Script Unit 3.6 (Crystal Classes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Name

MINERALS SORTED BY NAME Here is an alphabetical list of minerals discussed on this site. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). APATITE Crystal system: hexagonal. Fracture: conchoidal. Color: red, brown, white. Hardness: 5.0. Luster: opaque or semitransparent. Specific gravity: 3.1. Apatite, also called cellophane, occurs in peridotites in eastern and western Kentucky. A microcrystalline variety of collophane found in northern Woodford County is dark reddish brown, porous, and occurs in phosphatic beds, lenses, and nodules in the Tanglewood Member of the Lexington Limestone. Some fossils in the Tanglewood Member are coated with phosphate. Beds are generally very thin, but occasionally several feet thick. The Woodford County phosphate beds were mined during the early 1900s near Wallace, Ky. BARITE Crystal system: orthorhombic. Cleavage: often in groups of platy or tabular crystals. Color: usually white, but may be light shades of blue, brown, yellow, or red. Hardness: 3.0 to 3.5. Streak: white. Luster: vitreous to pearly. Specific gravity: 4.5. Tenacity: brittle. Uses: in heavy muds in oil-well drilling, to increase brilliance in the glass-making industry, as filler for paper, cosmetics, textiles, linoleum, rubber goods, paints. Barite generally occurs in a white massive variety (often appearing earthy when weathered), although some clear to bluish, bladed barite crystals have been observed in several vein deposits in central Kentucky, and commonly occurs as a solid solution series with celestite where barium and strontium can substitute for each other. Various nodular zones have been observed in Silurian–Devonian rocks in east-central Kentucky. -

Washington State Minerals Checklist

Division of Geology and Earth Resources MS 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington State 360-902-1450; 360-902-1785 fax E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/geology Minerals Checklist Note: Mineral names in parentheses are the preferred species names. Compiled by Raymond Lasmanis o Acanthite o Arsenopalladinite o Bustamite o Clinohumite o Enstatite o Harmotome o Actinolite o Arsenopyrite o Bytownite o Clinoptilolite o Epidesmine (Stilbite) o Hastingsite o Adularia o Arsenosulvanite (Plagioclase) o Clinozoisite o Epidote o Hausmannite (Orthoclase) o Arsenpolybasite o Cairngorm (Quartz) o Cobaltite o Epistilbite o Hedenbergite o Aegirine o Astrophyllite o Calamine o Cochromite o Epsomite o Hedleyite o Aenigmatite o Atacamite (Hemimorphite) o Coffinite o Erionite o Hematite o Aeschynite o Atokite o Calaverite o Columbite o Erythrite o Hemimorphite o Agardite-Y o Augite o Calciohilairite (Ferrocolumbite) o Euchroite o Hercynite o Agate (Quartz) o Aurostibite o Calcite, see also o Conichalcite o Euxenite o Hessite o Aguilarite o Austinite Manganocalcite o Connellite o Euxenite-Y o Heulandite o Aktashite o Onyx o Copiapite o o Autunite o Fairchildite Hexahydrite o Alabandite o Caledonite o Copper o o Awaruite o Famatinite Hibschite o Albite o Cancrinite o Copper-zinc o o Axinite group o Fayalite Hillebrandite o Algodonite o Carnelian (Quartz) o Coquandite o o Azurite o Feldspar group Hisingerite o Allanite o Cassiterite o Cordierite o o Barite o Ferberite Hongshiite o Allanite-Ce o Catapleiite o Corrensite o o Bastnäsite -

Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals

AppendixA __________ Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals 325 Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals J. B. Lyons, S. A. Morse, and R. E. Stoiber Distinguishing Characteristics Chemical XI. System and Indices Birefringence "Characteristically parallel, but Mineral Composition Best Cleavage Sign,2V and Relief and Color see Fig. 13-3. A. High Positive Relief Zircon ZrSiO. Tet. (+) 111=1.940 High biref. Small euhedral grains show (.055) parallel" extinction; may cause pleochroic haloes if enclosed in other minerals Sphene CaTiSiOs Mon. (110) (+) 30-50 13=1.895 High biref. Wedge-shaped grains; may (Titanite) to 1.935 (0.108-.135) show (110) cleavage or (100) Often or (221) parting; ZI\c=51 0; brownish in very high relief; r>v extreme. color CtJI\) 0) Gamet AsB2(SiO.la where Iso. High Grandite often Very pale pink commonest A = R2+ and B = RS + 1.7-1.9 weakly color; inclusions common. birefracting. Indices vary widely with composition. Crystals often euhedraL Uvarovite green, very rare. Staurolite H2FeAI.Si2O'2 Orth. (010) (+) 2V = 87 13=1.750 Low biref. Pleochroic colorless to golden (approximately) (.012) yellow; one good cleavage; twins cruciform or oblique; metamorphic. Olivine Series Mg2SiO. Orth. (+) 2V=85 13=1.651 High biref. Colorless (Fo) to yellow or pale to to (.035) brown (Fa); high relief. Fe2SiO. Orth. (-) 2V=47 13=1.865 High biref. Shagreen (mottled) surface; (.051) often cracked and altered to %II - serpentine. Poor (010) and (100) cleavages. Extinction par- ~ ~ alleL" l~4~ Tourmaline Na(Mg,Fe,Mn,Li,Alk Hex. (-) 111=1.636 Mod. biref. -

The Structure of Hemimorphite

Zeitschrift fUr Kristallographie, Bd. 113, S. 23-29 (1960) The structure of hemimorphite By G. A. BAHCLAY and E. G. Cox Department of Inorganic and Structural Chemistry University of Leeds With 1 figure (Received June 16, 1959) Auszug Die Struktur von Kieselzinkerz, Zn4Si207(OH)2. H20, wurde auf Grund von hkO- und Okl-Projektionen der Elektronendichte neu bestimmt. Das SiP7-Ion besteht aus zwei Si04-Tetraedern mit einem gemeinsamen Sauerstoff- atom; der Si-O-Si-Winkel ist 133°, der Si-O-Abstand vom gemeinsamen O-Atom 1,72 A; die ubrigen Si-O-Abstande sind 1,60 und 1,62 A. Nach vorlaufigen Ergebnissen einer gemeinsam mit H. LYNTON angestellten Untersuchung hat der Thortveitit, Sc2Si207, nicht die Symmetrie 21m und ist cler Winkel Si-O-Si entgegen fruheren Annahmen kein rechter. Abstract The structure of hemimorphite, Zn4(OH)2Si207 . H20, has been redetermined by means of hkO and Okl electron-density projections. The Si207 ion consists of two Si04 tetrahedra with a shared corner; the Si-O-Si angle is 133° and the Si-O distances are 1.72 A (central) and 1.60, 1.62 A (peripheral). Preliminary results for thortveitite, Sc2Si207, (with H. LYNTON) show that the crystals do not have 21m symmetry and that the Si-O-Si angle is not 1800 as formerly supposed. Introduction Earlier investigations of hemimorphite, Zn4(OH)2Si207. H20 (ITo and WEST, 1932), and thortveitite, Sc2Si207 (ZACHARIASEN, 1930), in- dicated linear Si-O-Si bonds in the pyrosilicate groups. On the other hand in the melilites (WARREN, 1930; WARREN and TRAUTZ, 1931), lawsonite (WICKMAN, 1947), tilleyite (SMITH, 1953) and epidote (ITO, MORIMOTOand SADANAGA,1954) the reported Si-O-Si angles range from 131 ° to 165 0; moreover in X207 groups of other kinds the X-O-X angle is usually considerably less than 180°. -

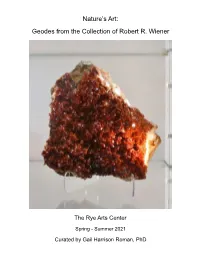

Nature's Art: Geodes from the Collection of Robert R. Wiener

Nature’s Art: Geodes from the Collection of Robert R. Wiener The Rye Arts Center Spring - Summer 2021 Curated by Gail Harrison Roman, PhD A Tribute to Robert R. Wiener The Rye Arts Center extends its gratitude and love to Bob Wiener: Humanitarian, Connoisseur, Collector, Scholar, Educator, Cherished Friend Front cover: Vanadite, Morocco Back cover: Malachite, Congo 1 NATURE’S ART: GEODES FROM THE COLLECTION OF ROBERT R. WIENER Guiding Light of The Rye Arts Center Robert R. Wiener exemplifies the Mission of The Rye Arts Center. He is a supporter of cultural endeavors for all and a staunch believer in extending the educational value of the arts to underserved populations. His largesse currently extends to the Center by his sharing geodes with us. This is the latest chapter of his enduring support that began thirty-five years ago. Bob is responsible for saving 51 Milton Road by spearheading in 1986 the movement to prevent the city’s demolition of our home. He then led the effort to renovate the building that we now occupy. As a member of the RAC Board in the 1980s and 1990s, Bob helped guide the Center through its early years of expansion and success. His efforts have enabled RAC to become a beacon of the arts for the local community and beyond it. Bob has joined with RAC to place cases of his geodes in area schools, where they attract excited attention from children and adults alike. Bob’s maxim is “The purpose of life is to give back.” Led and inspired by Bob, The Wiener Family Philanthropy supports dozens of organizations devoted to the arts, community initiatives, education, health care, and positive youth empowerment. -

Example of Ore Characterization by the Use of Automated Mineralogical Analyses Using Mineralogic Mining (ZEISS) Technology: Results on the Hakkari Samples (Turkey)

©2016 Society of Economic Geologists, Inc. SEG-MJD 2016 Conference Example of Ore Characterization by the Use of Automated Mineralogical Analyses Using Mineralogic Mining (ZEISS) Technology: Results on the Hakkari Samples (Turkey) Licia Santoro,1,* Richard Herrington,1 and Maria Boni2 1Natural History Museum, Earth Sciences Department, Cromwell Rd, SW7 5BD London, UK 2Dipartimento Scienze della Terra, dell’Ambiente e delle Risorse, Università di Napoli Federico II, Via Mezzocannone 8, 80134 Napoli, Italy *Corresponding author: e-mail, [email protected] The Hakkari Zinc Project is a supergene nonsulfide Zn>>Pb deposit located in the southeast of Turkey. Total resources estimated consist of 10 Mt at 15% Zn. The ore concentrations mainly consist of oxidized Zn minerals (smithsonite and hemimorphite) derived from the weathering of sulfides, hosted in shallow-water Jurassic limestone. This preliminary study is focused on the mineralogical and petrographic characterization of four Hakkari samples in terms of quantitative modal mineralogy and average mineral association. The four samples were taken from different oxidation zones representative of the deposit, in order to characterize and quantify all the occurring mineral phases. The analyses were carried out using a new generation of automated mineralogical analysis systems known as “Mineralogic Mining” (ZEISS), which utilizes modern quantitative EDS technology to allow minerals to be classified based on the % element abundance (stoichiometry). Previous QEMSCAN (FEI) analyses for the same four samples of the Hakkari mineralization provided a strong basis for the Mineralogic routine, and were used to assess the accuracy and the capabilities of the Mineralogic system. Mineralogic Mining was able to build high-resolution maps and to clearly identify and quantify the major economic phases, such as smithsonite and hemimorphite (up to ~58 and ~67 wt %, respectively, in the analyzed samples), and gangue phases such as goethite (up to 38 wt %). -

Solubility of Hemimorphite in Ammonium Sulfate Solution at 25 °C

Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 23(2013) 2160−2165 Solubility of hemimorphite in ammonium sulfate solution at 25 °C Qin-xiang LI, Hui-ping HU, De-wen ZENG, Qi-yuan CHEN School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China Received 7 September 2012; accepted 20 November 2012 Abstract: The solubility of natural hemimorphite in ammonium sulfate solution was measured by isothermal solution method at 25 °C and the dissolved residue of hemimorphite was investigated by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) methods. The results show that zinc and silica in hemimorphite simultaneously dissolve in ammonium sulfate solution. The solubility of zinc in solution increases rapidly from 4.5381 mmol/kg in 0.5469 mol/kg ammonium sulfate solution to 11.5083 mmol/kg in 3.7038 mol/kg ammonium sulfate solution. The solubility of silica in solution increases slowly from 2.5509 mmol/kg in 0.5469 mol/kg ammonium sulfate solution to 7.2891 mmol/kg in 3.7038 mol/kg ammonium sulfate solution. The dissolved residue is the characteristic of hemimorphite Zn4Si2O7(OH)2·H2O based on the results of the XRD, SEM and FTIR. Thus, no phase transition occurs in the dissolution process of hemimorphite in ammonium sulfate solution. Key words: hemimorphite; ammonium sulfate; silicic acid; solubility published as “the Schnabel Process” in 1880, which 1 Introduction pre-dated the better-known applications of ammoniacal leaching to copper and nickel by 30 years or more [3]. As the primary source of zinc, oxidized zinc ores Extensive works have studied on the application to a are the main source of zinc metal after nature sulfide ores specific feedstock, mainly non-silica minerals such as are steadily getting depleted. -

Leaching and Solvent Extraction Purification of Zinc from Mehdiabad

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Leaching and solvent extraction purifcation of zinc from Mehdiabad complex oxide ore Faraz Soltani1, Hossna Darabi2, Reza Aram3 & Mahdi Ghadiri4,5* An integrated hydrometallurgical process was used for the zinc leaching and purifcation from a zinc ore containing 9.75 wt% zinc. The zinc minerals in the ore were hemimorphite, willemite, and calcophanite. Main gangue minerals were quartz, goethite, hematite, and calcite. Central composite design (CCD) method was used to design leaching experiments and the optimum conditions were found as follows: 30% of solid fraction, 22.05% sulphuric acid concentration, and the leaching temperature of 45 °C. The PLS containing 35.07 g/L zinc, 3.16 g/L iron, and 4.58 g/L manganese impurities was produced. A special purifcation process including Fe precipitation and Zn solvent extraction was implemented. The results showed that after precipitation of iron, Zn extraction of 88.5% was obtained with the 2 stages extraction system composed of 30 vol% D2EHPA as extractant. The overall Zn recovery from the ore was 71.44%. Therefore, an appropriate solution containing 16.6 g/L Zn, 0.05 g/L Fe, and 0.11 g/L Mn was prepared for the electro-winning unit without using the roasting and calcination steps (conventional method), which result in environmental pollution. Te importance of zinc oxide ores processing such as carbonate and silicates minerals have increased because of the depletion of zinc sulphide ores and the restriction on sulphur emissions during their processing 1–6. Te zinc oxide ores usually contain several diferent minerals including zincite (ZnO), smithsonite (ZnCO 3), hydrozincite 2 (2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)), hemimorphite (Zn 4Si2O7(OH)2·H2O), and willemite (Zn 2SiO4) . -

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Group

MINERALS SORTED BY MINERAL GROUP Most minerals are chemically classified as native elements, sulfides, sulfates, oxides, silicates, carbonates, phosphates, halides, nitrates, tungstates, molybdates, arsenates, or vanadates. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). NATIVE ELEMENTS (DIAMOND, SULFUR, GOLD) Native elements are minerals composed of only one element, such as copper, sulfur, gold, silver, and diamond. They are not common in Kentucky, but are mentioned because of their appeal to collectors. DIAMOND Crystal system: isometric. Cleavage: perfect octahedral. Color: colorless, pale shades of yellow, orange, or blue. Hardness: 10. Specific gravity: 3.5. Uses: jewelry, saws, polishing equipment. Diamond, the hardest of any naturally formed mineral, is also highly refractive, causing light to be split into a spectrum of colors commonly called play of colors. Because of its high specific gravity, it is easily concentrated in alluvial gravels, where it can be mined. This is one of the main mining methods used in South Africa, where most of the world's diamonds originate. The source rock of diamonds is the igneous rock kimberlite, also referred to as diamond pipe. A nongem variety of diamond is called bort. Kentucky has kimberlites in Elliott County in eastern Kentucky and Crittenden and Livingston Counties in western Kentucky, but no diamonds have ever been discovered in or authenticated from these rocks. A diamond was found in Adair County, but it was determined to have been brought in from somewhere else. SULFUR Crystal system: orthorhombic. Fracture: uneven. Color: yellow. Hardness 1 to 2. -

New Mexico Mineral Symposium Abstracts 2002

Abstracts NEVADA 80 Laramie Cheyenne WYOMING Wendover 76 New Mexico Mineral Symposium Salt Lake City UTAH COLORADO 25 The Twenty-Third Annual New Mexico Min- eral Symposium was held November 9 and 10, 6 Denver 2002, at New Mexico Institute of Mining and 6 Ely 70 Technology, Socorro. Following are abstracts 50 from all talks given at the symposium. 6 Grand Junction 70 4 550 Colorado Springs 24 Pueblo 191 RECOVERY OF THE 17 TON COPPER BOUL- 15 93 DER FROM LAKE SUPERIOR, by Bob Bar- 666 ron, Department of Geological and Mining 5 160 Alamosa Engineering and Sciences, Michigan Tech Uni- Durango 285 versity, 1400 Townsend Dr., Houghton, MI 64 OK 49931, [email protected] ARIZONA NEW MEXICO 87 666 84 Springer For well over a century, the Keweenaw Peninsu- 54 la has served as a home to a multi-billion-dollar 191 copper industry. The roots of mining go back Santa Fe Gallup several thousand years when Native Americans TEXAS 40 Flagstaff 40 first discovered the nearly pure copper and sil- Kingman ver deposited in fissure veins cutting across the 666 Albuquerque Keweenaw Peninsula. Along the sparsely vege- 180 Clovis CA 60 tated shores of Lake Superior and inland lakes 17 54 of the post-glacial period, the Native Americans 60 6 Socorro mined the red metal for possibly 10,000 yrs. The Phoenix 1 380 malleable copper was easily shaped into tools 10 Globe 666 Roswell 180 70 and other valued implements and was traded 25 Silver across North America and perhaps beyond. 70 Alamogordo City As an avid scuba diver and mineral collector 8 Hobbs 3 7 for over 25 yrs, I was drawn to Lake Superior Las Cruces Carlsbad because mineral collecting for fine specimens on Tucson 10 2 the Keweenaw was becoming an activity of the Deming 19 180 20 past. -

Behavior of Zn-Bearing Phases in Base Metal Slag from France and Poland: a Mineralogical Approach for Environmental Purposes

Journal of Geochemical Exploration 136 (2014) 1–13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Geochemical Exploration journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jgeoexp Behavior of Zn-bearing phases in base metal slag from France and Poland: A mineralogical approach for environmental purposes Maxime Vanaecker a, Alexandra Courtin-Nomade a,⁎,HubertBrila, Jacky Laureyns b,Jean-FrançoisLenaina a Université de Limoges, GRESE, E.A. 4330, IFR 145 GEIST, F.S.T., 123 Avenue A. Thomas, 87060 Limoges Cedex, France b Université de Lille 1, USTL, LASIR, C5, BP 69, 59652 Villeneuve d'Ascq Cedex, France article info abstract Article history: Slag samples from three pyrometallurgical sites (two in France, one in Poland) were studied for their Zn-phase con- Received 18 February 2013 tent, evolution and potential release of metals over time. Mineral assemblages were observed and analyzed using Accepted 3 September 2013 various complementary tools and approaches: chemical extractions, optical microscopy, cathodoluminescence, Available online 12 September 2013 X-ray diffraction, Scanning Electron Microscopy, ElectronProbeMicro-Analysis,andmicro-Raman spectrometry. The primary assemblages are composed of analogs to willemite, hardystonite, zincite, wurtzite, petedunnite and Keywords: franklinite. Some of these phases are sensitive to alteration (e.g., deuteric processes during cooling and by Slag fi Weathering weathering) and, as a result, goslarite, smithsonite and hemimorphite have been identi ed as secondary products. Zn-phase stability In comparing these results to the geochemical conditions at each site in relation to mineralogical investigations, Melilites different steps of Zn-rich mineral destabilization could be identified. This procedure allows assessing potential Raman spectroscopy environmental impacts due to a release of metals that may contain slag. -

THE FRANKLIN STERLING MINERAL AREA by Helen A~ Biren, Brooklyn College " TRIP

'-_.-. E-l THE FRANKLIN STERLING MINERAL AREA by Helen A~ Biren, Brooklyn College " TRIP, . E Introduction The area which we shall visit is 'a limestone region lying in the New Jersey Highlands, which is part of the Reading Prong. It extends in a northeasterly direction ac~os5 the northern part of the state. The rocks are Precamqrian "crystal,lines" with narrow,beltsof in . folded and infaul ted Paleozoic. sedimentary rocks. Major 10ngi.::tr,~9;nal faults slice the fold structures,so that the area has been ,described as a series of fault blcicks e~iendingfr6m south of tbe Sterling Mine to Big Island, N. Y. ", ", For. many years the Franklin Limeston~iyielded enough zinc .to make 'New Jersey a, leading producer of this commo~!~ty.~)',Mining has steadily de creased in thi'sarea, and in '1955 thefrankl.inMine ~as shut dm.W1 perman :eDtl y, so .that mineral specimens are4eri ve({:ma~~l y ,from surfqce dumps and quarries. Some twenty million tons of ore were remQved from Franklin before it was shut down. Prior to mining, the ore outcropped in two synclinal folds com pletely within the limestone, which pitched to the northeast at an angle .. _" ,of about 250 with the horizontal. In these two horseshoe shaped bodies "Were developed the Franklin and the Ste,r,Ung M~nes. This zinc ore :h,,: unique in its lack of sulfides and lead mir,tera~~:, and in the occurrence 'of frankliniteand zincite as substantia~~ore m~nerals. : :: The limestone has produced nearly 200 species of minerals, some 33 of which were first found ip,Fr(inklin,and .about 30 of which have never been found el$emere.