3. the Great Watershed: 1750–1790

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen U Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80°

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Voyage UNDER THE Midnight Sun Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen u Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80° 80° Raudfjorden Nordaustlandet Woodfjorden Smeerenburg Monaco Glacier The Arctic’s 79° 79° 79° Kongsfjorden Svalbard King’s Glacier Archipelago Ny-Ålesund Spitsbergen Longyearbyen Canada 78° 78° 78° i Greenland tic C rcle rc Sea Camp Millar A U.S. North Pole Russia Bellsund Calypsobyen Svalbard Archipelago Norway Copenhagen Burgerbukta 77° 77° 77° Cruise Itinerary Denmark Air Routing Samarin Glacier Hornsund Barents Sea June 20 to 30, 2022 4° 8° Spitsbergen12° u Samarin16° Glacier20° u Calypsobyen24° 76° 28° 32° 36° 76° Voyage across the Arctic Circle on this unique 11-day Monaco Glacier u Smeerenburg u Ny-Ålesund itinerary featuring a seven-night cruise round trip Copenhagen 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada aboard the Five-Star Le Boréal. Visit during the most 2 Arrive in Copenhagen, Denmark enchanting season, when the region is bathed in the magical 3 Copenhagen/Fly to Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, light of the Midnight Sun. Cruise the shores of secluded Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago/Embark Le Boréal 4 Hornsund for Burgerbukta/Samarin Glacier Spitsbergen—the jewel of Norway’s rarely visited Svalbard 5 Bellsund for Calypsobyen/Camp Millar archipelago enjoy expert-led Zodiac excursions through 6 Cruising the Arctic Ice Pack sandstone mountain ranges, verdant tundra and awe-inspiring 7 MåkeØyane/Woodfjorden/Monaco Glacier ice formations. See glaciers calve in luminous blues and search 8 Raudfjorden for Smeerenburg for Arctic wildlife, including the “King of the Arctic,” the 9 Ny-Ålesund/Kongsfjorden for King’s Glacier polar bear, whales, walruses and Svalbard reindeer. -

Nyhetsbrev 323 Äldre Rara Böcker 19:E Mars 2019

ANTIKVARIAT MATS REHNSTRÖM antikvariat mats rehnström nyhetsbrev 323 äldre rara böcker 19:enyhetsbrev mars 2019 305 moderniteter 25 september 2017 Jakobsgatan 27 B | Box 16394 | 103 27 Stockholm | tel 08-411 92 24 | fax 08-411 94 61 Jakobsgatan 27 nb | e-post:Box 16394 [email protected] | 103 27 Stockholm | www.matsrehnstroem.se | tel 08-411 92 24 | fax 08-411 94 61 e-post: ö[email protected] torsdagar |15.00–18.30 www.matsrehnstroem.se öppet torsdagar 15.00–18.30 fter ett långt uppehåll kommer här årets första nyhetsbrev. Det innehåller som Hej! vanligt 25 nykatalogiserade poster, denna gång med äldre rara böcker från 1539 E till 1865. Den äldsta boken är en tidig upplaga av Johannes Boemus berömda och mångaetta gånger nyhetsbrev omtryckta kulturhistoria innehåller 25 Omnium nykatalogiserade gentium mores, böcker leges och & ritussmåskrifter. Från samma sekelfrån är förstaantikvariatets upplagan avdelning av Thietmar moderniteter. av Merseburgs Denna medeltida gång är tyska temat krönika, konst och vilken tillhörtkonsthantverk Gustav III. Frånfrån nästaperioden århundrade 1885–1965 finns med den start engelska i opponenternas översättningen utställ - avD Johannes Schefferus The history of Lapland tryckt 1674 och 1700-talet är rikt ningskatalog Vid Seinens strand. Yngst är ett vernissagekort från Moderna museet. representerat med verk av bland andra Anders Berch, Anders Chydenius, Jonas Flera kataloger dokumenterar konst och konsthantverk som visades på olika stora Hallenberg, Abraham Sahlstedt och Eric Tuneld samt av den vackra dukatupplagan svenska och internationella utställningar, som Stockholm, 1909, Malmö 1914, Göte- av Sveriges rikes lag tryckt 1780. Atterbom och Tegnér i fina band tillhör urvalet från borg 1923, Paris 1925, Chicago 1933 och Paris igen 1937. -

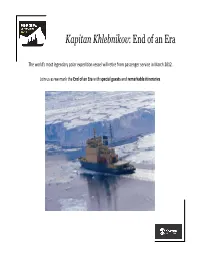

End of an Eraagent

Kapitan Khlebnikov: End of an Era The world’s most legendary polar expedition vessel will retire from passenger service in March 2012. Join us as we mark the End of an Era with special guests and remarkable itineraries. 2 Only 112 people will participate in any one of these historic voyages. As a former guest you can save 5% off the published price of these remarkable expeditions, and be one of the very few who will be able to say—I was on the Khlebnikov at the End of an Era. The legendary icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov will retire as an expedition vessel in March 2012, returning to escort duty for ships sailing the Northeast Passage. As Quark's flagship, the vessel has garnered more polar firsts than any other passenger ship. Under the command of Captain Petr Golikov, Khlebnikov circumnavigated the Antarctic continent, twice. The ship was the platform for the first tourism exploration of the Dry Valleys. The icebreaker has transited the Northwest Passage more than any other expedition ship. Adventurers aboard Khlebnikov were the first commercial travelers to witness a total eclipse of the sun from the isolation of the Davis Sea in Antarctica. In 2004, the special attributes of Kapitan Khlebnikov made it possible to visit an Emperor Penguin rookery in the Weddell Sea that had not been visited for 40 years. 3 End of an Era at a Glance Itineraries Start End Special Guests Northwest Passage: West to East July 18, 2010 August 5, 2010 Andrew Lambert, author of The Gates of Hell: Sir John Franklin’s Tragic Quest for the Northwest Passage. -

The Lore of the Stars, for Amateur Campfire Sages

obscure. Various claims have been made about Babylonian innovations and the similarity between the Greek zodiac and the stories, dating from the third millennium BCE, of Gilgamesh, a legendary Sumerian hero who encountered animals and characters similar to those of the zodiac. Some of the Babylonian constellations may have been popularized in the Greek world through the conquest of The Lore of the Stars, Alexander in the fourth century BCE. Alexander himself sent captured Babylonian texts back For Amateur Campfire Sages to Greece for his tutor Aristotle to interpret. Even earlier than this, Babylonian astronomy by Anders Hove would have been familiar to the Persians, who July 2002 occupied Greece several centuries before Alexander’s day. Although we may properly credit the Greeks with completing the Babylonian work, it is clear that the Babylonians did develop some of the symbols and constellations later adopted by the Greeks for their zodiac. Contrary to the story of the star-counter in Le Petit Prince, there aren’t unnumerable stars Cuneiform tablets using symbols similar to in the night sky, at least so far as we can see those used later for constellations may have with our own eyes. Only about a thousand are some relationship to astronomy, or they may visible. Almost all have names or Greek letter not. Far more tantalizing are the various designations as part of constellations that any- cuneiform tablets outlining astronomical one can learn to recognize. observations used by the Babylonians for Modern astronomers have divided the sky tracking the moon and developing a calendar. into 88 constellations, many of them fictitious— One of these is the MUL.APIN, which describes that is, they cover sky area, but contain no vis- the stars along the paths of the moon and ible stars. -

Magnetic North: Artists and the Arctic Circle

Magnetic north Artists And the Arctic circle On view May 28, 2014 through August 29, 2014 Magnetic North is organized by The Arctic Circle in association with The Farm, Inc. The exhibition is sponsored by the 1285 Avenue of the Americas Art Gallery, in partnership with Jones Lang LaSalle, as a community based public service. IN MEMORY OF TERRY ADKINS (1953–2014) 2013 Arctic Circle Expedition Sarah Anne Johnson Circling the Arctic, 2011 Magnetic North How do people imagine the landscapes they find themselves in? How does the land shape the imaginations of people who dwell in it? How does desire itself, the desire to comprehend, shape knowledge? —Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams he Arctic Circle is a non-profit expeditionary residency program that brings together international groups of artists, writers, composers, architects, scientists, and educators. For Tseveral weeks each year, participants voyage into the open seas and fjords of the Svalbard archipelago aboard a specially equipped sailing vessel. The voyagers live and work together, aiding one another in the daily challenges of conducting research and creating new work based on their experiences. The residency is both a journey of discovery and a laboratory for the convergence of ideas and disciplines. Magnetic North comprises a selection of works by more than twenty visual and sound artists from the 2009–2012 expeditions. The exhibition encompasses a wide range of artistic practices, including photography, video, sound recordings, performance documentation, painting, sculpture, and kinetic and interactive installations. Taken together, the works of art offer unique and diverse perspectives on a part of the world rarely seen by others, conveying the desire to comprehend and interpret a largely uninhabitable and unknowable place. -

Kapitan Khlebnikov

kapitan khlebnikov Expeditions that Mark the End of an Era 1991-2012 01 End of an Era 22 Circumnavigation of the Arctic 03 End of an Era at a Glance 24 Northeast Passage: Siberia and the Russian Arctic 04 Kapitan Khlebnikov 26 Greenland Semi-circunavigation: Special Guests 06 The Final Frontier 10 Northwest Passage: Arctic Passage: West to East 28 Amundsen’s Route to Asia 12 Tanquary Fjord: Western Ross Sea Centennial Voyage: Ellesmere Island 30 Farewell to the Emperors 14 Ellesmere Island and of Antarctica Greenland: The High Arctic 32 Antarctica’s Far East – 16 Emperor Penguins: The Farewell Voyage: Saluting Snow Hill Island Safari the 100th Anniversary of the Australasia Antarctic Expedition. 18 The Weddell Sea and South Georgia: Celebrating the 34 Dates and Rates Heroes of Endurance 35 Inclusions 20 Epic Antarctica via the Terms and Conditions of Sale Phantom Coast and 36 the Ross Sea Only 112 people will participate in any one of these historic voyages. end of an era Join us as we mark the End of an Era with special guests and remarkable itineraries. The legendary icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov will retire transited the Northwest Passage more than any other as an expedition vessel in March 2012, returning to expedition ship. Adventurers aboard Khlebnikov were the duty as an escort ship in the Russian Arctic. As Quark’s first commercial travelers to witness a total eclipse of the flagship, the vessel has garnered more polar firsts than sun from the isolation of the Davis Sea in Antarctica. In any other passenger ship. Under the command of Captain 2004, the special attributes of Kapitan Khlebnikov made it Petr Golikov, Khlebnikov circumnavigated the Antarctic possible to visit an Emperor Penguin rookery in the Weddell continent, twice. -

Arctic Saga: Exploring Spitsbergen Via the Faroes and Jan Mayen Three

SPITSBERGEN, THE FAROES & JAN MAYEN SPITSBERGEN, GREENLAND & ICELAND Exploring the Fair Isle coastline; an encounter with Svalbard Reindeer; capturing the scenery. A Zodiac cruise with a view. Arctic Ocean GREENLAND SVALBARD Longyearbyen Bellsund Longyearbyen Hornsund Greenland Sea Arctic Saga: Barents GREENLAND Sea Three Arctic Islands: SVALBARD Jan Mayen FROM Exploring Spitsbergen via OSLO Norwegian Sea Spitsbergen, Greenland and Iceland SOUTHBOUND the Faroes and Jan Mayen Scoresby Atlantic Ocean A Sund RCT TO IC C OSLO Departing from Aberdeen, Scotland, the Arctic Saga voyage visits four remote IRCL Named one of the 50 Tours of a Lifetime by National Geographic Traveler, E Milne Ittoqqortoormiit Arctic islands. Sail through the North Atlantic to Fair Isle, famous for its bird Faroe Islands NORWAY this voyage offers the best of the eastern Arctic in one voyage. You start in Land observatory, followed by two days exploring the Viking and Norse sites on Shetland Spitsbergen, Norway, then sail south to Greenland to explore the world’s Denmark Islands Strait the Faroe Islands. Then it’s onto the world’s northernmost volcanic island, Atlantic Ocean Oslo largest fjord system and end in Iceland. There’s something for everyone: CLE Orkney C CIR ARCTI Jan Mayen. The last two days of your 14-day voyage are spent exploring Islands Fair Isle polar bears, walrus, muskoxen, local culture, ancient Thule settlements, Aberdeen Spitsbergen, always on the lookout for polar bears. hikes along the glacial moraine and tundra, and more. Reykjavik ICELAND Nature is the tour guide: Sea, ice, and weather conditions will determine your trip itinerary. Embrace the unexpected. -

Hacquebord, Louwrens; Veluwenkamp, Jan Willem

University of Groningen Het topje van de ijsberg Boschman, Nienke; Hacquebord, Louwrens; Veluwenkamp, Jan Willem IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Boschman, N., Hacquebord, L., & Veluwenkamp, J. W. (editors) (2005). Het topje van de ijsberg: 35 jaar Arctisch centrum (1970-2005). (Volume 2 redactie) Barkhuis Publishing. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 04-10-2021 Twenty five years of multi-disciplinary research into the17th century whaling settlements in Spitsbergen L. -

Franskundervisningen I Sverige Fram Till 1807

120. Carl Holm, Fridtjuv llerr, och folkhögskolan 1969: 121. Gustaf Sivg.~rd, Ur Växjö stifts folkundervisningskrönika 122. Lennart Tegborg, Folkskolans sekularisering 1895-1909 ÅRSBÖCKER I SVENSK UNDERVISNINGSHISTORIA 1970: 123. Uno Träff, Bidrag till Villstads skol- och kulturhistoria 124. At~gust l Sr!acsson, Ur Vittinge skolkrönika 148 1971: 125. Lennart Bobman (mg.), Ett landsortsläroverk Studier kring Vi5by Gymnasium 1821-1971 126. Berättelser om de Allmänna Svenska Läraremötena 1852, 1854 och 1863 1972: 127. Elof Lindälv, Om fynden på vinden i Majornas växelunder• visningsskola 129. Två studier i den svenska flickskolans historia: G1mhild Kyle, Elisabet Hammar Svensk flickskola under l 800-talet. Gunnar H errström, Frå• gor rörande högre sko!utbildning för flickor vid 1928 års riksdag 1973: 129. 'IXIi/helm Sjöstrand, Freedom and Equality as fundamental Educational Principles in Western Democracy. from John Franskundervisningen Locke to Edm\md Burke 130 Thor Nordin, Växchmdervisningens allmänna utveckling och i Sverige dess utformning i Sveri ~ e till omkring 1830. 1974: 131. Comenius' självbiografi 132. Yngwe Löwegren, Naturaliesamlingar och naturhistorisk un dervisning vid läroverken fram till 1807 1975: 133. Henrik Elmgren, Trivialskolan i Jönköping 1649-1820 134. Elisabeth Dahr, Jönköpings flickskolor 1976: 135. Sven Askeberg, Pedagogisk reformverksamhet. Ett bidrag U odervisningssituationer och lärare till den svenska skolpolitikens historia 1810-1825 136. Klasslärarutbildningen i Linköping 1843-1968. 137. Sigurd Astrand, Reallinjens uppkomst och utveckling fram till 1878 1977. 138. Högre allmänna läroverket för flickor i Göteborg 1929-66. Kjellbergska gymnasiet 1966-72 139. lngar Bratt, Engelskundervisningens framväxt i Sverige. Tiden före 1850 140. Thorbjörn Lengborn, En studie i Ellen Keys pedagogiska tän• o-. kande främst med utgångspunkt fr1n "Barnets lhhundrade". -

Sätra Brunn, Minnesstenar & Målningar

KONST I SALA KOMMUN utgiven av AVLIDNA SALAKONSTNÄRERS SÄLLSKAP 2021 Sätra Brunn, minnesstenar & målningar Sätra Brunn, minnesstenar & målningar Text på minnesstenen: TILL HÅGKOMST AV BISKOP ANDERS KALSENIUS DE SJUKES VÄLGÖRARE I slingan: STENEN • RESTES • VID • SÄTRA • BRUNNS • 200 • ÅRS • FEST • MIDSOMMAREN • 1900 • DÅ • S • E • HENSCHEN • VAR • INTENDENT • OCH • E • L • HENSCHEN • KAMRER • • FHDEL• Vet någon vad sista bokstavskombinationen FHDEL betyder? FH skulle kunna stå för Folke Henchen, men DEL? Konstnär Formgiven av Folke Henschen (1881-1977), huggen av Carl Gustaf Eriksson, Sala Titel Minnessten tillägnad biskop Anders Kalsenius År Invigd midsommardagen 1900 Teknik Huggen sten Placering Sätra Brunn KONST I SALA KOMMUN utgiven av AVLIDNA SALAKONSTNÄRERS SÄLLSKAP 2021 Sätra Brunn, minnesstenar & målningar Wikipedia 2020-01-26: Andreas (Anders) Kalsenius, född 1 november 1688 i Söderbärkes prästgård i Dalarna, död 24 december 1750 i Västerås, var en svensk biskop av Västerås stift, överhovpredikant, pastor primarius, donator och teolog. Andreas Kalsenius föräldrar var prosten och kyrkoherden Olof Kalsenius och Anna Rudbeck, dotter till biskopen Nils Rudbeckius. Vid nio års ålder sändes Kalsenius till universitetet i Uppsala, där han till en början idkade sina studier under ledning av ett par äldre kamrater, båda blivande biskopar, nämligen halvbrodern Nils Barchius och Andreas Olavi Rhyzelius. Promoverad till filosofie magister 1713 och prästvigd 1716, kallades han sistnämnda år till huspredikant hos riksrådet greve Gustaf Cronhjelm och befordrades till pastor vid Dalregementet samt bevistade såsom sådan kampanjen i Norge 1718. Från nämnda kår sökte och erhöll han 1720 transport såsom andre pastor vid livdrabanterna och utnämndes 1722 till extra ordinarie hovpredikant. Den personliga beröring som han genom det sistnämnda kallet kom med kung Fredrik I, påskyndade hans befordringar. -

Under En Mycket Lång Period I Den Teologiska Forskningen Har Frågan

GUDSTJÄNSTEN OCH REFORMATIONEN AV TEOL. DOKTOR GUSTAF TÖRN VALL, HÄLLESTAD1 nder en mycket lång period i den teologiska forskningen har frågan Uom gudstjänsten och reformationen knappast varit något problem. På teologiskt håll har man ofta ansett de gudstjänstliga frågorna såsom en bisak i jämförelse med reformationens nyskapelse i dogmatiskt och etiskt hänseende. De stora teologiska läroböckerna syssla med de centrala tros frågorna men ägna föga uppmärksamhet åt gudstjänsten. Detta avspeglas i ämnesrubriker sådana som Rechtfertigung und Versöhnung, das Verkehr des Christen mit Gott, Neubau der Sittlichkeit. Frågan angående guds tjänsten, dess väsen och förhållande till de centrala trosfrågorna framstod knappast som något problem, den var till sin egentliga karaktär något självklart och berördes föga av den teologiska forskningens framsteg. Hur man på detta håll såg på saken, kommer t. ex. till synes i Achelis’ defini tion av liturgikens begrepp. Den är, säger han, läran om de fasta kult- former, vari kyrkans enhetlighet yttrar sig. Man frestas sålunda här lätt till den slutsatsen, att det egentligen icke var reformationen, som var liturgiskt ointresserad utan snarare den evangeliska teologien i sitt tidi gare skede. På liturgiskt håll åter kom man snart nog att inta en negativ hållning till reformationen. Hos Luther t. ex. fann eller menade sig den enbart liturgi- historiskt intresserade finna en föga givande produktion, varför han sökte sig till andra källor för det liturgiska vetandet. Småningom godtogs det som en allmänt erkänd halvsanning, att Luther var liturgiskt ointresserad och att hans teologiska intresse icke rörde sig om något annat än rätt- färdiggörelsen genom tron. Ja, stundom kom domen över reformationens liturgiska insats att falla mycket hård. -

The Naturalist's Journals of Gilbert White: Exploring the Roots of Accounting for Biodiversity and Extinction Accounting

This is a repository copy of The Naturalist's Journals of Gilbert White: exploring the roots of accounting for biodiversity and extinction accounting. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/158543/ Version: Published Version Article: Atkins, J. orcid.org/0000-0001-8727-0019 and Maroun, W. (2020) The Naturalist's Journals of Gilbert White: exploring the roots of accounting for biodiversity and extinction accounting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. ISSN 0951-3574 https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2016-2450 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/0951-3574.htm Naturalist’s Journals Roots of The of accounting for Gilbert White: exploring the roots biodiversity of accounting for biodiversity and extinction accounting Jill Atkins Received 12 March 2016 Revised 17 January 2019 Sheffield University Management School, The University of Sheffield, 17 January 2020 Sheffield, UK, and 12 March 2020 Warren Maroun Accepted 17 March 2020 School of Accountancy, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa Abstract Purpose – This paper explores the historical roots of accounting for biodiversity and extinction accounting by analysing the 18th-century Naturalist’s Journals of Gilbert White and interpreting them as biodiversity accounts produced by an interested party.