1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia

— Early draft. Please do not quote, cite, or redistribute without written permission of the authors. — How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia After 1815∗ Thilo R. Huningy and Nikolaus Wolfz Abstract We analyze the formation oft he German Zollverein as an example how geography can shape institutional change. We show how the redrawing of the European map at the Congress of Vienna—notably Prussia’s control over the Rhineland and Westphalia—affected the incentives for policymakers to cooperate. The new borders were not endogenous. They were at odds with the strategy of Prussia, but followed from Britain’s intervention at Vienna regarding the Polish-Saxon question. For many small German states, the resulting borders changed the trade-off between the benefits from cooperation with Prussia and the costs of losing political control. Based on GIS data on Central Europe for 1818–1854 we estimate a simple model of the incentives to join an existing customs union. The model can explain the sequence of states joining the Prussian Zollverein extremely well. Moreover we run a counterfactual exercise: if Prussia would have succeeded with her strategy to gain the entire Kingdom of Saxony instead of the western provinces, the Zollverein would not have formed. We conclude that geography can shape institutional change. To put it different, as collateral damage to her intervention at Vienna,”’Britain unified Germany”’. JEL Codes: C31, F13, N73 ∗We would like to thank Robert C. Allen, Nicholas Crafts, Theresa Gutberlet, Theocharis N. Grigoriadis, Ulas Karakoc, Daniel Kreßner, Stelios Michalopoulos, Klaus Desmet, Florian Ploeckl, Kevin H. -

Auction V Iewing

AN AUCTION OF Ancient Coins and Artefacts World Coins and Tokens Islamic Coins The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Monday 30 September 2013 10:00 Free Online Bidding Service AUCTION www.dnw.co.uk Monday 23 September to Thursday 26 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Strictly by appointment only Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 27, 28 and 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Monday 30 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale VIEWING Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or [email protected] Catalogued by Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley, Jim Brown, Tim Wilkes and Nigel Mills In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley or Jim Brown Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Session 1, 10.00 Ancient Coins from the Collection of Dr Paul Lewis.................................................................3001-3025 Ancient Coins from other properties ........................................................................................3026-3084 Ancient Coins – Lots ..................................................................................................................3085-3108 Artefacts ......................................................................................................................................3109-3124 10-minute intermission prior to Session 2 World Coins and Tokens from the Collection formed by Allan -

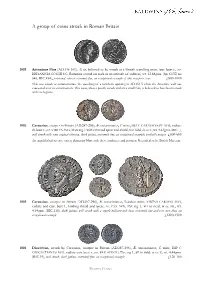

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

Coins and Medals;

CATALOGUE OF A VERY IKTERESTIKG COLLECTION'' OF U N I T E D S T A T E S A N D F O R E I G N C O I N S A N D M E D A L S ; L ALSO, A SMx^LL COLLECTION OF ^JMCIEjMT-^(^REEK AND l^OMAN foiJMg; T H E C A B I N E T O F LYMAN WILDER, ESQ., OF HOOSICK FALLS, N. Y., T O B E S O L D A T A U C T I O N B Y MJSSSBS. BAjYGS . CO., AT THEIR NEW SALESROOMS, A/'os. yjg and ^4.1 Broadway, New York, ON Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, May 21, 23 and 2Ji,, 1879, AT HALF PAST TWO O'CLOCK. C a t a l o g u e b y J o l a n W . H a s e l t i n e . PHILADELPHIA: Bavis & Phnnypackeh, Steam Powee Printers, No. 33 S. Tenth St. 1879. j I I I ih 11 lii 111 ill ill 111 111 111 111 11 1 i 1 1 M 1 1 1 t1 1 1 1 1 1 - Ar - i 1 - 1 2 - I J 2 0 - ' a 4 - - a a 3 2 3 B ' 4 - J - 4 - + . i a ! ! ? . s c c n 1 ) 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 'r r '1' '1' ,|l l|l 1 l-Tp- S t ' A L E O P O n e - S i x t e e n t h o f a n I n c h . -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

A.J.P. Taylor:The Course of German History

The Course of German History A.J.P. Taylor July 27-30, 2015 Taylor does not suffer from as much as he enjoys Germophobia. The book was written just after the end of the War which he sees as the logical conclusion of German destiny. This rather tendentious survey makes for good reading and entertainment, the author generously drops his sarcasms as so many high-explosives and spreads his ’bon mots’ around as artillery fire. The nation of Germany is probably older than the nation of either England and France, due to the formation of the Holy Roman Empire. It can be traced back to Charlemagne, and was of course a feudal contraption of vassals under the nominal authority of the Emperor. The high point of Germany was during the Middle-Ages, according to Taylor. A time of prosperity and local self-government and a proud tradition of independent towns and cities. And also the high-point of the Hanseatic League monopolizing trade on the Baltic. But early on there were two Germanies, the author reminds the reader. The Germany of the West, and the Germany of the East. It is the former with which most westerners are familiar, it is the civilized country of culture and achievement, while the Germany of the East, whom the Slavs would encounter to their peril, was an expansive and brutal power intent on expansion and subjugation, relentlessly and inexorably driving the Slavs eastwards. This ’Drang nach Osten’ is hence something that Taylor identifies as a defining character of the German fate. Luther was a catastrophe for Germany, Taylor claims. -

Economic Geography and Its Effect on the Development of the German

Economic Geography and its Effect on the Development of the German States from the Holy Roman Empire to the German Zollverein (Wirtschaftsgeographie und ihr Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der deutschen Staaten vom Heiligen Romischen¨ Reich bis zum Deutschen Zollverein) DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum politicarum (Doktor der Wirtschaftswissenschaft) eingereicht an der WIRTSCHAFTSWISSENSCHAFTLICHEN FAKULTAT¨ DER HUMBOLDT-UNIVERSITAT¨ ZU BERLIN von THILO RENE´ HUNING M.SC. Pr¨asidentin der Humboldt-Universit¨at zu Berlin: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. Sabine Kunst Dekan der Wirtschaftwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at: Prof. Dr. Daniel Klapper Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Wolf 2. Prof. Barry Eichengreen, Ph.D. Tag des Kolloqiums: 02. Mai 2018 Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Dissertation setzt sich mit dem Einfluß okonomischer¨ Geographie auf die Geschichte des Heiligen Romischen¨ Reichs deutscher Nation bis zum Deutschen Zollverein auseinander. Die Dissertation besteht aus drei Kapiteln. Im ersten Kapitel werden die Effekte von Heterogenitat¨ in der Beobacht- barkeit der Bodenqualitat¨ auf Besteuerung und politischen Institutionen erlautert,¨ theoretisch betrachtet und empirisch anhand von Kartendaten analysiert. Es wird ein statistischer Zusammenhang zwischen Beobachtbarkeit der Bodenqualitat¨ und Große¨ und Uberlebenswahrschenlichkeit¨ von mittelalterlichen Staaten hergestelt. Das zweite Kapitel befasst sich mit dem Einfluß dieses Mechanismus auf die spezielle Geschichte Brandenburg-Preußens, und erlautert¨ die Rolle der Beobachtbarkeut der Bodenqualitat¨ auf die Entwicklung zentraler Institutionen nach dem Dreißigjahrigen¨ Krieg. Im empirischen Teil wird anhand von Daten zu Provinzkontributionen ein statistisch signifikanter Zusammenhang zwischen Bodenqualitat¨ und Besteuerug erst im Laufe des siebzehnten Jahrhundert deutlich. Das dritte Kapitel befasst sich mit dem Einfluß relativer Geographie auf die Grundung¨ des Deutschen Zollvereins als Folge des Wiener Kongresses. -

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined An Analysis ofthe Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies F. A. HAYEK Nohel Laureate 1974 Diseases desperate grown, By desperate appliances are reli'ved, Or not at all. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (Hamlet, Act iv, Scene iii) THIRD EDITION ~~ Published by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1990 First published in October 1976 Second Edition, revised and enlarged, February 1978 Third Edition, with a new Introduction, October 1990 by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 2 Lord North Street, Westminster, London SWIP 3LB © THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1976, 1978, 1990 Hobart Paper (Special) 70 All rights reseroed ISSN 0073-2818 ISBN 0-255 36239-0 Printed in Great Britain by GORON PRO-PRINT CO LTD 6 Marlborough Road, Churchill Industrial Estate, Lancing, W Sussex Text set in 'Monotype' Baskeroille CONTENTS Page PREFACE Arthur Seldon 9 PREFACE TO THE SECOND (EXTENDED) EDITION A.S. 11 AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION 13 A NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION 16 THE AUTHOR 18 INTRODUCTION TO THE THIRD EDITION Geoffrey E. Wood 19 THE PRACTICAL PROPOSAL 23 Free trade in money 23 Proposal more practicable than utopian European currency 23 Free trade in banking 24 Preventing government from concealing depreciation 25 II THE GENERALISATION OF THR UNDERLYING PRINCIPLE 26 Competition in currency not discussed by economists 26 Initial advantages of government monopoly in money 27 III THE ORIGIN OF THE GOVERNMENT PREROGATIVE OF MAKING MONEY 28 Government certificate of metal weight and purity 29 The appearance of paper money 31 -

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars Lecture Set #34 Project of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club Photographed by John Cork & Raymond Reingohl Introduction Trade Dollars in this presentation are grouped into 3 categories • True Trade Dollars • It was intended to circulate in remote areas from its minting source • Accepted Trade Dollars • Trade dollar’s value was highly accepted for trading purposes in distant lands • Examples are the Spanish & Mexican 8 Reales and the Maria Theresa Thaler • Controversial Trade Dollars • A generally accepted dollar but mainly minted to circulate in a nation’s colonies • Examples are the Piastre de Commerce and Neu Guinea 5 Marks This is the Schlick Guldengroschen, commonly known as the Joachimstaler because of the large silver deposits found in Bohemia; now in the Czech Republic. The reverse of the prior two coins. Elizabeth I authorized this Crown This British piece created to be used by the East India Company is nicknamed the “Porticullis Crown” because of the iron grating which protected castles from unauthorized entry. Obverse and Reverse of a Low Countries (Netherlands) silver Patagon, also called an “Albertus Taler.” Crown of the United Amsterdam Company 8 reales issued in 1601 to facilitate trade between the Dutch and the rest of Europe. Crown of the United Company of Zeeland, minted at Middleburg in 1602, similar in size to the 8 reales. This Crown is rare and counterfeits have been discovered to deceive the unwary. The Dutch Leeuwendaalder was minted for nearly a century and began as the common trade coin from a combination of all the Dutch companies which fought each other as well as other European powers. -

False ? Model.Combipageviewmodel

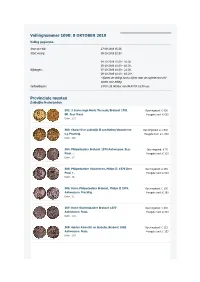

Veilingnummer 1090: 8 OKTOBER 2019 Veiling gegevens Start pre-bid: 27-08-2019 05:26 Start veiling: 08-10-2019 22:50 04-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. 05-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. Kijkdagen: 07-10-2019 10:00 - 21:00. 08-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00*. *tijdens de veiling kunt u kijken naar de objecten tot 100 kavels voor afslag. Ophaaldagen: 14 t/m 18 oktober van 09.00 tot 16.00 uur. Provinciale munten Zuidelijke Nederlanden 502: 2 Souvereign Maria Theresia/Brabant 1761 Openingsbod: € 500 BR. Zeer Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 600 Delm. 215. 503: Chaise D'or Lodewijk II van Malen/Vlaanderen Openingsbod: € 1.500 z.j. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 1.500 Delm. 466. 504: Philipsdaalder Brabant 1574 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 70 Fraai -. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 17. 505: Philipsdaalder Vlaanderen, Philips II. 1575 Zeer Openingsbod: € 150 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 500 Delm. 36. 506: Halve Philipsdaalder Brabant, Philips II 1574, Openingsbod: € 100 Antwerpen. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 180 Delm. 51. 507: Halve Statendaalder Brabant 1577 Openingsbod: € 200 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 200 Delm. 118. 508: Gulden Albrecht en Isabella, Brabant 1602 Openingsbod: € 125 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 155 Delm. 235. 509: Patagon Philips IV, Brabant 1664 Brussel. Zeer Openingsbod: € 90 Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 150 Delm. 285. 510: Halve dukaton Philips IV, Brabant 1638 Openingsbod: € 100 Brussel. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 289. 511: Dukaton Maria Theresia 1754 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 80 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 130 Delm. 375. 512: Halve Dukaton Maria Theresia 1750 Openingsbod: € 50 Antwerpen. Zeer Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 85 Delm. 379. 513: Kronenthaler Franz I 1765 B. -

HARMONY Or HARMONEY

Niklot Kluessendorf Harmony in money – one money for one country ICOMON e-Proceedings (Shanghai, 2010) 4 (2012), pp. 1-5 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org Harmony in money – one money for one country Niklot Klüßendorf Amöneburg, Germany [email protected] This paper discusses the German reforms from 1871 to 1876 for 26 States with different monetary traditions. Particular attention is paid to the strategy of compromise that produced harmony, notwithstanding the different traditions, habits and attitudes to money. Almost everybody found something in the new system that was familiar. The reform included three separate legal elements: coinage, government paper money and banknotes, and was carried out in such a way to avoid upsetting the different parties. Under the common roof of the new monetary unit, traditional and regional elements were preserved, eg in coin denominations, design, and even in the colours of banknotes. The ideas of compromise were helpful to the mental acceptance of the new money. As money and its tradition are rooted in the habits and feelings of the people, the strategy of creating harmony has to be taken into consideration for many monetary reforms. So the German reforms were a good example for the euro that was introduced with a similar spirit for harmony among the participating nations. New currencies need intensive preparation covering political, economic and technical aspects, and even psychological planning. The introduction of the euro was an outstanding example of this. The compromise between national and supranational ideas played an important role during the creation of a single currency for Europe. Euro banknotes, issued by the European Central Bank, demonstrate the supranational idea.