HARMONY Or HARMONEY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Terminal Mesolithic and Early Neolithic Log Boats of Stralsund- Mischwasserspeicher (Hansestadt Stralsund, Fpl

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263238670 The Terminal Mesolithic and Early Neolithic log boats of Stralsund- Mischwasserspeicher (Hansestadt Stralsund, Fpl. 225). Evidence of early waterborne transport on the German Southe... Chapter · January 2009 CITATION READS 1 435 2 authors: Stefanie Klooß Harald Lübke Archäologisches Landesamt Schleswig-Holstein Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie 30 PUBLICATIONS 177 CITATIONS 127 PUBLICATIONS 753 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Untersuchungen und Materialien zur Steinzeit in Schleswig-Holstein und im Ostseeraum View project Archaeology of Hunting View project All content following this page was uploaded by Stefanie Klooß on 20 June 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Forschungsinstitut für Vor- und Frühgeschichte Sonderdruck aus Ronald Bockius (ed.) BETWEEN THE SEAS TRANSFER AND EXCHANGE IN NAUTICAL TECHNOLOGY PROCEEDINGS OF THE ELEVENTH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON BOAT AND SHIP ARCHAEOLOGY MAINZ 2006 ISBSA 11 Hosted by Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Forschungsbereich Antike Schiffahrt, Mainz With support from Gesellschaft der Freunde des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 2009 STEFANIE KLOOSS · HARALD LÜBKE THE TERMINAL MESOLITHIC AND EARLY NEOLITHIC LOGBOATS OF STRALSUND-MISCHWASSERSPEICHER EVIDENCE OF EARLY WATERBORNE TRANSPORT ON THE GERMAN SOUTHERN BALTIC COAST At the German Baltic coast excellent conditions exist for the preservation of archaeological objects, and even for organic material, wood, bark or plant fibre. Due to the worldwide sea level rise and the isostatic land sinking after the Weichselian glaciation, a regular sunken landscape with traces of human dwelling- places and other activities is preserved below the present sea level at the S.W. -

Auction V Iewing

AN AUCTION OF Ancient Coins and Artefacts World Coins and Tokens Islamic Coins The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Monday 30 September 2013 10:00 Free Online Bidding Service AUCTION www.dnw.co.uk Monday 23 September to Thursday 26 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Strictly by appointment only Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 27, 28 and 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Monday 30 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale VIEWING Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or [email protected] Catalogued by Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley, Jim Brown, Tim Wilkes and Nigel Mills In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley or Jim Brown Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Session 1, 10.00 Ancient Coins from the Collection of Dr Paul Lewis.................................................................3001-3025 Ancient Coins from other properties ........................................................................................3026-3084 Ancient Coins – Lots ..................................................................................................................3085-3108 Artefacts ......................................................................................................................................3109-3124 10-minute intermission prior to Session 2 World Coins and Tokens from the Collection formed by Allan -

Coins and Medals;

CATALOGUE OF A VERY IKTERESTIKG COLLECTION'' OF U N I T E D S T A T E S A N D F O R E I G N C O I N S A N D M E D A L S ; L ALSO, A SMx^LL COLLECTION OF ^JMCIEjMT-^(^REEK AND l^OMAN foiJMg; T H E C A B I N E T O F LYMAN WILDER, ESQ., OF HOOSICK FALLS, N. Y., T O B E S O L D A T A U C T I O N B Y MJSSSBS. BAjYGS . CO., AT THEIR NEW SALESROOMS, A/'os. yjg and ^4.1 Broadway, New York, ON Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, May 21, 23 and 2Ji,, 1879, AT HALF PAST TWO O'CLOCK. C a t a l o g u e b y J o l a n W . H a s e l t i n e . PHILADELPHIA: Bavis & Phnnypackeh, Steam Powee Printers, No. 33 S. Tenth St. 1879. j I I I ih 11 lii 111 ill ill 111 111 111 111 11 1 i 1 1 M 1 1 1 t1 1 1 1 1 1 - Ar - i 1 - 1 2 - I J 2 0 - ' a 4 - - a a 3 2 3 B ' 4 - J - 4 - + . i a ! ! ? . s c c n 1 ) 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 'r r '1' '1' ,|l l|l 1 l-Tp- S t ' A L E O P O n e - S i x t e e n t h o f a n I n c h . -

A Monetary History of the Former German Colony of Kiaochou

A MONETARY HISTORY OF THE FORMER GERMAN COLONY OF KIAOCHOU John E. Sandrock After China’s crushing defeat by Great Britain and France in the two Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1858), the Ch’ing dynasty fell into great decline. After both of these events, the Manchu government was forced to sue for peace – the price of which proved to be very dear indeed. Great Britain and France, sensing the total collapse of civil rule in China, placed exorbitant demands upon China in the form of repatriations as laid down in the Treaty of Nanking. These took two distinct forms; the demand for monetary indemnity in silver for expenditures incurred in the war, and for the outright concession of Chinese territory. The Chinese eventually handed over twenty-one million ounces of silver to satisfy the former, and the island of Hong Kong to satisfy the latter. Thus the British territory of Hong Kong was created. This act proved the forerunner of additional demands for territorial concessions on the part of the European powers and Japan, who then proceeded to carve China up into various spheres of influence for commercial exploitation. French territorial ambitions centered upon south China. The British, in addition to their trading port of Hong Kong, sought the right to open additional Yangtze River ports to trade. Russia had ambitions for territorial expansion in the north, where she craved a warm water Russian port on the Liaotung peninsula as well as land in Manchuria. The Japanese, seizing upon the opportunity, laid claim to Korea and the offshore island of Taiwan, which was then renamed Formosa. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined

Denationalisation of Money -The Argument Refined An Analysis ofthe Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies F. A. HAYEK Nohel Laureate 1974 Diseases desperate grown, By desperate appliances are reli'ved, Or not at all. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (Hamlet, Act iv, Scene iii) THIRD EDITION ~~ Published by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1990 First published in October 1976 Second Edition, revised and enlarged, February 1978 Third Edition, with a new Introduction, October 1990 by THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 2 Lord North Street, Westminster, London SWIP 3LB © THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 1976, 1978, 1990 Hobart Paper (Special) 70 All rights reseroed ISSN 0073-2818 ISBN 0-255 36239-0 Printed in Great Britain by GORON PRO-PRINT CO LTD 6 Marlborough Road, Churchill Industrial Estate, Lancing, W Sussex Text set in 'Monotype' Baskeroille CONTENTS Page PREFACE Arthur Seldon 9 PREFACE TO THE SECOND (EXTENDED) EDITION A.S. 11 AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION 13 A NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION 16 THE AUTHOR 18 INTRODUCTION TO THE THIRD EDITION Geoffrey E. Wood 19 THE PRACTICAL PROPOSAL 23 Free trade in money 23 Proposal more practicable than utopian European currency 23 Free trade in banking 24 Preventing government from concealing depreciation 25 II THE GENERALISATION OF THR UNDERLYING PRINCIPLE 26 Competition in currency not discussed by economists 26 Initial advantages of government monopoly in money 27 III THE ORIGIN OF THE GOVERNMENT PREROGATIVE OF MAKING MONEY 28 Government certificate of metal weight and purity 29 The appearance of paper money 31 -

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars Lecture Set #34 Project of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club Photographed by John Cork & Raymond Reingohl Introduction Trade Dollars in this presentation are grouped into 3 categories • True Trade Dollars • It was intended to circulate in remote areas from its minting source • Accepted Trade Dollars • Trade dollar’s value was highly accepted for trading purposes in distant lands • Examples are the Spanish & Mexican 8 Reales and the Maria Theresa Thaler • Controversial Trade Dollars • A generally accepted dollar but mainly minted to circulate in a nation’s colonies • Examples are the Piastre de Commerce and Neu Guinea 5 Marks This is the Schlick Guldengroschen, commonly known as the Joachimstaler because of the large silver deposits found in Bohemia; now in the Czech Republic. The reverse of the prior two coins. Elizabeth I authorized this Crown This British piece created to be used by the East India Company is nicknamed the “Porticullis Crown” because of the iron grating which protected castles from unauthorized entry. Obverse and Reverse of a Low Countries (Netherlands) silver Patagon, also called an “Albertus Taler.” Crown of the United Amsterdam Company 8 reales issued in 1601 to facilitate trade between the Dutch and the rest of Europe. Crown of the United Company of Zeeland, minted at Middleburg in 1602, similar in size to the 8 reales. This Crown is rare and counterfeits have been discovered to deceive the unwary. The Dutch Leeuwendaalder was minted for nearly a century and began as the common trade coin from a combination of all the Dutch companies which fought each other as well as other European powers. -

False ? Model.Combipageviewmodel

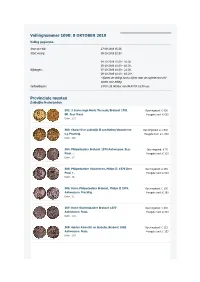

Veilingnummer 1090: 8 OKTOBER 2019 Veiling gegevens Start pre-bid: 27-08-2019 05:26 Start veiling: 08-10-2019 22:50 04-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. 05-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00. Kijkdagen: 07-10-2019 10:00 - 21:00. 08-10-2019 10:00 - 16:00*. *tijdens de veiling kunt u kijken naar de objecten tot 100 kavels voor afslag. Ophaaldagen: 14 t/m 18 oktober van 09.00 tot 16.00 uur. Provinciale munten Zuidelijke Nederlanden 502: 2 Souvereign Maria Theresia/Brabant 1761 Openingsbod: € 500 BR. Zeer Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 600 Delm. 215. 503: Chaise D'or Lodewijk II van Malen/Vlaanderen Openingsbod: € 1.500 z.j. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 1.500 Delm. 466. 504: Philipsdaalder Brabant 1574 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 70 Fraai -. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 17. 505: Philipsdaalder Vlaanderen, Philips II. 1575 Zeer Openingsbod: € 150 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 500 Delm. 36. 506: Halve Philipsdaalder Brabant, Philips II 1574, Openingsbod: € 100 Antwerpen. Prachtig. Hoogste bod: € 180 Delm. 51. 507: Halve Statendaalder Brabant 1577 Openingsbod: € 200 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 200 Delm. 118. 508: Gulden Albrecht en Isabella, Brabant 1602 Openingsbod: € 125 Antwerpen. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 155 Delm. 235. 509: Patagon Philips IV, Brabant 1664 Brussel. Zeer Openingsbod: € 90 Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 150 Delm. 285. 510: Halve dukaton Philips IV, Brabant 1638 Openingsbod: € 100 Brussel. Fraai. Hoogste bod: € 120 Delm. 289. 511: Dukaton Maria Theresia 1754 Antwerpen. Zeer Openingsbod: € 80 Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 130 Delm. 375. 512: Halve Dukaton Maria Theresia 1750 Openingsbod: € 50 Antwerpen. Zeer Fraai +. Hoogste bod: € 85 Delm. 379. 513: Kronenthaler Franz I 1765 B. -

Number 37 May 2000 Euro Coins from Design to Circulation

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Number 37 May 2000 (XURFRLQV From design to circulation © European Communities, 2000. (XURFRLQV )URPGHVLJQWRFLUFXODWLRQ 'LUHFWRUDWH*HQHUDOIRU(FRQRPLFDQG)LQDQFLDO$IIDLUV EURO COINS 7+(/(*$/%$6(6 7KH7UHDW\ 7KHWZR5HJXODWLRQVRI0D\ &5($7,1*7+((852&2,16 &KRRVLQJWKHQDPH &KRRVLQJWKHGHQRPLQDWLRQVRIWKHFRLQV 'HWHUPLQLQJWKHWHFKQLFDOVSHFLILFDWLRQVRIWKHFRLQV &KRRVLQJWKHFRPPRQVLGHRIWKHFRLQV &KRRVLQJWKHQDWLRQDOVLGHRIWKHFRLQV &UHDWLQJFROOHFWRUFRLQV…………………………………………………………………………..16 352'8&,1*7+((852&2,16 'HWHUPLQLQJWKHTXDQWLWLHVWRSURGXFH &RQWUROOLQJTXDOLW\ 3527(&7,1*7+((852&2,16« )LOLQJDFRS\ULJKWRQWKHFRPPRQVLGHV 3UHYHQWLQJDQGVXSSUHVVLQJFRXQWHUIHLWLQJ ,1752'8&,1*7+((852&2,16 )LQDOLVLQJWKHVFKHGXOHIRUWKHLQWURGXFWLRQRIWKHFRLQV 'HILQLQJWKHOHQJWKRIWKHSHULRGRIGXDOFLUFXODWLRQ ,1)250$7,216+((76 1R7KHFKRLFHRIWKHHXURV\PERO««««««««««««««««««««««««« 1R6LWXDWLRQRI0RQDFR9DWLFDQ&LW\DQG6DQ0DULQR« 1R8VHIXO,QWHUQHWOLQNV« 1R$GGUHVVHVDQGFRQWDFWVRIWKHFRLQWHVWLQJFHQWUHV« $11(;(6 $UWLFOH H[D RIWKH7UHDW\HVWDEOLVKLQJWKH(XURSHDQ&RPPXQLW\« &RXQFLO5HJXODWLRQ (& 1RRI0D\RQWKHLQWURGXFWLRQRIWKHHXUR &RXQFLO 5HJXODWLRQ (& 1R RI 0D\ RQ GHQRPLQDWLRQV DQG WHFKQLFDO VSHFLILFDWLRQV RI HXUR FRLQV LQWHQGHGIRUFLUFXODWLRQ««« 2/45 &RXQFLO5HJXODWLRQ (& 1RRI)HEUXDU\DPHQGLQJ5HJXODWLRQ (& 1RRQGHQRPLQDWLRQV DQGWHFKQLFDOVSHFLILFDWLRQVRIHXURFRLQVLQWHQGHGIRUFLUFXODWLRQ««««««««« &RPPLVVLRQ5HFRPPHQGDWLRQRI-DQXDU\FRQFHUQLQJFROOHFWRUFRLQVPHGDOVDQGWRNHQV«« 5HSRUWIURPWKH&ROOHFWRU&RLQ6XEJURXSRIWKH0':*IRUWKH(XUR&RLQ6XEFRPPLWWHHRIWKH()&«« &RXQFLO 'HFLVLRQ RI $SULO H[WHQGLQJ (XURSRO V PDQGDWH -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521632277 - The Logic of Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond Walter Mattli Excerpt More information 1 Introduction 1 The phenomenon of regional integration Regional integration schemes have multiplied in the past few years and the importance of regional groups in trade, money, and politics is increasing dramatically. Regional integration, however, is no new phenomenon. Examples of StaatenbuÈnde, Bundesstaaten, Eidgenossen- schaften, leagues, commonwealths, unions, associations, pacts, confed- eracies, councils and their like are spread throughout history. Many were established for defensive purposes, and not all of them were based on voluntaryassent. This book looks at a particular set of regional integration schemes. The analysis covers cases that involve the voluntary linking in the economic and political domains of two or more formerly independent states to the extent that authorityover keyareas of national policyis shifted towards the supranational level. The ®rst major voluntaryregional integration initiatives appeared in the nineteenth century. In 1828, for example, Prussia established a customs union with Hesse-Darmstadt. This was followed successively bythe Bavaria WuÈrttemberg Customs Union, the Middle German Commercial Union, the German Zollverein, the North German Tax Union, the German MonetaryUnion, and ®nallythe German Reich. This wave of integration spilled over into what was to become Switzer- land when an integrated Swiss market and political union were created in 1848. It also brought economic and political union to Italyin the risorgimento movement. Integration fever again struck Europe in the last decade of the nineteenth century, when numerous and now long- forgotten projects for European integration were concocted. In France, Count Paul de Leusse advocated the establishment of a customs union in agriculture between Germanyand France, with a common tariff bureau in Frankfurt.1 Other countries considered for membership were Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Spain. -

Udl-Juni Vejl2015

UOFICIELLE KURSER VEJLEDENDE - UDEN FORBINDENDE Juni LAND LANDEKODE MØNTENHED a' KURS PR. 100 ENH. AFGHANISTAN AFA AFGHANI 100 PULS 11,17 ALBANIEN ALL LEK 100 QUINDARKA 5,328 ALGERIET DZD ALGIERSK DINAR 100 CENTIMES 6,755 ANDORRA EUR EURO 100 CENT (A) ANGOLA AOA KWANZA 100 IWEI 5,521 ARGENTINA ARS PESO 100 CENTAVOS 73,38 ARMENIEN AMD DRAM 100 LUMA 1,415 ARUBA AWG ARUBA GYLDEN 100 CENT 372,49 ASERBAJDSJAN AZM ASERB.MANAT 100 GOPIK 639,14 AZORERNE EUR EURO 100 CENT (A) BAHAMA ØERNE BSD BAHAMA DOLLAR 100 CENTS 666,75 BAHRAIN BHD BAHRAIN DINAR 1000 FILS 1768,50 BANGLADESH BDT TAKA 100 PAISA 8,577 BARBADOS BBD BARBADOS DOLLAR 100 CENTS 333,37 BELIZE BZD BELIZE DOLLAR 100 CENTS 333,37 BENIN XOF C.F.A. FRANCE 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 BERMUDA BMD BERMUDA DOLLAR 100 CENT 666,75 BHUTAN BTN NGULTRUM 100 CHETRUM 10,47 INDISK RUPEE 1 ) 100 CHETRUM/PAISA BOLIVIA BOB BOLIVIANO 100 CENTAVOS 97,47 BOSNIEN-HERCEGOVINA BAM BOSN.MARK 100 PFENNIG 380,94 BOTSWANA BWP PULA 100 THEBE 67,34 BRASILIEN BRL REAL 100 CENTAVOS 213,59 BRUNEI BND BRUNEI DOLLAR 100 SEN 495,25 BURKINA FASO XOF C.F.A. FRANCE 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 BURUNDI BIF BURUNDI FRANC 100 CENTIMES 0,4305 CAMBODIA KHR RIEL 100 SEN 0,1653 CAMEROUN XAF C.F.A. FRANC 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 CAYMAN ØERNE KYD CAYMAN ISLAND DOLLAR 100 CENT 813,12 CENTRALAFRIKANSKE REP. XAF C.F.A. FRANC 100 CENTIMES 1,1370 CHILE CLP CHILE PESO 100 CENTAVOS 1,0430 COLOMBIA COP COLOMBIA PESO 100 CENTAVOS 0,2582 COMORE ØERNE KMF COMORE FRANCE 100 CENTIMES 1,5250 CONGO XAF C.F.A. -

Explaining the September 1992 ERM Crisis: the Maastricht Bargain and Domestic Politics in Germany, France, and Britain

Explaining the September 1992 ERM Crisis: The Maastricht Bargain and Domestic Politics in Germany, France, and Britain Explaining the September 1992 ERM Crisis: The Maastricht Bargain and Domestic Politics in Germany, France, and Britain Christina R. Sevilla Harvard University Dept. of Government Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Presented at the European Community Studies Association, Fourth Biennial International Conference, May 11-14, 1995, Charleston, SC. Comments welcome. In September of 1992, the seemingly inexorable movement of the European exchange rate mechanism from a system of quasi-fixed exchange rates towards monetary union and ultimately a common currency by the end of the decade was abruptly preempted, perhaps indefinitely. Massive speculative pressure on the eve of the French referendum precipitated the worst crisis in the thirteen- year history of the European Monetary System, resulting in the ejection of the sterling and the lira from the ERM, the devaluation of the peseta, the threat of forced devaluation of several other currencies, including the "hard-core" franc, and the abandonment or near-abandonment of unilateral currency pegs to the system by non-ERM countries. Together with political recriminations and blame-laying between Britain and Germany in the aftermath, the crisis represented a tremendous blow to the goals of political and economic integration recently affirmed by EC member governments in the Maastricht Treaty on European Union in December 1991. Nevertheless, conventional wisdom at the time dictated a more sanguine assessment of the prospects for EMU, in the belief that the strains within the ERM were due to the unfortunate confluence of exceptional circumstances -- the shock of German reunification, a debt-driven recession in Britain, and the uncertainties caused by the Danish and French referendums on Maastricht.