minting source • Accepted Trade Dollars • Trade dollar’s value was highly accepted for trading purposes in distant lands • Examples are the Spanish & Mexican 8 Reales and the Maria Theresa Thaler • Controversial Trade Dollars • A generally accepted dollar but mainly minted to circulate in a nation’s colonies • Examples are the Piastre de Commerce and Neu Guinea 5 Marks This is the Schlick Guldengroschen, commonly known as the Joachimstaler because of the large silver deposits found in Bohemia; now in the Czech Republic. The reverse of the prior two coins. Elizabeth I authorized this Crown This British piece created to be used by the East India Company is nicknamed the “Porticullis Crown” because of the iron grating which protected castles from unauthorized entry. Obverse and Reverse of a Low Countries (Netherlands) silver Patagon, also called an “Albertus Taler.” Crown of the United Amsterdam Company 8 reales issued in 1601 to facilitate trade between the Dutch and the rest of Europe. Crown of the United Company of Zeeland, minted at Middleburg in 1602, similar in size to the 8 reales. This Crown is rare and counterfeits have been discovered to deceive the unwary. The Dutch Leeuwendaalder was minted for nearly a century and began as the common trade coin from a combination of all the Dutch companies which fought each other as well as other European powers. -

False ? Model.Combipageviewmodel

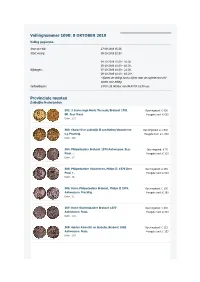

Veilingnummer 1090: 8 OKTOBER 2019 Veiling gegevens Start pre-bid: 27-08-2019 05:26 Start veiling: 08-10-2019 22:50 04-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. 05-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. Kijkdagen: 07-10-2019 10:00 - 21:00. 08-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00*. *tijdens de veiling kunt u kijken naar de objecten tot 100 kavels voor afslag. Ophaaldagen: 14 t/m 18 oktober van 09.00 tot 16.00 uur. Provinciale munten Zuidelijke Nederlanden 502: 2 Souvereign Maria Theresia/Brabant 1761 Openingsbod: € 500 BR. Zeer Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 600 Delm. 215. 503: Chaise D'or Lodewijk II van Malen/Vlaanderen Openingsbod: € 1.500 z.j. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 1.500 Delm. 466. 504: Philipsdaalder Brabant 1574 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 70 Fraai -. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 17. 505: Philipsdaalder Vlaanderen, Philips II. 1575 Zeer Openingsbod: € 150 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 500 Delm. 36. 506: Halve Philipsdaalder Brabant, Philips II 1574, Openingsbod: € 100 Antwerpen. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 180 Delm. 51. 507: Halve Statendaalder Brabant 1577 Openingsbod: € 200 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 200 Delm. 118. 508: Gulden Albrecht en Isabella, Brabant 1602 Openingsbod: € 125 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 155 Delm. 235. 509: Patagon Philips IV, Brabant 1664 Brussel. Zeer Openingsbod: € 90 Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 150 Delm. 285. 510: Halve dukaton Philips IV, Brabant 1638 Openingsbod: € 100 Brussel. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 289. 511: Dukaton Maria Theresia 1754 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 80 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 130 Delm. 375. 512: Halve Dukaton Maria Theresia 1750 Openingsbod: € 50 Antwerpen. Zeer Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 85 Delm. 379. 513: Kronenthaler Franz I 1765 B. -

HARMONY Or HARMONEY

Niklot Kluessendorf Harmony in money – one money for one country ICOMON e-Proceedings (Shanghai, 2010) 4 (2012), pp. 1-5 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org Harmony in money – one money for one country Niklot Klüßendorf Amöneburg, Germany [email protected] This paper discusses the German reforms from 1871 to 1876 for 26 States with different monetary traditions. Particular attention is paid to the strategy of compromise that produced harmony, notwithstanding the different traditions, habits and attitudes to money. Almost everybody found something in the new system that was familiar. The reform included three separate legal elements: coinage, government paper money and banknotes, and was carried out in such a way to avoid upsetting the different parties. Under the common roof of the new monetary unit, traditional and regional elements were preserved, eg in coin denominations, design, and even in the colours of banknotes. The ideas of compromise were helpful to the mental acceptance of the new money. As money and its tradition are rooted in the habits and feelings of the people, the strategy of creating harmony has to be taken into consideration for many monetary reforms. So the German reforms were a good example for the euro that was introduced with a similar spirit for harmony among the participating nations. New currencies need intensive preparation covering political, economic and technical aspects, and even psychological planning. The introduction of the euro was an outstanding example of this. The compromise between national and supranational ideas played an important role during the creation of a single currency for Europe. Euro banknotes, issued by the European Central Bank, demonstrate the supranational idea. -

Chapter 4 the Kadlec Family Prepares To

Kadlec Family History Chapter 4. The Kadlec Family Prepares to Emigrate to the USA Kadlecovi.com Chapter 4. The Kadlec Family Prepares to Emigrate to the USA Generation 6: František Kadlec (B. 12 Aug 1800, M. 28 Jan 1823, D. 14 Aug 1876) Figure 4-1. Only known photo of the man believed to be František Kadlec CHAPTER 4 - 21 - Edition 1.11.24.2011 Kadlec Family History Chapter 4. The Kadlec Family Prepares to Emigrate to the USA Kadlecovi.com As a young man aged twenty-two years, František (1800) bought farmland no. 13 for 400 gulden on 15 Jan 1823, nearly two weeks before the date of his marriage to Anna Hudcová. “It‟s a little known fact…” The Austro-Hungarian gulden The Gulden was the currency of the Austro-Hungarian Empire between 1754 and 1892. The name Gulden was used on Austrian (German-language) banknotes, whilst the name Florin was used on Austrian coins and forint was used on the Hungarian banknotes and coins. With the introduction of the Conventionsthaler in 1754, the Gulden was defined as half a Conventionsthaler, equivalent to 1/20 of a Cologne mark of silver and subdivided into 60 Kreuzer. The Gulden became the standard unit of account in the Hapsburg Empire and remained so until 1892 (Wikipedia). In 1857, the Vereinsthaler was introduced across Germany and Austria-Hungary, One year earlier, Jakub Hudec the father of Anna (wife of František (1800)) bought the farm landwith no. a silver5 for 848 content gulden of 16⅔ on 18 grams. March This 1822. was The slightly transfer less of than title 1.5for timesfarmland the no.silver 5 is noteworthycontent of asthe this Gulden. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521632277 - The Logic of Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond Walter Mattli Excerpt More information 1 Introduction 1 The phenomenon of regional integration Regional integration schemes have multiplied in the past few years and the importance of regional groups in trade, money, and politics is increasing dramatically. Regional integration, however, is no new phenomenon. Examples of StaatenbuÈnde, Bundesstaaten, Eidgenossen- schaften, leagues, commonwealths, unions, associations, pacts, confed- eracies, councils and their like are spread throughout history. Many were established for defensive purposes, and not all of them were based on voluntaryassent. This book looks at a particular set of regional integration schemes. The analysis covers cases that involve the voluntary linking in the economic and political domains of two or more formerly independent states to the extent that authorityover keyareas of national policyis shifted towards the supranational level. The ®rst major voluntaryregional integration initiatives appeared in the nineteenth century. In 1828, for example, Prussia established a customs union with Hesse-Darmstadt. This was followed successively bythe Bavaria WuÈrttemberg Customs Union, the Middle German Commercial Union, the German Zollverein, the North German Tax Union, the German MonetaryUnion, and ®nallythe German Reich. This wave of integration spilled over into what was to become Switzer- land when an integrated Swiss market and political union were created in 1848. It also brought economic and political union to Italyin the risorgimento movement. Integration fever again struck Europe in the last decade of the nineteenth century, when numerous and now long- forgotten projects for European integration were concocted. In France, Count Paul de Leusse advocated the establishment of a customs union in agriculture between Germanyand France, with a common tariff bureau in Frankfurt.1 Other countries considered for membership were Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Spain.