Mitogenomic Diversity in Sacred Ibis Mummies Sheds Light on Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

Behavioural Adaptation of a Bird from Transient Wetland Specialist to an Urban Resident

Behavioural Adaptation of a Bird from Transient Wetland Specialist to an Urban Resident John Martin1,2*, Kris French1, Richard Major2 1 Institute for Conservation Biology and Environmental Management, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia, 2 Terrestrial Ecology, Australian Museum, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Abstract Dramatic population increases of the native white ibis in urban areas have resulted in their classification as a nuisance species. In response to community and industry complaints, land managers have attempted to deter the growing population by destroying ibis nests and eggs over the last twenty years. However, our understanding of ibis ecology is poor and a question of particular importance for management is whether ibis show sufficient site fidelity to justify site-level management of nuisance populations. Ibis in non-urban areas have been observed to be highly transient and capable of moving hundreds of kilometres. In urban areas the population has been observed to vary seasonally, but at some sites ibis are always observed and are thought to be behaving as residents. To measure the level of site fidelity, we colour banded 93 adult ibis at an urban park and conducted 3-day surveys each fortnight over one year, then each quarter over four years. From the quarterly data, the first year resighting rate was 89% for females (n = 59) and 76% for males (n = 34); this decreased to 41% of females and 21% of males in the fourth year. Ibis are known to be highly mobile, and 70% of females and 77% of males were observed at additional sites within the surrounding region (up to 50 km distant). -

Namibia & the Okavango

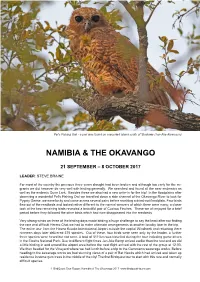

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

The African Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis Aethiopicus)

Oasi di Bolgheri The African sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) A new species for the Bolgheri Bird Sanctuary Historically the distribution of the species has affected the sub Saharan and the North African desert belt, as well as southern Spain and the Middle East. Sighted for the first time in Italy in 1989 in the Regional Park of the Lame Sesia in Piedmont, the species has gradually expanded to the Po valley. The first report of the presence of the species in Bolgheri consisting of 4 individuals was recorded by the WWF guide of the Bolgheri Bird Sanctuary Paola Visicchio during a guided tour on the 8th of November 2014. I confirmed the reporting on the 10th of November 2014 by photographing 12 individuals, including some young, recognizable by the black sooty coloring of the neck and head unlike adults, who are not distinguishable by sex and have a shiny black head and beak. The species was again observed on 14.11.2014 in the marshy pastures of Le Cioccaie (9 individuals) and on the 15th of November during the opening of the Bolgheri Bird Sanctuary visits (4 individuals). The African sacred ibis graze in gregarious form in search of food consisting mainly of invertebrates and small vertebrates, just like the cattle egrets. The curved beak allows them to probe the muddy ground of the bird sanctuary to identify potential prey. The myth of the sacred ibis In the representations of Egyptian hieroglyphics, the deity Thoth is mostly depicted with the mask of a sacred ibis, the large bird of the Nile. -

Birds of Marakele National Park

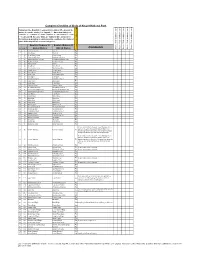

BIRDS OF MARAKELE NATIONAL PARK English (Roberts 6) Old SA No. Rob No. English (Roberts 7) Global Names Names 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich 2 6 Great Crested Grebe Great Crested Grebe 3 8 Little Grebe Dabchick 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant 7 60 African Darter Darter 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern 23 81 Hamerkop Hamerkop 24 83 White Stork White Stork 25 84 Black Stork Black Stork 26 85 Abdim's Stork Abdim's Stork 27 89 Marabou Stork Marabou Stork 28 90 Yellowbilled Stork Yellowbilled Stork 29 91 African Sacred Ibis Sacred Ibis 30 93 Glossy Ibis Glossy Ibis 31 94 Hadeda Ibis Hadeda Ibis 32 95 African Spoonbill African Spoonbill 33 96 Greater Flamingo Greater Flamingo 34 97 Lesser Flamingo Lesser Flamingo 35 99 Whitefaced Duck Whitefaced Duck 36 100 Fulvous Duck Fulvous Duck 37 101 Whitebacked Duck Whitebacked Duck 38 102 Egyptian Goose Egyptian Goose 39 103 South African Shelduck South African Shelduck 40 104 Yellowbilled -

Recent Data on Birds of Kinshasa in Democratic Republic of Congo

Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology A 5 (2015) 218-233 doi: 10.17265/2161-6256/2015.03.011 D DAVID PUBLISHING Recent Data on Birds of Kinshasa in Democratic Republic of Congo Julien Kumanenge Punga1 and Séraphin Ndey Bibuya Ifuta2 1. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Kinshasa, P.O. Box 190, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo 2. Department of Biology, Teaching Higher Institute of Gombe, P.O. Box 3580, Gombe, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo Abstract: The study aimed at understanding the current avifauna characteristics, like composition, species diversity and evolution, in the city of Kinshasa. The study was conducted from 2006 to 2014, using observation, photography and Japanese nets. Results of the study indicate that there are 131 species of birds, which represents 40 families and 16 orders. Avifauna of Kinshasa represents 11% of species of the all country. Among those species, 12 are new. Passerines are the most, representing 86 species and 21 families, and are the most diversified. Few species have extended their geographical distribution and some are migratory. Overtime, avian fauna of Kinshasa region has undergone a lot of changes in its composition and diversity. Horizontal extension of the city associated with the consecutive various changes of the habitats seems to be the principal factors which modulate those characteristics. However, the study found that the majority of these species were under precarious statute of conservation. Key words: Birds, specific diversity, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. 1. Introduction 1.2 Habitat 1.1 Goals of the Study Kinshasa, formerly called Leopoldville, was founded in December 1881 [9] and had a population Birds have been the subject of several studies in the of 5,000 inhabitants in 1884, living on 115 ha with a Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly density of 43.5 inhabitants/ha [10]. -

SOUTH AFRICA: LAND of the ZULU 26Th October – 5Th November 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 A Tropical Birding CUSTOM tour SOUTH AFRICA: LAND OF THE ZULU th th 26 October – 5 November 2015 Drakensberg Siskin is a small, attractive, saffron-dusted endemic that is quite common on our day trip up the Sani Pass Tour Leader: Lisle Gwynn All photos in this report were taken by Lisle Gwynn. Species pictured are highlighted RED. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 INTRODUCTION The beauty of Tropical Birding custom tours is that people with limited time but who still want to experience somewhere as mind-blowing and birdy as South Africa can explore the parts of the country that interest them most, in a short time frame. South Africa is, without doubt, one of the most diverse countries on the planet. Nowhere else can you go from seeing Wandering Albatross and penguins to seeing Leopards and Elephants in a matter of hours, and with countless world-class national parks and reserves the options were endless when it came to planning an itinerary. Winding its way through the lush, leafy, dry, dusty, wet and swampy oxymoronic province of KwaZulu-Natal (herein known as KZN), this short tour followed much the same route as the extension of our South Africa set departure tour, albeit in reverse, with an additional focus on seeing birds at the very edge of their range in semi-Karoo and dry semi-Kalahari habitats to add maximum diversity. KwaZulu-Natal is an oft-underrated birding route within South Africa, featuring a wide range of habitats and an astonishing diversity of birds. -

Kruger Comprehensive

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop -

South Africa – Cape & Kruger III Trip Report 4Th to 14Th December 2015

Best of South Africa – Cape & Kruger III Trip Report 4th to 14th December 2015 Lion by Wayne Jones Trip report by tour leader Wayne Jones RBT Trip Report Best of SA – Cape & Kruger III 2015 2 In the first week of the last month of the year, we began our 10-day exploration of South Africa’s most popular destinations, the Western Cape and Kruger National Park. Everyone had arrived the day before, which afforded us an extra morning – an opportunity we couldn’t pass up! After a scrumptious breakfast overlooking False Bay we followed the coast south along the Cape Peninsula until we reached Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve (Cape Point). We had hardly entered the park when a splendid male Cape Sugarbird grabbed our attention as he sat feeding on big orange “pincushions” and a male Orange- breasted Sunbird sat nicely for pictures before realising he needed another nectar fix. Cape Siskin and Common Buzzard also gave good views nearby, along with a number of spiky, pitch- coloured Black Girdled Lizards. After turning towards Olifantsbos we happened upon four (Cape) Mountain Zebra right alongside the road. This species is not common in the park so we Mountain Zebra by Wayne Jones were very fortunate to have such excellent views of these beauties. Equally beautiful and scarce were the Blesbok (Bontebok) we found closer to the beach. But back to the birds, which were surprisingly plentiful and easy to see, probably thanks to the lack of strong winds that one is normally blasted away by, in the area! Grey-backed and Levaillant’s Cisticolas, Cape Grassbird, Cape Bulbul, Fiscal Flycatcher, Alpine Swift, Rock Kestrel, Peregrine Falcon, White-necked Raven, Karoo Prinia, Malachite Sunbird and Yellow Bishop showed well in the fynbos areas while African Oystercatcher, Greater Crested, Common and Sandwich Terns, Kelp and Hartlaub’s Gulls, Egyptian Goose, White-breasted Cormorant and Sacred Ibis were found along the shoreline. -

Namibia & Botswana

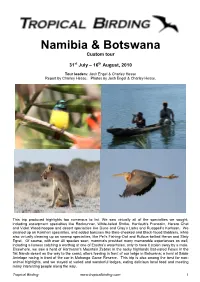

Namibia & Botswana Custom tour 31st July – 16th August, 2010 Tour leaders: Josh Engel & Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Josh Engel & Charley Hesse. This trip produced highlights too numerous to list. We saw virtually all of the specialties we sought, including escarpment specialties like Rockrunner, White-tailed Shrike, Hartlaub‟s Francolin, Herero Chat and Violet Wood-hoopoe and desert specialties like Dune and Gray‟s Larks and Rueppell‟s Korhaan. We cleaned up on Kalahari specialties, and added bonuses like Bare-cheeked and Black-faced Babblers, while also virtually cleaning up on swamp specialties, like Pel‟s Fishing-Owl and Rufous-bellied Heron and Slaty Egret. Of course, with over 40 species seen, mammals provided many memorable experiences as well, including a lioness catching a warthog at one of Etosha‟s waterholes, only to have it stolen away by a male. Elsewhere, we saw a herd of Hartmann‟s Mountain Zebras in the rocky highlands Bat-eared Foxes in the flat Namib desert on the way to the coast; otters feeding in front of our lodge in Botswana; a herd of Sable Antelope racing in front of the car in Mahango Game Reserve. This trip is also among the best for non- animal highlights, and we stayed at varied and wonderful lodges, eating delicious local food and meeting many interesting people along the way. Tropical Birding www.tropicalbirding.com 1 The rarely seen arboreal Acacia Rat (Thallomys) gnaws on the bark of Acacia trees (Charley Hesse). 31st July After meeting our group at the airport, we drove into Nambia‟s capital, Windhoek, seeing several interesting birds and mammals along the way. -

Arabian Peninsula

THE CONSERVATION STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE BREEDING BIRDS OF THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Compiled by Andy Symes, Joe Taylor, David Mallon, Richard Porter, Chenay Simms and Kevin Budd ARABIAN PENINSULA The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM - Regional Assessment About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature-based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with almost 1,300 government and NGO Members and more than 15,000 volunteer experts in 185 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by almost 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of around 7,500 experts. SSC advises IUCN and its members on the wide range of technical and scientific aspects of species conservation, and is dedicated to securing a future for biodiversity. SSC has significant input into the international agreements dealing with biodiversity conservation. About BirdLife International BirdLife International is the world’s largest nature conservation Partnership. BirdLife is widely recognised as the world leader in bird conservation. -

SIS Conservation Publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group

SIS Conservation Publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group ISSUE 1, 2019 SPECIAL ISSUE: GLOSSY IBIS ECOLOGY & CONSERVATION Editors-in-chief: K.S. Gopi Sundar and Luis Santiago Cano Alonso Guest Editor for Special Issue: Simone Santoro ISBN 978-2-491451-01-1 SIS Conservation Piotr Tryjanowski, Poland Publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis & Spoonbill Abdul J. Urfi, India Specialist Group Amanda Webber, United Kingdom View this journal online at https://storkibisspoonbill.org/sis-conservation- SPECIAL ISSUE GUEST EDITOR publications/ Simone Santoro PhD | University Pablo Olavide | Spain AIMS AND SCOPE Special Issue Editorial Board Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Conservation (SISC) is a peer- Mauro Fasola PhD | Università di Pavia| Italy reviewed publication of the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Ricardo Lima PhD | University of Lisbon | Portugal Spoonbill Specialist Group. SISC publishes original Jocelyn Champagnon PhD | Tour du Valat| France content on the ecology and conservation of both wild and Alejandro Centeno PhD | University of Cádiz | Spain captive populations of SIS species worldwide, with the Amanda Webber PhD | Bristol Zoological Society| UK aim of disseminating information to assist in the Frédéric Goes MSc | Osmose |France management and conservation of SIS (including Shoebill) André Stadler PhD | Alpenzoo Innsbruck |Austria populations and their habitats worldwide. We invite Letizia Campioni PhD | MARE, ISPA|Portugal anyone, including people who are not members of the Piotr Tryjanowski PhD | Poznań University of Life SIS-SG, to submit manuscripts. Sciences| Poland The views expressed in this publication are those of the Phillippe Dubois MSc | Independent Researcher | France authors and do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, nor Catherine King MSc | Zoo Lagos |Portugal the IUCN SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group.