The More Than Entertaining Greene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

Africa: La Herencia De Livingstone En a Burnt-Out Case, De Graham Greene Y El Sueño Del Celta, De Mario Vargas Llosa

ISSN: 0213-1854 'Civilizar' Africa: La herencia de Livingstone en A Burnt-Out Case, de Graham Greene y El sueño del celta, de Mario Vargas Llosa (‘Civilizing’ Africa: Livingstone’s Inheritance in A Burnt-Out Case, by Graham Greene and El sueño del celta, by Mario Vargas Llosa) BEATRIZ VALVERDE JIMÉNEZ [email protected] Universidad Loyola Andalucía Fecha de recepción: 8 de mayo de 2015 Fecha de aceptación: 1 de julio de 2015 Resumen: En este artículo usamos el concepto de „semiosfera‟ desarrollado por el estudioso ruso-estonio Juri Lotman para examinar las relaciones entre las comunidades nativas y las europeas en el Congo belga creadas por Graham Greene en A Burnt-Out Case y por Mario Vargas Llosa en El sueño del celta. Con este análisis tratamos de probar que aunque ambos autores denuncian con sus obras las terribles consecuencias de la colonización europea para los africanos, las comunidades nativas son descritas desde un punto de vista occidental y paternalista. Palabras clave: Congo. Colonización. Lotman. Semiosfera. Europeos. Africanos. Greene. Vargas Llosa. Abstract: In this article the concept of „semiosphere‟, developed by the Russian-Estonian scholar Juri Lotman, is used to examine the relationship between the African and the European communities in the Congo portrayed by Graham Greene in A Burnt-Out Case and by Mario Vargas Llosa in El sueño del celta. With this analysis I will prove that even though both authors denounce the terrible consequences of the European colonization had for the African people, the native communities in the novels are still depicted from a western paternalistic perspective. -

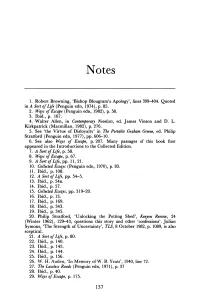

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

The Third Man"

"THE THIRD MAN" by Graham Greene HIGH ANGLE - FULL SHOT - CITY OF VIENNA The title VIENNA SUPERIMPOSED FADES OUT - commentary commences. COMMENTATOR I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its - MED. SHOT - STATUE OF A VIOLINIST There is snow on it. COMMENTATOR Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm... MED. SHOT - ROW OF STONE STATUES ornamenting the top of a building. In the b.g. the top of a stone archway. They are snow-sprinkled. COMMENTATOR Constantinople suited... MED. SHOT - SNOW-COVERED STATUE Trees in b.g. COMMENTATOR me better. I really got to know it in the... CLOSE SHOT - TWO MEN talking in the street. COMMENTATOR - classic period of the black... CLOSEUP - SUITCASE opens toward camera, revealing contents consisting of tins of food, shoes, etc. The hands of a man come in from f.g. to take something out. COMMENTATOR - market. We'd run anything... CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE standing side by side in the street. The person CL running hands through a pair of silk stockings. COMMENTATOR - if people wanted it enough. CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE A woman's hands CL wearing a wedding ring - a man's hands CR holding in RH two small cartons - hands them over to her in exchange for some notes which she hands him. COMMENTATOR - and had the money to pay. CLOSE SHOT - FIVE WRIST WATCHES on a man's wrist from which the coat sleeve is turned back. COMMENTATOR Of course a situation like that - LONG SHOT - CAPSIZED SHIP in shallow water with a drowned body floating on the water CR of it. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Andrew Martin Is an Author, Journalist and Broadcaster. His Previous Books with Profile Are Underground, Overground and Belles and Whistles

ANDREW MARTIN is an author, journalist and broadcaster. His previous books with Profile are Underground, Overground and Belles and Whistles. He has written for the Guardian, Evening Standard, Independent on Sunday, Daily Telegraph and New Statesman, amongst many others. His ‘Jim Stringer’ series of novels based around railways is published by Faber. His latest novel, Soot, is set in late eighteenth-century York. Praise for Night Trains ‘You do not have to be a trainspotter to enjoy this book. It is social history, a kind of epitaph to a way of travel that seems to be lost, at least in Europe.’ Spectator ‘A delightful book … charmingly combines Martin’s own travels, as he recreates journeys on famous trains such as the Orient Express, with a serious, occasionally geeky, history of those elegant wagons lits of the past … Even if you’re not into the detail of rail gauges, this book is the perfect companion as you wait for the 8.10 from Hove.’ Observer ‘Excellent … Mr Martin paints a vivid picture of this world on rails … he proves a witty companion who wears his knowledge lightly’ Country Life ‘Andrew Martin has cornered the train market. He is the Bard of the Buffer, the Balladeer of the Blue Train, the Laureate of Lost Property … I picked up Night Trains knowing that I would be entertained, but also in the hope that his many years of experience would teach me how to sleep on a sleeper … Andrew Martin is the best sort of travel writer: inquisitive, knowledgeable, lively, congenial. He is also very funny, while never letting the humour drive reality, rather than vice versa. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

The Destructors Graham Greene

The Destructors Graham Greene Online Information For the online version of BookRags' The Destructors Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-destructors/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Henry Graham Greene Was Born on October 2, 1904 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire

Henry Graham Greene was born on October 2, 1904 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. His father Charles Henry was headmaster of the private school Graham attended. The fourth of six children, Greene was very shy and sensitive. He disliked sports and was often truant from school in order to read adventure stories by authors such as Rider Haggard and Ballantyne. These novels had a deep influence on him and helped to shape his writing style. Greene was educated at Berkhamstead School and Balliol College, Oxford. He had a natural talent for writing, worked for the Times of London and published lots of poems, stories, articles and reviews. In 1927 he married Vivien Dayrell-Browning. After the collapse of their marriage he had several relationships. During World War II Greene worked for the Foreign Office in London. Greene died in Vevey, Switzerland, on April 3, 1991. Graham Greene is an English novelist, short-story writer and journalist, whose novels treat moral issues in the context of political settings. Greene is one of the most read novelist of the 20th-century, an excellent storyteller. Adventure and suspense are constant elements in his novels and many of his books have been made into successful films. Greene was a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature several times, but he never received the award. The Quiet American is set in Vietnam 1952, during the end of the French occupation and start of the American involvement. Thomas Fowler, a foreign correspondent for a newspaper in London, who is living there starts feeling comfortable at his new location, although he has to report stories of the war between the French army and the Communists in Vietnam.