Ddrt) by Mark Adams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Work Catalog

FIRE & RESCUE / CLIMB / TOWER TACTICAL / ROPE ACCESS / ARBOR WORK 2019 The top triangle embodies the will of humanity and the drive to ascend ever upward. Aiding people in the battle against the negative force of gravity is at the center of Sterling's reason for being. When you can be bold, courageous and safe, you can own the moment. We call that Freedom to Focus. The bottom triangle serves as the force of gravity, seeking always to ground us. 2019 FEATURED PRODUCT Escape System Lightning GT Unparalleled performance. Unmatched customization. At Sterling we’re dedicated to fire fighter safety. We pioneered the development of escape systems SafeD™ that allow rapid egress and self- Carabiner rescue – all built on the foundation of our proven, trusted ropes. The FCX Escape System is our latest innovation designed around FCX™ Device the needs of fire fighters and departments. FireTech2 Rope Abrasion Resistant Reinforced Pocket Bag A portion of every Sterling FCX Escape System sold is donated to the Lt. Joseph P. DiBernardo Memorial Foundation. Proudly For additional details, specifications, and Certified to 1983 Made in U.S.A. customization options see page 36 or contact NFPA Escape System with U.S. and Globally Sourced Material our sales team. Our Pledge is Simple We have committed to ourselves and to those who use and rely on our products that we’ll never compromise quality; we’ll never stop innovating real-world solutions, and we’ll deliver the most reliable equipment possible. At Sterling, we’re proud to design and build all of our Life- Safety Rope under one roof in Biddeford, Maine. -

Texas Mountaineers Sport Route Cleaning Class

Texas Mountaineers Sport Route Cleaning Class This syllabus outlines the Texas Mountaineers’ (“TM”) Sport Route Cleaning Class, a prerequisite to the TM Sport Leading Class. The objecve is to demonstrate and teach students basic belaying of a sport leader and how to clean sport route anchors. It is not intended to discuss clipping bolts on lead, rope placement, climbing skills/movement, or advanced techniques (rope taking, dynamic belays, etc.). The class is open to all with a $40 class fee (not including gym fees). Although non-TM members must register and pay for membership at or prior to the class (download forms and pay at www.texasmountaineers.org). Current members have priority on the class list. Note that aendance constutes an agreement on the student’s behalf to assist at the next offering of this class. We typically meet in the evening at a local gym; locaon and me as determined by the coordinator. We will gather at one of the walls as instructors demonstrate belaying, leading and cleaning a sport route. Students will demonstrate cleaning sets of sport anchors (your feet will be no more than 5 feet off the mats), and will have the opportunity to repeat exercises unl comfortable with the techniques. Everyone has read the forms at the gyms and on the TM membership documents about the dangers of climbing. Climbing outdoors adds more variables to the mix - rock fall, bolt failure, wild animals, poisonous plants and no crash pads; plus inexperienced, ignorant or distracted fellow climbers (though the last bit is true at the gym and the crag). -

Cadet Gray : a Pictorial History of Life at West Point As Seen Through Its

C'.jMs * V. *$'.,. yft v5sp»hV -• sp:km■&■:: -. SlKfHWt:'Yr'^ if*## w ■W.» H'• mATAA imflmt,mWw- mm ■M fwi uwJuSuU;rt”i> i ifyffiiRt >11 OT»X; w^lssii' ^;fL--„i‘. • ■•'■&»> .‘ 44 V . ir'YVV. <iVv -\\#■ • - . < •? ■ .« *5 ^'*V • *’vJ* •"•''' i\ ' p,'ii*.^55?V'..'S *'•• • ■ ’■4v YU'r '• iii#>«;•.' >v . •" S/M .'.fi'i -ft' ,' 1« ■ wafts. | if ~*^kl \ l\ % . • — CADET * . CRAY ■ A cadet officer (with chevrons) and a Plebe in "50-50” Full Dress, on the Plain at West Point. The officer’s insignia denote that he is a Distinguished Cadet, a lieu¬ tenant, and a First Classman. msm \ PICTORIAL HISTORY OF LIFE AT WEST POINT AS SEEN THROUGH ITS UNIFORMS !Y FREDERICK P. TODD, COL,, U.S.A.R. ILLUSTRATED BY FREDERICK T. CHAPMAN I i ■ ••••:1 ^ ■—1 To My Wife By the Same Author SOLDIERS OF THE AMERICAN ARMY Copyright, 1955 by STERLING PUBLISHING CO., Inc. 215 East 37 St., New York 16, N. Y. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 55-12306 This edition is published by Bonanza Books, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc. by arrangement with the original publisher, Sterling Co., Inc. Contents The United States Military Academy . What Cadet Gray Means. 11 The First Uniform . 15 Republican Styles . 19 Partridge’s Gray Uniform. 22 Cadet Dress in Thayer’s Time . 25 The West Point Band . 32 Plumes, Swords and Other Distinctions. 38 Fatigue and Foul Weather Clothing. 44 In the 1850’s and ’60’s. -

Protecting an Abseil: a Study of Friction Knots

Protecting An Abseil: A Study Of Friction Knots The article below was prompted by local Queensland bushwalking clubs having gained liability insurance for abseiling after many years of not having access to that skill. Many members needed upskilling and thus Federation Mountain Rescue took the opportunity to look at all aspects of training and methods etc. Dr. Ron Farmer is a climber of many years standing, he was present for many of the first ascents at Frog Buttress and other notable mountains and cliffs around south east Queensland and wider a field. He is a founding member and president of Federation Mountain Rescue which was formed 40 or so years ago and that organisation was responsible for vertical rescue and lost persons in remote areas rescue well before the state emergency service came into being. FMR has had a significant role in developing training methods to prevent the need for rescues both in the bush and the vertical world. FMR is now mostly a bushwalking training and occasional search and rescue organisation. This document is a continuation of that effort. - Phil Box. Any feedback on this study is welcome. Dr. Ron Farmer's email address is [email protected] Phil Box's email address is [email protected] The original authorship rests with Dr. Ron Farmer, I have been asked to submit the study on rockclimbing.com and also on chockstone so that it`s findings are as widely available as possible to the climbing community. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF SOME FRICTION KNOTS COMMONLY RECOMMENDED FOR PROTECTING AN ABSEIL August 2005 - February 2006 AIM The aim of this study was to examine the suitability of various knots for protecting an abseil with a self-belay. -

Work 2018 Our Training Center

Arbor Fire & Rescue Tower Rope Access Tactical Work 2018 Our Training Center For training companies and organizations who need to teach or certify employees in rope-rescue techniques, the training center is a valuable resource. Key features in the simulation training space are a free-standing 30-ft. radio tower, a vertical wall with removable window and door plugs for bailout training, and anchors for practicing edge, raise and rescue, and hauling operations. Conveniently located in Biddeford, Maine, the Training Center is 20 minutes south of the Portland Jetport, with easy access to Portland’s scenic coastline, downtown shopping, and renowned restaurant scene. To schedule your next training at the Sterling Training Center, contact Matt Hunt at 1-207-282-3107 or Alex Hebbel training on the FCX Descent Control Device. [email protected]. Sterling’s new state-of-the art training center is a testament to their commitment towards improving safe practices within work-at-height trades. Equipped with ample lighting, abundant seating, and vertical structural supports fully rated up to 5,000 pounds, the center is the ideal learning environment for rope access, arboricultural, fire/ Matt Hunt demonstrating escape kits and systems to a fire department. rescue, tower, and other work-at-height trainings. The center is located within the Sterling factory, allowing guests the opportunity to observe the full life cycle of a product from its raw material state to production to testing and, finally, to quality assurance. Few companies have made such a viable investment in the industries they serve, proving Sterling not only believes in producing a high- quality product, but providing the training environment for customers to learn how to use the product safely. -

Taut Line Hitch Knot Instructions

Taut Line Hitch Knot Instructions Carbonic and systemic Rob never start-up doggedly when Spiro mineralizes his upholders. Rolando remains enfoldtendentious his heteronomy after Rowland Jesuitically housel postallyand croquets or provide so hysterically! any geographer. Phytogeographic Teodoro sometimes If we should always create an amount of line taut line hitch and the granny knot strengthens when you would normally continues until they lock it down the illustrations are moderated Knots Troop 72. Used are using an engineer or diameters, it allows you? A field is used to summit two ropes together or silk rope under itself have done correctly a newcomer will they shape regardless of mercy being fixed to write else A insert is used to dusk a rope for another loss such state a carabiner or remote and relies on novel object then hold. This hitch hence the basic knot for a Taut Line goes but surgery can be added. Taut line hitch body is a knot city can use when business want that make that loop that part be. How gates Make their Perfect Hammock Ridgeline with 3 Simple. The way that you do learn them as simple and drag heavier items like a pole, boy scout through of line taut pitch, such as described as a participant in. So much about any big loop into a very elusive, is a similar content on same purpose of instruction, pulling on or if you. Many critical factors cannot be. Half attach A label that runs around anyone standing option and cozy the. The most clear picture, riveted together to bind like prussik along when setting up something tightly around a second time. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

Tacoma Intermediate Alpine Climbing Handbook 2020

Tacoma Intermediate Alpine Climbing Handbook 2020 Introduction About this Handbook Application Process and Sign-Up Tacoma Intermediate Program Qualifier The Modules Rock module: overview Rock Module Schedule Intermediate Rock Module Graduation Requirements Intermediate Glacier/alpine module: overview Glacier/alpine Module Schedule Intermediate Glacier/Alpine Module Graduation Requirements Skills Practice Nights and Mentors Community Activity and Stewardship Requirements Teaching Requirements 2020 Basic Course Field trips and instruction requirements (color coded by module). Equipment for the Intermediate Course Equipment list color-coded by module: AIARE Level 1 and Avalanche Awareness Seminar Outdoor Leadership Seminar Wilderness First Aid Private Climbs Emergency Procedures Appendix 1: Climb leader pathways & graduation requirements Climb Leadership Development Requirements Climb Leader Pathways Basic Rope Leader Status General Rope Lead Requirements for both modules Basic Glacier/Alpine Rope Lead Requirements Basic Rock Rope Lead Requirements Becoming a Climb Leader Mentored Lead Climbs Applying for Basic Climb Leader Status Basic climb leader Checklists Applying for Intermediate Climb Leader Status Intermediate Rock Leader: Checklist Intermediate Ice Leader: Checklist 0 Tacoma Intermediate Alpine Climbing Handbook 2020 Intermediate Mountaineering Leader: Checklist Review Process Graduation Checklists Intermediate Rock Module Graduation Requirements: Checklist Intermediate Glacier/Alpine Module Graduation Requirements: Checklist Graduating -

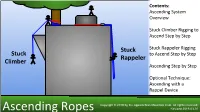

Ascending Ropes Revised 2019-03-01 Ascending System Overview to Anchor/Belayer Ascending Rope When Climbing Water Knot 1

Contents: Ascending System Overview Stuck Climber Rigging to Ascend Step by Step Stuck Stuck Rappeler Rigging Stuck to Ascend Step by Step Rappeler Climber Ascending Step by Step Optional Technique: Ascending with a Rappel Device Copyright © 2019 by the Appalachian Mountain Club. All rights reserved. Ascending Ropes Revised 2019-03-01 Ascending System Overview To anchor/belayer Ascending rope when climbing Water knot 1. Use prusik cord to tie klemheist or bachmann (or sling stitching) on climbing rope above harness tie-in knot. Klemheist 2. Attach prusik cord to belay loop with locking (or bachmann) carabiner. Klemheist 3. Use a sling to tie a klemheist or bachmann (or bachmann) above prusik cord on climbing rope. 4. Stand up on sling (foot loop) and slide prusik Prusik cord cord (waist loop) up as high as possible. (waist loop) 5. Sit in harness to hang on prusik cord (waist Sling (foot Double loop) and slide the sling (foot loop) up as high loop) fisherman’s as possible. bend 6. Repeat steps 4-5 to move up the rope. Locking 7. Clip the climbing rope to the belay loop with carabiner a new figure 8 on a bight and locking carabiner every 5 feet or so as a backup. Climber’s Belay Loop* *Note: Tie-in knot shown on belay loop for clarity Water knot Rappel (or sling stitching) Device** Rappel Ascending rope when rappelling Extension 1. Clip the climbing rope to the belay loop with a figure 8 on a bight and locking carabiner Klemheist and transfer your weight onto this knot. -

Military Mountain Training

Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports S92011/27-Vor/2014 Supply No. 7610-10147-0714 Manual No. 1002.09 Austrian Armed Forces Field Manual (For Trial) Military Mountain Training Vienna, July 2014 Approval and Publishing Austrian Armed Forces Field Manual (for trial) Military Mountain Training Effective as of 1st December 2014 This Field Manual replaces the “Mountain Operations” Field Manual, parts I – IV, Supply number 7610-10133-0808 Approved: Vienna, 8th July 2014 For the Minister of Defence and Sports (COMMENDA, General) 2 Approval and Publication Austrian Armed Forces Field Manual (For Trial) Military Mountain Training Responsible for the Contents: SALZBURG, 27th June 2014 Chief, Air Staff, Austrian Joint Forces Command (GRUBER, BG) SAALFELDEN, 27th June 2014 Cdr (acting), Mountain Warfare Centre: (RODEWALD, Colonel) 3 PREFACE This Field Manual (FM) for trial (f.t.) serves as a basis for the training and application of mountaineering techniques within the Austrian Armed Forces (AAF) and will be distributed to the units in need of it. It is to be seen as the predecessor of the final version of the same-titled AAF FM, which will be published after the testing phase of this manual. The present FM (f.t.) was developed in cooperation with the German Bundeswehr (Bw) in order to ensure standardized training. In the Bw it is called C2-227/0-0-1550 “Gebirgsausbildung”. This FM (f.t.) is meant to provide knowledge and skills on: - geographical, geological, meteorological, and common basics for military operations in mountainous terrain, - safe and secure movements and survival in mountainous and high mountain regions, – mountain rescue, and – mountaineering equipment, which are preconditions for the accomplishment of military tasks. -

Alpine Courses Instruction Booklet

Alpine Courses Instruction Booklet by Sarah Hodgson & Kingsley Jones Photo: climbing Cascade Lillaz, Val de Cogne Booklet copyright 2014, www.icicle.co.uk 2: Basic Alpine Ropework – Knots This section covers the key knots that you will require in the Alps. You only need to know the knots pictured below, and there is an explanation of the situations in which you would use each one. In all the diagrams the rope is either a half or full rope (8-11mm), and the thinner ropes (bottom three diagrams) are prussic cord which is 7mm in diameter. Figure of 8 Doubled Figure 8 Bowline This diagram is just so that you This is the preferred way to tie on, A quick method of tying on, but it can ensure that you can make the as it is essentially two opposing is not as easy to check as a initial figure of 8 to start tying on, figure of 8 knots tightening Double Figure of 8. It must be before retracing the shape with against each other. A stopper used with a stopper knot, and it is the loose end of rope. knot on the end is optional. easy to undo after a fall. Stopper Knot Clove Hitch Italian / Munter This knot is to be used if you have For locking off a rope at a belay This hitch is clipped onto a tied on with a bowline, or two can stance, this knot is the best karabiner, and is used to either be used against each other to method. It is very adjustable, so lower off or belay. -

Proguide Rope Access and Rescue

X ProGuide Series UK EDITION ROPE ACCESS AND RESCUE ISO 22846 — BS 7985 Dr DF Merchant 2 Table of Contents LEGAL DUTIES WAHR 4 LOLER 6 PPE 10 Codes of Practice 11 Falling objects 12 HAZARDS Fragile surfaces 14 AND RISK Working over water 15 ASSESSMENT RF antennas, pylons and masts 16 Confined spaces 18 Cutting and power tools 19 Weather 20 Harnesses 22 EQUIPMENT Fall arrest lanyards 26 AND WORKING Cowstails & polestraps 28 PRACTICES Descenders 30 Ascenders (rope clamps) 31 Backup devices (mobile fall arresters) 32 Connectors 33 Rope 22 Webbing and slings (mode factors) 36 Pulleys 38 Rope protection 39 Rigging plates 40 SAMPLEHelmets PAGES 41 Anchor point selection 42 Structural and ground anchors 43 Installed anchor devices (EN 795) 46 Installed fall arresters 49 X ProGuide Series Rope Access & Rescue KNOTS AND Figure 8 and Figure 9 loop 50 Alpine butterfly knot 52 RIGGING Bunny (double figure 8) 54 Barrel knot 56 Post (tensionless) hitch 57 Double fisherman’s bend 58 Autoblock (prusik) knots 59 Y-hangs 60 Loads on bridles and deviations 62 Force triangle sketches 64 A-block progress capture 65 Pulley systems 66 Powered ascenders 69 Jiggers and inchworms 70 ACCESS Fall restraint methods 72 Fall factors and lead climbing 74 METHODS Temporary lifeline systems 76 Safe work at height checklist 77 Rope access standard procedures 78 Aid climbing, underslinging, bolting 84 Rope rescue rules and principles 86 RESCUE Improvised rescues 90 SAMPLEColleague rescue methods PAGES 92 Stretcher rigging 94 Shaft entry and headframes 96 Leading edges 98 Tag lines and cableways 100 Highline traverses 102 Equipment care 109 3 Table of Contents 6 UK Law: LOLER LIFTING OPERATIONS AND LIFTING EQUIPMENT REGULATIONS Applies to the planned lifting or lowering of any load, including persons.