The Spreading of the Invasive Sacred Ibis in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IAGNBI Newsletter 3 July 2004

International Advisory Group for Northern Bald Ibis newsletter 3 July 2004 An update on current projects involving wild and captive Northern Bald Ibis Edited by Christiane Boehm 1. What is IAGNBI ? page 1.1. IAGNBI: Its role and committee 4 1.2. Statement on the conservation priorities 5 2. Ongoing research and release projects: updates of 2003 2.1. The Austrian Bald Ibis Migration 2002-2004: A story of success and failure Johannes Fritz 7 2.2. News from the Gruenau semi-wild colony of the Waldrapp Ibis Kurt Kotrschal 14 2.3. A study of different release techniques for a captive population of Northern Bald Ibis (Geronticus eremita) in the region of La Janda (Cádiz, Southern Spain) Miguel A. Quevedo, Iñigo Sánchez, José M. Aguilar & Mariano Cuadrado 20 2.4. Waldrapp Project „Bschar el Kh-ir“ in Ain Tijja in Morocco Hans Peter Mueller 27 3. Wild colonies: updates of the programmes, situation, projects 3.1. The Bald Ibis in Souss Massa Region ( Morocco) Mohammed El Bekkay, Widade Oubrou 30 3.2. First month of Ibis protection programme 2004 in Syria: never a dull moment… Gianluca Serra 32 4. Meeting reports 4.1 Report on the Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita: Conservation and Reintroduction Workshop, Innsbruck July 2003 Christiane Boehm 34 4.2. Species Action Planning Meetings for the Northern Bald Ibis, Madrid, Spain, January 2004 Species Action Planning Meetings for the Southern Bald Ibis, Wakkastroom, South Africa, November 2003 Chris Bowden 37 4.3. The status of the Northern Bald Ibis within the EAZA Ciconiiformes and Phoenicopteriformes Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) Cathrine King 38 5. -

156 Glossy Ibis

Text and images extracted from Marchant, S. & Higgins, P.J. (co-ordinating editors) 1990. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to ducks; Part B, Australian pelican to ducks. Melbourne, Oxford University Press. Pages 953, 1071-1 078; plate 78. Reproduced with the permission of Bird life Australia and Jeff Davies. 953 Order CICONIIFORMES Medium-sized to huge, long-legged wading birds with well developed hallux or hind toe, and large bill. Variations in shape of bill used for recognition of sub-families. Despite long legs, walk rather than run and escape by flying. Five families of which three (Ardeidae, Ciconiidae, Threskiornithidae) represented in our region; others - Balaenicipitidae (Shoe-billed Stork) and Scopidae (Hammerhead) - monotypic and exclusively Ethiopian. Re lated to Phoenicopteriformes, which sometimes considered as belonging to same order, and, more distantly, to Anseriformes. Behavioural similarities suggest affinities also to Pelecaniformes (van Tets 1965; Meyerriecks 1966), but close relationship not supported by studies of egg-white proteins (Sibley & Ahlquist 1972). Suggested also, mainly on osteological and other anatomical characters, that Ardeidae should be placed in separate order from Ciconiidae and that Cathartidae (New World vultures) should be placed in same order as latter (Ligon 1967). REFERENCES Ligon, J.D. 1967. Occas. Pap. Mus. Zool. Univ. Mich. 651. Sibley, C. G., & J.E. Ahlquist. 1972. Bull. Peabody Mus. nat. Meyerriecks, A.J. 1966. Auk 83: 683-4. Hist. 39. van Tets, G.F. 1965. AOU orn. Monogr. 2. 1071 Family PLATALEIDAE ibises, spoonbills Medium-sized to large wading and terrestial birds. About 30 species in about 15 genera, divided into two sub families: ibises (Threskiornithinae) and spoonbills (Plataleinae); five species in three genera breeding in our region. -

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

Ardea Cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds)

UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Ardea cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Grey heron, Ardea cinerea. [http://www.google.tt/imgres?imgurl=http://www.bbc.co.uk/lancashire/content/images/2006/06/15/grey_heron, downloaded 14 November 2012] TRAITS. Grey herons are large birds that can be 90-100cm tall and an adult could weigh in at approximately 1.5 kg. They are identified by their long necks and very powerful dagger like bills (Briffett 1992). They have grey plumage with long black head plumes and their neck is white with black stripes on the front. In adults the forehead sides of the head and the centre of the crown are white. In flight the neck is folded back with the wings bowed and the flight feathers are black. Each gender looks alike except for the fact that females have shorter heads (Seng and Gardner 1997). The juvenile is greyer without black markings on the head and breast. They usually live long with a life span of 15-24 years. ECOLOGY. The grey heron is found in Europe, Asia and Africa, and has been recorded as an accidental visitor in Trinidad. Grey herons occur in many different habitat types including savannas, ponds, rivers, streams, lakes and temporary pools, coastal brackish water, wetlands, marsh and swamps. Their distribution may depend on the availability of shallow water (brackish, saline, fresh, flowing and standing) (Briffett 1992). They prefer areas with tall trees for nesting UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour (arboreal rooster and nester) but if trees are unavailable, grey herons may roost in dense brush or undergrowth. -

IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2

IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2 Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group Djerba Island, Tunisia, 14th - 18th November 2018 Editors: Jocelyn Champagnon, Jelena Kralj, Luis Santiago Cano Alonso and K. S. Gopi Sundar Editors-in-Chief, Special Publications, IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group K.S. Gopi Sundar, Co-chair IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Luis Santiago Cano Alonso, Co-chair IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Invited Editors for this issue Jocelyn Champagnon, Tour du Valat, Research Institute for the Conservation of Mediterranean Wetlands, Arles, France Jelena Kralj, Institute of Ornithology, Zagreb, Croatia Expert Review Board Hichem Azafzaf, Association “les Amis des Oiseaux » (AAO/BirdLife Tunisia), Tunisia Petra de Goeij, Royal NIOZ, the Netherlands Csaba Pigniczki, Kiskunság National Park Directorate, Hungary Suggested citation of this publication: Champagnon J., Kralj J., Cano Alonso, L. S. & Sundar, K. S. G. (ed.) 2019. Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group. IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2. Arles, France. ISBN 978-2-491451-00-4. Recommended Citation of a chapter: Marion L. 2019. Recent trends of the breeding population of Spoonbill in France 2012- 2018. Pp 19- 23. In: Champagnon J., Kralj J., Cano Alonso, L. S. & Sundar, K. S. G. (ed.) Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group. IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2. Arles, France. INFORMATION AND WRITING DISCLAIMER The information and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors. -

The Grey Heron

Bird Life The Grey Heron t is quite likely that if someone points out a grey heron to you, I you will remember it the next time you see it. The grey heron is a tall bird, usually about 80cm to 1m in height and is common to inland waterways and coasts. Though the grey heron has a loud “fraank” call, it can most often be seen standing silently in shallow water with its long neck outstretched, watching the water for any sign of movement. The grey heron is usually found on its own, although some may feed close together. Their main food is fish, but they will take small mammals, insects, frogs and even young birds. Because of their habit of occasionally taking young birds, herons are not always popular and are often driven away from a feeding area by intensive mobbing. Mobbing is when smaller birds fly aggressively at their predator, in this case the heron, in order to defend their nests or their lives. Like all herons, grey herons breed in a colony called a heronry. They mostly nest in tall trees and bushes, but sometimes they nest on the ground or on ledge of rock by the sea. Nesting starts in February,when the birds perform elaborate displays and make noisy callings. They lay between 3-5 greenish-blue eggs, often stained white by the birds’ droppings. Once hatched, the young © Illustration: Audrey Murphy make continuous squawking noises as they wait to be fed by their parents. And though it doesn’t sound too pleasant, the parent Latin Name: Ardea cinerea swallows the food and brings it up again at the nest, where the Irish Name: Corr réisc young put their bills right inside their parents mouth in order to Colour: Grey back, white head and retrieve it! neck, with a black crest on head. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

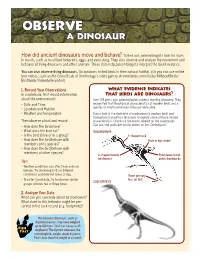

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update

Secretariat provided by the Workshop 3 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Doc TC 8.25 21 February 2008 8th MEETING OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE 03 - 05 March 2008, Bonn, Germany ___________________________________________________________________________ Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update Authors A.N. Banks, L.J. Wright, I.M.D. Maclean, C. Hann & M.M. Rehfisch February 2008 Report of work carried out by the British Trust for Ornithology under contract to AEWA Secretariat © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................5 List of Figures.........................................................................................................................................7 List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................................9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................11 RECOMMENDATIONS .....................................................................................................................13 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................15 -

Wood-Stork-2005.Pdf

WOOD STORK Mycteria americana Photo of adult wood stork in landing posture and chicks in Close-up photo of adult wood stork. nest. Photo courtesy of USFWS/Photo by George Gentry Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. FAMILY: Ciconiidae STATUS: Endangered - U.S. Breeding Population (Federal Register, February 28, 1984) [Service Proposed for status upgrade to Threatened, December 26, 2013] DESCRIPTION: Wood storks are large, long-legged wading birds, about 45 inches tall, with a wingspan of 60 to 65 inches. The plumage is white except for black primaries and secondaries and a short black tail. The head and neck are largely unfeathered and dark gray in color. The bill is black, thick at the base, and slightly decurved. Immature birds have dingy gray feathers on their head and a yellowish bill. FEEDING HABITS: Small fish from 1 to 6 inches long, especially topminnows and sunfish, provide this bird's primary diet. Wood storks capture their prey by a specialized technique known as grope-feeding or tacto-location. Feeding often occurs in water 6 to 10 inches deep, where a stork probes with the bill partly open. When a fish touches the bill it quickly snaps shut. The average response time of this reflex is 25 milliseconds, making it one of the fastest reflexes known in vertebrates. Wood storks use thermals to soar as far as 80 miles from nesting to feeding areas. Since thermals do not form in early morning, wood storks may arrive at feeding areas later than other wading bird species such as herons.